21 Years of 9/11

The end of the Cold War scrambled foreign policy every countries — and then 9/11 scrambled it again. But this remains the same.

Twenty One (21) years ago, the September 11 terrorist attacks shocked the world. “We are all American” became a global slogan of solidarity. Suddenly, the West’s post-Cold War invulnerability had been exposed as an illusion. Globalization, which had become the reigning paradigm and established Western economic dominance in the 1990s, turned out to have a dark side. 911 redefined the contours of U.S. foreign policy, and in general, foreign policy in every countries.

It has entered the history books as the beginning of something new, a new era perhaps, but in any case a time of change. The terrorist bombings in Madrid and London and elsewhere will also be remembered; but it is “9/11” that has become the catchphrase, almost like “August 1914.” The 9/11 attacks created upheaval for Muslims worldwide.

Successive U.S. administrations have attempted to debunk al-Qaeda’s anti-West narrative and improve relations with Muslims, but challenges continue. American Moslem to be 4th class, pariah, until today in America, regardless several prominent profile reach high ranking in Biden administration, Congress, and even in NYC.

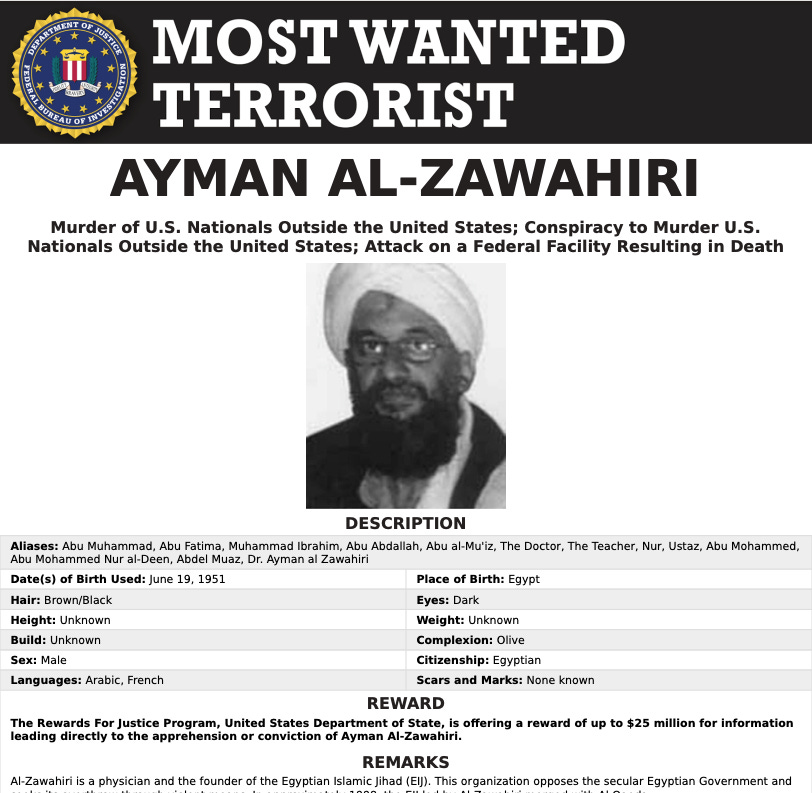

Every year, that day hits me like it just happened. As Asian-tanned (dark, accurately) man, in the days after 9/11, I never doubted this was my country, the biggest Moslem majority country in the world (220 million out of 274 million Indonesians are Moslem like me) and my home. Everything else felt meaningless, nothing felt safe from an extreme evil. Many, like me, were fundamentally shaped by that day. International Relations shaped again, like the moment of the Soviet Union's fall. A shock we slowly emerged from that moved to anger and then to turning on each other. This is the 1st year where evil has ebbed away. Bin Laden is long dead, Zawahiri died less than 100 days ago. Evil is always lurking in the shadows. It can strike with devastation and horror. Even on a sunny beautiful fall morning like it did on September 11, 2001. Or night of Bali Bombing Oct. 12 2002 .

President Joe Biden revealed that a U.S. drone strike killed al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri on July 31th.Zawahiri was critical to al-Qaeda’s survival in the decade since the 2011 killing of its previous leader, Osama bin Laden. He held the movement together through his force of personality and strategic vision, which was to allow the various al-Qaeda franchises to pursue their local and regional agendas and have

But was it really a war that started on September 11, 2001? Not all are happy about this American notion. During the heyday of Irish terrorism in the UK, successive British governments went out of their way not to concede to the IRA the notion that a war was being waged. “War” would have meant acceptance of the terrorists as legitimate enemies, in a sense as equals in a bloody contest for which there are accepted rules of engagement.

Muslims were among the thousands of victims of the 9/11 attacks perpetrated by hijackers from Egypt, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Yet, arguably not since the 1979 Iran hostage crisis had American Muslims experienced the kind of intense scrutiny and distrust that was unleashed after the attacks.

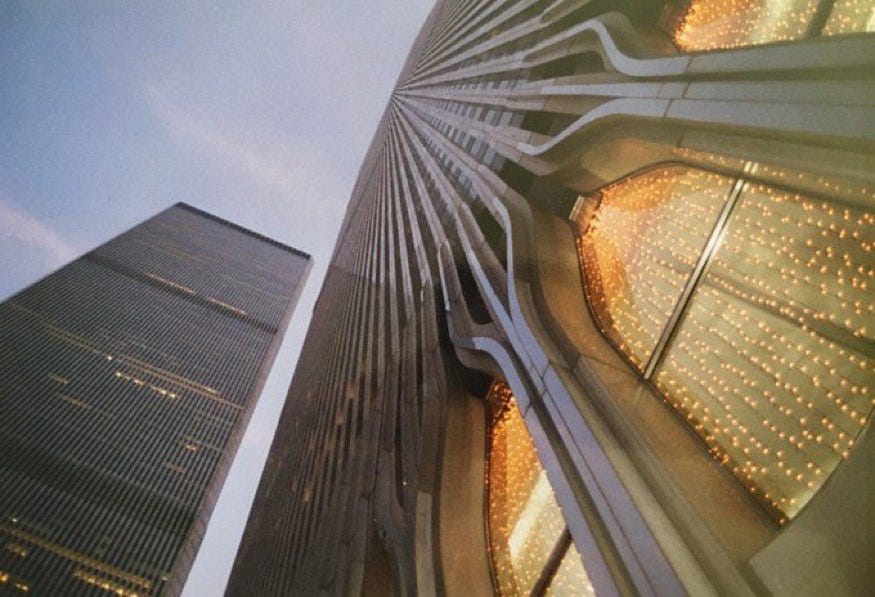

(NYE 2000. Still Twin Tower)

This is neither a correct description nor a useful terminology for terrorist acts, which are more correctly described as criminal. By calling them war – and naming an opponent, usually al-Qaeda and its leader, Osama bin Laden – the United States government has justified domestic changes that, before the 9/11 attacks, would have been unacceptable in any free country.

Most of these changes were embodied in the so-called “USA Patriot Act.” Though some of the changes simply involved administrative regulations, the Patriot Act’s overall effect was to erode the great pillars of liberty, such as habeas corpus , the right to recourse to an independent court whenever the state deprives an individual of his freedom. From an early date, the prison camp at Guantánamo Bay in Cuba became the symbol of something unheard of: the arrest without trial of “illegal combatants” who are deprived of all human rights.

The world now wonders how many more of these non-human humans are there in how many places. For everyone else, a kind of state of emergency was proclaimed that has allowed state interference in essential civil rights. Controls at borders have become an ordeal for many, and police persecution now burdens quite a few. A climate of fear has made life hard for anyone who looks suspicious or acts suspiciously, notably for Muslims.

The 9/11 attacks created upheaval for Muslims worldwide. Successive U.S. administrations have attempted to debunk al-Qaeda’s anti-West narrative and improve relations with Muslims, but challenges continue twenty years later.

Muslims were among the thousands of victims of the 9/11 attacks perpetrated by hijackers from Egypt, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Yet, arguably not since the 1979 Iran hostage crisis had American Muslims experienced the kind of intense scrutiny and distrust that was unleashed after the attacks.

Physical assault, emotional abuse, and discrimination, alongside an often-politicized conversation about “real Islam,” have created a toxic environment for American Muslims ever since. Although most Americans did not contribute to the idea that there is something inherently bad about Islam, there were enough voices of hate, deliberate misinformation, and genuine misunderstandings to create a powerful message: Muslims are not to be trusted. This created multilayered societal unease that changed the life many American Muslims (who composed 1.1 percent of the population in 2017, according to Pew Research Center) knew prior to the attacks.

Since the attacks, divisions in American society have deepened amid changes wrought by the technology and media revolution, the weaponization of misinformation, and foreign policy choices. Muslims, like other minorities, have become caught up in the sometimes-bitter national conversation about history, race, religion, ethnicity, and heritage.

But there are still some important areas of progress. New connections and coalitions have taken off in the last twenty years. Amid a rise in hate crimes against minorities, Americanongovernmental organizations (NGOs), community groups, and other civic organizations have found allies and built new relationships. Civil society and religious leaders have polished their advocacy, while philanthropists are finally turning their attention to issues of hate and extremism.

American Muslims have found new agency and organizations to use art, culture, and policy as vehicles to repair societies and build understanding.

The importance of listening to diverse civil society voices, engaging with local and national leaders, and creating new bridges has activated many Muslim and non-Muslim Americans. More should be done, but there are improvements in the way non-Muslims talk about Islam today, as well as in the dialogue about ensuring inclusive societies.

However, anti-Muslim political rhetoric and policies as well as far-right ideology in the United States have grown through the financing, organization, and networking of those who do not want an inclusive country.

Such restrictions on freedom did not meet with much public opposition when they were adopted. On the contrary, by and large it was the critics, not the supporters, of these measures who found themselves in trouble. In Britain, where Prime Minister Tony Blair supported the US attitude entirely, the government introduced similar measures and even offered a new theory. Blair was the first to argue that security is the first freedom. In other words, liberty is not the right of individuals to define their own lives, but the right of the state to restrict individual freedom in the name of a security that only the state can define. This is the beginning of a new authoritarianism.

More than two decades after the attacks, it is difficult to overstate their consequences for the West and the wider world. A violent non-state actor determined the international agenda to an extraordinary degree. While the hegemony of the West, led by the United States, remained unquestioned, the unipolar moment of the 1990s seemed to be coming to a close, and US foreign policy would be fundamentally reshaped by the “global war on terror.”

In the context of the time, it was no surprise that the US-led invasion of Afghanistan met with overwhelming international support. The 9/11 attacks could not go unanswered, and it was the Taliban who had provided a haven for al-Qaeda to plan, organize, and launch the operation.

The United States sought to debunk the al-Qaeda narrative that the West is at war with Islam in part through global outreach to Muslims, both via governments and at the community level. At the same time, al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden and his recruiters across the globe used U.S. foreign policy choices as “proof” of American hostility toward.

The U.S.-led wars in Afghanistan (& persuade Afghanistan to help the U.S., with very complicated situation) and Iraq helped feed al-Qaeda’s narrative, as did other activities related to the U.S.-declared global war on terrorism. The widely distributed images of Iraqi prisoners abused at Abu Ghraib, as well as drone strikes and the ongoing controversies surrounding the Guantanamo Bay prison, served to ignite anger and outrage. The ability of terrorist organizations such as the self-proclaimed Islamic State and others to use these images to recruit members can’t be overstated. The U.S.did send aid – roughly $40 billion over the past decade. Even amid massive flood nowadays in Pakistan, U.S. commitment not only relief fund but also agreement about weapon. But the bulk of these resources went to the Pakistani military. And, while US policymakers consider the amount of aid to be generous compensation for Pakistan’s help, Pakistani officials maintain that the economic losses from the spread of terrorism in the country are far higher. Calculated the losses at up to 7% of the country’s GDP, or $12 billion a year – six times the amount of annual US aid inflows.

Worse still has been the impact on Pakistan’s ethnic make-up. Fragments of the country’s Pashtun population organized themselves to carry out operations against Pakistani military and soft civilian targets. One group, Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) – succeeded in attacking a number of military installations, including the army’s headquarters in Rawalpindi, and briefly occupied the district of Swat, only 60 miles from Islamabad, the capital.

The TTP also established an Islamist government in South Waziristan, one of the tribal agencies on Pakistan’s border with Afghanistan. Pakistan’s military later succeeded in expelling the TTP from both areas, but not without a great many casualties.

The Taliban reacted to these defeats by launching terrorist attacks in many urban centers, particularly in Punjab, killing more than 15,000 people over the last six years. The people of Punjab, the country’s largest province – accounting for 56% of the country’s population and 60% of its GDP – regard the Pashtun attacks as a form of inter-ethnic violence.

Such violence is much in evidence in Karachi, where tens of thousands of people displaced by the ongoing warfare in Pakistan’s tribal areas have fled. During most of this summer, well-armed gangs representing the Muhajir community (the descendants of refugees from India who arrived in and around 1947, the year of Pakistan’s birth) and the Pashtuns have waged battles across the city. An estimated 400 people have been killed in this fighting.

So, should Pakistan have refused to participate in the war on terror? No matter how it had reacted to the US request for help in eliminating the threat posed to its security by Al Qaeda and the Taliban, this fight would have arrived in Pakistan.

But the war could have been conducted in a way that minimized the cost for Pakistan. There could have been greater emphasis on negotiating a settlement with those in the Taliban who were prepared to work with the governments of Afghanistan and Pakistan. The measure of the chosen strategy’s failure is that how to reach such a negotiated settlement remains a relevant question to this day.

Physical assault, emotional abuse, and discrimination, alongside an often-politicized conversation about “real Islam,” have created a toxic environment for American Muslims ever since. Although most Americans did not contribute to the idea that there is something inherently bad about Islam, there were enough voices of hate, deliberate misinformation, and genuine misunderstandings to create a powerful message: Muslims are not to be trusted. This created multilayered societal unease that changed the life many American Muslims (who composed 1.1 percent of the population in 2017, according to Pew Research Center) knew prior to the attack.

Since the attacks, divisions in American society have deepened amid changes wrought by the technology and media revolution, the weaponization of misinformation, and foreign policy choices. Muslims, like other minorities, have become caught up in the sometimes-bitter national conversation about history, race, religion, ethnicity, and heritage.

But there are still some important areas of progress. New connections and coalitions have taken off in the last twenty years. Amid a rise in hate crimes against minorities, American nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), community groups, and other civic organizations have found allies and built new relationships. Civil society and religious leaders have polished their advocacy, while philanthropists are finally turning their attention to issues of hate and extremism.

American Muslims have found new agency and organizations to use art, culture, and policy as vehicles to repair societies and build understanding. For instance, the Pillars Fund, a pioneering, grant-giving organization, focuses on amplifying the leadership and talents of American Muslims. The importance of listening to diverse civil society voices, engaging with local and national leaders, and creating new bridges has activated many Muslim and non-Muslim Americans. More should be done, but there are improvements in the way non-Muslims talk about Islam today, as well as in the dialogue about ensuring inclusive societies.

The United States sought to debunk the al-Qaeda narrative that the West is at war with Islam in part through global outreach to Muslims, both via governments and at the community level. At the same time, al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden and his recruiters across the globe used U.S. foreign policy choices as “proof” of American hostility toward Muslims.

The U.S.-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq helped feed al-Qaeda’s narrative, as did other activities related to the U.S.-declared global war on terrorism. The widely distributed images of Iraqi prisoners abused at Abu Ghraib, as well as drone strikes and the ongoing controversies surrounding the Guantanamo Bay prison, served to ignite anger and outrage. The ability of terrorist organizations such as the self-proclaimed Islamic State and others to use these images to recruit members can’t be overstated.

Despite this, the United States had to find a way to build new connections with communities, find common purpose, and build networks of like-minded thinkers that were united in the interest of protecting young people from being lured into a terrorist group that claimed to represent “real Muslims.” Critically, Muslims all over the world were eager to push back against terrorist organizations trying to radicalize and recruit their youth.

U.S. officials created new coalitions of civil society partners such as Generation Change*, a global network of youth “change-makers” with thirty international chapters that advanced local initiatives to reject the appeal of extremist narratives.

Perhaps one of the biggest lessons is that the United States needs to bring far more resources and attention to confront the challenge, right down to the community level at home and abroad. Societies need a multilayered approach that connects with kids, parents, teachers, faith leaders, community activists, civil society leaders, local leaders, and others. Programs of action should be scaled and happen at every level to influence the multiple factors that affect one’s identity and sense of belonging. Such programs vary between communities even within a nation.

Because diminishing the ideological appeal of violent extremism is a vital U.S. interest, dramatic change is required in mindset, focus, and funding. It requires the whole of society to take part; it requires everyone.