"Bloody Money" in Sports From Abramovich until the Qatari: Try to refused a money, but abruptly wants Oil & Gas after Russia invasion

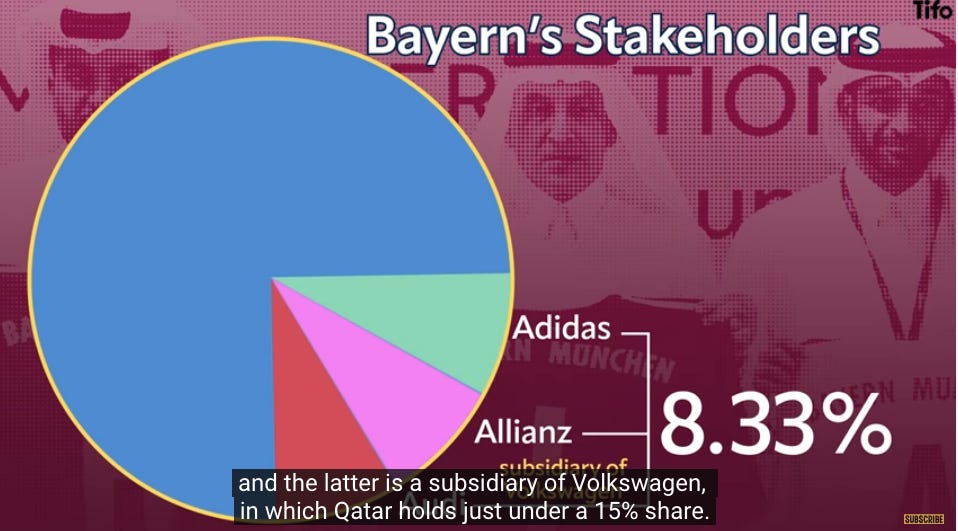

Further illustrate scepticism about sport management’s capacity to cope with the world’s new reality, consider Russia’s Gazprom both for Schalke 04 and Zenit St. Petersburg. Or Roman Abramovich to Chelsea FC. Or how Qatar try, via very complicated way to discuss with Pep Guardiola, ex Al Ahli FC Qatar club, Pep play on 2003-2005 (when Pep still Head Coach for FC Bayern) is look desperate how Qatar really wants to be FC Bayern’s sponsor. Qatar, with another way about Volkswagen shareholder (Qatar owns 15% of VW shares—-and AUDI, under VW group, is FC Bayern sponsor) make a smooth pitching to pursue deal with FC Bayern. Then in 2018 (Pep no longer in Bayern) Qatar and FC Bayern agreed to cooperation until 2023.

First, on Gazprom issue. Its origins are as a Russian state-owned oil and gas producer, which in the early nineties was privatised under the programme of Glasnost and Perestroika (Rosner, 2006).

For a while, oil, coal, nickel, and gas markets in the former Soviet Union were liberalised though once Vladimir Putin became president of Russia, Gazprom (as it is now known) was essentially renationalised and now serves the needs of the state. Subsequently, Gazprom became a sponsor of the UEFA Champions League (and the German Bundesliga’s FC Schalke 04); the corporation’s president Alexander Dyukov even sits on UEFA’s Executive Committee. Gazprom really “special” for Putin not only very mammouth company, but also the fact Gazprom Headquarter is Putin’s hometown: St Petersburg

Unlike other sponsors – such as McDonalds, Coca Cola or Mastercard – Gazprom’s relationship with UEFA is neither a B2C (business-to-consumer) nor a B2B (business-to-business) deal. Instead, it is best characterised as a G2G (government-to-government) deal, enabled by the diplomatic and networking opportunities that the Champions League matches.

To some, this could seem trivial; however, it needs to be set in the context of United States sanctions against Gazprom amid warnings from Washington that Germany’s dependence upon Russian gas constitutes a major strategic threat to European energy security-dependence. Nord Stream 2 opens in 2011, and Angela Merkel & Mark Rutte (Netherland) on the ceremony beside (on 2011) President Dmitry Medvedev. Such is the network of economic, political and strategic factors within which Gazprom’s sponsorships are embedded that the existing sport management literature (in this case, specifically in sponsorship) is ill-equipped to explain such contemporary developments amid Russia invasion to Ukraine (I write live blog this war, click here).

Abramovich, of course, very complicated stories. When he came to London, nearly same time when Alexander Litvinenko, defect from Russia (*he’s ex KGB/FSB agent) to UK. Then November 2005, Litvinenko died because poisoned (some Polonium on his blood). What happened in November 2005 at Chelsea FC? Roman success to get a 2 superstars in this time: Andriy Shevchenko (Captain for Ukraine National Football Team, from AC Milan Italy) and Michael Ballack (Captain for Germany/DFB Team, from FC Bayern), and both started to playing for Chelsea on August 2006 (after World Cup 2006 in Germany). Two countries (Germany & Ukraine) now to be “so called enemies” for Putin. 2006 Russia and Ukraine really warm relation. Until 2008 (Russia invaded Georgia), and more and more bad things until Russia - Ukraine war started February 24th 2022.

2 Days ago, UK desk of Wall Street Journal, reportage Abramovich & 2 person Ukraine negotiator get poisoned. A Karma? But Abramovich currently very fit. Then, currently (too), under massive sanction, Chelsea FC maybe get a special treatment, from “very Russia” (because Abramovich), now UK government try every way to make sure new owner of Chelsea FC is American. Even, a “mysterious-abruptly” to be contender of next potential owner is (linkage with) Bain Capital, U.S. investment firm.

Qatar is also complicated. The uneasy relationship between Bayern Munich's bosses and fans over the club's links with Qatar has worsened after an ill-tempered Annual General Metting (AGM). At the club's AGM (November 26, 2021), the rejection of a motion from Bayern member and lawyer Michael Ott to discuss ending Bayern's partnership with Qatar Airways (since 2018) prompted calls for club president Herbert Hainer's resignation and saw the atmosphere turn confrontational. Hainer, ex adidas CEO (*in Asia, adidas only represented by Japan and UEA; Qatar use NIKE, at least Japan qualified into World Cup 2022 in Qatar) confirmed the club would not end its sponsorship deal.

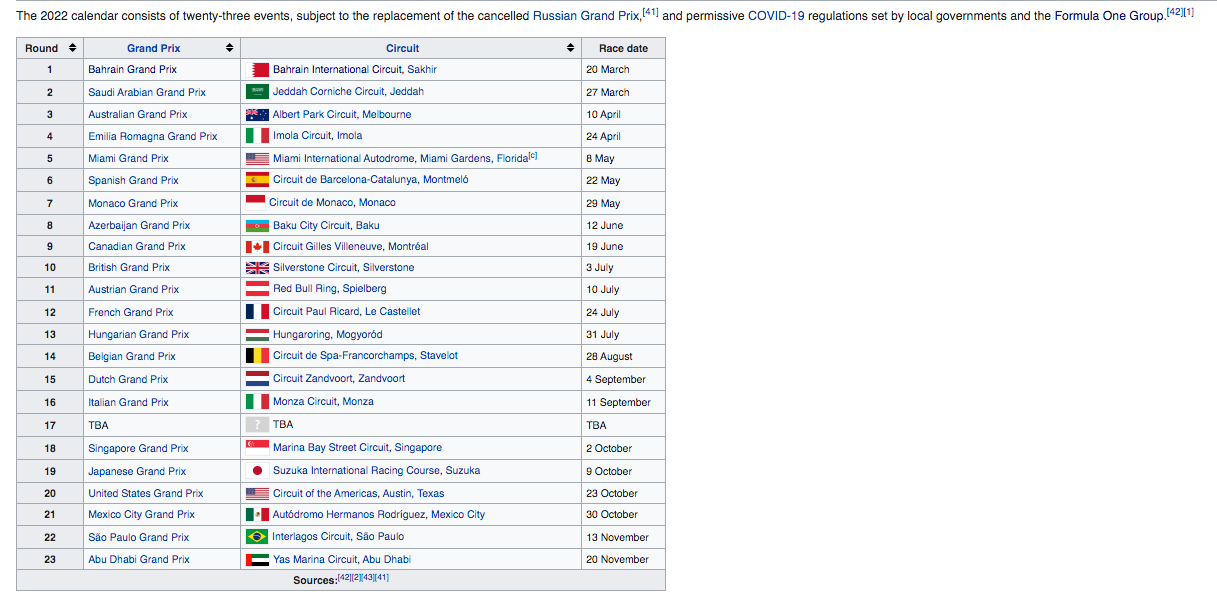

Ott has become the face of a sustained and determined movement to get Bayern to cut ties with Qatar over its record on human rights. With last weekend's Formula One Grand Prix in the Gulf state and the World Cup now less than a year away, the spotlight is intensifying.

"You can no longer be proud of successes when you know the burdens and compromises with which they were achieved," Ott told DW earlier this week. "If I know that this money comes from Qatar and is associated with serious human rights violations, if it is clearly blood money, then the successes associated with it are tarnished and, in my opinion, something to be ashamed of."

Though heated, the scenes at the Audi Dome were not the first time Bayern's recently ascended management team have come under pressure of late. In the game against Freiburg this month a huge banner was unfurled by supporters behind the goal at the Allianz Arena (see top picture).

"We'll wash anything clean for money," read the text, above depictions of Bayern CEO Oliver Kahn and club president Hainer putting blood-stained clothing labeled "Qatar" into a washing machine, surrounded by bank notes.

Though the new board members have had to deal with the continuing fallout of the coronavirus and player vaccinations, supporter unrest on Qatar seems to be a divisive issue.

Kahn responded to criticism by reiterating that the club have "clear criteria on which we align partnerships," while his predecessor Rummenigge has consistently claimed that such partnerships, and hosting of events, increase scrutiny on Qatar in an attempt to deflect from claims of sportswashing.

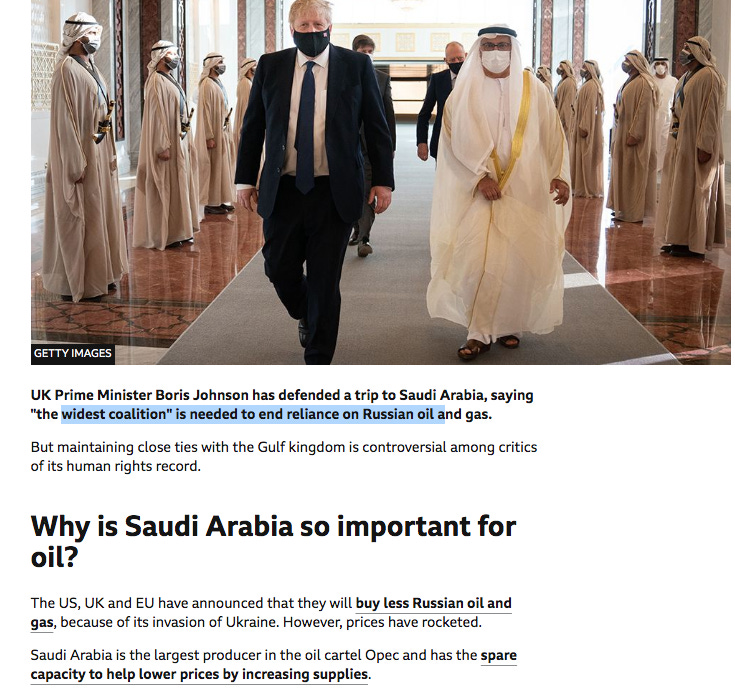

Now, with conundrum energy-security issue, and moral hazard to leave Russia alone and (another) moral hazard to no longer use Russia energy and mining, the awkward, Germany might wants …. Qatar again. And actually UK wants (oil and gas) Saudi again.

Human Rights organizations, and many Bayern members, take some issue with that. "We cannot completely sacrifice our values on the altar of success," added Ott.

=========

In observing sport during the first quarter of the twenty-first century, one can still see the contemporary intersection of utilitarianism and neoclassicism, that is of sport which is influenced by different ideologies and competing perspectives. For instance, during the early part of 2021, twelve European football clubs revealed proposals to break away from UEFA’s existing Champions League structure and its attendant system of governance by establishing a Super League (The Economist, 2021).

The clubs’ motives were underpinned by the principles of free-market capitalism, whereby profitability is the ultimate arbiter of an organisation’s operations, indeed its existence. Nevertheless, the proposal caused a huge outcry amongst Europeans, particularly fans, who were driven by a sense of community and identity, underpinned by notions of history and heritage, and resentment about the ideological dominance of North America and its sport. Nevertheless, in this episode were some significant stakeholders.

One of the clubs, Italy’s Internazionale of Milan, was then owned by a Chinese high street electrical retailer after long time ownership under Masimmo Moratti, a Italian oil-tycoon. Chelsea, was owned by Abramovich. In a further instance, Manchester City of England was owned by an Abu Dhabi state investment vehicle which had used the club as the basis for opening multiple franchises across countries, including India, China and Japan.

Rumours have circulated that the Super League itself was planning to use funding from Saudi Arabia to establish the league and award prize money to the participants. Elsewhere, the Chinese government has envisioned itself becoming the world’s largest domestic sport economy by 2025. Hence, the country has enacted policy and created a programme of investments that has embraced everything from event hosting and stadium construction to the acquisition of overseas sports assets and the development of new broadcasting services.

There is great resonance for sport in the twenty-first century among these questions. States, governments and related entities are engaged in using their geographies, resource endowments and politico-economic characteristics to build power and exert control within and out with sport. This means that the desire to win on the field is increasingly paralleled by a desire to win off it.

Equally, winning in sport and winning through sport is also connected. China’s government has stated that it wants the country to become a leading FIFA nation by 2050. Many observers have characterised this as an intention on China’s part to win the men’s World Cup, which is potentially beneficial to the nation in many ways. Sadly, meanwhile China really “king” on a lot sport, specific in football, China only qualified once time through to World Cup (2002, host Japan and South Korea). Even, China failed to qualify for WC 2022 in Qatar, a country who use at least 85% of Covid vaccination from (made in) China-vaccine (Sinovac).

However, the country’s vision, when framed in geopolitical terms, can be interpreted in a different way. For instance, Chinese corporations are an increasingly dominant presence in FIFA’s portfolio of sponsors. Indeed, the FIFA president has publicly acknowledged the financial stability that money from China has brought to the organisation. Strategically, this has created a resource-dependent relationship between FIFA and China, enabling the latter to exert a degree of power and control over the former. It seems likely that this will be used as the foundation for a future Chinese World Cup hosting bid and to promote the politico-economic benefits that the government in Beijing is seeking to derive from being a host. With Asia hosting in 2022 (Qatar) and North America in 2026 (USA, Canada & Mexico), that leaves the 2030 host opportunity to Africa, Europe and South America (not yet Asia again).

The domain of sport’s geopolitical economy is all-pervasive, encompassing sport at all levels and impacting policy, strategy, governance, marketing. Furthermore, on matters pertaining to, for example, transgender athletes, decolonisation and racism, analysing such phenomena in terms of geopolitical economy is important.

For instance, China has recently sought to suppress LGBTQ+ rights, in terms of event staging and event sponsorship, have significant consequences, especially for Western sponsors engaged in China, whilst promote brand values globally that emphasise a commitment to LGBTQ+ rights. It seems inevitable that some will point to, say, Saudi Arabia’s aspiration to become an established mega-event destination or Qatar’s ownership of multiple sport assets as embodying the essence of this paper’s central proposition.

However, China’s funding of community sports facilities in Africa or Great Britain’s spending on grassroots sport in other countries is manifestation of sport’s geopolitical economy. It is also important for readers to note that although one proposes here that geopolitical economy should displace neoclassicism and utilitarianism as the dominant paradigm in sport research, this does not negate the significance of management, governance, strategy, organisational behaviour, leadership and so forth. Sport as a geopolitical economy still requires good management. However, rather than being guided by neoclassical principles, the contention here is that managers exist within the environment of,and engage in activity driven by inter-related considerations of geography, politics and economics.

To illustrate, consider the influx of investment into the global sport industry from the Gulf region over the last two decades. Members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates) are all endowed with significant oil and gas deposits, which has conferred significant wealth upon them.

Bahrain not only enjoyed relation with F1 administrator (in past Bernie Ecclestone, now since January 2021 lead by Stefano Domenicali). Since 2004, Shakir Circuit Bahrain nearly to be opener season (or at least 2nd or the 3rd race, mostly amid contender: Adelaide GP and Sepang GP) every year, include this 2022 season.

Like Qatar, with human rights issue, and years ago a “nearly success” coup’d’etat in Bahrain, international public push F1 organization to banned Bahrain to be a F1 host, but failed.

Accordingly, we have seen considerable investments being made by these nations in sports infrastructure, event hosting, team formation and overseas sports assets (from horse racing and powerboat racing to cycle teams and football clubs). Other geographies that underpin and help explain some countries’ prominent roles in sport are Britain’s island status, colonial ambitions and the consequent impact this has had upon world sports, such as cricket and rugby; and Japan’s strategic position in the Pacific, which led to the United States’ influence upon the country and the resultant popularisation of baseball.

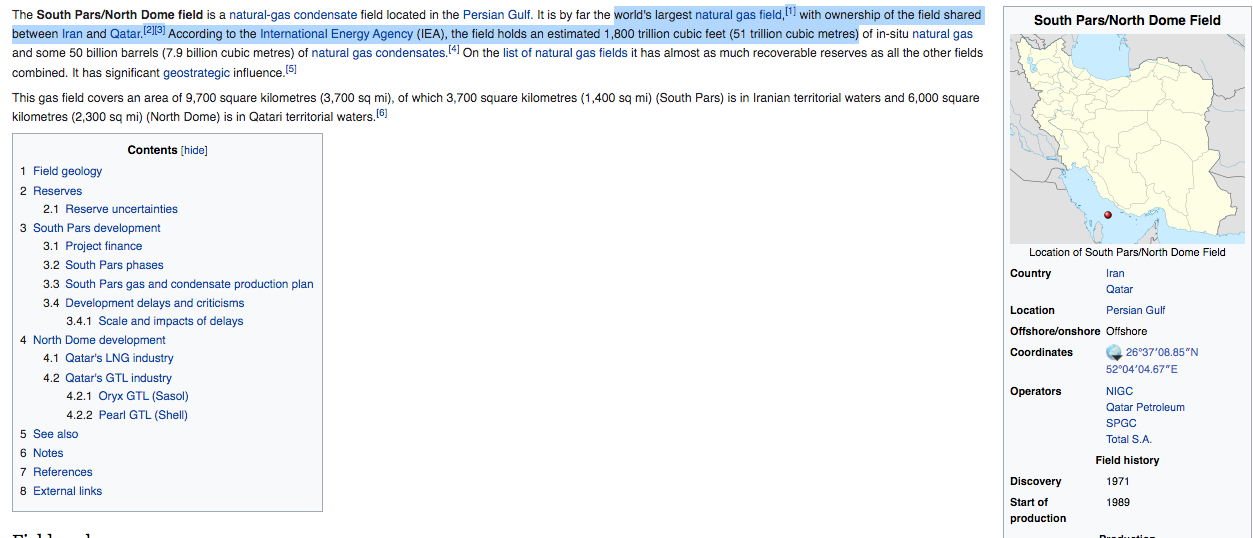

However, it is Qatar’s vulnerable geographic position and the way that the government in Doha has used sport as means by which to boost its profile, presence, legitimacy and security, whilst serving to diversify its economy away from oil and gas dependence that epitomise the significance of geography for this paper (as background and to fully understand this point, it is recommended that readers familiarise themselves with Qatar’s position on a map).

Perhaps the embodiment of twenty-first century networked sport, City Football Group now owns or licences its name to football clubs in a double-digit number of territories. At one level, this network is intended to enable the timely identification, acquisition, development and disposal of playing talent and other human resources. At another level, CFG’s network enables the organisation’s Abu Dhabi state owners to engage in geopolitical and economic relationships. In one instance, CFG acquired a franchise club in Chengdu, China, which served as the basis for enhancing the state airline’s (Etihad) presence in East Asia (where Chengdu Airport is an important transit hub for the airline).

At the same time, CFG’s ownership brings together organisations from China (China Media Capital) and the United States (Silver Lake) that have served to further the strategic interests of the organisation’s owners from the small Gulf State. In another instance, CFG acquired an Indian franchise club in Mumbai, not uncoincidentally the home of India’s film industry – commonly referred to as Bollywood at the same time as Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth fund (Mubadala) acquired a stake in a tech company, Reliance Jio, which is headquartered in Mumbai.

Almost simultaneously, Silver Lake also purchased a stake in Reliance Jio, creating a network of interconnected investments linking the sport, entertainment and the digital technology sectors, and the strategic interests of an oil and gas-dependent Gulf state, private equity investment from the United States, and investments drawn from opaque Chinese sources.

The race of sponsorship, at least before pandemic Covid began, really transparent amid several airline companies from Middle East plus Turkiye. Qatar Airways (Qatar), Etihad (UAE), Emirates (UAE), and Turkish Airline really aggressive to be sponsored a global name of football club. For example, Boca Junior with Qatar Airways, when the biggest rival, River Plate, with Turkish Airline. Or several years ago, when Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo still in the peak performance, Barcelona get Qatar Airways, when Real Madrid get Emirates. Currently in Premier league, Manchester City get a Etihad, when arsenal sponsored by Emirates.

Nevertheless, the politico-economic impacts a country’s team, club, league and event successes can have should not be underestimated; after all, the National Basketball Association, English Premier League and Ferrari Formula One team are all acknowledged as having soft power and nation branding effects for their respective countries.

However, in the way that countries envision sport, the policies and strategies they pursue, and the outcomes they seek broader, contemporary notions of national competitive advantage in sport need to be established. For instance, e-sports, countries, including South Korea and Denmark, have implemented state policies to establish themselves as global leaders in this fast-emerging industrial sector.

Similarly, Saudi Arabian government policy is currently focused upon positioning the country as a sport event destination, which is particularly manifesting itself in motorsport and combat sports. At least today, Saudi monarch have a Newcastle United, when UK government success to kick Saudi from Chelsea FC beauty contest, because UK government worried if Chelsea falls to Saudi ownership only repeated Abramovich case. Similarly, reports published by the English Premier League in conjunction with consulting business EY highlight the importance of the competitive advantage built through football. In this context, the following questions are proposed as the basis for stimulating contributions to the geopolitical economy. And the ugly truth, when UK banned another Saudi and or Middle East Tycoon to own EPL club (only Newcastle United get a permit, UK government use influence to mae sure candidate of new owner Chelsea isnt Saudis), UK government actually wants an oil and gas from Saudi.

With the world thus having changed significantly since the emergence of research and publication in sport management, academia needs to respond with some alacrity. The utilitarian and neoclassical foundations of studies in sport management are not dismissed here as now being outdated; indeed the extensive body of knowledge built over the last four decades will continue to form the basis for researchers and others to understand micro-level phenomena in sport. However, with the advent of a new geopolitical economy of sport, sport management needs to reposition, refocus, rename and move on from its European and North American origins.

This is not meant to imply that an Asian conception of sport will necessarily come to dominate the field in coming years. Jacksonville Jaguar NFLs (Shahid Khan, from Pakistan), Brooklyn Nets NBAs (Joe Tsai, co-founder Alibaba China), Sacramento Kings NBAs (Vivek Ranadive from Mumbai India), owned by Asian, and its only example in the U.S. Thanks for Hiroshi Yamauchi became the first Asian-born owner of an American sports franchise when Nintendo bought the Seattle Mariners in 1992.

Rather, one of this paper’s main takeaways is that global sport in its entirety is, to a greater or lesser extent, now impacted by the geopolitical economy – this is not about the disintegration of one country or ideology and the rise of another. However, it does necessitate that scholars, researchers and others in the field of sport should change how they see a discipline that has thus far broadly been framed as ‘sport management’. Issues and questions pertaining to the geopolitical economy of sport have been proposed in this paper, and one anticipates that further questions will emerge as a sport (and our understanding of it) develops in the second quarter of the twenty-first century. At the same time, in posing then answering such complicated questions.

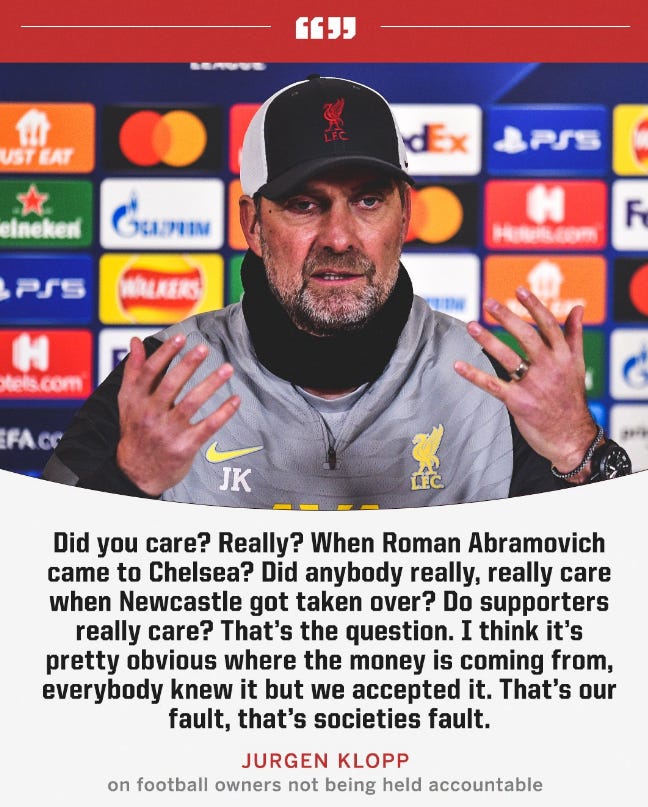

(*more bizzare context: Klopp in years to be a Coach for Borussia Dortmund, very struggle budget to facing *very adidas club* named FC Bayern (adidas have a shares in Bayern), then currently in Liverpool, with U.S. owner John W. Henry with US$ 3.6 Billion worth, and another / minority shareholder is LeBron James, the great Nike active-athlete currently. Liverpool actually Nike sponsored, but Klopp is adidas ambassador)

Whilst some people may feel threatened or disconcerted by the profound changes our sport community is now facing, one prefers to see this period as one of the most exciting in the field’s history. It allows the discipline to extend and move on from its origins and old certainties into new ways of seeing the world. Sport management – in neoclassical and utilitarian forms – is not dead although a new life is being breathed into our community and its work by a new geopolitical economy of sport.