During his first United Nations (UN) speech at the 77th UNGA, Chile’s President Gabriel Boric Font, 36 years old (youngest in UNGA this year), urged “not to normalize the permanent violations of Human Rights against the Palestinians, asserting international law & the resolutions that year after year this same assembly establishes” for Palestinian self-determination.” From Palestine to Brazil, Nigeria to Spain, Ireland to Chile, a global coalition has formed to demand the immediate decolonization of the Western Sahara — the last colony in Africa.

This follows another stand from the Chilean President last week as he “refused to receive the credentials of Israeli apartheid Ambassador due to the recent Israeli apartheid crimes in Gaza and West Bank, Chilean media reported. Nearly same minutes Boric’s speech in NYC-UN Headquarter (11 am ET—Sept 20th), in other continent, in Tel Aviv (7 pm local time), a new forensic analysis proves that an IDF / Israeli Defense Forces sniper could see that Shireen Abu Akleh was a AL Jazeera journalist before firing the bullet that killed her. Boric has supported Palestine throughout his political career.

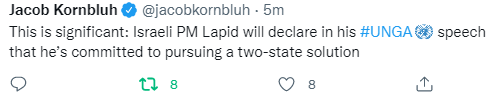

26 Hours after Boris’s speech, Israeli PM Yair Lapid will declare in his #UNGA speech that he’s committed to pursuing a two-state solution

Please not confused why Chilean is very supportive to Palestine (like Irish, Scottish). The Arab countries that have the highest Palestinian populations are Jordan and Syria. Chile has the largest Palestinian population outside of the Middle East. Palestinians in Chile (Arabic: فلسطينيو تشيلي) are believed to be the largest Palestinian community outside of the Arab world.[2] Estimates of the number of Palestinian descendants in Chile range from 450,000 to 500,000. They maintain good relations with the Jews, are reluctant to visit Israel and Palestine, but identify with their brethren in the territories.

The Club Palestino is one of the most prestigious social clubs in Santiago; it offers swimming, tennis, and dining facilities to its members. There is also a soccer football team, C.D. Palestino, whose uniform is in the traditional Palestinian colours red, green, and white, one and only Football Club using “PALESTINE” name outside Palestine. The team has been champion of the Chilean Primera División twice.[6] Also, some Chilean-Palestinian footballers like Roberto Bishara and Alexis Norambuena have played for the Palestine national football team. Other Chileans of Palestinian origin, such as Luis Antonio Jiménez, played international football for Chile and several foreign clubs.

Nadia Chahin, now 35, saw herself first and foremost as a citizen of Chile. Even if she supported the Palestinians fervently, that was mainly an emotional connection. Like many Chileans of Palestinian descent, she doesn’t speak Arabic. Her maternal grandparents arrived in Chile in 1920; her father’s family immigrated in 1948, but not as refugees. Everyone did well: Her father is a physician, her mother is a lawyer, and Chahin herself practices law.

When she was 22, she made what she says was an impulsive decision to visit the West Bank and meet the part of her family that had remained there. She arrived via the Allenby Bridge crossing from Jordan on her own. And there, for a few hours, she ceased to be a free Chilean citizen and became a Palestinian subject to abuse.

“I was very uptight. The girl at the border asked for my email password and entered it on her computer. I was left to wait on a chair in the corridor. No one spoke to me, other than a soldier who was supposedly looking after me. I was hysterical and felt very vulnerable. I had no idea what would happen to me. For 12 hours they let everyone else through, but I was left sitting on that chair. It was an awful experience. In the end they informed that I wasn’t allowed to enter Israel or the territories. They told me I would never get to the territories.”

Between 300,000 and half a million people with Palestinian roots live (happily) in a country with a population of 18 million. A local saying has it that in every small village in Chile you’ll find a priest, a policeman and a Palestinian. About 95 percent of the “Chilestinians” are Christians whose origins lie in the Jerusalem-area triangle of Bethlehem, Beit Jalla and Beir Sahour. Most of the families immigrated before the 1930s and with no connection to the creation of Israel. There are now more Palestinian Christians in Chile than within the areas controlled by the Palestinian Authority.

The main impulse for those early waves of emigration was the Ottoman conscription law. Christians were drafted at an early age and sent to the front, sometimes unarmed, to serve as cannon fodder in battles against other Christians, in the Balkan wars and in World War I. Since the Palestinians arrived in Chile with Ottoman papers, they were dubbed “Turks.” The epithet stuck even after 1918, when the papers they carried were from the British Mandate, and over the years, it became a derogatory term. On the other hand, the fact that they were Christians, like most Chileans, helped them integrate. In addition, the Middle East-like Chilean climate, despite its tendency to grayness, eased the immigrants’ longings for home.

At first, the Palestinians sold goods in the streets. They saved up until they were able to open small stores, sometimes next to Jewish merchants. Later, they became dominant in local textile manufacture and in the real estate business; today people of Palestinian descent control a hefty slice of Chilean banking, again alongside Jews.

It’s hard for an Israeli journalist not to juxtapose Chilestinians and Diaspora Jews, who sometimes outdo Israelis. The Chilestinians reminded most of the warm Jews I met in France. Their idealization of Israel and their anger at and fear of the Arabs are quite similar to the Chilestinians’ love for Palestine and their fury at Israel and its actions. Chilean expressed great interest in the fate of the Palestinians and was thinking about how they could help their distressed relatives. The Chilestinians, by contrast, were very serious and gloomy.

Some believe in a Palestinian state alongside Israel, set within the pre-1967 borders; others advocate a one-state solution. There are those who back BDS but are afraid to admit it out loud, for fear they will not be allowed to visit their relatives in the territories. Others are against BDS, but are also afraid to say so, for fear of angering members of their community.

Chile is the most economically successful and democratically stable country in South America today, and by now the Palestinians who live there are Chilean in every respect. It would be hard for them to integrate in Palestine. Arabic was lost to them a hundred years ago, and a course in the language offered this year by the Palestinian Club drew only a few dozen people from a vastly larger potential.

Another Palestinian decent, Jamila, the restaurant that’s named for her is an avocation. “Our aim is not only to sell food but to show that Palestine exists – the food is only an excuse. It’s a symbol of the homeland, of our identity. We inserted butterflies in the logo in the colors of the flag, because the butterfly is a symbol of freedom. I don’t want to get into politics, but Palestine needs to be free.”

She’s proud that when Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas visited Chile half a year ago, he asked for food from the restaurant to be sent to his hotel. “He said that he hadn’t eaten Palestinian food this good in 70 years,” she says, glowing. “He went to the Palestinian Club, saw all the flags of Palestine and said that he felt like he was in Palestine, not Chile.”

======

Boric —- as a dynamo in South America

=====

If former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva reclaims the post in this October’s election (as now seems likely), and if Colombia’s leftist presidential candidate, Gustavo Petro, wins in May, their victories would build on a wave that began with Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s victory in 2018. After AMLO came victories by Argentinian President Alberto Fernández in 2019, Bolivian President Luis Arce in 2020, and Peruvian President Pedro Castillo and Chilean President Gabriel Boric in 2021.

Many observers see a repeat of the “pink tide” that followed Hugo Chávez’s rise to power in Venezuela in 1999. Successive leftist victories then went to Chilean President Ricardo Lagos in 2000, Lula in 2002, Bolivian President Evo Morales in 2005, and Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa in 2006, among others.

To some, the current trend reflects necessary change in countries where inequality has become unbearable in the wake of the pandemic. But to others, the leftward shift should be seen as a significant threat to the region and to the United States, considering the extremism of some of the new leaders and the inroads that Russia and China have been making in Latin America.

In fact, the situation is more complicated than either of these views suggests. After the first pink tide, I noted that there were two Latin American lefts: one was modern, democratic, cosmopolitan, pro-market, and social democratic; the other was nationalistic, authoritarian, statist, populist, and anachronistic. Now, there are clearly three “lefts,” each with little in common with the others.

To be sure, all the leaders of the current wave identify as progressives, and the success of many is a response to poor management of the COVID-19 pandemic. Their programs all place a strong emphasis on populist social policies, and most have a discernible anti-American outlook on foreign policy and issues such as mining rights and inward investment.

But there are significant differences. The first of the three lefts includes the trio of dictatorships: Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. While these regimes seek to associate themselves with the rest of the Latin American left, and while other leftist regional leaders avoid criticizing them, they are fully in a category of their own. Since 2018, all the new leaders have been, or will be, democratically elected in countries that enjoy basic freedoms, market economies, and cordial relations with Washington, DC. Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela share none of these features.

Boric is a good example. Although his coalition has an uncompromising left wing that includes the Communist Party, the Mapuche indigenous movement, and several radical members of a Constituent Assembly, Boric seems to be following in the footsteps of predecessors like Lagos and Michelle Bachelet (who forged what former Chilean Minister of State Carlos Ominami called the “new Chilean way”).

Boric, Lula, and even Fernández are arguably closer to the center than to the far left, because they emerged from multi-round electoral systems in which victory requires reaching beyond one’s political base. The cases of AMLO, Petro, Castillo, and Arce are different. AMLO makes a point of governing only for his base, and Petro has made clear that he would govern for the eco-activist left (which perhaps explains the recent decline in his approval ratings).

Similarly, Arce remains close and loyal to the populist Morales, his former boss and predecessor as Bolivian president. And while Castillo has spent more time warding off recurrent impeachment attempts than anything else, he shares much of the statist, nationalist, and populist ideology espoused by the others in the third left.

AMLO has been an exponent of this approach with his constant attacks on Mexico’s independent institutions, from the electoral authority and the National Institute for Transparency to various civil-society organizations and the media. Little has come from this offensive; but as his administration winds down, the risks of a more sweeping crackdown may be growing. With energy policies that are not only environmentally regressive but also highly statist and nationalist, AMLO has been harking back to the era of powerful, corrupt, and inefficient state oil and power monopolies. He is thus hard to differentiate from classically populist, anachronistic Latin American leaders of the past.

Beyond the obvious differences between these leftist leaders’ styles and platforms, the idea of a “new pink tide” goes only so far. While all Latin American economies have been battered by the 2020 recession, some countries are simply confronted with much tighter constraints than others are. Poverty and inequality have risen, tax revenues have declined, and the recovery is taking longer than expected.

In these circumstances, meeting voters’ demands will not be easy. Despite politicians’ best intentions and the enthusiasm of their supporters, electoral victories do not guarantee radical social change. Notwithstanding their fulminations against free trade, for example, Boric, Castillo, Petro, and AMLO have shown no willingness to withdraw from their countries’ free-trade agreements with the US.

There is no new pink tide in Latin America. Rather, there is a diversity of governments and movements that often rely on similar rhetoric, but whose substantive differences are more significant than their similarities. In this respect, the region should consider itself lucky.