Jewish and Muslim v AIPAC in DC

Muslim staffer tried to organize separate vigil, honoring both slain Israelis and innocent Palestinians who had been killed, although it would be too harmful to her career.

Richard Joseph ‘Dick’ Durbin (born November 21, 1944) to be 1st ever US Senator calls for CEASEFIRE. Wonder how Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Ann Warren feel [also President Biden feel] about Dick Durbin - the second-highest-ranking Democrat in the Senate - being willing to call for a ceasefire, when they haven't. Durbin, AIPAC’s First successful recruit, becomes first Senator to call for Gaza Ceasefire.

Wonder if Durbin will be called "repugnant" or if the White House only has that kind of smoke.

Earlier October, Adam Ramer started a new job. He was just four years out of college, and this would be one of his biggest jobs yet: political director for the reëlection campaign of Ro Khanna, a Democratic representative from Silicon Valley.

Khanna, a well-known and popular incumbent with plenty of money in the bank, is in no real danger of losing his election next year; many representatives in his position might not have been hiring campaign staff at all.

But Khanna is also ambitious—it’s frequently speculated that he may run for President one day, staking out a pragmatic-populist lane slightly to the right of Bernie Sanders and to the left of Gavin Newsom. Part of Ramer’s job would be to act as a liaison between Khanna and various activist groups, trying to keep the representative in the good graces of his progressive base and to burnish his future reputation.

On October 7th, Ramer’s sixth day on the job, he woke up to the news that Hamas militants had broken through the border fence in Gaza and started slaughtering and kidnapping Israeli civilians. “My first reaction was to be sickened by the bloodshed,” he said. “My second thought was, When Israel responds, it’s going to get so much worse.” Ramer, a redhead with a mustache, is descended from Mennonite pacifists on both sides of his family.

His grandfather, a conscientious objector during the Vietnam War, was later arrested while scattering blood on the walls of the Pentagon, as part of a civil-disobedience action against nuclear weapons. (Ramer’s mother, then twelve, watched her father get arrested. “I’m scared, but I understand why he did it,” she told the Washington Post at the time, her glasses dotted with blood.) In conversation, Ramer talks less about earmarks and executive orders than about vines and fig trees. “I hate politics,” he said. “But it’s the most direct way I have found to try to reduce people’s suffering.”

Ramer was working remotely from Madison, Wisconsin, dog-sitting for his parents while they were on vacation. (They were not on a cruise or at a Club Med; they were on a group tour of Northern Ireland, learning about the protracted peace process that ended the Troubles.) In the hours after Hamas’s attack, American and Israeli politicians started referring to it as “Israel’s 9/11” and invoking an unqualified right to self-defense, as if the magnitude of the atrocities could preëmptively justify whatever Israel did next. But Ramer reflected on what he took to be the abiding lessons of 9/11, and of its grinding, decades-long aftermath: “No matter how full of anger and legitimate grief you may be, how do you not turn that grief into endless war?”

Khanna was one of Bernie Sanders’s most outspoken supporters in the 2020 Presidential primary, but since then he has put distance between himself and other Sanders-aligned House members, including those in the so-called Squad. He refers to himself not as a democratic socialist but as a “progressive capitalist.” (He represents Silicon Valley, after all, and has received sizable donations from some of the rich men south of Richmond, California.) Ramer, who worked on Sanders’s campaign in 2020, went to work for Khanna knowing that he was not a doctrinaire leftist. “He’s strong on unions, on climate, on Medicare for All,” Ramer said. But it wasn’t clear that Israel-Palestine was at the forefront of Khanna’s mind—or any Democrat’s mind, really—until the events of October 7th.

Shortly after the Hamas attack, Khanna put out a statement condemning it—a statement that no one, or at least no one with any credibility in American politics, could have opposed. (A few leftists online, citing a superficial reading of anti-colonial theory, were memeing themselves into the position that wanton murder was actually praxis, but such views had no currency in D.C.) Ramer tried to urge his boss to move beyond denunciation and toward deëscalation: “We can condemn Hamas unequivocally while standing unequivocally with Palestinian lives and decry the drums of war that are being hit right now,” he texted Khanna, who responded, “Yes, that’s what I try to do.”

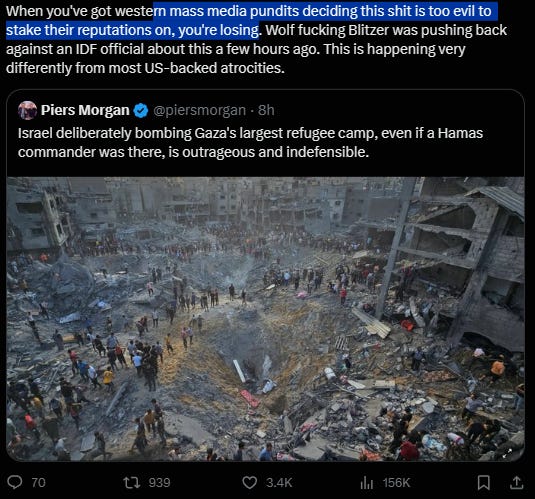

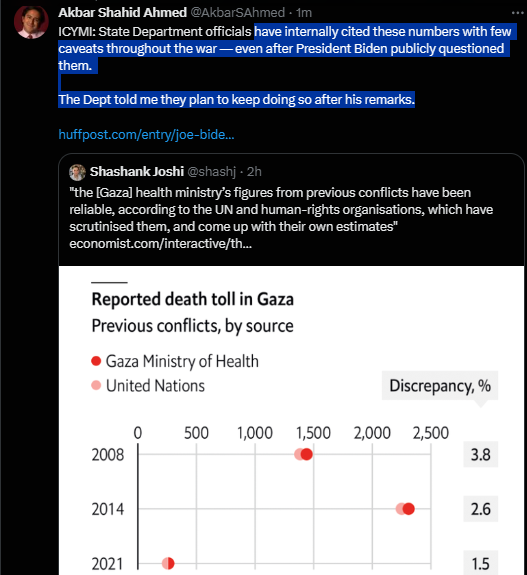

The Israeli Defense Minister, Yoav Gallant, ordered a “complete siege” of Gaza. “There will be no electricity, no food, no fuel,” he declared. “We are fighting human animals and are acting accordingly.” Nearly nine hundred scholars warned that such dehumanizing rhetoric (“human animals”) has, in the past, been a precursor to genocide. When the air strikes started, killing thousands of Palestinian men, women, and children—and then again, when Isaac Herzog, the President of Israel, reiterated, “It is an entire nation out there that is responsible”—many observers argued that Israel was carrying out a policy of collective punishment, making the civilian population of Gaza pay for Hamas’s crimes, which, international experts noted, is a war crime.

House members held a candlelight vigil for Israeli victims of Hamas, and Khanna attended. (A Muslim staffer who works in another progressive Democrat’s office told me that she and a few other Hill staffers, both Muslim and Jewish, tried to organize a separate vigil, honoring both the slain Israelis and the innocent Palestinians who had been killed, but that several colleagues advised her against it, saying that it would be too harmful to her career.)

More than four hundred representatives co-sponsored a bipartisan House resolution whose official title was “Standing with Israel as it defends itself against the barbaric war launched by Hamas and other terrorists.”

The resolution rightly mourned Israeli and American deaths, yet it referred to Palestinian civilian casualties only in passing, and with little sympathy; it pledged “support” for Israel with no stated preconditions, and made no mention of international humanitarian law. Still, J Street, a center-left lobbying group that describes itself as “pro-Israel, pro-peace,” was joining with groups to its right, like AIPAC, to push representatives to co-sponsor the resolution. Some pro-Israel lobbyists seemed to be implying that almost any attempt to constrain Israel’s military options would be understood as a betrayal.

This was another way in which the days after October 7th resembled the days after 9/11: a consensus was starting to take hold in Washington, one in which public calls for deëscalation were portrayed as soft-brained lunacy or traitorous extremism. “The pressure I was getting from activists was, ‘Are we just giving Israel a blank check?’ ” Ramer told me. “People noticed that there were thirteen members who had decided not to co-sponsor that resolution, and I heard from a bunch of people asking why Ro wasn’t one of them.”

The short answer, it seemed, was that the political lines were becoming clearer, and Khanna was trying to avoid finding himself on the wrong side of them—or, really, to avoid being too strongly associated with any side, if he could help it. “Most politicians see Israel-Palestine as a no-win issue,” a Democratic operative told. “The people who care most about the issue are hard-core Zionists and Arabs with relatives living under apartheid, and everyone else mostly doesn’t give a shit.”

Even Bernie Sanders, the most consistently pro-Palestinian senator (he also once lived in Israel), was not eager to take a vanguardist position on the issue. “He finds the Israel situation depressing, and he’s annoyed that people are talking about this instead of the labor strikes,” a progressive political staffer told me.

Pramila Jayapal, a representative from Seattle and the chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, co-sponsored the bipartisan resolution, although she privately expressed anguish about it. “She actually gives a shit about Palestinian lives, but she feels politically boxed in,” the staffer told me. Around this time, Jayapal told a colleague who ran into her at the airport that she felt compelled to support the bipartisan resolution, despite her misgivings—J Street and other pro-Israel groups had left her no choice.

In private, the Biden Administration was reportedly pressing the Netanyahu administration to delay a ground invasion of Gaza and allow in a trickle of humanitarian aid. Biden also think Netanyahu will be toppled by another politician. All the more reason, some members of Congress told their staff, to avoid taking a public position that could restrict Biden’s room to negotiate.

Some staffers considered this a principled stance; others thought that it was a convenient excuse. Ramer, alone with the dog in Madison, was up at all hours, doomscrolling. “You have one internal voice going, Adam, you just started this job, your role is to be respectful and not cause problems,” he told me. “And then there’s the other half of you that’s thinking, If there’s a chance of this spiralling into an ethnic-cleansing situation, or a world war, and there’s anything the American government could be doing now to prevent it, and here I am texting with a U.S. congressman, then I probably have a responsibility to keep pushing.”

American politics was bitterly partisan during the Presidencies of Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama, but one of the few areas of bipartisan consensus was staunch, often unquestioning support for Israel. The motif of an American left that was progressive “except for Palestine” became so familiar that Marc Lamont Hill, a CNN contributor who was fired after sharply criticizing Israel, used the phrase as a book title. But, beginning in Obama’s second term, two things started to happen simultaneously: the Democratic coalition shifted to the left, and Israeli politics shifted to the right. Democrats, both leftists and moderates, often spoke out against the authoritarian tendencies of Viktor Orbán, Jair Bolsonaro, and Donald Trump—the sort of tendencies that were also exhibited, with increasing zeal, by Benjamin Netanyahu.

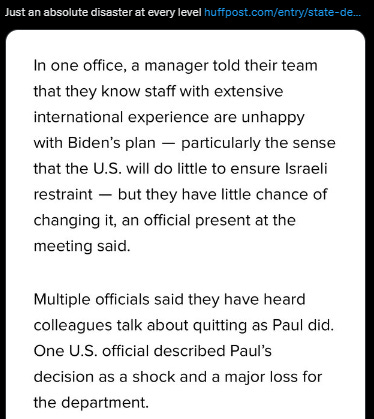

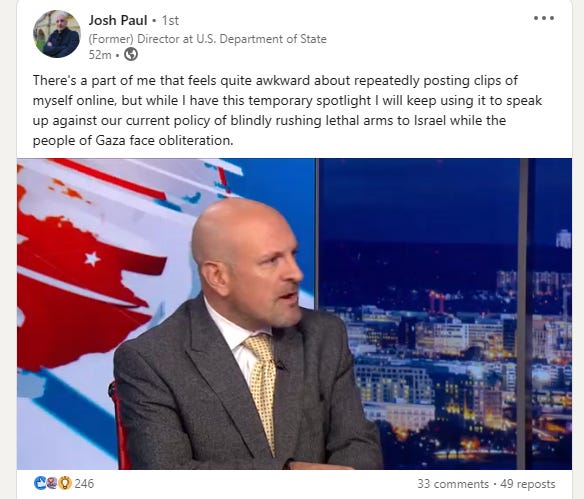

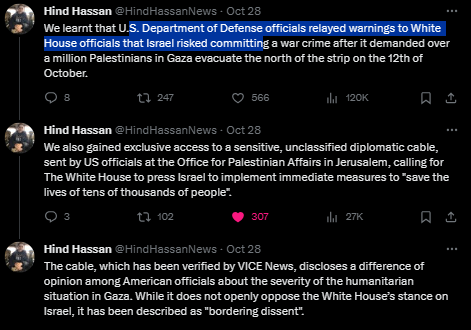

When the Israeli military started to react to Hamas’s attack, most Republicans, with the notable exception of Donald Trump, stuck to the old script, with comments ranging from darkly jingoist to candidly exterminationist. Within the Democratic coalition, though, surprising new fissures started to emerge. Ben Rhodes, Barack Obama’s former deputy national-security adviser, and Thomas Friedman, the stalwart moderate of the Times Opinion page, found themselves to the left of Senator John Fetterman, a salt-of-the-earth left-populist who also turned out to be an acerbic Zionist. Josh Paul, a high-ranking State Department official for more than a decade, resigned in protest of “our continued lethal assistance to Israel.” Nearly every institution—campuses, synagogues, families—seemed riven by internal conflict.

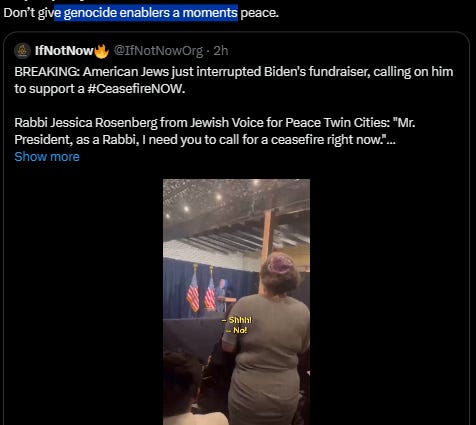

Beginning on Monday, October 16th, Ramer said, “movement folks started coalescing around a single demand”: a ceasefire in Gaza. In particular, he mentioned two left-wing Jewish groups: IfNotNow, founded in 2017, and Jewish Voice for Peace, founded in 1996. For its first two decades or so, J.V.P. was a source of tsuris within the Jewish-institutional world, but far from a political powerhouse. In recent years, though—and especially in recent weeks—both groups had seen a sharp increase in volunteers. “The old-line Zionist groups thought they had a monopoly on this issue,” a prominent Jewish critic of Israel told me. “Now they’re freaking out because the next generation is joining the opposition—their kids are joining.” Two members of the Squad—Cori Bush, a former Black Lives Matter organizer, and Rashida Tlaib, the only Palestinian American in Congress—introduced a House resolution calling for a ceasefire. At one point, the progressive political staffer told me, “we had the text of the resolution, but we were wondering whether to wait and get someone to introduce it who would be perceived as less polarizing, like maybe Pramila or Mark Pocan”—a white progressive from Wisconsin who is not seen as a firebrand. “But then the feeling was, This is too urgent. Let’s just put it out, and if it’s perceived as a Squad thing, and other members feel they can’t touch it, then so be it.”

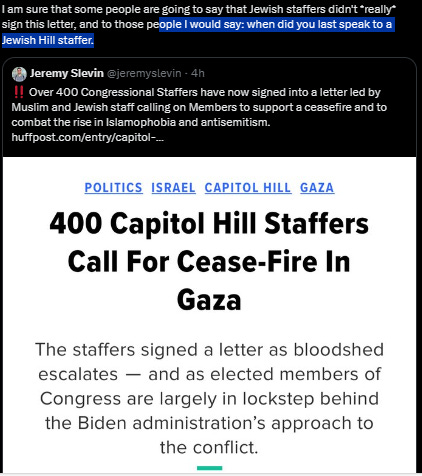

This was more or less what happened. The word “ceasefire” became a shibboleth splitting the left in two, with politicians like Khanna and Jayapal, and even Sanders, stuck in the middle. The ceasefire resolution was introduced with thirteen co-sponsors—members of the Squad and their allies, essentially—all of whom were people of color. Waleed Shahid, a former staffer for Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, tweeted, “I’ll buy gulab jamun for the first white member of Congress to endorse ceasefire in Gaza.” More than three hundred of Sanders’s former staffers signed an open letter, and more than two hundred and fifty of Senator Elizabeth Warren’s former staffers wrote another, urging the senators to join the call. Kunoor Ojha, who worked on Warren’s Presidential campaign, in 2020, told me, “I think she’s engaging in good faith, but I suspect the pressure she’s feeling from the other side is way more acute than what we’ve seen on other issues.” J.V.P. and IfNotNow started organizing demonstrations in support of the ceasefire resolution; aipac started whipping votes against it. (“A ceasefire would only serve to leave Hamas armed and in power,” David Gillette, an aipac lobbyist, wrote in an e-mail to congressional staffers.) Shortly after the air strikes on Gaza began, Antony Blinken, the U.S. Secretary of State, had tweeted in favor of “advocacy for a cease-fire”—on its face, not an outlandish position for a diplomat to take. But this was cast as a dangerous capitulation—“The Biden Administration is showing its true colors,” a Republican representative from Florida wrote—and Blinken deleted the tweet.

J.V.P. and IfNotNow led a rally on the National Mall, and five thousand people showed up. “We will not use the fact that many of our parents and grandparents and great-grandparents were refugees from genocide to justify making hundreds of thousands or even millions of new Palestinian refugees,” the author Naomi Klein said, addressing the crowd. After the rally, more than three hundred protesters, including two dozen rabbis, entered the Cannon House Office Building, where they occupied a rotunda for hours, chanting and davening and blowing shofars, until they were arrested by Capitol Police. Phillip Bennet, a staffer for Representative Summer Lee, could hear the commotion from his desk, and he visited during his lunch break. “I found it surprisingly beautiful,” he said. “I felt like I was in temple again.” He and another congressional staffer made the impromptu decision to join the group and get arrested. “Everyone was wearing these matching black T-shirts that said ‘not in our name,’ ” he continued. “I was the only guy in the jail cell with a suit on.”

At the same time, down the hall, Klein and Beth Miller, a J.V.P. staffer, were rushing among meetings with about a dozen members of Congress. “We talked to members who were still on the fence, and some of their staff was pissed at them for not taking a stand,” Klein told me. An “inside-outside strategy,” she continued, “only works if you can build enough outside pressure to make your demands heard, and if there are people on the inside who are willing to be pressured. This was the first time, after decades of agitating from the left on this issue, when I’ve seen both of those factors coincide.” Barbara Lee, the only member of Congress to vote against the authorization of the use of military force three days after 9/11, was wavering about the ceasefire resolution; by the end of the day, she had agreed to become a co-sponsor. The same afternoon, an organizer with IfNotNow told me, they called a staffer in Jayapal’s office and said, “Just so you know, about fifty young Jewish activists are on their way to Pramila’s office later today, and they’re either going to be delivering a letter thanking her for joining the ceasefire resolution or they’re going to be doing a sit-in to protest her for not joining.” The staffer responded, “Copy that,” and hung up the phone. (A spokesperson for Jayapal denied this version of events.) Shortly after, Bush’s office heard that Jayapal wanted to co-sponsor the resolution.

Khanna still had not endorsed a ceasefire. The day the resolution was introduced, Adam Ramer, in his texts with Khanna, ramped up his internal advocacy. “People are reaching out and calling on us to support this resolution,” he wrote.

“Who is?” the representative responded. Ramer listed various groups, including J.V.P. and IfNotNow. “Can offer JVP and ifnotnow a zoom,” Khanna responded. Ramer said that he would try to placate the activists with a Zoom, but reiterated, with mounting urgency, that the movement was focussed on the demand for a ceasefire. Khanna demurred, writing, “Even Bernie has not called for this.”

“Just because Bernie and Biden admin is taking this line does not mean it is aligned with the progressive foreign policy moment,” Ramer wrote. “We are burning goodwill and the support of the organizers that I am here to build with.”

“Won’t go further than Bernie/Warren on it as very complex,” Khanna texted. “So we need to highlight statements I have made—which is further than Buttigieg, Kamala, Newsom, Whitmer.” This was clearly his final answer. Ramer responded to the text with a thumbs-up emoji and put down his phone.

“I sat with that for a few hours,” Ramer told me. “I took a long walk in a park I really love. And I made up my mind: this is my red line.” That evening, he wrote Khanna a resignation letter. “I cannot in good conscience continue in this role,” he wrote. “Continued escalation will only kill more Israelis and Palestinians, and will impact American lives as well.” Khanna responded swiftly and tactfully: “You are a man of conviction. I respect that.”

The following day, Ramer took a pre-planned flight to New York; the day after that, he and a few friends drove to D.C., to join the rally on the National Mall. By the time he made it to Capitol Hill in person, he was no longer a political staffer, just another protester in the crowd.

Two Fridays ago, in the pouring rain, I joined Adam Ramer at another protest, on the steps of the New York Public Library. “Never Again Means Now,” the banners read, and “Free Palestine,” and “Colonized Since 1948,” and “Ceasefire Now.” Separately, across the street, a lone protester—or maybe a counter-protester, it was hard to tell—marched in tiny circles, holding a cardboard sign. “Jews Control US, UK & EU,” one side read. In case that was too subtle, on the other side were just two words: “rich jews.”

There were a few hundred people, a damp expanse of umbrellas and ponchos and keffiyehs and yarmulkes, filling the space between the steps and Fifth Avenue. They listened to a half-dozen speeches and then started walking east, toward Senator Kirsten Gillibrand’s office. At one street corner, the protesters walked past two Israeli women who sat in a stopped car, seething with rage. “You support the terrorists!” one of the women, Sigal Gordon, screamed, honking and giving the protesters the finger. “You want women to be raped and murdered?”

One of the protesters turned to face her. “Where does it say ‘Hamas’ on my sign?” she shouted. “Show me where!” Her sign read “Let Gaza Live.”

I identified myself as a journalist and asked Gordon what she thought of the protesters. “They’re all terrorists,” she said. “Me, personally, I would murder all of them.”

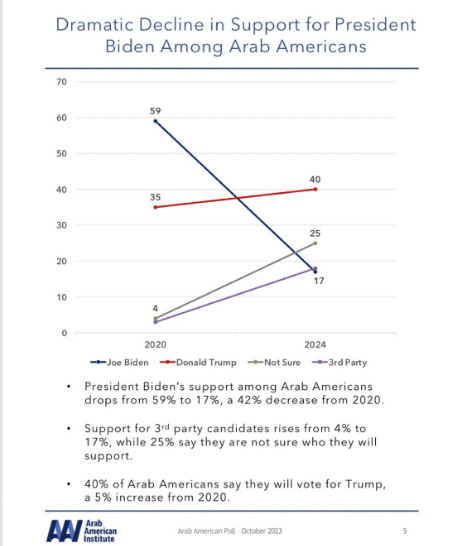

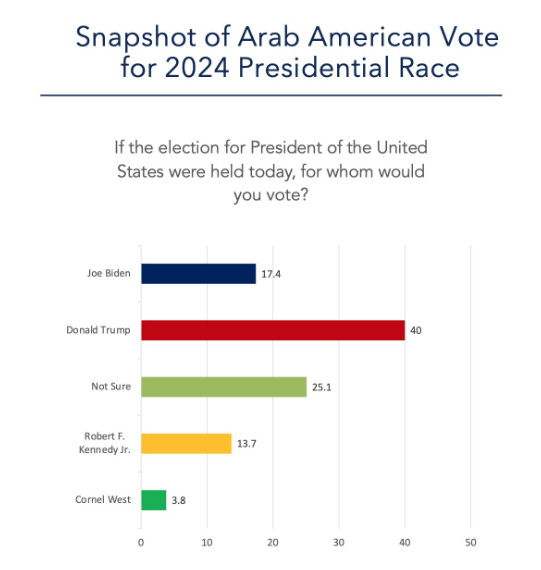

As of this writing, the ceasefire resolution has eighteen co-sponsors, out of four hundred and thirty-five House seats; it’s unlikely that it will ever come up for a vote. “Five years ago, that number absolutely would have been zero,” the progressive political staffer told me. “Now it’s eighteen. That’s kind of encouraging. It’s also crushing, because that’s how much power we have, and it’s nowhere near enough.” Still, previous Presidents, in similar binds, have faced significant pressure almost entirely from flag-waving nationalists on the right; Biden is now being cross-pressured from his left, and this seems to be having an effect. “My guess is the Dems will find a way to triangulate,” the Democratic operative told me, on October 23rd. “The Squad supports a ceasefire, so they can’t be for that, but, now that that’s the left flank of the debate, they can support something else—a cessation, maybe, or a truce.”

The following day, it became clear what that something else would be: a “humanitarian pause.” On October 24th, Antony Blinken told the U.N. that “humanitarian pauses must be considered”; the day after that, Bernie Sanders gave a speech on the Senate floor calling for a “humanitarian pause”; by the end of last week, Khanna had echoed the phrase, as had Jamie Raskin, Dan Goldman, and several other House Democrats, and NBC News reported that “the White House is now backing the idea of a ‘pause.’ ” In hindsight, it was reasonable to call for caution after 9/11, and I have joined in similar calls for caution now, signing an open letter in support of a ceasefire. “If there’s any lesson here, after we get past this war, it’s that the U.S.’s desire to pivot away from the Palestinian issue was a colossal blunder,” Khanna told me recently. “We can’t just wish away the desire for Palestinian justice.”

In New York City, the protesters stood outside of Gillibrand’s office and made a few more speeches, and then more than a hundred of them sat on the wet street, in orderly rows, waiting to be arrested. A socialist brass band called Brass and Roses played, keeping morale high, and someone with drumsticks played a bus-stop shelter like a snare. The arrests began around 8 p.m.; the protesters were flex-cuffed and loaded, with deliberate slowness, into double-length city buses. A young woman next to me held two burning candles in her hands. “I observe Shabbat, but I felt like I had to participate in this,” she told me. Ramer, who had volunteered to do jail support, collected people’s belongings before they were arrested, then took a subway to 1 Police Plaza and waited for them to get out. The last of them were released at one-thirty in the morning. When I talked to Ramer about Gaza, after we had gone over all the political and legal and geostrategic arguments, he made a theological argument, the same one that Abraham makes in Genesis 18: “If there be fifty righteous men within the city, wilt thou also destroy and not spare the place?”

![Heinous - Heartless Language by Biden and Blinken Haunted Not Only Arab - Muslim in US soil but Arab - Muslim [and Palestinian] Globally Forever](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1300,h_650,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8e3d8bfc-8a64-4bff-be01-3848e487cfc9_315x515.png)