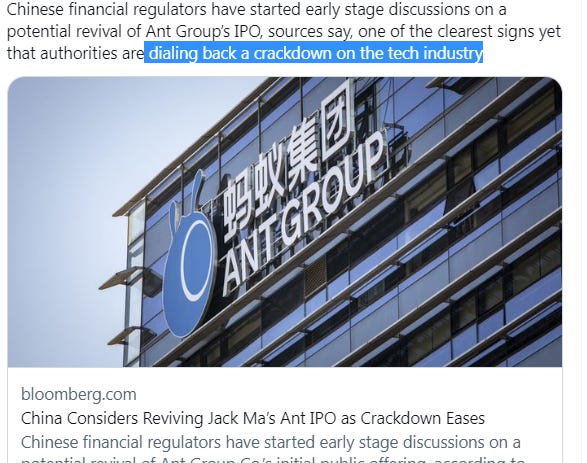

Competing with China will not be easy. But it starts with recognizing that right now the United States is losing. For comparable about building a powerhouse or something: China's Type 003 uses new electromagnetic catapult technology akin to what the U.S. and French carriers have to launch aircraft. All signs point to this progress continuing for its fourth, fifth and maybe even a sixth carrier only in 10 years from now (2022-2032). The U.S. has 11 carriers. Year late and neglected many major issues facing the two superpowers in the world.

The dilemma for the US at the moment amid in FP (Russia-Ukraine) & domestic (gun, milk formula, debt student): an outright commitment to 'boots on the ground' will end US-China relations, something the US is not willing and will not do in a long time. all sides will accelerate the preparation work, meaning all inch toward conflict when such gaffes happen. No easy way out. For example: No one wins a trade war because costs rise on all sides. If that’s the case, the U.S., which started the fight and eventually slapped steep tariffs on 3/4 of everything China sold to U.S. to force changes in Chinese economic policy, lost by not winning.

The fact: US still leader, promising even between China societies. The day the US truly declines is when visa lines in front of its consulates are no longer crowded ---- and currently still very long queue. Also, the power index is interesting, showing the US is still the leader in Asia. Not China.

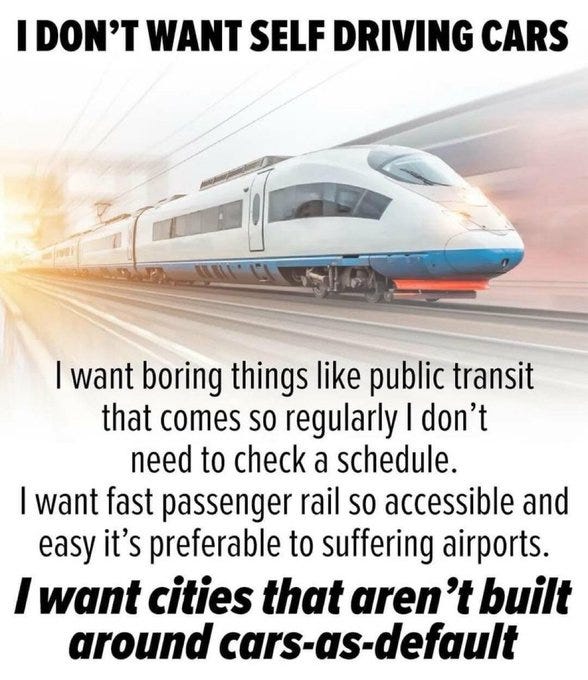

But everyone must admit U.S. never ever can built something very accelerate like China had. China set 60k km toll road and 10k km maglev-style of trains. Still impossible AmTrak will built gigantic level like this even amid Biden program "Build Back Together".

For another each impressive example of speedy construction from the early or mid-20th century, Patrick Collison (CEO of Stripe) includes a beleaguered project from today’s world for the sake of contrast: for example, the New York Subway system opened with 28 stations in 1904, just four and a half years after the first contract was awarded. By contrast, the 2017 Second Avenue subway opening, with just three stations, took seventeen years.

That might be a fine system if you’re already happy with the infrastructure you have, and living in a time of relative peace and stability. But we’re not, and we aren’t.

In recent years we have seen serious shocks to our economic order. Events like the Coronoavirus / COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine—or, on a longer time frame, climate change—have forced us to speedily reassess how we do business, in substantial and material ways. Importantly, these shocks don’t just call for a response in the financial world, like shuffling about some numbers on a computer. They call for real, physical responses—like redesigning city infrastructure or constructing new power plants.

Today’s high gas prices are the perfect example. Americans are universally unhappy about the high short-run costs of energy and transportation. And in the longer run, they aspire to make our economic life more independent of foreign dictators and their wars.

This isn’t a pie-in-the-sky aspiration. We could start doing this now, with the technology we already have. We could break ground on power plants to supply more energy. For a wealth purpose amid unpredictable crisis, we could reduce energy demand by building public transportation projects, or build homes more densely to shorten commutes and save on heating.

But these things are easier said than done. Not because we lack the construction workers or the engineering expertise, or even readily drawn-up plans, but because there are legal and political structures that stop each of those ideas from happening through procedural delays.

At best, this is an annoyance that wastes billions of dollars and years worth of time. At worst—at least, if you agree with climate change hawks—it’s the end of the world. AOC (Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez) believes in an urgent need for greener infrastructure, at any cost.

Forget how we pay for it, for a moment. The bigger problem is that urgency just isn’t there, money or no money. Ocasio-Cortez represents parts of Queens and the Bronx, where you might imagine public transit would be part of the green infrastructure mix. But new subway stops take decades, and are scarcely built anymore. Queens hasn’t gotten a new subway station since October 1989, the month she was born. The Bronx hasn’t gotten one since May 1941.

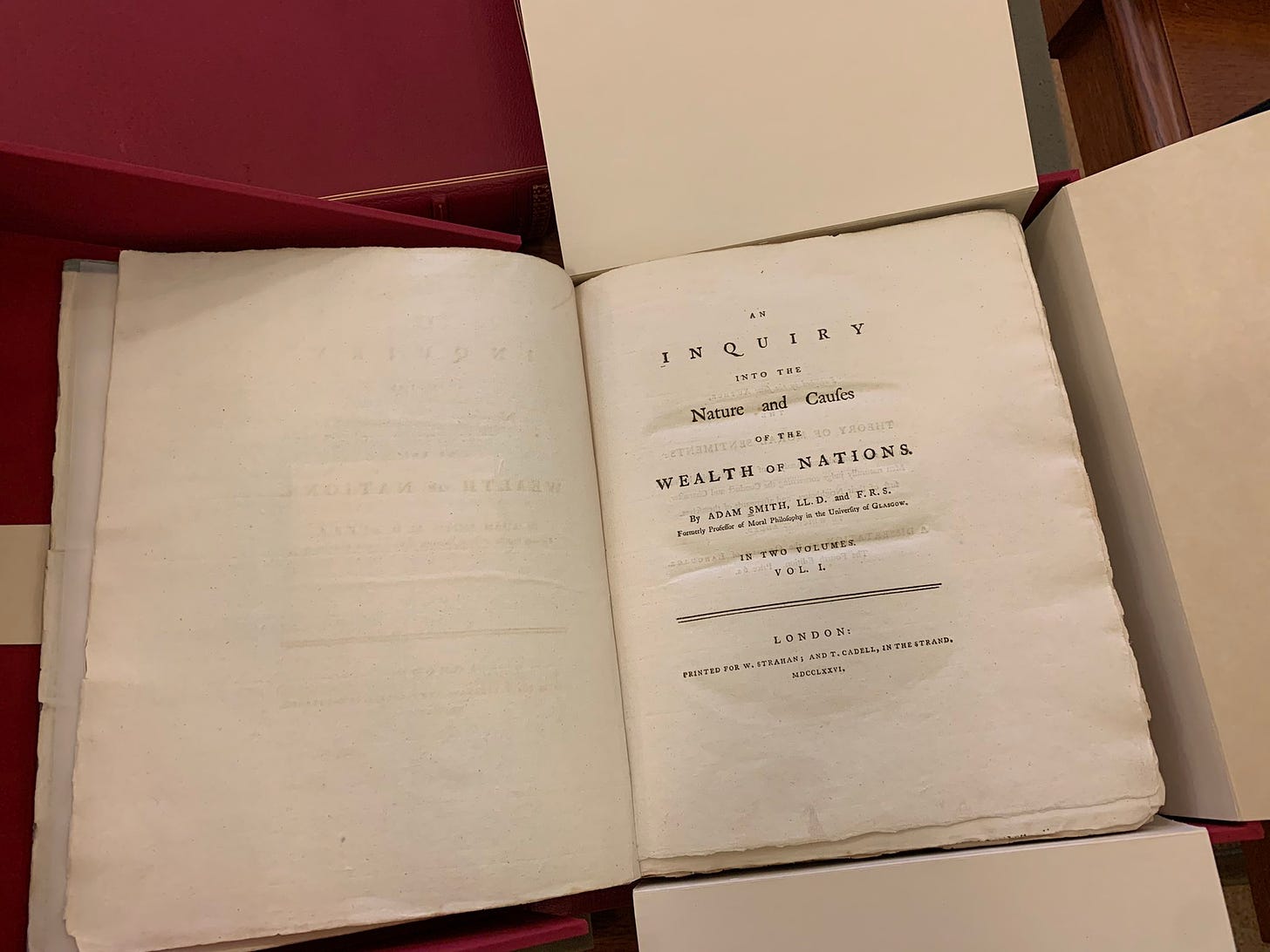

Economists call this a negative externality. There are a few ways to deal with negative externalities. Athur Pigou recommends a tax, ideally in the amount of the harm. Sometimes—as Ronald Coase showed—the parties can negotiate a side payment to efficiently handle the harm.

But they were aware of the limits of their solutions. Sometimes you don’t know how much the harm is, or the parties can’t negotiate efficiently among themselves. At this point, you need to make policy choices, one way or another.

And this is where I feel that lawmakers of the 1970s (Nixon saga on Viet Nam & Watergate; then Oil Embargo by Saudi, etc) made a huge mistake. Rather than accept the need for general rules, or choices by accountable elected officials, the lawmakers built a dispersed power structure filled with veto points that lends itself to analysis paralysis.

The problem with processes where you spend a long time gathering information and hearing arguments before you take action is that they are heavily biased towards maintaining the status quo.

Let’s say you think something should be done, and I don’t. While we work on our disagreement, nothing gets done. This isn’t a good structure for speedy resolution of disagreements, because I am incentivized to make the process longer.

The key tool that opponents of action have available is lawsuits. They can sue the state for permitting projects they don’t like—not because they can prove a decision was wrong on the merits, but simply because the environmental review didn’t sufficiently evaluate their concerns. This forces the government to go back and write an even longer environmental impact statement. Such a move might not change the ultimate decision, but it drags out the process for a few more months or years.

Activists argued that expanding enrollment at Berkeley was an action subject to environmental review, and that the state had not sufficiently studied the impact of Berkeley enrollment. Critically, they didn’t need to prove that raising Berkeley’s enrollment would actually harm the environment. They simply argued that Berkeley enrollment hadn’t been adequately studied, and that was enough—at least until the legislature overrode the court decision.

By expanding Biden government’s scope to handle small externalities, and unquantifiable ones, they’ve created a system where few things are doable as-of-right, everything is up for debate, and people are incentivized to exaggerate or even fake grievances.

Much of the change aversion built into our political systems reflects people’s sincere preferences, especially at the local levels. But I think reforms can be made at the macro level. I doubt people ever intended for our infrastructure-building process to become so frozen as it is, in aggregate. But we can fix it some, by reining in lawsuit-based case-by-case input processes and returning towards clearly-defined laws and executive decisions by elected officials. And for U.S. situation currently now: a damage 4 years by Trump absolutely can't solved in (in this time) 2 years of Biden, especially amid Coronavirus pandemic age.

Every country would like to build as quickly as China. All but the very few would hate to live in that communist style slave system. Big business/government would love it but they are the threat to humanity and the planet.