Fearful bureaucrats warn Anthony Norman Albanese Government not to anger the Americans. Attending a meeting “could carry risks for our strategic interests” — as we attended a mere meeting on the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, opposed by the U.S. Australian PM Penny Wong resisting advice not to "offend" the US. Time to Australia, “the staunchest allies of U.S.”, put big pants on and stop worrying about offending so-called 'allies' or trade partners. Diplomacy is also about retaining some resemblance of national sovereignty. The risk is not to “Australia interest" strategic interests but those of US ally. Australia fear "friend" (U.S.) more than Australia fear nuclear war in the future.

FOI documents reveal officials were nervous that going to Vienna gathering would be a sign of Australia wanted to join the treaty.

Penny Wong overruled her department and insisted on sending an observer to the first meeting of countries that support a landmark United Nations treaty banning nuclear weapons, new documents reveal. In Dec 7th, 2022, Wong issues emphatic plea to US and China to ‘prevent catastrophe’ of war.

A trove of documents obtained by Guardian Australia under freedom of information laws shows nervous officials warned the foreign minister of “significant” risks if Australia went to the gathering in Vienna shortly after last year’s election.

The irony of the U.S stating the TPNW "would not allow for US extended deterrence relationships..." when one of the biggest risks to Australia with regard to potential nuclear attack is, having a strategic U.S base in the middle of the country. DFAT must be seeded with US bureaucrats, wrote "TPNW wouldn't allow for US extended deterrence..." Sounds like they want Australia to provide the nuclear umbrella for US war with China ... You know, keeping nuclear war from continental US. Bureaucrats should be more 'nervous' about the US dragging us into another of its wars or the idea of any country seeing itself as our master. Spineless bureaucrats afraid of making America 'nervous' should learn from great Australian leaders and think bigger.

Those risks included that “Australia’s attendance could be misinterpreted as a first step” in actually joining the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), which is opposed by the United States and other nuclear weapons states.

Despite Anthony Norman Albanese championing the treaty prior to forming government, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade also issued a general warning that joining the agreement “could carry risks for our strategic interests”.

The relatively new treaty imposes a blanket ban on developing, testing, stockpiling, using or threatening to use nuclear weapons – or helping other countries to carry out such activities.

It now has 92 signatories, 68 of which have formally ratified it, and is strongly backed by neighbours such as Indonesia and New Zealand.

Australia has not yet taken steps to join the treaty, and continues to consider its position. The Labor party committed to sign and ratify the treaty after considering a range of factors that appear to be high hurdles to pass.

But anti-nuclear weapons campaigners were heartened by the decision to send government backbencher Susan Templeman to the Vienna meeting in June.

Australia followed that up by shifting its position at a UN committee in October to “abstain” after five years of actively opposing the treaty under the Coalition.

The newly released documents show Dfat formally recommended against sending an observer to the first meeting of TPNW members.

Officials conceded that attending would “attract praise from its proponents” and “may help to offset criticism … about Australia’s commitment to the international disarmament and non-proliferation regime”.

“However, in light of the ALP’s pre-election position on TPNW, Australia’s attendance as an observer could be misinterpreted as a first step in acceding to the treaty,” the submission to Wong in June said.

The department added that if the minister decided to send an observer anyway, “a concerted diplomatic effort will be required to mitigate the risks” and to “minimise the significance of the decision” to attend.

Wong circled “not agreed” to the main recommendation and asked for further advice about the impact of sending a backbench MP.

Dfat then provided a new submission saying that if Australia was the only country to send a parliamentarian as an observer “we will need to manage potential perceptions” and “shape the narrative”.

“Public messaging will be necessary in light of strong domestic and international interest,” it said in an attached strategy document.

“Key to any messaging … will be to highlight that no decision has been made on our broader approach to the Treaty.”

Gem Romuld, the Australian director of the Nobel prize-winning International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, said it was “time for Australia to dispense with the dangerous, outdated notion that nuclear weapons bring security”.

“It’s clear that certain officials at the foreign ministry are intent on maintaining the previous government’s unprincipled position on this treaty,” Romuld said.

“We’re pleased that minister Wong has insisted on taking a new direction.”

Labor’s national platform in 2021 included conditions for supporting the treaty, including working for universal support and effective verification and enforcement.

Wong’s spokesperson said the government was “engaging constructively to identify realistic pathways for nuclear disarmament” and that was why the minister had signed off on Templeman’s attendance as an observer.

“The government will consider the TPNW systematically and methodically as a part of our ambitious agenda to advance nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament,” the spokesperson said.

In November, the US embassy in Canberra warned that the TPNW “would not allow for US extended deterrence relationships, which are still necessary for international peace and security”.

That was a reference to Australia relying on American nuclear forces to deter any nuclear attack on Australia – the so-called “nuclear umbrella” – even though Australia does not have any of its own atomic weapons.

Wong’s spokesperson said there were “a number of complex issues to be considered” and Australia would “engage closely with our international partners – including the United States – as part of this process”.

“The government has reaffirmed that the US alliance remains central to Australia’s national security and strategic policy,” the spokesperson said.

The documents also reveal Dfat officials warned in August against uniting with other countries to sign a statement of concern about the humanitarian impacts of nuclear weapons.

The submission to Wong said: “While this might provide an opportunity to counter the narrative that concern for humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons must equate to support for the TPNW, the statement includes wording that nuclear weapons are never to be used again, ‘under any circumstances’. It is unbalanced.”

Dfat argued Australia had “already affirmed our deep concern at the humanitarian impact of weapons use”. In that case, Wong approved the official recommendation.

But Romuld said the statement was “a factual acknowledgement of the undeniably devastating humanitarian consequences of any nuclear weapons use, backed by over 140 governments and the International Committee of the Red Cross”.

Australian officials continue to emphasise the importance of the longstanding Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

Another document shows Australia’s goals for the NPT review conference in New York in August included “to provide reassurances that Aukus partners are steadfast in their commitment to the global non-proliferation regime and will set the highest possible standards in our acquisition of conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarines”.

In Sept 22 2022, Wong says 'these threats are unthinkable and they are irresponsible', after Putin references further heightening of Russia’s military response. 'His claims of defending Russia’s territorial integrity are untrue,' Wong says. 'No sham referendum will make them true. Russia alone is responsible for this illegal and immoral war.'

Australian MPs from across the political spectrum have called on the Albanese government to join a landmark treaty banning nuclear weapons, declaring that the weapons “fundamentally undermine our peace and humanity”.

In a statement provided to Guardian Australia, a cross-party group of MPs warned of “escalating nuclear threats and provocations from nuclear-armed states” and said Australia must play an active role to end the nuclear arms race.

The new treaty is a chance for Australia to stand with its neighbours in south-east Asia and the Pacific, according to the Labor MP Josh Wilson, the Liberal MP Russell Broadbent and the Greens senator Jordon Steele-John.

Speaking out on the second anniversary of the UN treaty coming into force, the MPs said the agreement was supported by “the clear majority of our regional neighbours with whom we share a common goal of peace, cooperation, and security”.

They called for Australia’s “timely signature and ratification”.

“The members of this cross-party group are ready to work constructively with the Albanese government to ensure Australia becomes a state party to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” the MPs wrote.

The US and other nuclear-armed countries are firmly against the treaty, which imposes a blanket ban on developing, testing, stockpiling, using or threatening to use nuclear weapons – or helping other countries to carry out such activities.

But the treaty now has 92 signatories, 68 of which have formally ratified it, and it is strongly backed by neighbours like Indonesia and New Zealand.

In opposition, Labor committed to sign and ratify the treaty, but only “after taking account” of several significant factors, including the need for an effective verification and enforcement architecture and work to achieve universal support.

Gem Romuld, the Australian director of the Nobel prize-winning International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, said the organisation hoped the cross-party statement would “spur the Albanese government on to fulfil its pre-election commitment”.

“Nuclear disarmament is an urgent humanitarian issue above party politics,” Romuld said.

“We can’t trust any of the nuclear-armed leaders to do the responsible thing and disarm; pressure from the global majority of nations, using the nuclear weapon ban treaty, is essential to move forward.”

The MPs said the treaty was intended to create a new international norm on the illegitimacy of nuclear weapons. They said history showed “prohibition treaties on weapons of mass destruction are essential to facilitate progress towards their elimination”.

Wilson, who is chair of the joint standing committee on treaties, said Australia’s peace and security was “massively improved when we help build and enhance the framework of nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament”.

He said the Albanese government had “wasted no time embarking on a serious and steady re-engagement” with both the longstanding nuclear non-proliferation treaty and also the newer ban treaty.

Australia attended a key meeting in Vienna in June as an observer. In a symbolic step in October, Australia changed its voting position on an annual UN resolution regarding the treaty, shifting to “abstain” after five years of “no”.

In November, the US embassy in Canberra warned that the ban treaty “would not allow for US extended deterrence relationships, which are still necessary for international peace and security.”

That was a reference to Australia relying on American nuclear forces to deter any nuclear attack on Australia – the so-called “nuclear umbrella” – even though Australia does not have any of its own atomic weapons.

But Indonesia’s ambassador, Siswo Pramono, said Australia’s positive shift on the treaty would “give encouragement to others to believe that we are on the right path” in seeking a world free of nuclear weapons.

In the mid-1950s, seven bombs were tested at Maralinga in the south-west Australian outback.

The combined force of the weapons doubled that of the bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima in World War Two.

In archive video footage, British and Australian soldiers can be seen looking on, wearing short sleeves and shorts and doing little to protect themselves other than turning their backs and covering their eyes with their hands.

Some reported the flashes of the blasts being so bright that they could see the bones of their fingers, like x-rays as they pressed against their faces.

Image caption,A cloud hangs over Australia's Monte Bello Islands after Britain tested its first atomic bomb

Much has been written about the health problems suffered by the servicemen as a result of radiation poisoning.

Far less well-documented is the plight of the Aboriginal people who were living close to Maralinga at the time.

'It was like a cancer'

"Every night I cry for them," Hilary Williams tells me as she sits around a campfire for an impromptu picnic of kangaroo tails laid on for our visit.

Her mother and grandparents all witnessed at least one of the explosions from just a few kilometres away.

Ms Williams said all three of them died young after suffering lung problems.

"It's so sad. They're not here anymore," she said, adding that she had heart problems she believes were also linked to the bombs.

Image caption,In June, Australia dropped plans for its first nuclear waste dump on Aborigine land

Locals around Maralinga spoke about a black mist of radioactive dust over their communities following the explosions.

"A lot of people got sick and died," said Mima Smart, an aboriginal community leader.

"It was like a cancer on them. People were having lung disease, liver problems, and kidney problems. A lot of them died," she said, adding that communities around Maralinga have been paid little by way of compensation.

'Not in our backyard'

Maralinga was chosen for its remoteness.

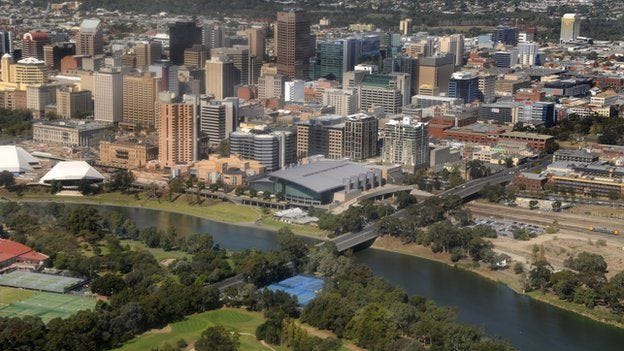

It's a ten hour drive to the nearest big city, Adelaide. But people here say that the Australian government was wrong to let the tests go ahead and that Britain acted irresponsibly.

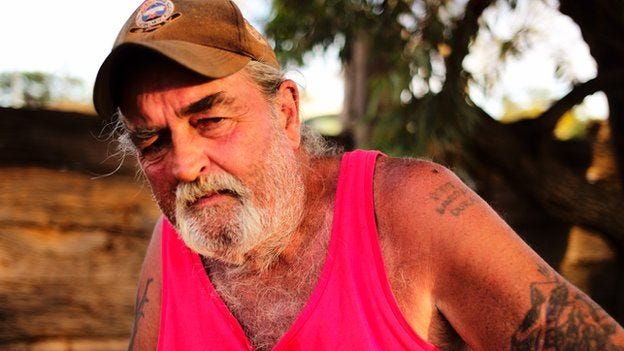

"They didn't want to do it in their own back yard because their back yard wasn't big enough," said Robin Matthews, caretaker of the Maralinga Nuclear Test Site.

"They thought they'd pick a supposedly uninhabited spot out in the Australian desert. Only they got it wrong. There were people here."

During the 1960s and 70s, there were several large clean-up operations to try and decontaminate the site.

All the test buildings and equipment were destroyed and buried. Large areas of the surface around the blast sites was also scraped up and buried.

But Mr Matthews said the clean-up, as well as the tests themselves, were done very much behind closed doors with a high level of secrecy.

"You've got to remember that this was during the height of the Cold War. The British were terrified that Russian spies might try and access the site," he said.

The indigenous communities say many locals involved in the clean-up operation also got sick.

'Sick land'

Maralinga has long been declared safe. There are even plans to open up the site to tourism.

But it was only a few months ago that the last of the land was finally handed back to the Aboriginal people. Most, though, say they have no desire to return there.

Mima Smart told me she regards Maralinga as sick land.

"I don't want to go back. Too many bad memories."

And even almost 60 years on, the land still hasn't recovered. Huge concrete plinths mark the spots where each of the bombs was detonated.

Around each, the blast area would have stretched for several kilometres.

The orangey red soil of the outback sparkles strangely green.

If you look closely, you can see the ground is covered with what looks like broken glass, where the soil got so hot it literally melted and turned to silicon.

And even after all this time, the natural vegetation still won't grow back.

"The grass here only ever grows a few inches," said Mr Matthews. "Even the birds and the kangaroos still stay clear of this area."

More than half a century on, most people here still regard Maralinga as a dark chapter in British Australian history.