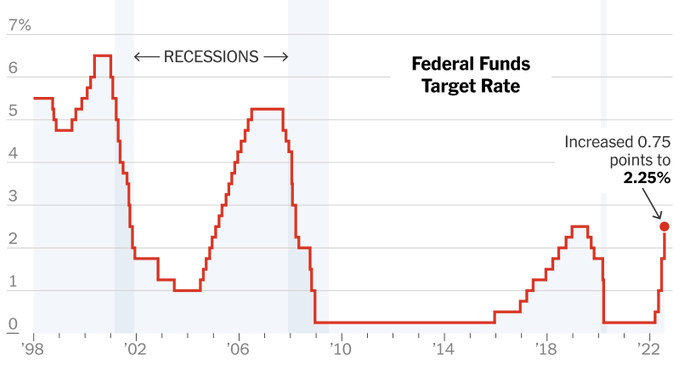

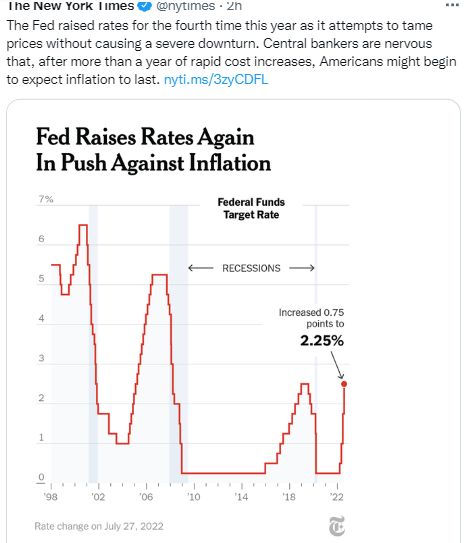

With raised .75 BPS by The Fed last month, and (tonight) raised again .75 BPS, and Powell (Chairman The Fed) with honest opinion said “too little knowledge about inflation”, contrary, the U.S. defense budget likely increasing will be the least surprising thing imaginable. If we focus merely on the capability of adversaries, we aren’t getting the full picture of things. Good policy requires good information.

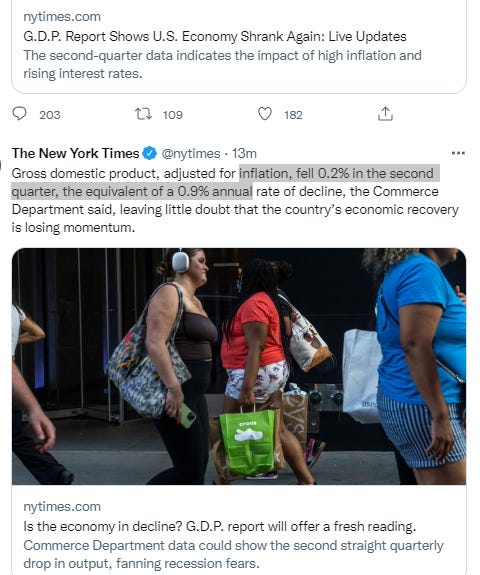

Conversely, bad information and threat-inflation produces bad, ineffective, and even dangerous policy. (and) If it’s not about keeping up with inflation, it’s about winning a hypothetical war against China. 52% of U.S. adults say they are worse off financially than they were a year ago, according to a survey conducted for The New York Times. Only 31% said they approved of President Biden’s approach to inflation.

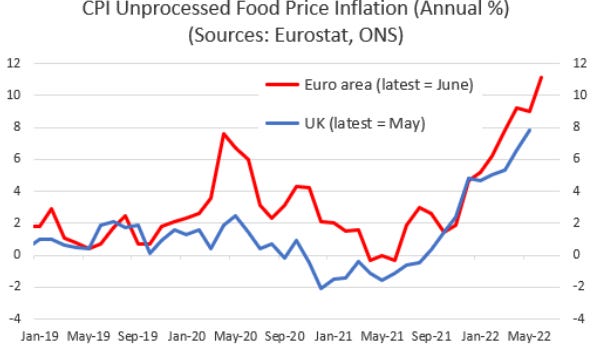

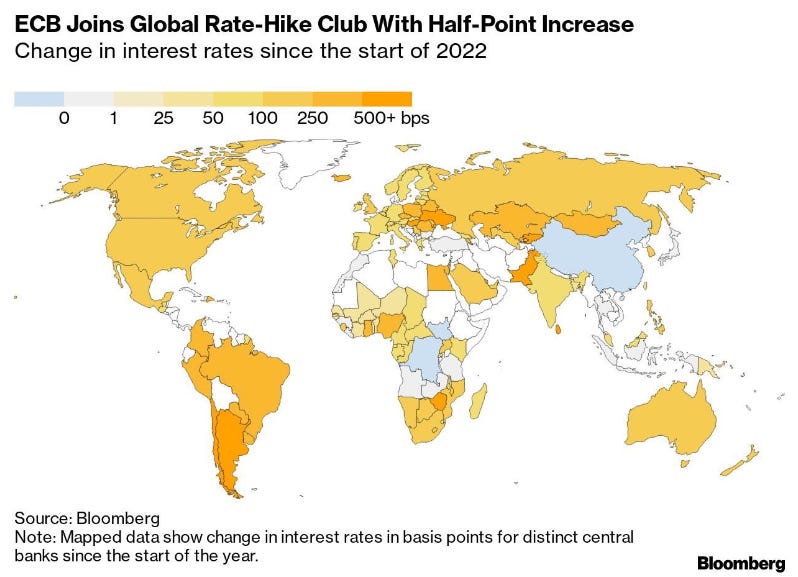

Inflation and supply chain issues were inevitable and not unique to the US. Inflation is at a 50 year high in Europe at 8.6%, the highest since the euro was created, driven by high energy prices. Nearly half of the 19 eurozone countries have reached double-digit inflation, according to the EU’s statistics agency. E

CB prepares for its first rate hike in 11 years. Europe is bracing for a summer of labor unrest as high inflation and labor shortages incite protests across the economy. The strife is most visible in transport, where workers at airlines, airports and railways are striking for better staffing and pay. Since inflation has worsened we are having a very difficult time making ends meet. Several people are too old to work.

Stable prices were a fact of life. A chain of supply bottlenecks has driven prices higher as companies fight to guard their profits and consumer demand remains high. Is it a post-pandemic blip that will resolve itself? Or a sign of more turbulence to come?

For people in finance, it’s a moment of extreme career risk—or a chance to be a hero to their bosses and their clients if they get it right. Many have never been here before. There’s people that are halfway, a third of the way through a career and they haven’t seen inflation.

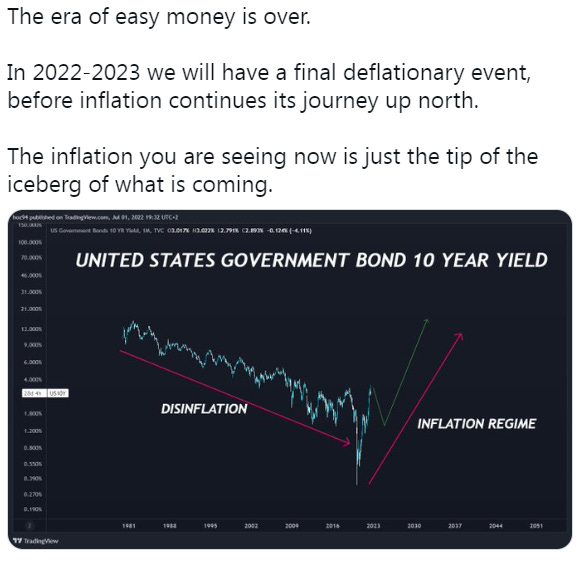

Inflation is the first hurdle every investor has to clear, and it’s baked into every pro’s model of the fair price to pay for a bond or a stock. But it’s not easy to get a read on how investors are processing the latest spike. Wall Street strategists are flummoxed. Of the 21 forecasters tracked by Bloomberg, the lowest year end target for the S&P 500 index is 3800 and the highest is 4800—that 26% spread is among the widest in a 2000 or 2010s decade. With inflation persisting, short term rates will need to rise as well further flattening the yield curve.

Central banks’ efforts to contain high and rising inflation are fueling growth headwinds and threatening to tip the global economy into recession. But the proximate cause of today’s inflationary pressures is a large, broad-based, and persistent imbalance between supply and demand. Higher interest rates will dampen demand, but supply-side measures must also play a large role in inflation-taming strategies.

Over the past year or so, the rollback of pandemic-containment policies has spurred a simultaneous surge in demand and contraction in supply. While this was to be expected, supply has proved surprisingly inelastic. In labor markets, for example, shortages have become the norm, leading to canceled flights, disrupted supply chains, restaurant closures, and challenges to health-care delivery.

In the Treasury market, volatility is surging. And a recent note from Goldman Sachs observed that the companies most beloved by hedge fund long traders are also the stocks most beloved by hedge fund short sellers—the ones who bet on stocks falling. In other words, professional speculators evidently expect the same stocks to rally and to plunge.

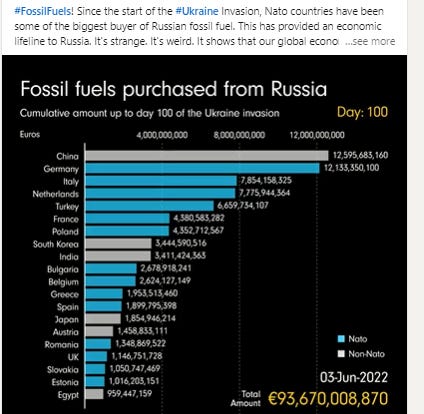

Inflation in countries using the euro set another eye-watering record, pushed higher by a huge increase in energy costs fueled partly by Russia’s war in Ukraine.

These shortages appear to be at least partly the result of a pandemic-driven shift in preferences. Many types of workers are seeking greater flexibility – including hybrid or work-from-home options – or otherwise improved working conditions. Health-care workers, in particular, report feeling burned out by their jobs.

If this is true, the inflation picture must include an adjustment in relative labor costs. To bring markets back into balance, wage and income increases will be needed, even for jobs for which there was previously an ample supply of workers.

In the long run, stocks are almost always a buffer against inflation: Good companies get to raise their prices—and profits—even as their costs go up. A year ago, some bulls liked to talk about the “reflation” trade, or a happy combination of booming growth and increased pricing power for companies.

For long-term buy-and-hold investors—including individuals investing their own money—this may make getting inflation “right” a less fraught problem. Thinking ahead for the next four or five years — because of too long coronavirus combat and also Russia-Ukraine saga. Inflation or not, that equation hasn’t changed. Inflation is more of a threat for investors facing shorter time horizons.

One risk for stocks is if inflation is so surprising and disruptive that it forces a sudden change in interest rates and market psychology—and causes investors to reassess their portfolios.

Recession nowadays will generate some inflationary pressure. Yes, nominal prices and wages have limited downward flexibility. But at a time of excess demand, firms generally try to pass on higher costs via price increases – and they often get away with it, at least for a while.

Lingering blockages associated with the pandemic, especially in China, which remains committed to its zero-COVID policy, are also fueling inflation. But these blockages will eventually subside, as will short- to medium-term capacity constraints caused by shifts in the composition of demand (in terms of both products and geography), though some will persist for a while. Capacity – whether in ports or semiconductors – takes time to build.

But today’s inflation has deeper roots. Over the past several decades, the activation of massive amounts of underutilized labor and productive capacity in emerging economies has generated deflationary pressures. With those resources having now been significantly depleted, the relative prices of many goods are set to rise.

Moreover, there is a global push to diversify and, in some cases, localize demand and supply chains – a response to the increasing frequency of severe shocks and rising geopolitical tensions. A more resilient global economy is a more expensive one, and prices will reflect that.

The war in Ukraine has not only accelerated this supply-chain transformation, but also has caused energy and food prices to skyrocket, further exacerbating inflation, especially in lower-income countries. In the case of fossil fuels, a prior pattern of underinvestment in capacity at multiple points along the supply chain has compounded the problem. For the moment, investors seem to care as much about having a haven as they do about staying ahead of inflation.

But what if that changed? To avoid losing even more money to inflation, fixed-income money managers might start demanding higher yields, which would mean forcing down bond prices. Pain in the bond markets could roil equities in a fashion similar to the late 1960s (Oil Embargo; Vietnam) to early 1980s (Iraq-Iran war; Lebanon-Israel). In a high-interest-rate environment, investors could reevaluate the prices they’ve been willing to pay for equities, bringing down price-earnings ratios even if profits remain solid.

What happens next may hinge on the Federal Reserve. The central bank after a .75 BPS hike rate, also begins reducing its bond-buying program this month and may end it by End-2022, and markets expect that a handful of interest rate increases will follow. It’s too soon to tell if inflation will speed up that timeline.

But there is even more to the story. More than 75% of the world’s GDP is produced in countries with aging populations. Old-age dependency ratios are rising, and in some countries, the workforce is shrinking. Productivity gains could counter the contraction of labor supply relative to demand, but after nearly two decades of falling productivity growth, such gains are not forthcoming.

So, inflation is rising fast, and central banks are under pressure to take drastic action. But their only real option is to reduce demand, by raising interest rates and withdrawing liquidity. These measures have already spurred a massive repricing of assets, including currencies, and they threaten to push global growth below potential, with lower-income economies suffering disproportionately, and to reduce investment in the energy transition.

There is another way: supply-side measures. Trade and investment have long enabled supply to expand rapidly in response to growing global demand. But, for nearly two decades – and especially in the last few years – proliferating trade barriers have been adding friction to this process. Creeping protectionism must be reversed, with US President Joe Biden removing the tariffs imposed by his predecessor, Donald Trump, and Europe accelerating the integration of its services markets.

At the same time, efforts must be made to improve productivity. Digital technologies will be crucial here. While the pandemic helped to accelerate the digital transformation, many sectors – including the public sector – are lagging, and concerns about the effects of automation on employment persist.

But in a supply-constrained world characterized by persistent labor shortages, productivity-boosting digital technologies, together with higher wages for workers, would go a long way toward improving the balance between supply and demand. For example, artificial-intelligence-based tools can perform a wide range of functions, from screening luggage more efficiently at airports to analyzing medical imaging to detect cancers. Beyond digital technologies, regulatory regimes can be streamlined and improved, in order to reduce supply-side bottlenecks.

Such an agenda must be applied to both the public and private sectors. At the international level, efforts to facilitate trade, address supply-chain rigid, and close data gaps will be essential. Otherwise, central banks will be left to deal with inflation alone – with dire consequences for the entire global economy.