Reiterate the World Order amid Unmitigated War, Unmitigated Stock Exchange, and Diseases

What the most upset globalization currently? When The West "with massive campaign" tightens sanctions to Russia, Russia (in statistic) earning more money from oil exports today than it was before the war in Ukraine began (February 24th, 2022). American and European policymakers evidently fooled themselves into believing that cutting off Russian oil would be the beginning of the end for Putin’s war machine. Not quite the result intended.

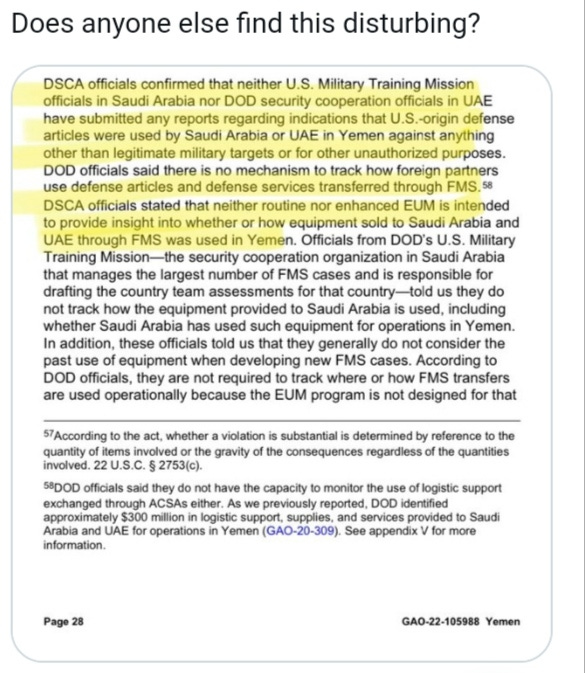

One of the face (of)globalization: delivery speed all The West to Ukraine is far more a priority than worrying whether aid will end up in the wrong hands. Furthermore, we do not know if weapons will be used in the “defensive” manner that Biden assures entirely the West they will. Until the fact that entirely also consume more energy from Russia even since war started (February 24th), contrary commitment (narrative) sanctions, using (old) style energy (coal from Asia) to life cycle “The West” Industries.

If governments get it right, a more subdued, but also more sustainable and longer-lasting kind of globalization will emerge. And in an open and growing world economy, peddlers of deglobalization theories will find it easier to change jobs and re-skill.

The left and the right united shall never be defeated,” claimed the Chilean poet Nicanor Parra, and the current debate over deglobalization illustrates the point. So-called progressives never liked fast growth in world trade and now greet any reversal with cries of “I told you so; I was told” Globalization-supporting conservatives, on the other hand, react to the smallest setback with Chicken Little-like cries that “the sky is falling.”

Both camps have an interest in exaggerating the extent of deglobalization. The result is a widely accepted narrative of decline: After repeated financial crises, a nativist reaction, the COVID-19 pandemic, and now Russia’s war on Ukraine, globalization’s days are numbered.

It’s an eye-catching claim. But is it true? Russia becoming a Chinese client state is concerning, as is Ukraine falling under Russia's influence. For the sake of American victory over a Chinese-led order, we cannot let Russia re-write our globalization, our World Order nowadays.

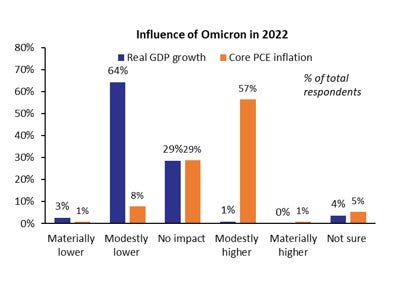

According to the World Bank, trade in goods and services as a share of global GDP fell from a peak of 61% in 2008, just before the global financial crisis, to 52% in 2020. But this figure is still very high by historical standards – the trade-to-GDP ratio averaged just 42% in the 1990s, when critics were already complaining about hyper-globalization. Once final data are available, they will show that trade recovered in 2021 and 2022 as the pandemic receded. There might be shortages of essential products, but there's no shortage of reasons to feel gloomy about the globalization economy today, whatever so painful - suffering recession. The dispersion of views about inflation and how that signals a shift in expectations and adds to inflationary spirals. Inflation becomes more of a vicious cycle when dispersion gets more broad.

More interestingly, the all-out tariff war predicted by trade skeptics never erupted. Starting in 2018, then-US President Donald Trump increased tariffs on some Chinese goods, China retaliated, and the dispute spilled over into a handful of other markets.

Biden initially found it expedient to keep some of Trump’s tariffs, but now plans to roll them back in an attempt to reduce US inflation, and actually try to ease global inflation when The Fed set 75bps rate. Once inflationary expectations get built into people’s financial planning, they become a self-fulfilling prophecy, and it is very hard to get them out.

The majority of the recent elevated core inflation (which itself is very high) is due to demand factors. And the demand component of core inflation is growing. Supply shock in one good led to reduced consumption in others. That would look like a negative demand shock but really was just supply. For example: inflation due to energy and food really do look like a supply shock--and one can infer/expect that this supply shock that will go away.

A worldwide escalation in tariffs and quotas will not happen, for the simple reason that voters do not want it to happen. In rich and poor countries alike, a parent can buy a pair of Chinese-made children’s sneakers for $10 or less. A generation ago, the only option in most places was a locally-made pair costing several times that.

Protectionism is supposed to be popular with voters, but the reality is subtler. As any pollster will tell you, the statement “government should do what it can to protect local businesses and local jobs” typically elicits overwhelming support. The statement “government should protect local industry even if that means much higher prices for consumers” meets with widespread derision. In reality, not like this. Biden administration has decided it can still convince oil companies to ramp up domestic production in the short term while simultaneously promising to adhere to the president’s ambitious climate change goals in the long term. And, the fact Macron lose Parliamentary majority (last week, Legislative Election) will haunted Biden towards midterms election next November.

Three big changes are afoot in world trade, but none of them need imply widespread deglobalization.

The first change is the reconfiguring of global supply chains. As the media have reported in gory detail, first the US-China tensions, then the pandemic, and now the Russia-Ukraine conflict caught many global firms – in sectors ranging from cars to baby formula – without a Plan B to source the inputs they need.

If Biden were a serious president, he would stop his war with American oil companies and encourage long-term investment in domestic production rather than trying to longer war. They are now switching from “just-in-time” to “just-in-case” supplies. “Resilience,” “near-shoring,” and “friend-shoring” are the buzzwords du jour.

The expansion of world trade over the past two decades resembled the Gold Rush or the dot-com bubble of the early 2000s. Firms that found the lowest-cost supplier internationally, with little regard for the risks involved, could make big money. Other companies followed suit because their competitors were doing it. Eventually, something had to give.

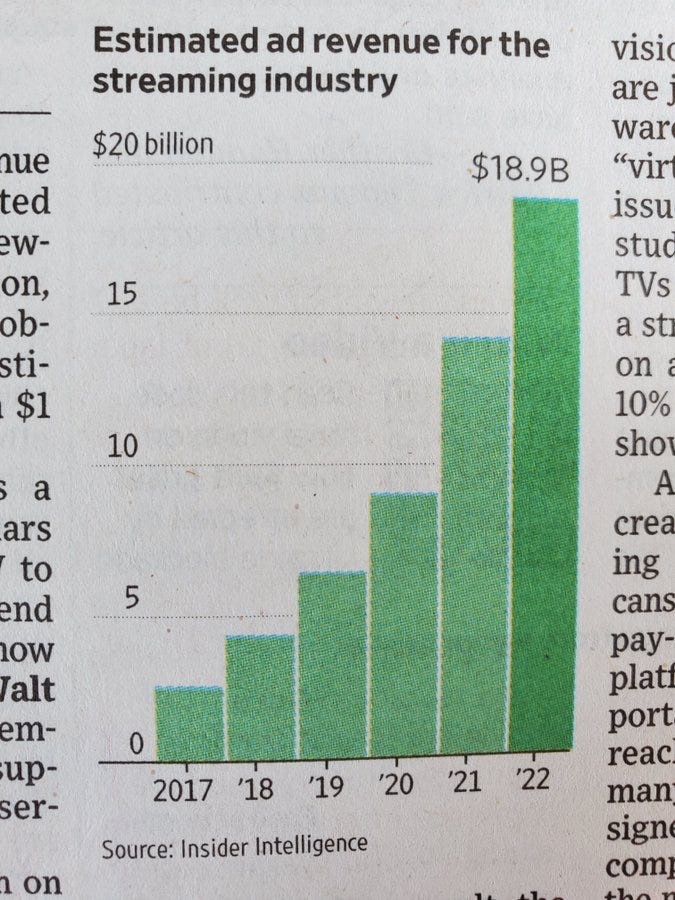

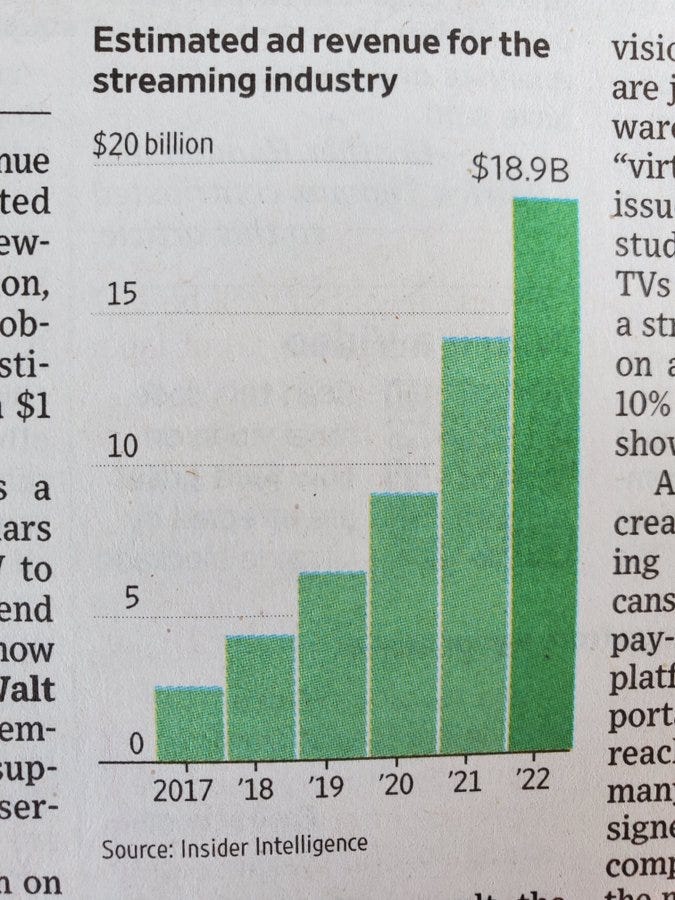

While the dot-com crash took away Pets.com, it gave us Facebook, Amazon, Spotify, Netflix, ZOOM, and TikTok. This time around, crises are causing firms to diversify suppliers and draw up plans B, C, and D. Costs will increase, but so will safety and reliability. Crucially, most supplies will still come from abroad. Apple recently decided to move some of its assembly operations from China to Vietnam, not to Arkansas or Alabama (the U.S. states with the most Germanic syllabus---just to accommodate German Big Companies in Alabama).

The second big change is a gradual but unmistakable shift from trade in goods to trade in services. Manufacturing’s share of total output is falling almost everywhere, and the drop has been particularly sharp in China. Unsurprisingly, trade in manufactures is declining as a share of global GDP. Services will likely make up the slack, but trade in services is hampered by all kinds of political, regulatory, and cultural barriers.

There is no need for customers to speak the same language as the people who make their smartphones. But they are right to expect their doctor, architect, asset manager, or airline pilot to be able to communicate with them in a more-or-less comprehensible version of a shared language. And that takes time.

Yet, by forcing people to hold business meetings across a computer screen, the COVID-19 pandemic has given services trade an unexpected shot in the arm. Not surprising that the Gallup Economic Confidence index is deep under water. It had reached +45 before Covid hit, and is now at -45. France, with April elect Macron to be 2nd term Presidency, but days ago Le Pen Ultra-Right wing her party gain 80 seats (2017: only 8) maybe have less number confidence. The man who wanted to lead Europe will not even be able to lead France.

Why not use similar technology to sell services around the world? Radiologists in Bengaluru were already reviewing X-rays produced in Detroit or Dortmund-Rhine-Westphalia before the pandemic. Now architects in Taipei design housing projects for Turin, and programmers in Tallin write code for firms in Toronto.

The economist Richard Baldwin has described globalization as a sequence of “great unbundlings.” The first occurred in the late nineteenth century when steam power cut the expense of moving goods internationally. The second came in the late twentieth century when information technology radically lowered the cost of moving ideas across borders. A third great unbundling beckons, predicts Baldwin, as digital technology makes it cheap and easy to move people across borders – without making them leave their bedroom or kitchen.

The final change is political. Politicians must understand that our economy grows faster when the 'gales of creative destruction,' involving the risk-taking of entrepreneurs, are allowed to overwhelm the visions of central planners. Until now, globalization has largely shaped governments’ policy options. Today’s policymakers rightly want to shape the paths that globalization follows. International flows of hot money can be destabilizing and need to be regulated (as even the International Monetary Fund now recognizes). Similarly, the direction of technological change is not preordained; as Harvard’s Dani Rodrik and Stefanie Stantcheva have argued, it can be shifted to create jobs rather than destroy them.

A growing number of essential global public goods – from climate control to pandemic relief – also call for more activist policies. If governments get it right, a more subdued, but also more sustainable and longer-lasting kind of globalization will emerge. Peddlers of deglobalization theories may then need to change jobs and re-skill. Fortunately for them, that is easier to do in an open and growing world economy.