A judge in Delaware Superior Court is expected to swear in the jury as soon as Monday in a defamation trial that has little precedent in American law. Fox News, one of the most powerful and profitable media companies, will defend itself against extensive evidence suggesting it told its audience a story of conspiracy and fraud in the 2020 election it knew wasn’t true. (But) "Fox has made a late push to settle the dispute out of court, people familiar with the situation said Sunday."

Fox Corp general counsel Viet Dinh "has told colleagues privately that he believes Fox's odds at the Supreme Court would be good."

The jury will be asked to weigh lofty questions about the limits of the First Amendment and to consider imposing a huge financial penalty against Fox. Some of the most influential names in conservative media — Rupert Murdoch, Sean Hannity, Tucker Carlson — are expected to be called to testify. But there is another fundamental question the case raises: Will there be a price to pay for profiting from the spread of misinformation?

Few people have been held legally accountable for their roles in trying to delegitimize President Biden’s victory. Sidney Powell, a lawyer who was one of the biggest purveyors of conspiracy theories about Dominion Voting Systems, the company suing Fox for $1.6 billion, avoided disbarment in Texas after a judge dismissed a complaint against her in February.

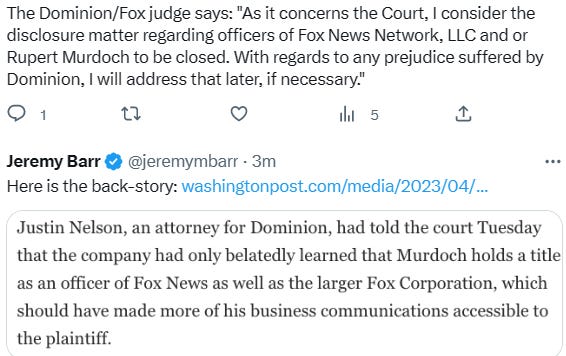

Fox has formally apologized to the judge in the Dominion defamation case, taking responsibility for the "misunderstanding" regarding Rupert Murdoch's role at the network that led the judge to launch an investigation into potential legal misconduct by Fox.

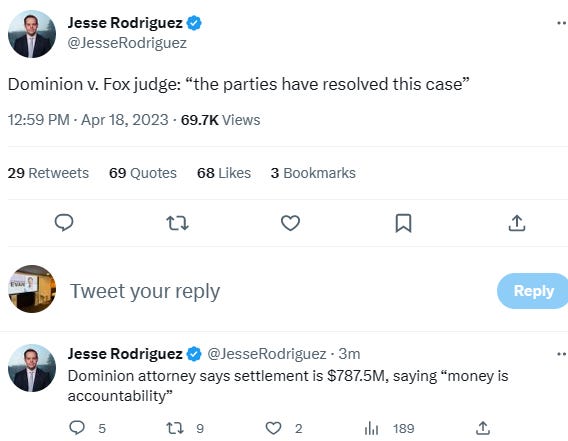

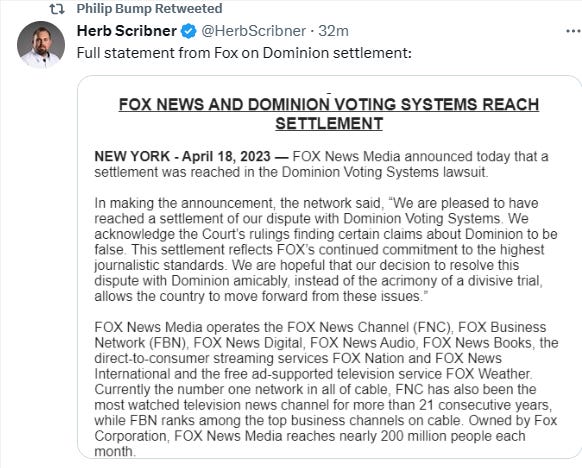

"Fox News apologized to the judge in the Dominion case, taking responsibility for the 'misunderstanding' regarding Rupert Murdoch’s role at the network that led the judge to launch an investigation into potential legal misconduct by Fox." Fox has already pursued settlement talks on multiple occasions. Dominion, knowing it has tremendous leverage, held firm. Many legal experts have wondered about the odds of a settlement hours before opening arguments.

Fox Corp shareholders are demanding company records that may show whether directors and executives properly oversaw Fox News' coverage of former President Donald Trump's election-rigging claims, sources told Reuters, in what could be a prelude to lawsuits seeking to make directors liable for costs.

Investors are using provisions in Delaware corporate law to demand internal Fox records to investigate how Fox's leaders acted as its Fox News network aired segments on Trump's false claims that he lost the 2020 presidential election due to voter fraud, two sources confirmed.

In moves not previously reported, shareholders are looking for records such as board minutes, emails and texts that may contain evidence that Fox directors and executives were derelict by allowing the network to air the false claims.

The shareholders could use these as well as evidence presented in other lawsuits to build a case for the leaders to be held personally liable for costs from two defamation cases by voting-machine companies over the Fox coverage.

The sources requested anonymity to discuss the demands, which are not public, and declined to provide further details. It was not clear how many Fox shareholders are pursuing information demands.

A spokesperson for Fox did not reply to a request for comment.

One individual shareholder has already sued Fox Corp Chairman Rupert Murdoch, his son and Chief Executive Lachlan Murdoch and three other directors, alleging they breached their duties to the company by allowing Fox to perpetuate Trump's false claims.

Two voting technology companies have sued Fox for defamation over its reports that their machines enabled voter fraud. They are seeking a combined $4.3 billion in damages, and costs related to the lawsuits helped increase Fox's expenses by $54 million in the second half of 2022.

The media company faces trial on Tuesday in Delaware on Dominion Voting Systems' claim that Fox defamed it. Dominion is seeking $1.6 billion in damages. Voting technology company Smartmatic USA filed a similar lawsuit in New York.

Documents made public in the Dominion case show top executives, including Rupert Murdoch, and producers and hosts discussed concerns about the network’s reputation and cast doubt on Trump’s claims of election fraud.

To prevail, Dominion must show that Fox knowingly spread false information or acted with reckless disregard for the truth - the legal standard of actual malice. Fox has argued that Dominion's case falls short of proving actual malice and its damages request is "untethered from reality."

If Dominion wins at trial, particularly if there is a large damages award, it will help shareholders argue the board should have put procedures in place to avoid airing defamatory claims that hurt Fox's credibility and finances.

If Fox prevails in the Dominion case, the shareholders' cases would not be as strong, said Ann Lipton, a professor at Tulane University Law School. But investors may still argue Fox leadership failed to prevent an "expensive and embarrassing" episode, she said.

Past shareholder derivative claims led to a $90 million settlement in 2017 over the Fox board's handling of sexual harassment at Fox News and a $139 million settlement by the board in 2013 over a phone hacking scandal at London tabloids, both funded by insurance policies.

Those settlements also led to added disclosure requirements.

Lipton said that investors suing over the 2020 election coverage could seek to create an independent panel to report to the board on news accuracy.

Abby Grossberg, the former Fox producer who claims the network pressured her to give false testimony, just escalated her own lawsuit against the company, adding CEO Suzanne Scott as defendant and accusing Fox's lawyers of deleting messages from her phone.

Jenna Ellis, an attorney who worked with Ms. Powell and the Trump campaign, received a reprimand last month instead of losing her license with the Colorado bar. Donald J. Trump, whose false insistence that he was cheated of victory incited a violent mob on Jan. 6, 2021, is running for president a third time and remains the clear front-runner for the Republican nomination.

Political misinformation has become so pervasive in part because there is little the government can do to stop it.

“Lying to American voters is not actually actionable,” said Andrew Weissmann, the former general counsel of the F.B.I. who was a senior member of the special counsel team under Robert S. Mueller that looked into Mr. Trump’s 2016 campaign.

It’s a quirk of American law that most lies — even ones that destabilize the nation, told by people with enormous power and reach — can’t be prosecuted. Charges can be brought only in limited circumstances, such as if a business executive lies to shareholders or an individual lies to the F.B.I. Politicians can be charged if they lie about a campaign contribution, which is the essence of the criminal case against Mr. Trump by the Manhattan district attorney’s office.

Fox News v. Dominion Voter Systems

Documents from a lawsuit filed by the voting machine maker Dominion against Fox News have shed light on the debate inside the network over false claims related to the 2020 election.

Running Fox: Emails that lawyers for Dominion have used to build their defamation case give a peek into how Rupert Murdoch shapes coverage at his news organizations.

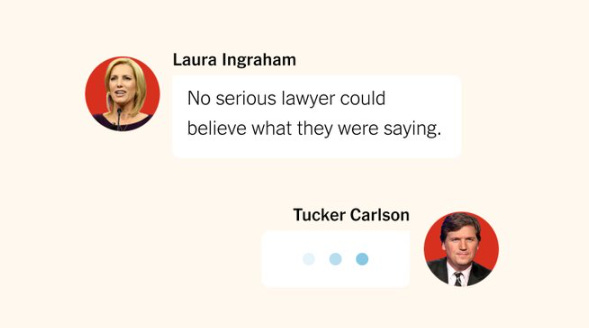

Behind the Curtain: Texts and emails released as part of the lawsuit show how Fox employees privately mocked election fraud claims made by Donald Trump, even as the network amplified them to appease viewers.

Tucker Carlson’s Contempt: The Fox host’s private comments, revealed in court documents, contrast sharply with his support of Trump on his show.

Attacks on Dominion: Despite the stark warning that Dominion has sent by filing several lawsuits, including the one against Fox, unfounded assertions about the company are still proliferating online.

In the Fox News case, the trial is going forward because the law allows companies like Dominion, and people, to seek damages if they can prove their reputations were harmed by lies.

The legal bar that a company like Dominion must meet to prove defamation is known as actual malice. And it is extremely difficult to prove because of the Supreme Court’s 1964 decision in New York Times Company v. Sullivan, which held that public officials can claim defamation only if they can prove that the defendants either knew that they were making a false statement or were reckless in deciding to publish the defamatory statement.

“There are all sorts of times you can lie with impunity, but here there’s an actual victim,” Mr. Weissmann added. “It’s only because of the serendipity that they actually attacked a company.”

Usually, there is great deference among media lawyers and First Amendment scholars toward the defendants in a libel case. They argue that the law is supposed to provide the media with breathing room to make mistakes, even serious ones, as long as they are not intentional.

But many legal scholars have said that they believed there was ample evidence to support Dominion’s case, in which they argue they were intentionally harmed by the lies broadcast by Fox, and that they would not only be surprised but disappointed if a jury didn’t find Fox liable for defamation.

“If this case goes the wrong way,” said John Culhane, professor of law at Delaware Law School at Widener University, “it’s clear from my perspective that would be a terrible mistake because this is about as strong as a case you’re going to get on defamation.” Mr. Culhane added that a Fox victory would only make it harder to rein in the kind of misinformation that’s rampant in pro-Trump media.

“I think it would embolden them even further,” he said.

This case has proved to be extraordinary on many levels, not only for its potential to deliver the kind of judgment that has so far eluded prosecutors like Mr. Weissmann, who have spent years pursuing Mr. Trump and his supporters who they believe bent the American democratic system to a breaking point.

“Even if this didn’t involve Donald Trump and Fox and the insurrection, this is a unique libel trial, full stop,” said David Logan, a professor of law at Roger Williams School of Law and an expert on defamation. “There’s never been one like this before.”

It is extremely rare for defamation cases to reach a jury. Mr. Logan said his research shows a steady decline over the years, with an average of 27 per year in the 1980s but only three in 2017.

Some experts like Mr. Logan believe the case’s significance could grow beyond its relevance to the current disinformation-plagued political climate. They see an opportunity for the Supreme Court to eventually take the case as a vehicle to revisit libel law and the “actual malice” standard. The justices have not done that since a 1989 case involving a losing candidate for municipal office in Ohio who successfully sued a newspaper after it published a false story about him a week before the election. The court said that a public figure cannot recover damages unless there was “clear and convincing proof” of actual malice.

The actual malice standard has been vital for individual journalists and media outlets who make mistakes — as long as they are honest mistakes. But some scholars like Mr. Logan — as well as two conservative Supreme Court justices, Neil M. Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas — have argued that “actual malice” should be reconsidered as too high a standard. Justice Thomas specifically cited as a reason “the proliferation of falsehoods.”

“The nature of this privilege goes to the heart of our democracy, particularly in this case,” said Mr. Logan, whose paper arguing that the courts have made it too difficult for victims of libel to win relief was cited in a dissent by Justice Gorsuch in 2021.

Fox lawyers are already preparing for an appeal — a sign they are under no illusion that beating Dominion’s case will be easy. At several recent hearings in front of Judge Eric M. Davis, Fox has been represented by Erin Murphy, an appellate lawyer with experience arguing cases before the Supreme Court.

Dominion also apparently considers the possibility of an appeal quite realistic. It had an appellate attorney of its own, Rodney A. Smolla, arguing on its behalf when questions of Fox’s First Amendment defense arose last month — the kind of constitutional questions that federal appellate courts will entertain.

The belief that the Supreme Court could eventually hear the Fox-Dominion case is shared by the general counsel of Fox Corporation, Viet Dinh. Mr. Dinh, who is likely to be called as a witness by Dominion during the trial, has told colleagues privately that he believes Fox’s odds at the Supreme Court would be good — certainly better than in front of a Delaware jury, according to people who know his thinking.

The evidence against Fox includes copious amounts of text messages and emails showing that producers, hosts and executives belittled the claims being made on air of hacked voting machines and conspiracy, details that Dominion has said prove the network defamed it.

But Fox lawyers and its public relations department have been making the case that its broadcasts were protected under the First Amendment because they encompassed the kind of coverage and commentary that media outlets have a right to do on official events of intense public interest.

“A free-flowing, robust American discourse depends on First Amendment protections for the press’ news gathering and reporting,” a network spokeswoman said in a written statement. The statement added that Fox viewers expected the kind of commentary that aired on the network after the election “just as they expect hyperbole, speculation and opinion from a newspaper’s op-ed section.”

Judge Davis has overruled Fox on some of its First Amendment claims, limiting its ability to argue certain points at trial, such as its contention that it did not endorse any false statements by the president and his allies but merely repeated them as it would any newsworthy statement.

A spokeswoman for Dominion expressed confidence, saying: “In the coming weeks, we will prove Fox spread lies causing enormous damage to Dominion. We look forward to trial.”

Inside Fox, from the corporate offices in Los Angeles to the news channel’s Manhattan headquarters, there is little optimism about the case. Several current and former employees said privately that few people at the company would be surprised to see a jury return a judgment against Fox.

Judge Davis has expressed considerable skepticism toward Fox in the courtroom. He issued a sanction against Fox last week when Dominion disclosed that the company had not revealed details about Mr. Murdoch’s involvement in Fox News’s affairs, ruling that Dominion had a right to conduct further depositions at Fox’s expense. In a letter to the judge on Friday, Fox said, “We understand the court’s concerns, apologize, and are committed to clear and full communication with the court moving forward.”

But the judge does not have the final say. Twelve men and women from Delaware will ultimately decide the case. And defamation suits so rarely prevail, it’s also reasonable to consider the possibility that Fox does win — and what a 2024 election looks like with an emboldened pro-Trump media.

After storm, the sun always shines.

Another (new) superstar regardless (costly) US$1.6 billion in America soil.

Writing the house biography of Tucker Carlson is the sort of challenge that could make even the most loyal News Corp. hand a little nervous. Carlson is Fox News’s franchise player, but he’s also a skilled political operator who has managed to keep both Donald Trump and Rupert Murdoch at bay.

So it made sense that talks are underway to give the lucrative, dicey assignment to one of Murdoch’s most trusted retainers: His new star columnist at the New York Post, Miranda Devine.

Devine, 61, isn’t standard-issue News Corp. talent. She’s not a newsreader plucked by Roger Ailes from local obscurity, or a former right-wing politician. She is, instead, a second-generation Murdoch loyalist who left Australia under controversial circumstances just four years ago, and has rapidly then become a major voice in American right-wing politics. Her right-wing politics and sharp news instincts for what readers want has endeared her to News Corp. readership, and bought instant credibility with the Fox News audience.

Devine’s rise may be as revealing about the heart of Murdoch’s media empire as anything he and his family say in careful testimony at their defamation trial in Delaware this week. Along with her personal loyalty — her late father Frank was a storied Kiwi journalist whom Murdoch brought to New York to edit his beloved Post in 1986 — she is a tabloid culture warrior in the old Anglo-Australian tradition, which has made her a good fit for America’s increasingly vitriolic news culture.

And, as the Dominion revelations have made clear of Fox’s leadership, when the chips are down, she doesn’t spend much time wringing her hands about Trumpian assaults on democracy. Instead, like Fox News, she’s defined by her enemies.

Some of Devine’s columns are conservative polemics — columns are a blend of conservative diatribes (prohibiting trans women from women’s sports is a “return to sanity”). Others simply fawn over Trump, “pitbull fighting for America.”

But Devine is often on the attack, and it’s her unrelenting focus on Joe Biden’s son Hunter’s business relationships (and personal vices) that truly established her conservative bona fides to Post readers and Fox News viewers.

Devine has stood out from her peers by lacing her pieces with elements of hard news, increasingly breaking tidbits feeding conservative media news cycles.

Over the past several months, she published leaked documents from the House Oversight Committee’s investigation into Hunter Biden’s business dealings, and developed law enforcement sources who helped her break the news about a gang that had preyed upon gay men in Hell’s Kitchen.

Former Trump administration official Kash Patel passed her the scoop that he was suing Politico for defamation, and the Trump campaign gave her the exclusive on an FEC complaint complaining about a letter from intelligence officials in 2020 labeling Hunter’s laptop as disinformation.

The columns and exclusive stories have made her a regular on Fox News, where she’s a contributor and a frequent guest on Carlson’s prime-time show. And her recent book “Laptop From Hell,” a deep-dive into Hunter Biden’s laptop, has become one of the best-selling conservative books of the past year.

Rep. James Comer, who is leading House Republican investigations into Hunter’s business relationships, said in a statement that Devine is a “top-notch reporter who continues to reveal the full extent of the Biden family’s influence peddling schemes and shady business dealings overseas.”

In the leadup to the 2020 presidential election, then-New York Post editor Col Allan wanted to spice up the Post’s editorial page. So he recruited Devine for a year and a half-long stint covering the election.

It was a homecoming for Devine, who was born in the US. She’d traveled to the country with her father, and studied journalism at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism before becoming a newspaper reporter in Sydney.

But in her decades in Australian journalism, Devine developed her own distinct reputation as the ideal News Corp. right wing columnist with a Catholic bent. She aggressively defended Cardinal Pell, who was charged and later acquitted of child abuse allegations, but helped craft the Catholic church’s response to other allegations of child abuse. Devine defended a rugby player who called another player gay during a match, writing that “the word has changed meaning over the last decade. Young people use ‘gay’ to mean lame or dumb or stupid, as in ‘That’s so gay.’”

On that subject, she was a vocal opponent of gay marriage, so vocal that a heated dispute over the issue with the CEO of an airline threatened to derail Lachlan Murdoch’s Christmas party, and required the CEO of News Corp. Australia to intervene.

Her views and her sensational reporting made her one of the most well-known Australian conservative columnists, and a favorite of the Murdochs’.

While liked by many of her colleagues, Devine also had a mean streak. She apologized to a professional rugby player for mocking his sign language to a deaf friend during a match.

Most notoriously, she speculated in 2020 that a video of a weeping indigenous nine-year-old with dwarfism was not the result of bullying, as his distraught mother claimed, but a “scam.”

After the family sued her for defamation in 2020, Devine apologized and paid $200,000 to the family.

Devine’s scandals garnered national attention back home. And some of the errors in her reporting in the US were equally egregious: While it was fixed in subsequent versions, the first print edition of Laptop From Hell had a glaring error. Devine mistakenly wrote that Ashley Biden, Joe and Jill Biden’s daughter, was killed in a car crash.

But these didn’t seem to bother higher ups at News Corp. in the US, where her stock was rising. She had become a favorite of Donald Trump’s after complimenting his “bravery” in overcoming Covid-19 while in office. (Trump thanked her by tweeting out her New York Post email address.)

After the 2020 election concluded, Devine was prepared to head home. But News Corp. put on the full court press for her to stay: One New York Post source said that higher ups begged Devine to remain in her role as a columnist. Murdoch emailed Fox News President Suzanne Scott that December, asking her to sweeten the deal: “People are trying to steal Miranda Devine. would be great if you signed her as a contributor.” Scott promised to “work on this,” and Devine quickly became a contributor for the network.

Devine has settled into a comfortable role at the Post, breaking stories on the news team, while writing conservative red meat on the opinion side. She remains primarily edited by print editor in chief Keith Poole personally, the result of the increased levels of scrutiny she receives, and her history of notable factual errors. And while she has been known to miss the print deadline, forcing the post to run house ads in the first print edition, another source said she’s a traffic-getter for the paper’s website.

In an email, Devine did not respond to inquiries about some of the more controversial elements of her career, including the defamation settlement in 2020, or errors in her reporting.

But she defended her reporting on Biden, saying that even Hunter’s team is reading and interacting with her reporting.

“They used not to respond but I have been in regular contact now for almost a year,” she said. “Still hoping for an interview with Hunter.”

ROOM FOR DISAGREEMENT

Devine offers a clear and unfiltered look from inside the Trump movement, something many American publications have struggled to provide. “ Everybody is out there looking for the decent pro-Trump columnist, because we all feel responsible for doing it,” the Washington Post’s deputy editorial page editor, Ruth Marcus, said in 2017. “You know, we can’t force you to read it, but we have to offer it up to you.”

NOTABLE

Devine remains a controversial figure in Australia, where she was admonished by the country’s press council for a story she wrote with inaccurate claims about trans adolescents. She made national headlines back home when she told Fox News in 2020 that it was “incredibly selfish of older people” to be “timid and afraid” of the coronavirus pandemic.

But her columns carry some heft in certain Australian political circles. A 2016 story she wrote about a teacher at Sydney school who suggested students use gender neutral language prompted an investigation from an education minister (as well as pushback on the veracity of the report from the school).

Another superstar under “Murdoch’s Empire” and not linkage with Fox, but “another Tucker” in (again) “Murdoch’s Empire”: Emma Tucker

Emma Tucker got her first inkling that something bad might be happening on the afternoon of March 29.

Two months into her job as editor-in-chief of The Wall Street Journal, she was having a business-as-usual meeting with Liz Harris, her managing editor. Harris, an Australian, had followed Tucker to New York from the also–owned–by–Rupert Murdoch Sunday Times of London. Harris mentioned, almost as an aside, that a 31-year-old foreign correspondent named Evan Gershkovich had missed his daily check-in. The last time he’d been heard from, he had just arrived at a steakhouse in Yekaterinburg, Russia, to meet a source. Not to worry; these things sometimes happen.

Tucker, 56, paused and thought for a moment. She had been introduced to hundreds of people since Murdoch announced in December that he was giving her the Journal job. Before she arrived in New York, she’d passed through the Journal’s London bureau and met a procession of foreign correspondents stationed there. Ah yes, Evan. He had left Moscow after the invasion of Ukraine, but within a few months, he’d returned to do reporting, filing vivid, on-the-ground stories about the human, economic, and social costs of the war. She remembered.

Harris assured her boss she would keep her posted, and they went back to work. But Tucker had trouble focusing. She kept thinking back to 2014, when she was deputy editor at the Times of London and two of the paper’s journalists were kidnapped in northern Syria. The pair managed to escape but not before one was shot in the leg. Tucker met with them and their families when they got home. Ever after, her approach with foreign correspondents was cautious. She would order them back from danger zones, sometimes against their own wishes. She had learned what it was like to face the anguished family of a reporter. She tried to push those dark thoughts from her mind.

At about 6 p.m., she looked up from her desk and noticed Harris moving hurriedly toward her. She could tell from the way her No. 2 was walking that something had gone horribly wrong. Gershkovich still hadn’t checked in, Harris told her, and there were local reports that a man had been arrested in a restaurant.

In Russia, a driver was sent to the reporter’s home. Nobody was there. Night fell in New York, and Tucker returned to her new apartment on the Upper West Side — her three sons still live in the U.K., and her husband has been to-ing and fro-ing — to drift off to an uneasy sleep. At 4 a.m., her phone rang. It was Harris. The successor agency to the KGB, the FSB, had Gershkovich and was accusing him of spying. Tucker got on a call with the Journal ’s security team, an attorney, and the foreign editor. At 5:11 a.m., she emailed a note to her new staff.

Soon, Tucker, who had never worked in America before and hardly knew her way around the city, let alone her own newsroom — her assistant hasn’t even moved from London yet — became the public face of Gershkovich’s imprisonment.

She appeared all over television, on everything from Face the Nation to Anderson Cooper 360° to Fox & Friends, to protest the Russian charges of espionage as “utter rubbish.” The Journal immediately profiled its reporter on the front page of the weekend paper, posted a selection of his coverage of Russia outside the paper’s paywall, and then published a piece about the infamous Lefortovo prison, where Gershkovich is being kept. Tucker and Harris visited the reporter’s family in Philadelphia on April 2 to deliver notes from their son’s friends and colleagues. Journal reporters, normally advised to be circumspect on social media, were instructed to tweet as much as possible about Gershkovich, and readers were encouraged to add #IStandWithEvan to their social-media posts.

Now, Tucker’s journalistic rivals have rallied around her. “She has handled a difficult situation with urgency and confidence,” says Joe Kahn, executive editor of the New York Times. “Emma has also done one of the most important things an editor can do in a terrible situation like this, using good journalism and a powerful platform to keep the injustice front and center in people’s minds.”

Which is really — even when you run one of the most powerful news organizations on the planet — all you can do. President Biden has spoken up in support, and it’s going to be up to Secretary of State Antony Blinken, who has already said “there is no doubt that he is being wrongfully detained,” to negotiate his release. The assumption is that the Russians are planning on convicting him secretly so they can use him for a prisoner swap.

Tucker’s job is just to keep him in the news. “You really have to think how to keep high and sustained visibility,” says Fred Ryan, the publisher of the Washington Post. He’d started in his job just weeks after reporter Jason Rezaian had been imprisoned in Iran in 2014. “There’s a fire hose of things coming at the White House and particularly the president,” he says. “Things quickly get deprioritized because there’s always something new.” The Post’s then-editor, Marty Baron, had to become the public face of Rezaian’s imprisonment. “My role,” says Baron, “was really to be a regular presence at key moments on television, on radio, and other interviews with the printed press, to be the person who was always talking about Jason and articulating what was going on and the injustices that were being inflicted upon him.” Baron had encouraged continuing attention from other media outlets and confronted Iranian officials when possible, including Hassan Rouhani at his annual meeting with the press prior to the U.N. General Assembly.

For a new editor in a strange land, it’s a challenge. The Journal staff had been wary of Tucker, and for good reason. Her predecessor was Matt Murray, a Journal lifer who had been given the top job in 2018 after the staff rebelled against the previous Murdoch import as editor, Gerard Baker. Baker was a bumptious right-winger who’d been accused of slanting the coverage toward Trump. So the worry with Tucker, as one reporter puts it, “was, like, ‘Are you Gerry or a reasonable person?’”

After all, Murdoch chose them both. As he opaquely wrote back when I asked why he picked her, “Emma Tucker will build on The Wall Street Journal’s authority and give it new life, as she did with The Sunday Times in London.”

What he wants from her is one of many open questions in Murdoch world. There is the coming defamation suit against Fox News by Dominion (the trial is set to start April 17, but embarrassing revelations have been dribbling out for months). His plan to remerge the two halves of his empire — the wildly profitable TV part and the legacy newspaper business — ran aground in January. And last month, the 92-year-old got engaged to be married for a fifth time, but by April it was off. Questions of succession and the entire future of his imperium swirl.

Inside the newsroom of the Journal, which remains Murdoch’s prize possession, staff are learning who it is he has foisted upon them now and what her plans are for the august broadsheet as Tucker faces the most intense crucible imaginable for an editor. Although, as Baron points out, “this is probably something that could help her win trust with the staff, to show that she is totally committed to Evan’s release.”

Emma Tucker keeps Evan Gershkovich in the news.

People who know Tucker will remark that this is not, technically, the first time she has lived in America. But it has been a while.

She grew up middle class in the town of Lewes, south of London. Her father was a lecturer in child psychology at the University of Sussex, and her mother had been a teacher. When she was 16, as she recounted on a 2018 podcast called Media Masters, she “saw an advert for a school” in New Mexico called the Armand Hammer United World College of the American West. “I set off with two other British girls aged 15 — no, we were 16, we did our O-levels — to this school, literally in the middle of nowhere.” It was a formative adventure.

In 1986, she arrived at Oxford. “It was still quite a male atmosphere,” says Stewart Wood, a Labour Party politician and former adviser to Prime Minister Gordon Brown who befriended her there, “but she was not at all intimidated by that.” When the captain of the rugby team barged naked into her room one night, she felt the school didn’t take the intrusion seriously, so she wrote about the incident for the Guardian.

“That was the beginning for her,” says Rachel Johnson, a British journalist and the sister of former prime minister Boris Johnson. It became clear Tucker was going to be a writer; she edited a college magazine titled The Isis.

Although not a member of the British elite by birth, she stood out. “She’s one of my oldest and best friends,” Johnson says. “She’s my daughter’s godmother, and I’ve known her since we were at Oxford together. We were all younger then. She’s a woman of stature and maturity now, but I wouldn’t have said either of us were particularly grounded. But she was always good fun, absolutely full of energy and just adorable in every way, really. There was a place called the Dub Club, the Caribbean club. We used to go there, and we all wore the same clothes. We wore jeans and black roll necks. We thought we were cool.”

Each year, the Financial Times would take on two graduate trainees; in 1989, Johnson became one of them, and Tucker followed in 1990. “We just had a blast because there were very few women on the paper,” remembers Johnson. “I mean, like, four. It was me and Emma against the rest. She was always much more diligent, I think, and applied than I was. Stayed there longer, got sent abroad, had three kids.” (Tucker also has three stepsons with her second husband.)

Tucker became an economics reporter at the FT in the early ’90s, just as the U.K. was being booted from something called the European Exchange Rate Mechanism — basically the system that preceded the euro, which Britain ultimately never took up — sending shock waves through the economy. It was a complicated story to cover, which made for good training for her next job: She moved to Brussels to report on the minutiae of the European single market. “She persevered with a lot of grit and determination to get to the top,” remembers her then-boss, Lionel Barber, who went on to be the editor-in-chief of the FT. “She can be very charming, and she’s got a good sense of humor. She recognizes the absurd — often when I’ve been absurd — and she’s good at poking and pricking pomposity.”

She soon struck up a friendship with the mischievous foreign editor, an Aussie named Robert Thomson who dressed a bit like a teddy boy and had an eye for quirky stories. He became the weekend editor, and young Tucker filed colorful feature stories to him about subjects like polyglottal “Eurobrats.” (Tucker speaks French, German, and Spanish.)

He was a good friend to have. Thomson ascended at the FT, becoming the U.S. managing editor in 1998. While living in New York, he’d gotten to know fellow antipodean Murdoch, and when he was passed over for the top job at the FT in 2001, he defected to the Times of London. Murdoch and Thomson famously get on well. They share a birthday, and The New Yorker’s Ken Auletta once wrote that “he is perhaps Murdoch’s only close friend.”

The Times, founded in 1785, was the original crowbar Murdoch used to pry his way into the London Establishment. He’d bought the center-right paper and its weekend edition, the Sunday Times (which, in common English fashion, has always been run like a separate paper with its own editor and staff) back in 1981, when he was just 49.

In 2007, after Murdoch vastly overpaid for The Wall Street Journal in order to force his way into the American Establishment, he brought Thomson over as its publisher, then its editor. But before he left London, Thomson had lured Tucker away from the FT to the Times.

By 2013, she was No. 2 at that paper, working under then-editor John Witherow. Wood, the Labour politician who knew Tucker from university, remembers visiting the newsroom then and describes their relationship: “Witherow was, and is, someone who has a reputation of being quite, what’s the word, dictatorial. You had all these people scuttling and asking for his view on quite detailed things they clearly had a grip on. He was also a taciturn guy. He quite kept to himself.” Tucker, says Wood, “was, style-wise, quite different to that in the sense that she talks a lot, likes to get people in, likes to ask them what they’re thinking. The energy she wears on her sleeve quite strongly, and if she has worries, she’ll express them. She’s almost the opposite, character-wise, to him.”

In 2020, she became editor of the Sunday Times. She was the first woman to have the job since 1901, when the paper was edited (and owned) by Rachel Beer, a member of the fabulously wealthy Sassoon merchant family.

Many on Fleet Street marvel at Tucker’s ability to rise in Murdoch world seemingly without compromising her beliefs. “If you’re looking at the political spectrum at the top of News Corp., Emma is not a natural fit there,” says Barber. Witherow describes her as “more a metropolitan liberal.” Wood says, “She’s never hidden that, and yet she’s thrived under Rupert Murdoch at a time when the conservative government had been in power for a long time, and Murdoch had been pretty clear that he supports, broadly speaking, the Conservatives.”

Tucker was, among other metropolitan things, anti-Brexit. She also recognized that the future of the Times of London was in creating a “quality journalism” brand and hiding it behind a paywall. As she said in that 2018 podcast interview, “We made a very conscious decision not to compete on breaking news but to focus on what we’re really good at. What are we really good at? News, comment, analysis, big reads, features, advice.”

That was the strategy she took with her to the Sunday paper. “The paper had been run forever by a bunch of old-fashioned print people, and Emma was brought in with a real mandate to totally overhaul the place,” recalls one former Sunday Times colleague. “She basically said, ‘Welcome to the digital revolution.’ She hired a bunch of younger faces, promoted younger people.” Out went the “pompous old men” with their “misty-eyed tales about the glory days of Fleet Street, when they were just printing money and drinking gin in the afternoons. She would say, ‘Now we actually have to work for people’s attention.’” She wore sneakers to the office, always kept an open door, and made the news meetings an exciting place to be.

The paper had to play to its upmarket subscriber base, but it also had to stay true to its Murdoch DNA. Tucker seemed to achieve the balance well. “I had been terrified when she came in that this might be some new expression of wokery being foisted upon the Sunday Times,” says Rod Liddle, the paper’s right-wing columnist-provocateur, “but we went out for lunch quite early on and she had a sense of humor.” Perhaps she was just adapting to her Murdochian environs? “I don’t think she’s a chameleon,” says Liddle, “’cause she would argue with me about stuff. I think she is of the liberal left but is not remotely doctrinaire about it.”

“She’s had to put up with a lot of prejudice and obstacles as a woman journalist in Britain,” says her former boss Barber. But “she’s very good at handling men and getting what she needs done,” says the Sunday Times colleague in what came to be a frequent refrain on many of my calls for this article. “Yes, I think she is very good at managing men,” says Rachel Johnson. “She’s a fantastic woman,” attests Witherow.

When she was asked about newspapering being an old boys’ club by Media Masters, she seemed to shrug it off: “I don’t think there are obstacles to women getting on. I mean the issue for British newspapers I don’t think is so much women; it’s that we’re not very diverse — and that’s much more of a challenge, frankly, than whether or not women are getting promoted.”

Meanwhile, her revamped paper had its share of agenda-setting scoops. The Sunday Times had been a big Boris booster, but after Tucker took over, the paper’s investigative desk — the “Insight” team, as it’s known — dug into Johnson’s shambolic handling of the pandemic. The resulting 5,000-word exposé, headlined “38 Days When Britain Sleepwalked Into Disaster,” went off like a bomb on Downing Street. I asked Boris’s sister, Rachel, if it ever got tense when her brother was being brought to the woodshed by her best mate, Emma. “We managed to keep that very separate,” says Johnson. “I can’t take any responsibility for anything she put in the paper. I have been blamed for it on occasion, but it’s never ever been anything to do with me.” (Although it presumably didn’t drive too much of a wedge between the two friends, considering she once described her brother’s rhetoric as “tasteless” and “totally reprehensible.”)

There have been other scoops. Last year, the Sunday Times broke the story of how the future King Charles III accepted a suitcase with €1 million in cash from a Qatari politician.

It was about a year ago that Tucker began telling people that she sensed she was being groomed to edit the Journal.

The Journal is Murdoch’s most important paper. In 2007, he overpaid for it from the Bancrofts. (The haughty Pierces of the Murdoch-inspired show Succession are based, in part, on that family.) As with his purchase of the Times of London decades prior, the Journal gave him a respectability that paired nicely with the reach of Fox News (which he started in 1996) and the New York Post (which he purchased in 1976).

But the Journal ’s ability to set the nation’s news agenda the way the New York Times and Washington Post did — despite having larger circulations than both at the time — was hampered by its approach to coverage. It was the premiere chronicler of finance, stuffed with investor tips and hard-hitting reporting on corporate America, and had a deliberately antediluvian front page with illustrations and not photographs. All this dated from the era when it was the businessman’s second read. But, as a consequence, people didn’t tend to say, “Did you see the front page of the Journal today?”

The Journal had two other things going for it: a firmly right-wing opinion section that operated separately from the news pages and had its own fixations (see “Who Is Vincent Foster?”) and a paywall that readers were actually willing to pay for (maybe because it could be counted as a business expense), while the Gray Lady was still giving herself away for free online.

But Murdoch wanted his even-grayer lady to pop. “If I may be so bold as to say that in this country, newspapers have become monopolized,” he said to a roomful of Journal bureau chiefs shortly after he bought the paper, according to Sarah Ellison’s 2010 book War at the Wall Street Journal. “They’ve become — some of them have become pretty pretentious and suffer from a sort of tyranny of journalism schools so often run by failed editors.”

The paper’s editor Marcus Brauchli was reportedly paid $6.4 million in severance to get lost, and Murdoch installed Thomson. Photos and nonfinancial news arrived on the front page, the features and lifestyle sections were expanded, and soon Murdoch had what he’d always wanted: a national daily newspaper, if one that seemed, in many ways, rather like any other quality broadsheet anywhere else in the world. There was even, for a while, a local-news section called “Greater New York,” which seemed designed to troll the New York Times.

In 2013, when the Murdoch empire was split in two, Thomson became the CEO of News Corp., home to all the newspapers and book publishing. His deputy at the Journal, Baker, was bumped up as editor. He had followed a familiar path: Like Thomson (and Tucker), Baker worked at the FT through much of the ’90s before jumping to Murdoch’s Times.

The newsroom did not take to Baker, to put it mildly. He seemed to many a reporter the caricature of an out-of-touch British colonial administrator. He sent barking emails and dropped words like otiose in staff memos. And he was a right-wing ideologue with a penchant for vaguely sinister chalk-striped suits.

But the real trouble came during, and after, the 2016 election. He was a bit too openly smitten with Trump for many on his staff. He once joined his reporters for a meeting at the Trump White House, soon after which a transcript of the Oval Office meeting leaked showing how Baker had sucked up to Ivanka. (“It was nice to see you out in Southampton a couple weeks ago.”)

The New York Times and the Washington Post and several upstart digital news operations, many of which embraced the resistance, started picking off top talent. By 2018, things had become so untenable that Baker had to be deposed, moved over to the opinion page, and given a cranky column called “Free Expression,” in which he could bang on about the sorts of things that presumably Murdoch gets himself riled up about when he can’t sleep at night. (Recent headline: “Employers Need to Put the Squeeze on Woke Intolerance.”)

Baker was replaced as editor by Matt Murray. He wasn’t a Murdoch apparatchik but a Journal lifer and an American. It was a remarkable choice in some ways in its very banality. Murray was known as being meticulous and focused on keeping up standards.

The Journal got some of its mojo back and broke big scoops, such as the news of the Stormy Daniels hush-money payments (first reported in 2018) and the Facebook Files (2021). But Murray is not a Murdoch made man or, in some ways, a natural newsroom leader. “The Journal under Matt really became rather gentlemanly,” says one hotshot reporter there. “He was boring, risk averse, very temperamental, and he would weigh in on every story.” He was so detail oriented that he would reportedly line-edit stories on WSJ Noted, a magazine the paper started to appeal to young people, objecting to “jargon-y woke-isms” like “trans-phobia.”

It was a difficult time for newspapers, with the New York Times and the Washington Post struggling to respond appropriately even as Trump behaved in ways that were unprecedented. Black Lives Matter and its aftermath only upped the tensions between leadership and many more progressive members of their staffs, who would gather on Slack channels to complain, critique, and strategize (one at the Journal was called Newsroomies). Murray was determined not to let his sober newspaper become drunk with outrage. But it was difficult. “There was so much devotion to this notion that we were the only ones who played it straight,” says another Journal reporter, “that we would bend over backward often in the wrong way.”

Meanwhile, Murray found himself in a simmering beef with Almar Latour, another Journal veteran who reportedly was also up for the editor’s job in 2018. “They hate each other,” the New York Times’ Edmund Lee quoted a source saying in 2021. Murray and Latour reportedly undermined each other, and sources told the New York Times that Murray was unhappy when Latour was promoted to be the CEO of Dow Jones and publisher of the Journal in 2020. (The Journal denied the feud at the time.)

In any case, it wasn’t all that surprising that Murray wouldn’t last forever in the job. He was always going to be a bit too American J-school deep state for Murdoch, who likes his editors to be Brits or Aussies. Just pick up a copy of his other New York paper, the Post: Its editor-in-chief, Keith Poole, and top columnists — Douglas Murray, Piers Morgan, Miranda Devine — all have funny accents. When Tucker’s appointment was announced, News Corp. said Murray would take on a new role reporting to Thomson.

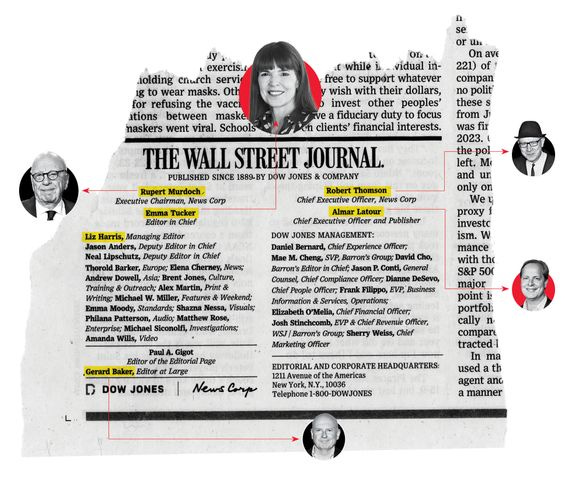

The WSJ Leadership: Rupert Murdoch, 92-year-old mogul facing challenges to his legacy names new editor of his fanciest toy. Emma Tucker, editor-in-chief. Robert Thomson, Rupert’s bestie and Emma’s champion, he’s a good ally to have in Murdoch world. Almar Latour, a journalist turned suit, he reportedly “hated” Emma’s predecessor, Matt Murray (not pictured). Liz Harris, Emma Tucker’s Aussie consigliere, one of three women she brought in from the Sunday Times. Gerard Baker, a Trumpy right-winger and ex-Journal editor-in-chief who was deposed in a reporter revolt. Now a cranky opinion columnist. Photo: Images: Getty

In February, Elon Musk joined Murdoch and his inner circle in a box at the Super Bowl. Tucker watched the game with Latour down in the stands. She asked many questions about how the peculiar American sport is played. A few weeks after that, she was in Washington, D.C., meeting with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy and attending the Gridiron dinner.

In some sense, Tucker is following in the tradition of nervy British editors before her who have splash-landed at the top of a New York publication and expected to sink or swim. “It can be quite a daunting pond with all its different power players and mores,” says expat Tina Brown, “which is why I wanted to give a party for her.” Brown and British ambassador Karen Pierce had organized a welcome gathering for Tucker in March. The guest list was larded with power brokers from the worlds of finance (Stephen Schwarzman, Jamie Dimon, Steve Rattner) and media (Gayle King, Jeff Zucker, Anna Wintour). But a few days beforehand, Tucker bailed on her big party.

Thomson had invited her to join him at the Morgan Stanley conference in San Francisco, and he is her boss, after all. “I think it’s a complex political situation at The Wall Street Journal,” muses Brown. “Everyone understands that Rupert is the great Logan Roy presence, as it were, stalking through the newsroom even when he isn’t stalking through the newsroom. And there’s Rebekah Brooks in London, who is always kind of an unknown force, and Robert here. So there’s quite a bit of trickiness.” (Brooks is the News Corp. executive who oversees the British papers; her career had very nearly been derailed by the phone-hacking scandal that came to a head in 2011.)

Tucker has always been a favorite of Thomson’s, who emailed me, via a News Corp. flack (it was, curiously enough, paired with the quote from Murdoch himself), that “Emma is a brilliant journalist and sage leader, and her excellence and efficacy will become obvious to all. She has taken the helm at a crucial time for media, with the looming challenge of Artificial Intelligence — her Actual Intelligence is even more potent.”

Tucker has brought with her from London three confidants. There’s Harris, the managing editor, and also Taneth Evans, an expert in digital strategy. But perhaps most crucially there is Jo Bull, her no-bullshit executive assistant who is the News Corp. whisperer, someone who can help Tucker navigate the competing power centers in the court of Murdoch. “She’s been in that world for ages and knows everyone and everything,” says one person at the Sunday Times.

Maybe it’s because Succession is back on HBO for one last season, or maybe it’s because the chess pieces really are still moving, but Murdochologists have been in overdrive lately. And soon the Dominion trial will start, which means Tucker will have to cover her boss and the Fox News people who share 1211 Sixth Avenue with her. Maybe it’s best not to read too much into it all. “Emma is much liked by Rupert,” says Brown, “so she has strength.”

There will be plenty else for the Journal to cover: Trump’s trial, a presidential election, a possible banking crisis, clashes with China, and, of course, war in Ukraine.

Tucker spent her first few weeks touring the newsroom and domestic bureaus. “It was kind of a speed-dating thing,” says one of the reporters, “and the editors were adorably nervous about showing off for her.” The staff there is still fixated, almost irresponsibly, on the internal politics of making it onto the print front page.

Tucker will, I’m told, now attempt to deprogram them all from such considerations. When reporters see their bosses squabble over print front-page placement, it sets a toxic top-down precedent about how and when things get pitched, reported, packaged, presented, and published. (This is why the New York Times did away with its “Page One” meetings years ago and the masthead editors there handed off print front-page decisions to a team of lower-ranking editors.) Tucker wants to deprioritize the dry, short, incremental news reports that make up much of the Journal’s daily output in favor of lengthy investigations, and she wants to cook up creative, conceptual stories that rely on the kind of expert business analysis that only a Journal reporter can provide. Ironically, this seems to be a return to the paper’s editorial identity under the Bancrofts, only digitized.

Two such recent stories that Tucker has pointed to as examples of what she wants include the investigation into who might have blown up the Nord Stream pipeline and a writerly report about how the collapse of Credit Suisse struck at Switzerland’s existential identity as a nation. Change is hard at the Journal, though. “She’s talking about doing big enterprise, impactful stories,” says one of the reporters, “but they’re also freezing newsroom travel. There’s worrisome creaks in the timber. We just don’t know, six months from now, will she be putting her own mark on the place? Or just responding to what changes you can make in the time you have? We just don’t know if she’s transformational or not.”

It’s a jittery time for everyone in the media business, and there are layoffs all over. Tucker’s contemporaries back in Britain say she must have been surprised when she first saw the size of the Journal’s budgets; she’s used to much smaller newsrooms and making do with a lot less.

But whatever changes she plans on making will have to wait. Right now, all anyone can think about is Gershkovich. “In pursuing Evan’s freedom, Emma is doing much that all can see and much, much more behind the complex curtain of global diplomacy,” Thomson wrote in the email to me. “Her savviness and empathy are vital at a time of high emotion and inevitable uncertainty.”

On April 6, the New York Times editorial board published a strongly worded call for Gershkovich’s release. The next day, Chuck Schumer and Mitch McConnell issued a rare joint statement demanding he be freed. A Moscow court is scheduled to hear an appeal on April 18 from Gershkovich’s lawyers, but, as the brother of Paul Whelan — another American currently being held by Russia — told Murdoch’s Post in early April, he worries it could be a “long, drawn-out process.” Whelan said Gershkovich’s charges were “identical” to his brother’s: “They’re concocted charges of espionage based on paranoia, rather than reality.”

And where is Rupert Murdoch? Under fire for, among other things, the Dominion lawsuit, he seems less the global power broker he once was, at least in public. He and Thomson are said to be working their connections around the world because you never know from where the breakthrough might come. But Tucker is the one out front.

Rezaian, the Washington Post reporter, was imprisoned in Iran for 544 days. “These are very tricky situations,” says his former editor Baron. “They likely go on for a long time. Almost never is there an instant release, or even a release within a short period of time. The Journal, both a new editor and the entire staff, has to be prepared for the long haul.”