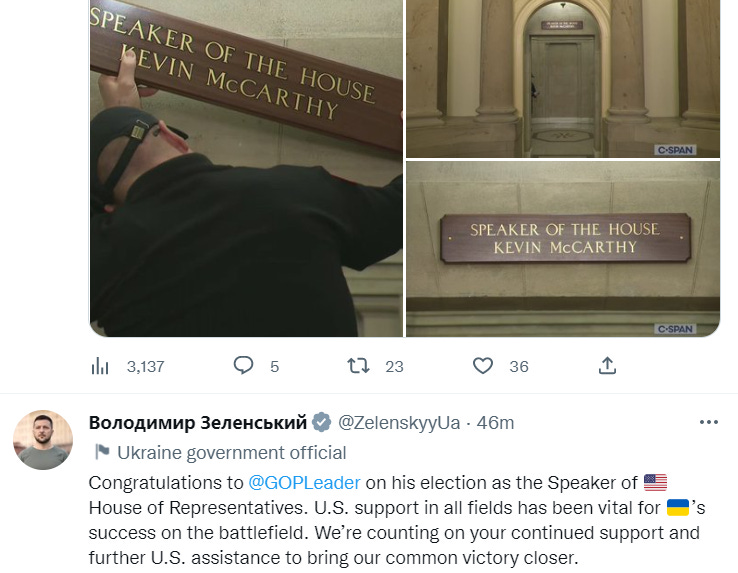

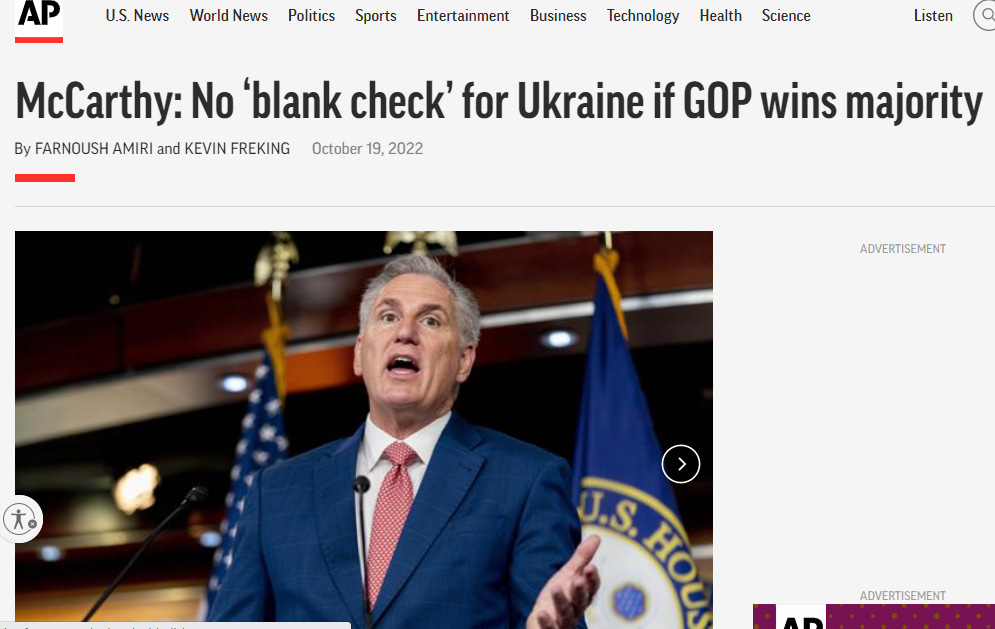

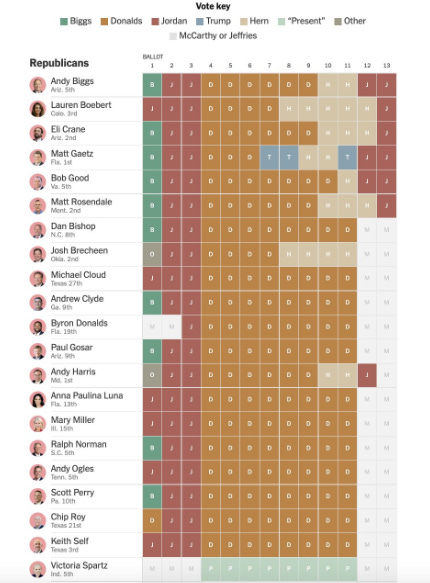

From the apparent chaos of the Republican party’s effort to select a speaker of the House there has emerged an opportunity to achieve a victory for a politics of moderation and constitutionalism. January 3rd, 2023 is the 16th anniversary of GOP Kevin Owen McCarthy being sworn into Congress. And today, he'll head to the House floor to try to become speaker (finally elected to be 55th House Speaker, Jan 7th 00.27 am, or after 45 hours & 57 minutes - 15th ballot).

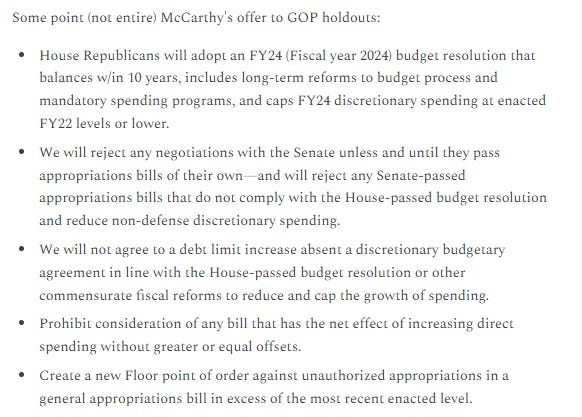

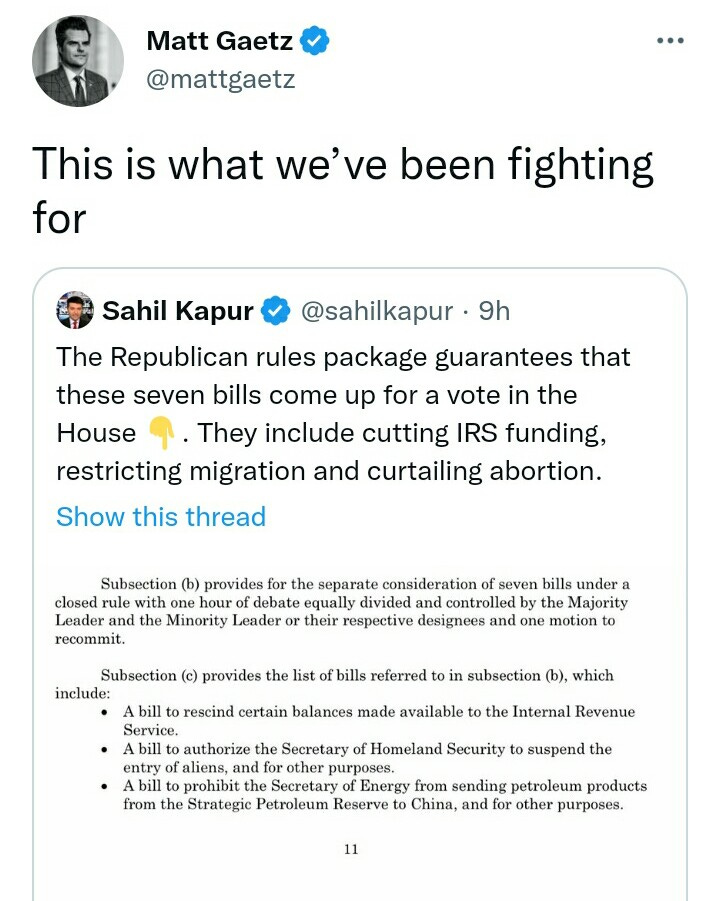

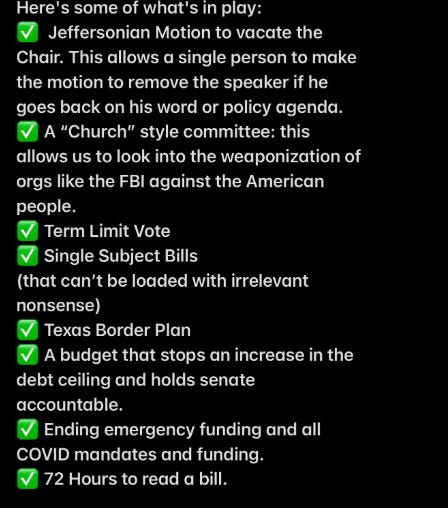

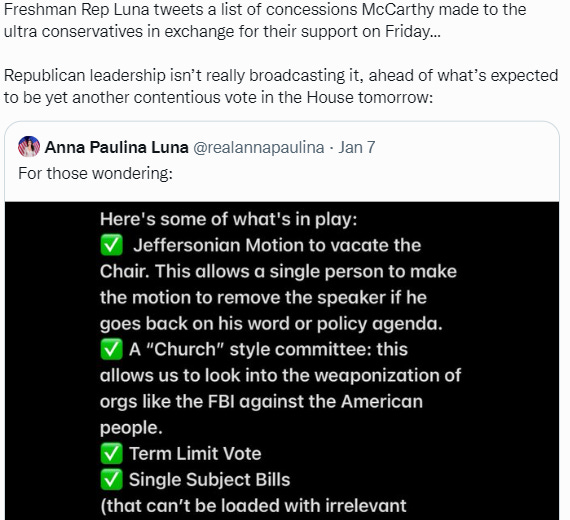

A faction of the House Republican conference is reportedly maneuvering to secure promises from Kevin McCarthy to enhance its political power, backed up by the threat of finding a leader even more compliant than the California congressman. Meanwhile, some Democrats see political advantage in the outsized influence that extreme members of the GOP will have in the selection of the next speaker, as it’s an opportunity to put GOP extremism on vivid display. Kevin has asked the House Freedom Caucus to present their offer to the House Republican Conference in a closed meeting this morning (Jan 3rd, 2023). McCarthy did not see the offer as viable. He ask help to Trump. He admit Trum help him to negotiate some GOP holdouts, especially Gaetz.

Noting again that the $1,500 monthly rent that (newest, 55th Speaker) McCarthy paid to Frank Luntz breaks down to $50/night, or exactly what Scott Pruitt paid to stay in that lobbyist's Capitol Hill house. A prominent evangelical lobbyist on Capitol Hill, whose firm wrote the legal brief cited by SCOTUS in the Dobbs v. Jackson decision that ended federal abortion rights, was caught on a hot mic saying she regularly prays with sitting Supreme Court justices. Investigators are looking into an allegation from at least one female Capitol staffer who believes a lobbyist used a date-rape drug on her during a meeting downtown. t's tough to move around Capitol Hill without tripping over a lobbyist who's trying to protect the fossil fuel industry.

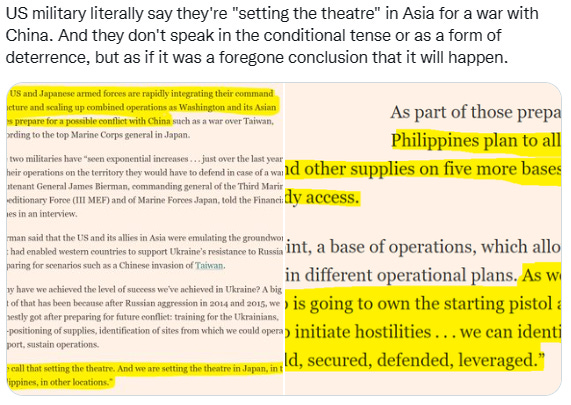

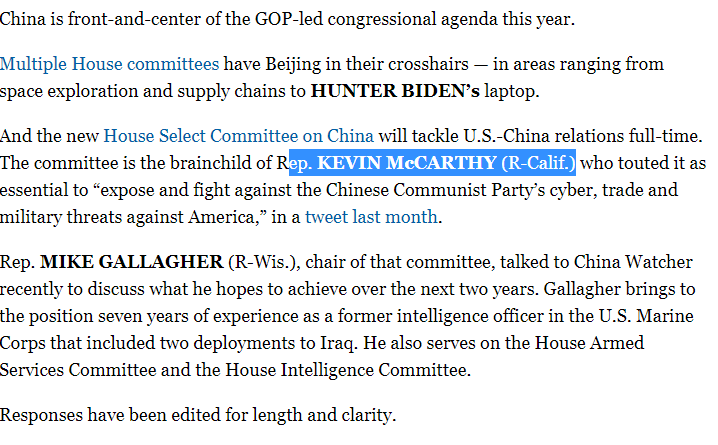

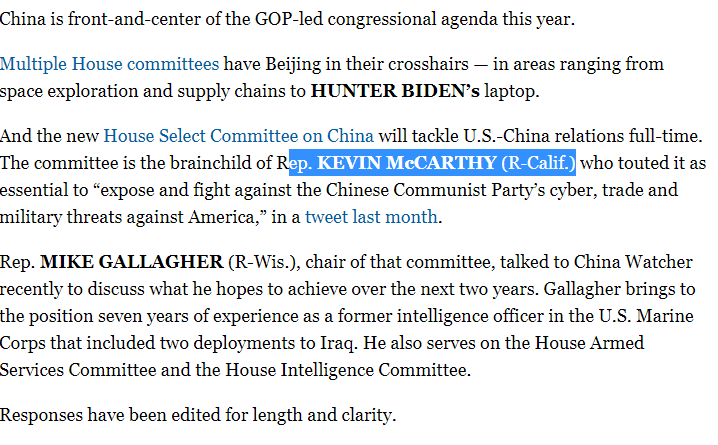

(Texas & China issue in Concession Kevin Owen McCarthy - Charles Eugene ‘Chip’ Roy):

Several US Congressman and Congresswomen regularly meet at the Capitol Hill Club with lobbyists from big pharma & global hedge funds who fund his or her campaign. GOP Scott Pruitt, 53, a former Oklahoma attorney general, stepped down as EPA administrator in 2018 amid a wave of ethics scandals, including living in a bargain-priced Capitol Hill condo tied to an energy lobbyist.

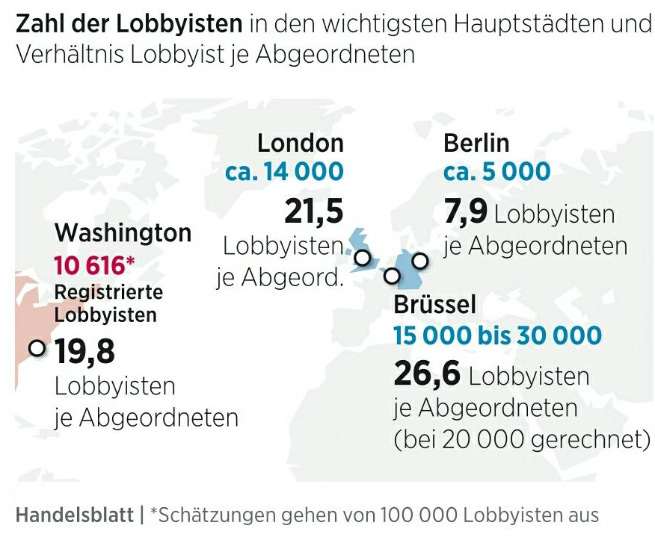

In the EU, Uber's top lobbyist in Brussels is out — just a couple of weeks after she had to represent the company in the heated Uber Files hearing. Her exit comes at a particularly inconvenient timing when lawmakers and EU member countries can't seem to make up their minds on a proposal that could reclassify millions of gig workers. Brussels (EU) tops Washington with 26,6 lobbyists per one member parliamentarian. London 2nd with 14.000 lobbyists or 21.5 per MP. Brussels struggles to deal w/ corruption scandal at European Parliament (now: Qatargate), remember, underhanded lobbying tactics are everywhere in Brussels. Example: lobbyist took his energy clients to heart of European Parliament under guise of being a journalist.

Those opposing anti-price gouging and profiteering bills were responsible for more than 2,600 lobbyist engagements on Capitol Hill. Supporters were responsible for fewer than 300 (*only 286), giving those opposed to anti-price gouging legislation a 9-to-1 advantage.

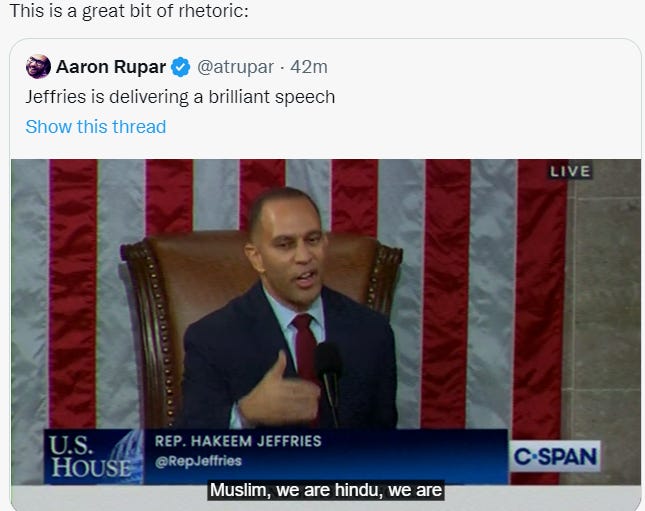

Back to the U.S. Other side in Democrat, George Kundanis will move from Pelosi to Hakeem Sekou Jeffries. Kundanis has been in House Democratic leadership since 1977. If you're a House Democrat, the 118th Congress literally could not be starting off better for you. After stepping up from Democrat House Leader, Nancy Patricia D’Alessandro Pelosi will be sworn in as a rank-and-file member of the House for the first time in two decades.

Since very few people watch congress as closely as some of us, this bears repeating. As of the middle of this morning, the house has no rules. So recessing after one or two speaker ballots requires either unanimous consent or a majority vote. Doing anything requires a majority. Now that (Democrat) & (Republican)INOs have taken care of the lobbyist debt (pork) & 3 letter agency rewards, the handful of America First lawmakers in Congress can focus on exposing more nefarious activity. Congress, where lobbyist donations are not bribes, and use of insider information for pecuniary gain is morally acceptable.

These dynamics have each faction and each party looking out for their own interests. But is there a path forward that would be better for the nation as a whole? Out of this political chaos could there be hope for a kind of constitutional restoration?

The speaker is supposed, at least some of the time, to speak institutionally for the whole House of Representatives, which in turn represents the whole nation.

(Before 14th round voting)

It’s true that in modern practice the speaker is most often little more than the leader of the majority party in the House. But the speaker is not supposed to be merely a party leader. The role of speaker is different from that of majority leader. One sees this in the fact that the speaker is an officer of the whole House not of one political party.

Back to Brussels. Any Brussels lobbyist worth an expense account knows how to shape EU legislation even after it is passed. But the European Parliament’s growing assertion of oversight powers over such tweaking is putting a higher premium on this skill, known in EU jargon as “comitology.”

No matter how much eye-rolling, confusion and derision the EU’s “c-word” inspires, it is in this final stage of the legislative process that a battle royal for influence is fought. While the European Commission uses it to tinker and EU states see it as a last-minute chance to promote their interests, Parliament is clamping down on what it fears is a way to undo the substance of legislation.

Lobbyists are caught in the middle of this complex power struggle, which often stretches their resources, technical know-how, and patience. Since 2011, European Parliament has had oversight of two processes that allow the Commission to ensure the seamless application of approved legislation in EU countries: “delegated acts,” in which Parliament and the Council allow the Commission to add new rules or amend legislation to ensure that its implementation goes smoothly; and “implementing acts,” in which the Commission calls in EU member countries to fine-tune the legislation.

To stay in the game, lobbyists need to be part of the Commission’s review process and know what to expect when it comes time for Parliament to sign off on whatever changes have been made.

“I would argue that it adds another dimension to our work,” Isaksson said. “The devil is in the detail, as it always has been; but now more stakeholders realize this is a process where you can have a say, often on a very technical level, and actually influence the outcome.”

Behind the scenes, lobbyists — including business associations, NGOs and consultants — say they are baffled by a process that now requires them to lobby EU states, provide technical advice and have an unprecedented level of understanding of the implementation process.

European Parliament has had the power to scrutinize “delegated acts” and “implementing acts” since 2011, when reforms adopted by the Lisbon Treaty kicked in.

The changes required Parliament and the Council to “delegate” to the Commission the power to make small fixes to legislation to ensure it stands up across all 28 EU countries. That gave the Commission considerable power to mold the legislation, as highlighted by a recent controversy over the implementation of EU tobacco regulations.

Both Parliament and Council can revoke that delegated power and reject the Commission’s final proposals — what MEPs refer to as the “nuclear option” — but cannot modify them.

All sides agree that the growing prominence of delegated and implemented acts is transforming both the legislative process and the lobbying industry around it.

But there is little agreement on whether this transformation has been good or bad in terms of accountability of the legislative process and whether Parliament stands to win or lose from it.

Commission is expected to publish a public register of all the national experts it calls on for delegated acts and technical committees — a move that would please lobbyists, who fear their efforts may be undermined when national interests are brought to bear behind closed doors.

The Commission’s “Better Regulation” reforms will also have an impact on the comitology process. They include a new procedure that would throw any changes made in the implementation of legislation open to public scrutiny.

These reforms would also slow the process down, something many observers say would defeat the purpose of comitology, which is supposed to be about last-minute tweaks to legislation to help with the implementation, not a chance to re-open a legislative Pandora’s box.

In this substack, we look back, several Lobbyists, and even this MP / Congress itself, playing a role in lobbying, focused in DC (Capitol Hill) and Brussels (EU Parliament, including lobbyists from the UK – before UK divorce from EU). How big his or her roles.

============

Facebook’s top EU lobbyist sends Brussels a friend request. Aura Salla has the task of convincing the skeptics they are wrong about the social media giant.

To get her way in Brussels, Facebook’s EU lobbyist-in-chief Aura Salla uses one of the tools she's been hired to promote: Instagram.

Between stills of Helsinki's waterfront and self-portraits on a yoga mat, Salla posted a lengthy, if cryptic, note on the day the European Commission published its landmark bills to rein in hate speech online and promote fair competition in the digital industry.

"We believe [the proposals] are on the right track to help preserve what is good about the internet," she wrote under a photograph of herself from her engagement photoshoot.

Salla’s approach pairs her business-friendly, center-right politics with a youthful — at 36, millennial — approach to social media.

Her employer has bet big on this hybrid, personal approach. Facebook is grappling with two major challenges in the European sphere: repairing a reputation that has been damaged by multiple scandals, and convincing skeptical European policymakers that they should go easy that same company.

The stakes could hardly be higher. Europe is one of Facebook’s most important markets, and it is also where the company is facing the toughest rules over how it polices its platforms. Following multiple scandals over user data, disinformation and hate speech, the social media giant is seen by many in Brussels as a bad actor.

Salla, a two-time European election candidate who joined Facebook in May, has the difficult task of convincing the skeptics they are wrong.

In December, the Commission unveiled the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act, two pieces of legislation that will create sweeping new rules and responsibilities for large platforms — especially Facebook — to ensure they compete fairly and remove harmful online content.

In 2021, the European Parliament and the Council of the EU will start negotiating a final compromise on the laws. Facebook has a lot riding on what the final version of the bills might look like.

To make sure they work for Facebook, Salla has a battalion of lobbyists and one of Brussels’s fattest lobbying budgets. Facebook has drastically increased its influence spending in Brussels, quadrupling it to more than €4 million since 2016.

Salla said Facebook's interest in the EU reflects growing awareness of the stakes among the company’s leadership. “Our leadership in California is very interested about the EU and EU affairs so [policies] are always a joint effort,” she said.

The former candidate credits her switch from politics to corporate lobbying to Nick Clegg — Facebook's chief lobbyist and a former politician himself, who was once a deputy prime minister in the U.K.

It's a role she says was tailor-made for her. “I always had this path for a more reasonable European Union. And I believe that I can do it also in this company. Because it's young, it's flexible, it’s dynamic, it’s controversial. It's facing challenges,” Salla said.

"Facing challenges" is one way to describe it. "Crisis-ridden" is another.

Working at Facebook means constantly putting out fires. In the U.S., several states are accusing the company of colluding with Google to consolidate their market power. In Europe, antitrust and data protection regulators are also investigating the social media company for how it collects and handles data.

Despite efforts to limit misinformation during the U.S. election, the company is also criticized for not doing enough to curb hate speech and conspiracy theories about the coronavirus.

That's partially because regulating content is something the platform has long resisted for fear of becoming an “arbiter of truth,” according to its CEO Mark Zuckerberg.

Despite the company's reputation, especially among Brussels policymakers, Salla believes the company's mission is good and that it wants to be better. “I would have never taken this role if I didn't believe in the goals and values that this company represents, and if I didn't believe that it's also willing to change where it's needed,” Salla said.

Where she differs from Nick Clegg is that she can pull off on social media what he can’t — dancing on Instagram reels, Facebook’s take on the short-video format popularized by Chinese video app TikTok.

Aura Salla completed a stint in the Finnish air force, a rarity for women.

Her gaze soon turned to Brussels. While many politicians treat European elections as an afterthought, Salla was always focused on Europe, said Antti Leino, her former campaign manager and friend. For Salla, the European Parliament was the “ultimate goal,” he said.

In 2014, despite a failed run for a European Parliament seat under the EPP banner, Salla found a way to Brussels. She was hired to work under her compatriot Jyrki Katainen, a commissioner at the time, before being scouted to join former President Juncker’s think tank, the European Political Strategy Center. She then moved on to the Commission’s advisory service, IDEA.

In 2019, she ran for Parliament again — and lost again.

Then Facebook called. It was a friend request she was happy to accept.

For Facebook, it makes sense to hire a Northern European pro-business, free trade advocate who is ideologically aligned with Facebook’s vision of a “free internet.” For Salla, it's a lucrative, high-profile job that puts her at the heart of Brussels' policymaking machine.

Salla’s new gig has also garnered criticism. Having moved straight from the Commission to a position lobbying her former employer, many see her new job as another example of the revolving door between EU institutions and big business.

According to Commission rules, former officials must ask for authorization before starting new jobs. The Commission can refuse such requests if the job could lead to a conflict of interest and is related to the official’s work in the past three years.

The Commission allowed Salla to accept the Facebook job on the condition that she not have any contact with IDEA on behalf of Facebook for the next six months, or lobby the Commission related to her work during the past three years.

But activists argue that's not enough. Corporate Europe Observatory, an advocacy group, criticized Salla for switching sides so quickly, and slammed the Commission's "ridiculous" conditions. “There is no way to enforce the prohibition against her using her insider knowledge and know-how to benefit her new employer,” the group said.

Salla points out that she was hired as a political adviser and that it was clear her Commission contract was temporary.

Facebook has a history of hiring from public office. The company’s biggest catch has been Clegg, but other officials include Salla’s predecessor Thomas Myrup Kristensen, a former official at the Danish Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation. His predecessor Erika Mann was a German MEP.

Clegg's legacy in British politics is now somewhat tainted — he presided over an historic collapse of the Liberal Democrats in the 2015 election following U-turn over university fees, and is unlikely to make a comeback anytime soon.

But Salla has not ruled out a return to politics in Finland, where "Facebook" isn't a dirty word.

“Aura Salla’s gig is a genuinely high-profile position for a Finn. Good that Finnish EU expertise is valued at American firms,” said newspaper editor Jussi Pullinen.

It helps that Finland is a tech-savvy, trade-friendly country removed from scandals like Cambridge Analytica that stained Facebook's reputation elsewhere.

Former campaign manager Antti Leino thinks Salla might pursue a political career later.

“If it’s the public sector, she wants to be a Commissioner or some other big, international political role,” Leino said. “Unless the private sector carries her away. That’s a possibility too,” he said.

Salla said changing job's hasn't affected her core outlook: “I'm still advocating free markets, I'm still advocating the single market of the EU.”

And she knows it's a tough gig. “People told me when I took this job, you know, it will be challenging, you will get so many challenging questions, and so on. I am ready for this. I have been defending a federal Europe.” Salla said.

============

It’s impossible not to think of the opening scene of

The Godfather when listening to some Brussels insiders describe the way top lobbyist Paul Adamson operates.

One seasoned campaigner remembers standing outside the Strasbourg chamber and watching MEPs queuing up to talk to Adamson. “That must be the ultimate accolade for a lobbyist,” he says: “While most of us spend our time knocking on members’ doors, they’re knocking on Adamson’s.” Another describes the loyalty Adamson’s young team of staffers show to their boss. “He stands outside the hemicycle, flicks his eyelids at an MEP and off his staff run like rabbits”, he says. An admiring colleague adds: “He won’t necessarily be the loudest voice but people listen to what he says.”

Adamson would probably be appalled by the Don Corleone analogy. For a start, he’s so self-effacing he makes Hugh Grant seem bumptious. Ask him about the millions of euro he pocketed from selling his company in 1998 and he blushes and struggles for words. “It gives you a quiet confidence,” he says before grumbling about how some people use the millionaire tag as a form of insult.

Another noticeable difference between Corleone and Adamson is that the latter sees no need for the ‘horse’s head’ tactics preferred by the mafia mobster. In fact, what is astonishing is that after two decades in the cutthroat world of consultancy it is hard to find anyone who has a bad word to say about the 47-year-old father of two – Tessa is 15 and William 12.

“He has an aura of being solid, respectable and trustworthy,” says one NGO head, using the type of adjectives not normally associated with the lobbying industry. Adamson admits that he is not a “typical in- your-face lobbyist,” adding: “I’m much more a behind-the-scenes player trying to get two sides to find a way forward.”

This image of the master-puppeteer pulling strings behind the public’s back is one that seems to elicit fear and loathing from some people and hushed respect from others. In an article entitled At whose service? left-wing writer Solomon Hughes links Adamson to UK premier Tony Blair and other New Labour luminaries in order to prove how the lobbyist uses friends in high places to push through a neo-liberal agenda.

For instance, this week he was schmoozing with UK Foreign Secretary Jack Straw at the opening of the Confederation of British Industry’s new Brussels office.

But it seems his main motivation in getting involved in party politics is not to make money – he already has enough of that – but to push the UK down a more pro-European path.

He sits on the board of ‘Britain in Europe’ – a group that promotes the joys of the single currency, and sponsors debates about Europe in London and Brussels. And this week he launched a glossy monthly magazine about European affairs, aimed at the UK market.

“Having spent 20 years here it exasperates me that the British are not more European or more aware of Europe,” he says, adding: “Europe is not just important, it is interesting and I refuse to believe there are not ways to make it more lively.”

Talking to Adamson, it is clear that his early years had a profound effect on both his personal and political development. Asked what makes a millionaire lobbyist a loyal Labour supporter, he replies: “It has a lot to do with my roots. When Blair says there’s no contradiction between being a successful businessman and having a social conscience, that’s exactly how I feel.”

Adamson’s introduction to lobbying came early when his publican father led a campaign to legalise Sunday boozing in North Wales, which was then mostly ‘dry’. Growing up in a pub also taught him how to mix with locals – speaking in Welsh – and earn his keep by cleaning crates, stacking shelves and pulling the pump.

When Adamson’s father died in his final year of school he knew it was time to fly the family nest. As part of his languages, politics and economics degree course he spent a year in Grenoble and immediately after graduating became the UK’s first student to enrol at the European University Institute in Florence. “There were no books on the shelves but a lot of famous professors queuing up to teach you,” he recalls.

Adamson came up with a thesis idea that predated the split in the UK Labour Party in the mid 1980s. It compared factionalism in the British and Italian centre-left and tried to find out why some members splinter off to form new parties and others stay around to make mischief – a subject Neil Kinnock knows a thing or

two about. “I tried hard to convince myself I’d be an academic,” says Adamson. In reality he was more interested in the French librarian who was later to become his wife; but his yearning for academic respectability still remains. He sponsors studies into subjects like the voting patterns of MEPs, writes for learned tracts such as the European Business Journal and bank-rolls think-tanks like the Campaign for European Reform.

At 25, Adamson might have been fluent in three languages and the holder of a double degree, but he was still “totally unemployable”. So after the European Parliament’s first direct elections, he wrote to all the new deputies asking for a job.

Although the young graduate was already a Labour supporter, the party was then in favour of pulling the UK out of the then EEC, so he ended up working in the London office of newly elected Conservative member Robert Jackson.

After two years as an MEPs’ sidekick, Adamson upped sticks to Brussels to join his French wife Denyse, who was working in the European Parliament as PA to the then president of the Socialist Group, Ernest Glinne.

Throughout the 1980s Adamson worked alone, first as a lobbyist for a clutch of UK consultancies and then directly for blue-chip clients.

These days there are almost 10,000 lobbyists in the would-be capital of Europe, but in the early 1980’s Adamson was almost alone. “The good thing was that the competition was almost totally non-existent,” he says. “The bad thing was you had to create a need for yourself.”

As the EU’s power grew, Adamson had no problems filling that niche. In 1989 he bought an old town house and started hiring. But it was only when his company moved into swish new offices next door to the European Parliament that the firm really started to mushroom. In 1997, Adamson had ten staff on his books; by the end of 2001 there will be 60.

This vertiginous growth is partly a result of shrewd business deals. In 1998, Adamson sold his company to consultancy giant BSMG for “several million” and earlier this year the world’s largest PR company – Weber Shandwick – in turn swallowed up BSMG/Adamson to create Brussels’ biggest lobbying firm.

Adamson has vowed to take a back seat in the new company to allow him to spend more time publishing, politicking, keeping fit and being a family man.

Some wonder whether he will be able to let go of the reins of power after two decades of near personal control, while others worry that the ‘family firm’ will lose its ethical soul now it is but one cog in a multinational wheel.

Until now, for example, Adamson has refused to accept tobacco firms as clients. But with Weber Shandwick calling the shots this commitment has been called into question.

It would be tempting to put Adamson’s success down to corporate mergers. However, that would ignore the two decades of hard slog he has put into building up his business. It is no coincidence that his office overlooks the European Parliament. Says MEP Nick Clegg: “He took the Parliament seriously before anyone else did and people here loved that.”

Adamson certainly has the type of ‘Golden Rolodex’ one wag described Al Gore as having, but unlike the former Vice-President he has charm and charisma in spades. He likes dancing, writing skits and singing and throws probably the best annual bash in town.

For a successful businessman approaching 50 he also looks depressingly fresh-faced and stress-free. So if they do get around to making a Brussels version of The Godfather, don’t expect hard-men Joe Pesci or Tim Roth to play Paul Adamson – my money’s on Alan Alda.

=======

"It's like a game... of whack a behemoth," says Democratic Senator Amy Klobuchar on her fight in Congress to reign in big tech.

"Every corner I go around in this Capitol there's some new lobbyist," she says. "...At some point we have to get this done." Congress is trying to rein in Big Tech. But this lawmaker could stand in their way.

Tech lobbyists say Washington Rep. Suzan DelBene is the lawmaker they’re turning to as the largest tech companies face threats in Washington.

It’s hard to find lawmakers willing to publicly side with the big tech companies these days. But Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple and Microsoft have a powerful champion left on Capitol Hill: Democratic Rep. Suzan DelBene of Washington state.

And as Congress gets increasingly close to a vote on an anti-monopoly bill that would rein in the tech titans’ power, the lawmaker from Amazon and Microsoft’s home state could be a major reason that it fails.

DelBene has used her perch as chair of the business-friendly New Democrats caucus to push back on some of the most aggressive efforts to regulate or restrain Silicon Valley, which she claims would hurt the economy and hamstring the tech industry.

Now Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi are under pressure to hold a vote this summer on the American Innovation and Choice Online Act, S. 2992 (117) — a bill that would prevent tech companies from using their gatekeeper power to disadvantage competitors.

And the tech industry has DelBene in their corner, leading opposition in the House.

“We love Representative DelBene,” said Rob Atkinson, founder and president of the tech-funded think tank Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. (DelBene is an “honorary co-chair” of the think tank.) Atkinson said DelBene is a key proponent of policies that favor “innovation.”

Behind her back, some of DelBene’s congressional colleagues, both moderates and progressives, gripe that she is an apologist for large tech companies that are some of her most important donors.

But DelBene — who has also condemned antitrust efforts in Europe against tech companies and spent years pushing privacy legislation backed by industry — argues she is an even-handed lawmaker with a special understanding of the tech industry from her 12 years as an executive at Microsoft, and startups before that.

“This is something I have a lot of understanding on and want to make sure we have strong, durable policy for the long term,” Delbene said in an interview. “I think that’s important on privacy and that is important on antitrust.”

Asked about her critics, DelBene said: “It’s unfortunate when, instead of engaging, people question folks’ integrity.”

DelBene denies that she follows the lead of the biggest tech companies. She was one of the first lawmakers to introduce legislation that would protect online privacy and supports an increase in funding for the country’s major antitrust enforcers, the Federal Trade Commission and the Justice Department antitrust division.

And, DelBene’s office pointed out, she’s recently pushed for privacy-related sections that industry does not support, referring to provisions of a bill currently in the House Energy and Commerce committee that would require companies that are “large data holders” to conduct compliance audits and provide the results to the FTC.

DelBene, who has a serious demeanor and the professionalism of a former corporate executive, is known on Capitol Hill as friendly but persistent. She has a habit of lecturing her colleagues on how certain parts of the tech industry, such as e-commerce and online advertising, operate.

Nick Martin, DelBene’s spokesperson, said the congresswoman isn’t opposed to antitrust reform in general, but she has specific concerns about the multiple antitrust bills under consideration right now, which she has agitated against since they passed out of the House Judiciary Committee last year.

That includes the American Innovation and Choice Online Act, which Schumer has pledged to put on the floor as soon as this summer. If it moves through the upper chamber, the companion bill in the House is likely to quickly follow.

In interviews, half a dozen lobbyists for big tech companies said they see DelBene, with her key position of power in the House, as the tech industry’s most effective champion on Capitol Hill.

“She is playing a key leadership role in the House, elevating the unintended consequences of antitrust reform to small businesses, to our national security, to privacy and the cyber protections that the targeted companies provide both at home and abroad to consumers,” said Carl Holshouser, senior vice president for operations and strategic initiatives at TechNet, a trade group that represents large tech companies including Google, Facebook’s parent company Meta, Amazon and others.

DelBene has particularly rubbed several of her fellow New Democrats the wrong way with her advocacy. When she spearheaded a letter last year calling to delay the committee markup of the House Judiciary antitrust bills, a number of the New Democrats’ 98 members expressed frustration and claimed it did not speak for the whole caucus.

Since then, DelBene has made personal appeals to several lawmakers who are considering supporting the antitrust legislation, at various points approaching lawmakers on the House floor during votes to try to convince them not to support the bills, according to two aides familiar with the interactions. The aides were granted anonymity because they were not authorized to speak on the record.

DelBene said she and others have “continued to express concerns” about the bills. Many members of the California delegation have raised their own qualms with the legislation targeting their home state companies. And beyond them, DelBene noted that a group of Senate Democrats argued in a recent letter that the legislation could affect the platforms’ ability to take down hate speech and misinformation. The co-sponsors of the bills, including House Judiciary antitrust subcommittee chair David Cicilline (D-R.I.) and Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), have said those allegations are untrue.

During a private meeting earlier this year with Cicilline, DelBene, who has many Amazon employees in her district, was one of only two members of the New Democrats to raise concerns about the bills’ “narrow focus on a few select companies,” said a House aide familiar with the call, who was granted anonymity to speak about a private conversation. Only 12 members of the centrist New Democrats attended the call, along with an assortment of staffers.

“DelBene has not been shy in her resistance to regulating the tech platforms and creating more competition in the ways that the House antitrust subcommittee is intending to do,” said Sarah Miller, executive director of the anti-monopoly think tank American Economic Liberties Project.

Staffers with the House Judiciary Committee who are advocating for the legislation have hit back by encouraging members of the New Democrats to sign onto the bills as co-sponsors. Ten members of the caucus have signed onto one of the antitrust bills in recent months, according to the most recent list of cosponsors.

“The top line is, DelBene has said she has spoken for a coalition of moderate Democrats with one voice, as anti-tech regulation,” said one of the congressional aides, who works for a member of the New Democrats. “But she is not speaking for all New Dems. That’s obvious by the co-sponsorship of the bills.”

DelBene’s rejection of the antitrust legislation does differ from that of Microsoft, her former employer which has headquarters in her district. (She was a corporate vice president for Microsoft’s mobile communications business for several years. Before that, she worked on marketing and product development — including on Windows and Internet Explorer.)

Microsoft, which faced years of antitrust-related lawsuits, has lobbied in favor of the antitrust bills, claiming that the tech industry should be regulated.

Adam Kovacevich, a former Google lobbyist who now heads the Chamber of Progress, a trade association funded by companies including Google and Meta, said DelBene is a “moderate pragmatist” focused on representing the views of her pro-tech constituents.

Many of DelBene’s detractors point to her financial backers as proof that she is excessively aligned with the tech industry. DelBene’s individual donations list reads as a who’s who of the tech industry’s Washington influence machine. She has received $144,534 from tech executives and lawyers, including Amazon’s top lobbyist Brian Huseman, Google’s chief legal officer Kent Walker, and Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella. (DelBene is one of a handful of lawmakers that Nadella has donated to, including California Democratic Rep. Ro Khanna and Washington Democratic Rep. Adam Smith).

She has also received around $129,500 from Google, Amazon, Facebook, and tech trade groups Technet and the Consumer Technology Association since she came to Congress — a sum much larger than lawmakers overseeing tech-heavy districts like California Democrats Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) and Anna Eshoo (D-Calif.). Still, that’s much less than Rep. Zoe Lofgren, who has received more than $270,000 from the big tech companies’ PACs. Lofgren is one of the other major lawmakers speaking out against the antitrust bills in the House.

DelBene said her campaign contributions do not influence her policy decisions. “People support me because they believe in me and the job that I’m doing,” she said.

DelBene argues the tech issue Congress should be focusing on is data privacy rather than antitrust. It’s an argument that the tech industry has turned to as well. While the largest players in the tech industry can likely handle the barrage of new costs and regulations that privacy regulation would create, overhauling antitrust laws could mean fundamentally changing the companies’ business practices and seriously hurt their bottom lines.

DelBene was one of the first lawmakers to introduce privacy legislation back in 2018, just as the tech industry was beginning to push for a light-touch federal privacy law. Her legislation, which would give users control over whether companies can share or sell their private data, has drawn support from industry groups like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

Some privacy advocates say her legislation, the Information Transparency and Personal Data Control Act, doesn’t give consumers enough rights and would undercut tougher state laws. But DelBene says the legislation is a compromise that protects consumers’ rights while helping small businesses stay afloat.

“The important thing on privacy is that we have a consistent policy across the country so peoples’ rights are protected everywhere,” DelBene said. “We have five different state laws now and they’re all different. That makes it incredibly difficult for small businesses and others to be able to keep up with different policies and how to apply those different policies.”

It’s unclear whether the American Choice and Innovation Online Act will go to a vote over the next few months. But either way, DelBene has staked out a position as a lawmaker who’s willing to support the tech industry’s efforts.

“She looks at policy questions and she really tries to call them as she sees them,” said Atkinson, of ITIF. “In this case, she firmly believes that these innovations are going to be critical to our country’s future. She’s willing to stand up and say that.”

========

How one man came to rule political speech on Facebook (bigger power rather than Aura Salla, Facebook META lobbyist in EU), command one of the largest lobbies in DC, and guide Mark Zuckerberg through disaster —- and straight into it.

EVEN BY THE standards of the Trump White House, the crisis that unfolded on the morning of May 29, 2020, was a memorable one. That Friday, a handful of staffers found themselves crammed into a West Wing office around a phone, some listening in guarded disbelief. Mark Zuckerberg was on the line, asking for a word with the president.

Minneapolis was in its fourth day of mass protests, which had not relented since George Floyd was killed under the knee of police officer Derek Chauvin. Early Friday morning, around 1 am Eastern, President Donald Trump had published a 102-word philippic to his Facebook and Twitter pages. He pledged the support of the US military and appended a hellish augury: “When the looting starts, the shooting starts.”

Among Facebook’s leaders in Washington, DC, the gravity of the dilemma this posed for the company was instantly clear. For four years, Zuckerberg had walked an impossible tightrope, attempting to assuage two implacable tribes. At one pole were powerful conservatives for whom it had become an article of faith that Facebook was sabotaging the right. At the other were Democratic legislators—to say nothing of Facebook’s left-leaning employees—who believed the precise opposite, accusing the company of rewriting its rules to pave the way for Trumpism. Now it was as if Trump, gazing up at Zuckerberg’s high-wire act, had yanked down hard on the line.

While Zuckerberg slept three time zones away, the management of the crisis fell largely to Joel Kaplan, Facebook’s vice president of global public policy and the leader of the company’s DC office. By the time the CEO woke up, Kaplan’s team had prepared a strategy memo for him, offering three ways to interpret Trump’s looting-and-shooting remark. The phrase could be read as a discussion of the state’s use of force, or as a mere hypothetical prediction. Either were allowed under Facebook’s terms of service. Or it could be understood as an incitement to violence, which Facebook does not allow, even for elected leaders; under that reading, the post would have to come down. Just the previous day, however, Trump had signed an executive order that took aim at social media companies, calling out Facebook by name for participating in “selective censorship.” To some in Facebook’s DC office, Trump’s post was practically a dare: All understood that tampering with it would likely spell the end of Facebook’s delicately managed relationship with the White House.

So Kaplan and his staff pursued another solution: They were attempting to wrangle the unwrangleable president directly, to enlist him in helping Facebook's case. White House staff had already heard from Facebook at least once that morning. But it was when the billionaire CEO himself later appeared on the line, with Kaplan listening in silently, that administration officials truly sensed the company’s urgency. “I have a staff problem,” Zuckerberg said, describing the uproar the post was causing at headquarters. One person familiar with the call thought Zuckerberg sounded like he wanted Trump to “bail him out.” Around the White House, officials summarized Zuckerberg’s appeal with leery amusement: “Mark doesn’t think there’s anything wrong with” Trump’s post, they snickered, “but his staff is going to kill him.” (Meta denies Zuckerberg said anything to this effect, and says that he was always unequivocal in condemning the post.)

In the early afternoon, Zuckerberg’s cell phone rang. It was the president. As Zuckerberg would publicly tell the story, he chastised Trump for his “divisive and inflammatory” post, but the men agreed that it would stay up. A short while later, a second post appeared on Trump’s Facebook page. In somewhat lawyerly detail, he announced that his use of “looting and shooting” was “spoken as a fact, not as a statement,” nor an incitement. “I don’t want this to happen,” he wrote, a declaration that seemed to place his post squarely inside the bounds of Facebook’s terms of service.

As some Facebook employees recount, it was like Trump could have been reading from the Kaplan team’s memo. In a Facebook post, Zuckerberg would later say he found Trump’s post “deeply offensive,” while appearing to suggest that the president’s timely follow-up had bolstered Facebook’s rationale to leave it untouched. A conservative revolt against Facebook had been temporarily averted. Facebook’s liberal staff remained incensed—hundreds staged a virtual walkout to protest the decision—but most grumbled cynically and went back to work. “This was like a four-alarm fire,” a former senior Policy staffer who worked closely with Kaplan told me, and Kaplan had “put it out.”

In Silicon Valley, Joel Kaplan is regarded as one of Facebook’s most curious enigmas. Hired in 2011 after eight years in the Bush White House, his tenure has coincided with Facebook’s rise to global dominance—and its ascendance to the throne of permanent controversy. Formally, Kaplan’s role is to forecast and manage policy risk. Functionally, his authority is as sprawling as the company’s reach. The 52-year-old has not only assembled one of history’s most prolific lobbies in Washington, where he manages relations across the federal government as well as with state capitals and their increasingly avid attorneys general. He also leads a team of a thousand Policy staff worldwide, assessing, shaping, and often thwarting the boundless constellation of international laws and policies that graze Facebook’s business and its 2.9 billion users across the globe, from German privacy rules to Iowa firearm laws to Indian political parties. For a company whose power has no equivalent, Kaplan’s is a job without precedent. One person described Kaplan to me as “Washington dark matter”—exerting powerful gravitational forces but strangely hidden. Hany Farid, a professor of computer science at UC Berkeley and a recent adviser to the Biden White House on tech reform, told me that “Joel Kaplan is probably the most influential person at Facebook that most people have never heard of.”

But Kaplan—who declined to comment for this story—has another role that drags him out of anonymity: helping to design and arbitrate much of Facebook’s policy on political speech. Since the 2016 election, the platform’s approaches to its most controversial challenges—including fake news, algorithmic ranking, and hate speech—have been furnished to varying degrees from the mind of Kaplan. He has played a pivotal role in exempting politicians from Facebook’s community standards, protecting shock-jock sites like Breitbart from punishment, and throttling algorithmic changes that might have made Facebook less politically polarized. Employees believe they’ve seen proof of Kaplan’s right-wing favoritism—the subject of at least one sworn affidavit in a whistleblower action, and an obstacle for employees who describe part of their duties at Facebook as making their product ideas “Joel-proof.” Others describe a fair-minded manager and compassionate mentor, to whom many Facebook staffers, including staunch liberals, remain profoundly loyal.

Kaplan’s many defenders argue that he is merely an envoy of a free-speech ideal that reflects a vast constituency of Facebook users. Critics see a malign influence responsible for steering the company rightward. Kara Swisher, the prominent tech commentator, has labeled him a “menace.” Last year, Jim Steyer, CEO of Common Sense Media and an unrelenting critic of Facebook, said publicly that Kaplan would “go down in history books as one of the people who have caused great damage to our democracy.”

This burgeoning profile has begun to dog Kaplan in Washington. In 2019, after he was photographed striding through the Rayburn Building on Capitol Hill, where many congressmembers have their offices, Senator Elizabeth Warren tweeted that “Kaplan is flexing his DC rolodex” to help Facebook evade regulation. Last year, the civil rights group Color of Change launched a new campaign: #FireJoelKaplan. More recently, Kaplan has been targeted by the DC attorney general, whose lawyers have demanded to see his emails. In a town where Big Tech’s fortunes have long been burnished by prominent fixers—who exist primarily to repel unwanted controversy—arguably no fixer has attracted more controversy than Kaplan.

Today the limits of Facebook’s influence in Washington are being tested. Congressional Democrats are racing to pass legislation that would limit Facebook’s power, and that President Joe Biden could sign before this fall’s midterm elections. Meanwhile, White House appointees in the Federal Trade Commission, Federal Communications Commission, and Department of Justice are leading headstrong efforts to circumscribe Big Tech, including a federal lawsuit brought by FTC chair Lina Khan to break up Facebook. “I think 2022 is going to be the pivotal year,” says Steyer, who has worked with the White House and Congress on their approach to Facebook. “For the first time, Facebook is genuinely going to be held accountable.”

Optimism like Steyer’s stems in part from two events in 2021—the January 6 attack on the Capitol, which was heavily coordinated on Facebook, and the testimony of product manager turned whistleblower Frances Haugen—that have brewed the conditions for cooperation across the aisle. Bipartisanship is a force often frivolously invoked inside the Beltway. But Brendan Carr, the highest-ranking Republican on the FCC and a vocal Trump supporter, largely agrees with Steyer. Facebook, he says, “has lost all their friends in Washington.”

Facebook may be politically friendless, but Joel Kaplan is not. Most think the influence network he has assembled will be a formidable obstacle for leaders of the techlash. Having spent $20 million last year, Facebook is now running the second-largest lobbying effort by a public company in the US, only shy of Amazon. David Cicilline, the Democratic representative who has led the push for antitrust legislation, describes the salvo as “an armada of lobbyists descending on Capitol Hill.”

“They have a lot of money, a lot of power, a lot of influence,” says Mike Davis, a longtime Republican official on Capitol Hill who founded the Internet Accountability Project. “If these bipartisan bills pass, or even two or three pass, they’re going to get rocked. And it’s going to cost them a lot of money.” In certain ways, a battle of such proportions is the natural culmination of Kaplan’s career, one that has been devoted to defending the most powerful institutions in America. As Davis bluntly puts it, “This will be the biggest fight of Kaplan’s professional life.”

Long before he ever heard Mark Zuckerberg’s name, Joel Kaplan was shaping the world that Facebook would someday dominate.

The youngest of three children, Kaplan was raised in middle-class Weston, Massachusetts. Both his father, Mark, an attorney for municipal unions, and his mother, a college administrator, were liberal Democrats. Kaplan went to Harvard, where, on the first night of orientation, he met a twiggy and curly-haired freshman from Miami named Sheryl Sandberg. The two would date briefly that year. He was also an active student Democrat and successfully campaigned to be a ward delegate at the statewide Democratic convention. In student government, he championed randomized student housing, telling The Crimson, “Segregation, voluntary or involuntary, accentuates differences and breeds intolerance.”

In his senior year, however, signs of a shift began to manifest. That February, the US invaded Kuwait, and Kaplan watched the campus roar to life with anti-war activists, who marched with gas masks and chanted their parents’ slogans from Vietnam. The experience, says Kristen Silverberg, a student at the time who later became friends with Kaplan, presented “an extreme version of Democratic politics on a largely liberal campus” that left many students cold. By the end of senior year, Kaplan had omitted the Democrats from his yearbook activities. Shortly after graduating, he joined the Marines.

In 1992, Kaplan reported to Quantico to begin training as an officer. Having missed the war, his tour in garrison mostly involved leading training exercises at Camp Pendleton. After more than three years in uniform, Kaplan returned to Harvard as a law student—and by the end would be telling classmates that he was a conservative. He finished his first year near the top of his class and lost the Law Review’s prestigious presidency by a single vote. Agreeable to compromise and disinclined to culture war, Kaplan sometimes called himself a “Colin Powell Republican.” (He wrote in the general’s name for president in 1996.) But within the GOP, Powell’s brand was fading. In the summer of 1998, after heading to Washington for a judicial clerkship, Kaplan befriended a star lawyer named Brett Kavanaugh, who had just rejoined Ken Starr’s investigation of President Bill Clinton, and watched his friend rocket through the ranks of the conservative elite. (For DC’s hotshot conservatives, Kaplan later jokingly told an audience, Kavanaugh was an exemplar: “Even the most socially challenged groups need role models, and we had Brett.”)

By 2000, Kaplan was clerking for Antonin Scalia, the Supreme Court’s most prominent conservative, and in July he joined George W. Bush’s presidential campaign as a policy aide to Dick Cheney. On November 8, the night of the election, as the networks scrambled to call the Florida results, the Bush campaign scrambled to find lawyers. By 6 am, Kaplan was on a flight to Miami, the sun rising on what would later be described as one of the most contested and combustible events in American politics. At 31 years old, Kaplan had never seen combat, but he was about to go to war.

As Bush’s lead in Florida shrank to 300 votes, the Gore campaign requested a hand recount in four counties, including deeply Democratic Miami-Dade. On November 21 the Florida Supreme Court ordered the recounts to proceed, and to declare a winner in five days. For the first time, it appeared to many in both campaigns that Gore—fairly or unfairly—was about to win Florida.

Early the next morning, Kaplan joined Bush lawyers who arrived at the Clark Center, a drab government building in downtown Miami. In a conference room on the 18th floor, attorneys from the two campaigns assembled before Miami-Dade’s local election authority, the Board of Canvassers: two local judges, plus Miami’s supervisor of elections, a wizened official named David Leahy.

The purpose of the hearing was to start the recount, but, as Leahy explained, it was impossible to hand-count all of Miami-Dade’s 650,000 ballots within five days. Since tallying all the votes was Gore’s best scenario, and counting none was Bush’s, Leahy suggested a compromise: Tally the 10,750 mystery ballots that machines—unable to read the “hanging chads”—had failed to count. This, Leahy estimated, would take only 36 hours. Taking half a loaf, the Gore lawyers agreed. Kaplan and the Bush lawyers, meanwhile, bitterly opposed the idea: Either all the votes should be counted, they argued, or none should.

Watching quietly from the side of the hearing room was Mayco Villafaña, the media spokesperson for Miami-Dade. A reedy, quiet, patriotic man whose father had languished in one of Fidel Castro’s prisons, Villafaña believed that work in government was a noble calling. “It’s about integrity,” Villafaña says. “You do your duty. And you do not inject your own biases or opinion.” When the political elites and lawyers converged on the Clark Center to adjudicate the peaceful transfer of power, he assumed they would share this unspoken view. “I was naive,” Villafaña says.

The Gore campaign largely approached the recount as a legal proceeding. The Bush campaign had summoned political operative Roger Stone to Miami to help organize rowdy protests against the recount. Outside the Clark Center, Stone was in a rented RV using walkie-talkies, he would later say, to direct a defiant circus of costumed Bush protesters in the open-air plaza surrounding the Clark Center. About a hundred Bush supporters were also packed into an 18th-floor hearing room at the moment when the canvassers unanimously voted to start the hand count immediately. Without much thought, Leahy casually proposed they do the recount upstairs, in the county’s 19th-floor election office. Away from throngs of onlookers, each campaign would have two observers in the room at a time, to watch the count up close; the Bush campaign chose Kaplan to be one of its observers.

By moving the count out of public view, Leahy had made an impetuous but catastrophic mistake. “We were not ready for what happened,” Villafaña says. “All hell broke loose.”

A crowd of Bush supporters made for the 19th floor. There, they poured into a constricted vestibule with a broad glass window peering into the election office and a secure access door for authorized personnel. With startling speed—“a flash fire,” Villafaña says—the mass swelled to somewhere between 50 and 80 people in a room meant for a dozen at most, and erupted in chants: “VOTER FRAUD! VOTER FRAUD!” and “LET US IN! LET US IN!” The crowd, almost entirely men, started banging their fists on the windows and kicking the doors—audible to election workers inside. On the door’s opposite side were Villafaña, two sheriff’s deputies, and Ed Hollander, Miami-Dade’s chief of security. When the door was opened, the crowd grabbed it, and the four men struggled to get it closed, pulling with all their weight to keep it shut. It was bulletproof, Hollander knew, and locked from the inside. But a stream of lawyers and officials needed to get in and out.

At one point, as the crowd wedged the door open, a ruddy-faced man started kicking Villafaña. “Don’t hit me! Don’t hit me!” the man shouted loudly, in earshot of a CNN camera, while he stomped Villafaña in the shins and thigh. Others got the idea and began shoving Villafaña. “Don’t hit me!” they shouted, and started getting in the faces of observers, who now had to push their way to the door in a hurricane of noise: “Whore!” protesters screamed at one observer. “LET US IN!”

Looking out on the crowd, it occurred to Hollander that the outcome of a presidential election hinged on a room full of ballots that were being counted less than 50 feet from a battle zone. As Hollander recalls, “If people were to break into that office, or storm it, then thousands of votes could have been at risk.” Inside there were also county officials, campaign operatives, and judges. “If that mob got in, I would fear for their safety.”

Downstairs, a Republican representative urged on a crowd of Bush supporters by declaring that they were witnessing “the stealing of a presidential election.” Upstairs in the vestibule, Hollander thought the scene was no longer just a rowdy protest but had taken on an air of insurgency. At least two election officials had been kicked and punched. So on his radio, Hollander called in a “315”—code for emergency officer reinforcements. He told the deputies to guard the ballots no matter what, and to keep the door shut until backup arrived. For the time being, the protesters had succeeded. The count was frozen.

Around 10:30 am, inside the tabulation room in the 19th-floor election office, Leahy huddled with Kaplan, alongside Bush lawyer Neal Connolly and Gore lawyer Jack Young, deliberating whether the board should adjourn downstairs. Villafaña had installed audio equipment and a camera inside the elections office, and a few reporters hovered nearby. What happened next was captured by a young Jake Tapper, who later recounted the scene in his book Down and Dirty.

Villafaña, Tapper wrote, asked both the Gore and Bush lawyers if they would each tell the protesters to return peacefully to the 18th floor. Young immediately agreed. Then Leahy cut the air. “Until the demonstration stops, nobody can do anything.”

Kaplan spoke first. “I suspect that if the announcement was made by—” Villafaña cut him off. “The announcement needs to be made by someone in the party.” Stalling, Connolly interjected: “Would the board be able to issue a couple of sentences?”

“They will listen, I think, to someone from the party,” Villafaña said.

“I don’t know if they would listen to us, or the other side,” Connolly replied. Young cut in: “I don’t believe it is both parties.”

Kaplan said nothing. That’s when Connolly made the Bush position clear. “I would simply request that the board affirmatively state that it intends to come downstairs as soon as possible.” In other words: The Bush campaign would not ask protesters to clear out until the board agreed to move. The board would reconvene downstairs—just as soon as backup officers arrived and could secure both floors.

Three hours later, the Board of Canvassers filed back into the conference room. Without warning, the board announced that it found itself in “a radically different situation.” The melee had slowed counting to a trickle, and Leahy couldn’t guarantee that the process could be concluded. Over the objections of stunned Gore lawyers, and to cheers from the Bush crowd, the board reversed itself, halting the recount.

The Brooks Brothers Riot, as the event would be called—on account of the shirts and blazers worn by many in the angry crowd—briefly became the subject of high-minded Washington palaver. Representative Jerry Nadler condemned the use of “mob violence and intimidation,” while another congressperson asked the FBI to investigate the rioters. Later, video footage would identify several who swarmed the elections office as professional Republican operatives: congressional aides, staffers from the National Republican Congressional Committee, two congressmen, and at least two Bush campaign staffers. It would take months before the public learned how the flash fire had started. A Republican representative, John Sweeney, had incited the crowd to storm the election office, instructing two aides over the phone: “Shut it down!” Roger Stone appeared to have contributed too: “I said ‘Flood the hall,’” he recounted, years later. “And don’t let them shut that door.”

But by then, the ordeal was lost in the fog of the recount saga. In 2001, David Boies, Gore’s lawyer, described the event as the recount’s turning point. The campaign had projected the undervotes to put Gore narrowly ahead. “I think that would have changed things,” said Boies.

The Bush campaign, meanwhile, framed the events as a populist act of patriotic necessity. A campaign press release announced that Leahy’s Canvassing Board had taken “10,000 ballots to the 19th floor to count them in secret” and described the crowd’s actions as “inevitable and well-justified.” At a campaign celebration the day after the riot, protesters mingled with the Bush team. Later, when Bush and Cheney called in by speakerphone, Cheney singled out Kaplan for praise, joking that his shy policy aide made for an unlikely rioter.

When Villafaña later discovered that those who kicked and shoved him weren’t Miami locals but Washington professionals, he was stunned. “I do believe it was violence. And I do believe it did have an impact on the decision of the Canvassing Board.” He quit local government a few months later.

Like several others at the Clark Center, Kaplan went into the White House in 2001. As a policy aide, he was a star. He made his colleagues laugh with disarming self-deprecation and earned a prized Bush nickname: “Blade.” Kaplan was largely untroubled by Miami-Dade, until 2003, when the White House nominated him to a senior role in the Office of Management and Budget. At his confirmation hearing he was confronted by Frank Lautenberg, the ancient senator from New Jersey and a World War II veteran. Lautenberg asked Kaplan to name his relevant job experience, and Kaplan began by referencing his “experience as an officer in the Marine Corps.”

“Platoon leader,” Lautenberg said coolly.

“Platoon leader and then an executive officer.”

Why, then, Lautenberg asked, had Kaplan done nothing when Leahy pleaded with him to calm the rioters? “Why you, with all of the training that you have had in the law, and the skills, the academic background that you bring?” he asked. “You knew what was happening.” Why hadn’t the platoon leader come to the lobby and simply announced, “We have our observers. Everything is aboveboard”?

Kaplan replied that his role was that of an election observer, and that he “was not in charge of the people who were congregated outside.” Lautenberg didn’t press the subject much further, and a few weeks later Kaplan was confirmed as deputy director. But the exchange stuck out in the mind of Villafaña, who, although he barely knew Joel Kaplan, suspected he knew the answer to Lautenberg’s question: “To win at all costs.”

Kaplan remained in the Bush White House for all eight years. He rose to deputy chief of staff, managing a wide terrain of domestic policy issues, including federal surveillance law and immigration reform. He also proved adept at the Washington gamesmanship required to protect his boss.

In late 2007 the Environmental Protection Agency was on the brink of a historic feat: declaring that greenhouse gases posed a direct threat to the public through climate change. On the afternoon of December 5, an EPA official named Jason Burnett emailed the agency’s official but unpublished Endangerment Finding to the Office of Management and Budget, thus triggering a federal review process that would in all likelihood lead to the first-ever regulations of CO2 emissions from vehicles and, eventually, power stations. A half-hour later, Steven Johnson, Bush’s EPA administrator, walked into Burnett’s office. As Burnett recalls, Johnson had just gotten off the phone: Joel Kaplan was asking them not to send the report to the OMB. When Burnett said he’d already sent it, Johnson left, then came back five minutes later. “Joel is asking whether you can send a follow-on email, saying you sent it in error.”

“And I said, ‘Well, no—because I didn’t,’” Burnett recalls, laughing. “This is the key environmental issue of our time, the evidence is clear. No, I didn’t send it ‘by mistake.’” Johnson went back to the phone and again returned a few minutes later. “OK, Joel is going to tell Susan Dudley”—the OMB official who had received the EPA document—“not to open your email.” Burnett was speechless, and also somewhat impressed at Kaplan’s logic. Under a certain theory, if the email remained unopened, the OMB wasn’t in receipt of its contents. “And if you’re not in receipt of its contents, then you don’t have to take action that would flow from having received this Endangerment Finding—literally, that the public is in danger from climate change.”

After the email sat unopened for weeks, Johnson drafted a letter directly to Bush. It read, “I have concluded that it is in the Administration’s best interest to move forward” with the EPA’s three-phase plan to regulate greenhouse gases. In January, Johnson sent the letter to the White House by courier. At the top, on EPA stationery, was a hand-scrawled note to Kaplan: “Joel, I really need your help in bringing these issues to closure. Thank you, Steve.” According to Burnett, Kaplan called a few days later and told Johnson to have someone from the EPA come over and take the letter back. Six months later, the EPA issued a new version of its findings; this time it did not make any formal recommendation.

When Bush’s term ended, Kaplan went to work for a Texas energy company. But he had kept in touch with Sheryl Sandberg, who was looking to build out Facebook’s small team in Washington. Kaplan joined in 2011, overseeing domestic policy. He understood little about how the internet worked and had to be taught by snickering staff. Yet the company’s main concern in DC at the time wasn’t fending off laws but building an image. In Washington, Facebook’s trajectory was reflected in its ever changing lease: from a cramped walk-up in DuPont Circle to swankier F Street digs in Penn Quarter to the Warner building on Pennsylvania Avenue—each move inching closer to the White House.

In 2014, Kaplan was promoted to Facebook’s top job in Washington. Staffers were intrigued by their new boss. “At heart, he’s a policy wonk,” one Democratic consultant says, adding that Kaplan “likes to get his fingers dirty.” Another stresses Kaplan’s “platinum relationships” on both sides of the political aisle. At Facebook, Kaplan’s wry humor made him well liked. “He will charm the shit out of you,” says a former senior executive. “That is one of his great superpowers.” At least among male staffers, he occasionally referenced JJDIDTIEBUCKLE, the 14 values of the Marine Corps. One woman remembers a short-lived nickname, taken up by besotted staff: Joel Kaplan, they said, was a “Leader of Men.”

At Kaplan’s direction, Facebook began to hire and promote an array of professional Democrats and Republicans, in roughly equal measure. One was Crystal Patterson, a polished Democratic operative who’d worked for Hillary Clinton. Another was Katie Harbath, a well-traveled Republican, whom Kaplan put in charge of Facebook’s global elections team. Both women describe Kaplan as brilliant and an even-handed manager who openly welcomed criticism. He was also unsparing when evaluating his staffers’ ideas. “He is really good at finding the loose threads and pulling on them,” Patterson says. Harbath describes Kaplan’s “Socratic method to managing,” stress-testing proposals with a barrage of questions. The exercise had two purposes: “Number one,” Harbath says, was to ensure the idea was not putting Facebook’s “thumb on the scale” of a thorny or intractable issue. “And number two, to make sure that it didn’t look like we were doing that when we weren’t.”

In December 2015, Donald Trump, then a candidate in the Republican primary, proposed banning all Muslims from entering the United States. When his remarks were posted to his Facebook page, even Republican staffers acknowledged that the video violated the company’s hate speech policy. But in a videoconference meeting where executives considered taking the post down, Kaplan argued for leaving it up. He warned that deleting the video would invite outrage from conservative America. The room included prominent Democrats, such as Sandberg and communications vice president Elliot Schrage. But after discussion, the team converged on Kaplan’s position and decided to leave the post intact. The conversation, as later reported by The New York Times and WIRED, essentially invented Facebook’s political “newsworthiness exemption”: a rule that would allow politicians to violate Facebook’s community standards without punishment. In making his argument, according to the Times, Kaplan had warned that taking down Trump’s video would be the political equivalent of poking a bear. (Meta spokesperson Dani Lever denies that Kaplan said this.)

Staffers describe the decision as a pivotal moment in the company’s history—when Facebook decided it would fundamentally reflect the political world rather than referee it. Many liberals at Facebook, Patterson included, came to view the ruling as disastrous. “This was an easy call. He wasn’t president yet—in fact, nobody thought he was going to win,” she says. “I think that helped him win legitimacy.” Conservatives defended the choice: Harbath notes that the video was already widely reported and that removing content by a presidential candidate would be unprecedented. Hany Farid predicts that Kaplan’s role in creating the newsworthiness exemption will be viewed as an early moment when elites sat down to craft the core values of the social web and got things precisely backward. People in positions of power should be held to higher, not lower, standards, Farid argues, and not despite their public reach but because of it, when “they have the power to do so much more harm.”

Warning Zuckerberg of potential political blowback was elemental to Kaplan’s job. But Kaplan’s “Don’t poke the bear” mindset soon evolved into an ethos that, as Patterson puts it, “seemed to inform all of our engagements with the Trump White House and the Trump campaign.”

Soon enough, the bear was poked anyway. In May 2016, Gizmodo published allegations that Facebook’s Trending Topics widget was biased against conservative publishers and news. The story rocked the conservative establishment. One Republican senator threatened to haul Facebook executives before the Senate. A former senior Policy staffer who watched the scandal detonate in Facebook’s Menlo Park headquarters says, “It scared the shit out of the Republicans in the office.”

Hours after the allegations were published, Kaplan dialed an old friend working on the Trump campaign. They conceived a Menlo Park summit where company leadership would fete conservative heavyweights. In all, 17 guests were flown in, including Glenn Beck, Tucker Carlson, and former Bush press secretary Dana Perino. In a glass conference room in Building 20, Kaplan opened a carefully choreographed presentation with an update on the company’s internal investigation. Then Zuckerberg described to the VIPs how the platform would weed out anti-conservative bias. Afterward, guests were given a special tour, including a demo of a prototype VR headset. When reviews of the summit came back favorable, Kaplan appeared to have pulled a rabbit out of his hat.

There was just one problem: The Gizmodo allegations weren’t true. Data suggested that, if anything, conservative news was over-indexed in Trending Topics. But it hardly mattered: Facebook had encountered a political scandal that couldn’t be fought with facts. Kaplan had contained the damage, a contribution not lost on Zuckerberg. “It was probably one of the first really big moments of Joel being able to showcase that to Mark,” Harbath says, and “being able to be a trusted adviser to navigate issues on the right.”

The morning after Donald Trump won the presidential election, Kaplan led a conference call to reassure his shell-shocked colleagues. Within days, people across the company would observe Kaplan wielding new powers, and they watched Facebook transform from a campus that had once given Barack Obama a standing ovation to a company terrified of appearing too liberal. Throughout 2016, Zuckerberg had made political statements at odds with Trump’s agenda, positions that would demand rehabilitation with a party now in unified control of Washington. “There was nobody else around Mark, in his inner circle, that came from that world and could help do that,” Harbath says. “Zuck really did not want the company to be political,” says one senior product official. “That’s when Joel first started to realize: There’s no political will here in a very political situation. And obviously, if you’re smart, you love nothing more than a game where you’re the only one playing.” After Trump’s election, “Joel became the loudest voice in the room.”

FOR 10 YEARS, company culture at Facebook had been dominated by product and growth engineers. During the Trump transition, a new normal emerged. Sensitive discussions about product development were increasingly expected to include senior Policy members, including sometimes Kaplan himself. Beginning in late November, a News Feed team began meeting weekly to discuss a new innovation, fact-checking. Given the daily fire hose of news stories, fact-checkers could realistically review only 20 to 50 stories each day—a list that suddenly took on political implications. On videoconferences, a person in the meetings recalls, “Joel would raise his hand and go, ‘Wait a minute. I’d like to know what that list looks like too.’” Previously, the person says, the idea that a policy person would tell a product person how to make a decision would have been “ludicrous.”

In another meeting, that December, Facebook staff deliberated over how to handle the dozens of fake news pages generated from overseas, which Facebook was feverishly documenting in the election’s aftermath. When a person proposed deleting the pages immediately, Kaplan objected, arguing that the sudden deletions would “disproportionately affect conservatives,” according to remarks first reported in The Washington Post. Warning of Republican backlash, Kaplan cautioned: “They don’t believe it to be fake news.” He suggested deleting the pages, but only after Facebook had formulated a defensible rule it could explain to the public.

The new rule, unveiled in the fall of 2017, outlawed what became known as CIB: “coordinated inauthentic behavior.” As Zuckerberg later explained, “the real issue” wasn’t the content generated by Russian accounts, but that it “was posted by fake accounts.” There wasn’t anything wrong, per se, with American users who declared #WarAgainstDemocrats or compared Hillary Clinton to Satan—as long as they were who they said they were. Kaplan was part of discussions about designing the new standard, staffers say, a joint effort by the Content Policy and Security teams.

That same fall, however, an opposite worldview was taking shape in a newly formed team called Civic Integrity. Almost immediately, staffers in the group zeroed in on the CIB policy and what they believed was its Promethean flaw: The Russian tactics of 2016 could be re-created in electoral politics all over the world—not by foreign actors but by domestic ones.

Several Civic Integrity staffers christened their concern with a half-ironic moniker: “coordinated authentic behavior.” The posts of Hungary’s authoritarian leadership, for instance, were perfectly authentic and newsworthy—and so would ordinarily not be caught in the CIB dragnet. Throughout 2017 and 2018, on trips to India, the Philippines, Ukraine, and Brazil, staffers watched as Russian-style tactics were mimicked by domestic leaders spreading jingoistic lies. Some Civic Integrity staffers even believed the dilemma posed a greater future threat to democracies than CIB. During one 2017 meeting, one staffer flagged the dilemma: “What do you do when political parties use these tools in the same way—to engage in disinformation, disparaging democracy, and voter suppression—but on their own people?”

For the next three years, Kaplan’s Policy dominion would frequently clash with the company’s various Integrity teams. Perhaps the earliest significant battle arrived with a project called Common Ground. A collaborative effort that included News Feed Integrity, Civic Integrity, and other teams, Common Ground’s goals, according to early documents reviewed by WIRED, were to reduce polarization and lower the partisan temperature on Facebook. Having been encouraged by Chris Cox, Facebook’s chief product officer, the group laid out an ambitious road map to “reduce polarization” with a cocktail of “aggressive” interventions. In place of “biased news consumption,” Common Ground would “rebalance media diets”; instead of self-segregation, “exposure to cross-cutting viewpoints”; in place of “incivility,” incentives for “good conversations.”

Facebook staff were often encouraged to think up a “Facebook solution”—ideas that were scalable and workable anywhere. Common Ground, employees say, was conceived as just such a response to the 2016 election, aimed not at Russian interference but at the social fissures that had invited it. Over the next few months, it would recommend suggesting politically diverse groups to users and boosting news outlets with high bipartisan readership, such as the BBC and The Wall Street Journal. Another idea was to reduce the viral reach of hyperactive (and hyperpartisan) users, and dial up the reach of those in the political middle. Signaling their ambitions, the team hung posters that read “Reduce Hate” and “Reduce Polarization” around the Menlo Park office. “Everyone was real excited about this work,” says a former Civic Integrity staffer. “And then, yeah—it just died.”

The project had run afoul of Kaplan and the Policy team. Routinely, recalls one senior product official who sat in on Common Ground meetings, “we would have a product argument, and Joel would make it into a political one.” From the Washington office, Kaplan subjected Common Ground product managers to his Socratic approach. The review sessions were dubbed Eat Your Veggies, a title meant to convey the feeding of hard truths to idealistic liberals in Menlo Park. Chief among Kaplan’s concerns, several say, was that the changes would have an outsize effect on political conservatives.

In an important sense, Kaplan wasn’t wrong. By then, both outside researchers and Civic Integrity staff had found that political mischief on Facebook was lopsided. A small number of extreme partisan super users were disproportionately responsible for trouble on the platform, and right-leaning accounts generated and consumed a larger share of this content than others. The upshot was that seemingly nonpartisan tweaks, like Common Ground, could have partisan effects. According to The Wall Street Journal, Kaplan called the program “paternalistic.” In the end, while some Common Ground ideas survived, its most radical proposals aimed at the United States were diluted or rejected.