During the Cold War, Finland's relationship with NATO was basically non-existent. Unlike Sweden, Finland did not have a Plan B - that is clandestine preparations for wartime cooperation with the alliance. Rather, it was bound to the Soviet security system through the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance / FCMA treaty. With 1340 km of border with Russia, Finland matters, strategically and politically.

FCMA, sometimes by the global public, identified (Finland) neutral about Russia. ”Finlandisation” is something want to forget. Neutrality dropped after the Cold War. And Finland capacity to defend ourselves is based on a strong military, sophisticated arms and a network of security arrangements ranging from bilateral agreements, to the EU and NATO.

Finland, with its brand of semi-neutrality for the past 70 years and emphasis on consensus-building, tends to shift foreign policy with glacial speed. Finland’s tolerance of Putin was so embedded that some on the left claimed it strayed close to collaboration as the Finnish political elite shunned the Russian opposition.

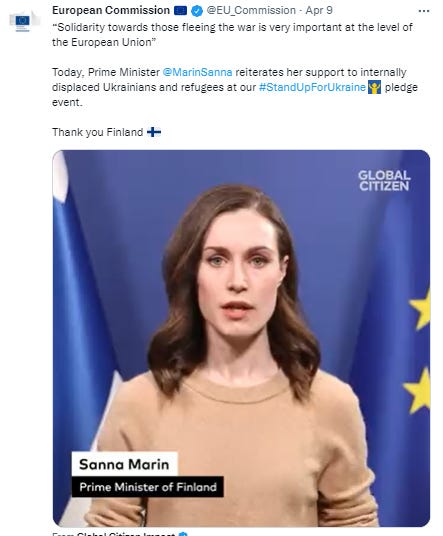

In the government’s annual survey in December, Finnish support for Nato membership stood at 24%.Four months later, Finnish politics has somersaulted. Support for Nato membership stood at 68%. Surveys now show more than half of the 200 parliamentarians back Nato membership. In the 2015 Finnish parliamentary elections, 91% of SDP candidates were opposed to Nato membership. The Finnish SDP prime minister, Sanna Marin, said everything had changed. Russia is “not the neighbour we thought it was (after invaded Ukraine)”, she said.

One of the pillars of Finnish security was based on good relations with Russia (especially because FCMA). That pillar is now gone. Russia is an unpredictable and isolated aggressor. As a consequence Finland will have to adjust its security, and it will have to do it fast, with determination.

Finnish leaders were rather lukewarm towards a robust NATO presence in Northern Europe, which was a factor increasing Soviet pressure on Finland. Interestingly, this generated friction between Finland and Norway - a detail that is often forgotten.

The end of the Cold War was a game changer for Finland's room to maneuver in international affairs. Maintaining Finland's relationship with the eastern neighbor ceased to be an overriding objective, which broadened the horizon in terms of policy objectives. Fortunately, if at least compared with all CIS’s members (ex-Sovyet), Finland military has been built to be more NATO compatible than many of its members.

Finland would have to apply for NATO membership not knowing the precise future relationship. In its security document published this week, Finland insisted: “Membership would not oblige Finland to accept nuclear weapons, permanent bases or troops in its territory. For example, in the early stages of their membership, founding members Norway and Denmark imposed unilateral restrictions on their membership and have not permitted permanent troops, bases or nuclear weapons of the alliance in their territory during peacetime. NATO’s enlargement policy, which took shape in the latter half of the 1990s, has been based on the principle that it will not place nuclear weapons, permanent troops or permanent bases in the territory of any new member country. Finland has already canvassed NATO members for security guarantees in the four months to a year that it was in the NATO ante-chamber awaiting full acceptance.

In addition to strategic rationales, Finnish politicians presented normative and identity-political arguments against NATO membership. NATO was allegedly an instrument of Washington DC hegemonic power and unlike the Eastern European NATO aspirants, and on the other side Finland did not suffer from "a security deficit".

EU membership - materialized in 1995 - was a chief priority for Finland. NATO membership again was off the table - mainly for strategic reasons. Finnish leaders saw military non-alignment as the best solution to preserve the fragile stability in the Baltic Sea region.

Finland has supplies. At least six months of all major fuels and grains sit in strategic stockpiles, while pharmaceutical companies are obliged to have 3-10 months’ worth of all imported drugs on hand. Finland has civilian defences. All buildings above a certain size have to have their own bomb shelters, and the rest of the population can use underground car parks, ice rinks, and swimming pools which stand ready to be converted into evacuation centres. And it has fighters. Almost a third of the adult population of the Nordic country is a reservist, meaning Finland can draw on one of the biggest militaries relative to its size in Europe. “We have prepared our society, and have been training for this situation ever since the second world war,” says Tytti Tuppurainen, Finland’s EU minister.

After spending eight decades living first in the shadow of the Soviet Union and now Russia and deal with FCMA, the threat of war in Europe “has not hit us as a surprise”. The improvised “total defence” strategy that has defined Ukraine’s dogged defence against Russia’s invasion, with newly-weds and shopkeepers reportedly taking up arms, has captivated people around the world. But what Finland calls its strategy of “comprehensive security” offers an example of how countries can create rigorous, society-wide systems to protect themselves ahead of time — planning not just for a potential invasion, but also for natural disasters or cyber attacks or a pandemic.

Finnish policymakers remained faithful to the central tenet of Finland small-state realism: Russia still had legitimate security interest in Finland. Taking them into account was prudent statecraft and a key to regional stability. The EU's nascent security and defense policy also started to gather steam.

Both NATO partnership and the CSDP have been crucial vehicles for the internationalization of Finnish defense policy. From mid-1990's to early 2010s, the interpretation of what is appropriate military action for a non-aligned country widened considerably.

The first decades of the post-Cold War era also gave birth to Finland's "NATO option" - i.e the instrumentalization of potential NATO membership for deterrence purposes. The option became a central part of Finland's declaratory policy in mid-2000s.

Russia's 2014 aggression in Ukraine (Crimea region) was a major watershed for Finland's defense policy. Finland has subsequently deepened its defense partnerships with Sweden and NATO allies with the aim of creating conditions for wartime cooperation. The change has been profound.

Indeed, the Russian assault on Ukraine (Feb 24th, 2022) will most likely mark a historic juncture in Finland's foreign and security policy. There are two key interconnected factors explaining why Finland is about to hand over its NATO membership application. Finland's efforts follow the balance of threat theory. The Russian assault on Ukraine intensified Finnish threat perceptions re: Russia and rendered existing arrangements insufficient in the eyes of policymakers, making a stronger counterbalance necessary.

The Russian attack has led to dramatic changes in Finland public opinion regarding NATO membership. A solid majority of Finns (60-80%) are now in favor of membership. This, as well as shifts in MPs' NATO views, has generated a massive bottom-up pressure on the leadership to act.

Although the likely turn in Finland foreign and security policy is a result of these 2 factors, the shift in public opinion has been a decisive factor. Had public views not changed, the leadership would likely have been satisfied with deeper mil cooperation outside NATO.

Finland likely NATO membership is a result of the interplay between domestic and international factors. The international environment and the shocks therein have set limits for Finland room to maneuver. The domestic landscape has deemed what is appropriate action for Finland.