When The West Restructure Intelligence and Defence for The Bigger War after Ukraine - Russia Fiasco

Feb 24th since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the fact that Ukraine is still intact and standing after 35-days of war (live update Russia - Ukraine click here), should force analysts to reconsider their assumptions. Perceptions of Russian military power and grand strategy have clearly been revised downward. Russia is still really a great power, but its primary power asset turns out to be less potent than previously believed, or overestimated. The European Union, in contrast, seems to have found a new voice and a new sense of purpose in response to Russia’s invasion. The jury is still out on the effect of the conflict on China.

A reassessment of U.S. power and strategy also seems appropriate. On the one hand, the United States failed to deter Russia from invading Ukraine, which suggests that Russian President Vladimir Putin perceived American power was on the wane. On the other hand, the potency of the post-invasion sanctions caught Russia (and other great powers) by surprise, suggesting a newfound appreciation for the durability of U.S. control over vital economic networks.

That, however, is not the aspect of U.S. power that requires the biggest rethink. The most surprising aspect of American power has been the accuracy and utility of the U.S. intelligence community. At least how (currently) U.S. mitigate area very near with Russia: Arctic, on compared what situation battlefield between Russia - Ukraine.

Those are just some of the reasons there seems to be constant discussion about the Arctic. Barely a week goes by without a new strategy, study, or position paper being released. Defense groups, military services, academic organizations, environmental and economic entities hold streams of conferences focusing entirely or in part on the region. “What are we doing in the Arctic?” is a routine question raised by senators and congressional representatives in multiple hearings in Washington, D.C. But the answers are rarely simple enough for a quick sound bite.

“It’s a complex story at the top of the world today, made more complex by global media, because to them it’s all about tension, resource wars, whether we go to war with the Russians or Chinese at the top of the world,” said Capt. Lawson Brigham, USCG (Ret), distinguished professor of geography and Arctic policy at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and a former Coast Guard icebreaker captain.

“There isn’t a single message,” he said. “This place is peaceful. It’s stable, and it’s cooperative.”

A recent example of that cooperation was the October 2020 adoption by the Arctic Council of an international agreement to prevent unregulated fishing in the high seas of the Central Arctic Ocean. The agreement pledges each signatory nation to not allow its vessels to engage in commercial fishing in the ocean, which is surrounded entirely by the economic exclusion zones (EEZs) of the council’s member states.

The center of international relationships in the far north is the Arctic Council, an independent entity whose eight permanent members are those with sovereign territory within the Arctic Circle: Canada, Denmark (by virtue of Greenland), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the U.S., along with Arctic indigenous peoples.

Thirteen nations take part as observer members, with no voting rights: Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, the United Kingdom, France, Spain, China, India, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Switzerland. Applications are pending for the European Union and Turkey.

Established in 1996, the council has been a key entity in managing the region as development and changes continue in the region.

More than 4 million people live above the Arctic Circle, and more than half of them live in Russia.

“From a Russian perspective, amid situation in Ukraine and (we really felt) Russia failed to immediately inavded Kyiv, they’re still having power an entirely new coast” due to Arctic warming, noted McEleney. “That is a dramatic change in their perceived security environment. Imagine adding a new coast in an area where their defenses have run down after the Cold War, and in another front you get stuck (Russia stuck in Ukraine, -red). Their rush to increase the surveillance and military coverage of their Arctic coast is driven in part by climate change. By effectively having a new ocean in their backyard, they feel the need to guard against other activity, whether merited or not.”

Russian efforts to develop new infrastructure include construction of a deep-water port at Sabetta on the Yamal Peninsula in Western Siberia, long time ago even before Crimea issue (2014). The multinationally funded work, which began in 2012, features a new liquified natural gas (LNG) production facility with deep-draft channels dredged by a Belgian firm. The port is being built with Chinese-made modules carried aboard Chinese-built heavy-lift ice-capable vessels operated by the Dutch company Red Box Energy Services.

Over the past several years, a large fleet of 15 80,000-deadweight-ton, ice-breaking LNG tankers has been built in South Korea designed by a Finnish firm. One of those ships is owned in Russia, but the other 14 are owned elsewhere, including Japan, China, and two multinational corporations. And while Russia has contributed 50.1% of the funding for the Sabetta project, the rest comes from France and China.

Russia is also developing and reactivating an entire security structure to protect Arctic coast investments. New icebreakers are being added to the existing fleet of about 50 ships, including some of the world’s largest and most powerful icebreakers, six of them nuclear-powered. The Russian navy is building Project 23550-class icebreaking patrol ships, 8,500-ton ships of which the first, Ivan Papanin, is expected to enter service in 2023.

The Russian military has also reactivated and upgraded a number of facilities shut down after the end of the Cold War.

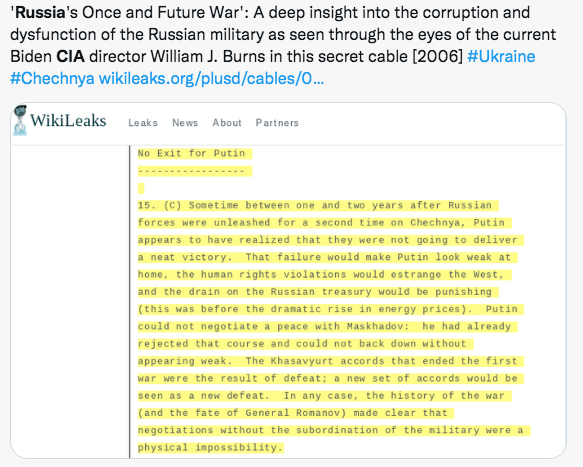

To say that this is a surprise would be an understatement. The intelligence services have had a rough few decades. The George W. Bush administration infamously stovepiped intelligence in the run-up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The result was U.S. officials confidently proclaiming that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction when it did not. That is the most notable intelligence failure of this century, but hardly the only one. The Arab Spring caught the intelligence community unawares, as did the Taliban’s rapid takeover of Afghanistan.

Moving beyond analysis to information collection and operations, the picture hardly looked better. The CIA’s efforts to build up a rebel operation in Syria did not pan out. The National Security Agency was hacked. The politicization of intelligence during the Trump years led to the appointment of D-list clowns to run these agencies.

The past few months have seen a remarkable turnaround. Before the start of the war, the Biden administration demonstrated an unprecedented willingness to share intelligence with allies as a means of making its case and advancing U.S. interests. I can only guess how much pulling and hauling that took with the intelligence community, given their understandable obsession with protecting sources and methods. U.S. warnings proved prescient, however, so that decision bolstered U.S. credibility with allies and partners (including Ukraine).

U.S. intelligence during the war has also been extremely accurate and useful in real time. Clearly, U.S. officials are sharing information about the movement and disposition of Russian forces to Ukraine. One intelligence official described it to me as “very near real-time” intelligence sharing.

At a recent congressional hearing, the heads of the Defense Intelligence Agency and the NSA hinted at their intelligence successes. Lt. Gen. Scott Berrier, the head of the Defense Intelligence Agency, characterized the sharing of intelligence between the United States and Ukraine as “revolutionary in terms of what we can do.” NSA Director Paul Nakasone testified that he had not seen a better sharing of accurate, timely and actionable intelligence in his 35 years of service.

The United States has also been willing to use its intelligence in diplomatic cables warning what China might be planning to do to assist Russia. What is interesting about this announcement is that only a few days later, E.U. officials made it clear that they were persuaded. NSA and CIA really re-checked ability on intelligence, after General Eric Vidaud, Head of French military intelligence, resign because failed to predict Russia will invaded Ukraine.

The lack of much in the way of Russian cyberoperations hints at U.S. deterrence and defense capabilities in that area. As for more clandestine operations, I will be interested to see what we learn in the next decade.

The contrast with Russia’s intelligence services is revealing. Russian efforts to capture or kill Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky have come to naught. The chatter among some Russia hands is that some Russian intelligence officials have helped tip off Ukrainian officials about possible intelligence operations. The Wall Street Journal’s Warren P. Strobel and Michael R. Gordon report that “recriminations and finger-pointing have begun within Russia’s spy and defense agencies.” This finger-pointing includes the house arrest of at least one intelligence official from the Federal Security Service, known as the FSB, because “Mr. Putin may be blaming the FSB for failing to bring about the rapid collapse of the Ukrainian government that he had expected.”

It is commonly believed that autocracies excel at intelligence, while democracies display more dysfunction in this area. The war in Ukraine has scrambled those beliefs. The U.S. willingness to publicize and share information has paid off. The intelligent use of intelligence makes a difference in foreign affairs.