Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s successful visit to Indonesia (he tweets 17 times just about visiting Indonesia) shows that he is ready to continue a cracking pace of diplomatic engagement as Australia faces an increasingly contested region.

Foreign Minister Penny Wong’s focus on Southeast Asia, coupled with an impeccable tone and messaging to Indonesia — delivered in Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesia language) — and her willingness to listen will be well received in Asia. Her equally masterful outreach to the Pacific nations coinciding with the Chinese foreign minister’s tour of the region has demonstrated that a good diplomacy delivered with humility and respect for Australia’s neighbors goes a long way in pursuing national interests.

While the diplomatic honeymoon will eventually end, the first 100 of the new government offers an opportunity to set a new tone for Australia’s engagement with the region. The former Prime Minister Scott Morrison described Australia’s international environment as “poorer, more dangerous and more disorderly.”

The fault lines between the United States and China continue to deepen. China’s support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and reluctance of many of our Asian neighbors to condemn it sets a dangerous precedent in our own region. When Albanese met Zelensky on July 4th, Albanese promised more military aid and sanctions against Russia. In the next few weeks we should start to get some sense of whether Ukraine can start to take the initiative & impose its own priorities on Russia rather than the other way round & how well the Russians are able to respond to the improvement of Ukraine capabilities.

While Albanese was largely continuing the previous government’s policies on Ukraine and China, in other areas his trip was about tidying up Morrison’s mess. His visit to Paris ended the diplomatic spat with French President Emmanuel Macron, caused by the clumsy cancellation of the French submarine deal. Albanese also used his trip to announce that after a decade of recalcitrance under the Coalition, Australia was back in the game of global action on climate change.

The message is important in its own right and it could also help stalled negotiations toward a free trade agreement with the European Union. While Albanese made exactly the right call by travelling to Europe, he must not waste time now that he has returned. He has plenty on his plate here in Australia.

Australia’s China problem – official contacts frozen and many of our exports under siege – is now gaining attention far beyond our shores. Much of the world, given stark evidence of the economic havoc that China’s displeasure can wreak, and of the ugly depths to which its “wolf warrior diplomacy” can descend, is trying to understand both how we fell into this hole, and whether we can climb out of it with our dignity intact. Common knowledge: The Australian Labor government, since 6 decades ago, has been more friendly towards Asia (not only Indonesia, not only China) than Liberal Party. Despite discussions surrounding a thawing of the tense Australia-China relationship, the future is still unclear.

Weeks ago before visiting Kyiv, Albanese was also in Madrid (NATO Summit). Regardless Labor is friendlier for Asia (and China), Albanese echoed sentiments with a warning that the strengthening of relations between Beijing and Moscow posed a risk to all democratic nations. “Just as Russia seeks to recreate a Russian or Soviet empire, the Chinese government is seeking friends, whether it be … through economic support to build up alliances to undermine what has historically been the western alliance in places like the Indo-Pacific,” he told. Albanese spoke to reporters after having a meeting on the sidelines with the leaders of Japan, South Korea and New Zealand – the “Asia-Pacific 4”.

“There we discussed the important focus of this NATO summit on the Asia-Pacific region. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has solidified the support amongst democratic countries for the rules-based international order,” he said.

How have Australia’s relations with China deteriorated so spectacularly? The short answer is that, although the most recent escalations have come from the Chinese side, for several years Australia has not properly managed the need both to get along with China and to stand up to it. When you ride two horses at once, you shouldn’t be in the bloody circus. China has been in the Pacific for a long time and wisely says Australia isn’t going to object to its “mere presence” but how China engages is vital. Pacific & PIF (Pacific Island Forum) should be focused on discussing security needs. In Order to preserve sovereignty, states should be free from coercion.

China is making an audacious attempt to muscle in on the Pacific's most important high-level gathering, pushing for a meeting with the region's foreign ministers on the same day leaders come together in Fiji for the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF).

Beijing has invited ministers from all 10 Pacific Island states it has diplomatic relations with to a virtual meeting with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi on July 14.

The timing is deeply contentious not also (after) Albanese and NZ’s Ardern join in NATO Summit in Madrid, but also (because) that is the same day Pacific leaders are due to hold their final retreat at the end of the Pacific Islands Forum meeting in Fiji's capital Suva. The PIF leaders meeting is particularly crucial this year because it is their first in-person gathering since the pandemic hit in 2020. They last met face-to-face in Tuvalu in 2019.

The forum is also hoping to use the meeting in Fiji to heal a damaging internal split over leadership after a small group of leaders struck an interim deal in Suva earlier this month.

It has already moved to postpone a formal in-person dialogue with PIF dialogue partners — including the United States and China – partly because some Pacific representatives do not want intensifying geo-strategic competition in the region to weigh too heavily on the meeting in Fiji. But (at least) two Pacific Island states were pushing back against the Beijing proposal because they did not believe the timing was appropriate.

Pacific Island foreign ministers last met the Chinese minister just one month ago, when he hosted them for a virtual meeting from Fiji in the midst of a long Pacific tour. Mr Wang was forced to shelve a sweeping regional economic and security pact with the Pacific in the wake of that meeting after some countries raised concerns.

Australia’s huge economic dependence on China – the market for more than one-third of our exports, far more than the United States or any European country – gives us no choice but to get along with our larger regional neighbor. It is fanciful to think we can find alternative markets on that scale any time soon, or perhaps ever.

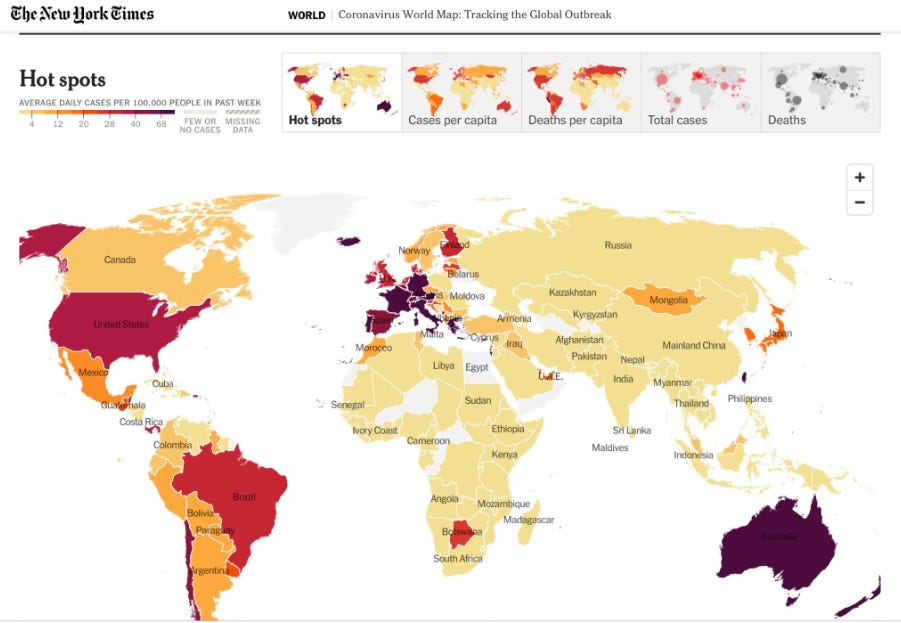

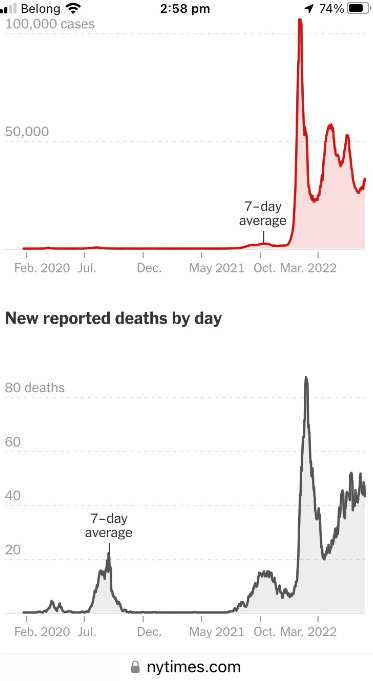

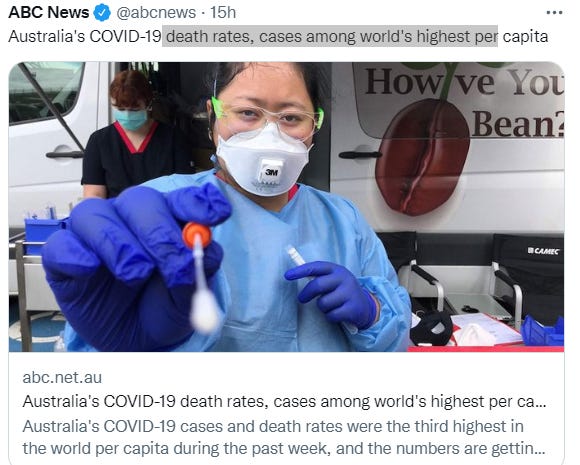

The global economy is under stress with high inflation, supply chain bottlenecks, and rising energy, commodity and food prices. COVID-19 is persistently present in Asia. The region is facing immediate impacts of climate change.

Still, even in such challenging times, Australia’s neighborhood is showing the strongest post-pandemic economic vitality. Regional mobility is back. Asia is learning to live with COVID-19. And competition between China and the United States need not lead to war.

Australia has been responding to these new realities. The past three years have seen a reorganization of our foreign policy in the face of the growing challenge from China, with a lot mess legacy by Morrison, honestly.

Australia should expect this to continue through policies aimed at building resilience and sovereignty, deepening our alliance with the United States, and preserving a rules-based order and balance of power in Asia. These are the tenets of Australia’s Indo-Pacific strategy, first articulated in the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper and subsequently strengthened by the Morrison government.

The Albanese government has been clear that while there will be continuity in many areas of foreign policy, it will put its own stamp on Australia’s engagement in Asia. There is an opportunity now to present a positive vision for Australia’s future in Asia that resonates with our regional partners and is accepted by Australian people, who are clearly concerned about mounting global challenges, such as climate change and a weakening global economy.

This cannot be done if Australia frames its approach to Asia solely through the lens of competition with China. Anthony Albanese must be more than a national security prime minister.

One way the government can frame 21st century Australian foreign policy is to anchor it in the concept of a shared region, where Australia is an active member and a responsible citizen shaping the security and prosperity of the region, in tandem with its regional partners.

A shared region means maintaining open trade and economic connectivity. Asia is facing a bifurcation of technologies, rules, and standards, caused by partial U.S.-China decoupling and economic nationalism. But it remains in the interests of Australia and our partners in Asia to promote an open, rules-based economic order, while protecting Australia economics from coercion and over-dependencies on China.

A shared region means a shared responsibility for security in Asia. It means recognizing that many of our most important partners in Asia don’t want to choose between the United States and China. Nor do they want to be viewed simply as pawns in a new “great game,” as we saw last week when Pacific leaders rejected China’s proposal for a regional security and economic compact. Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo reinforced Indonesia’s unwillingness to be drawn into either side of the U.S.-China competition: China is noticeably absent in the Jokowi-Albanese Joint Leaders Statement. Kevin Rudd, former PM and same Labor with Albanese, described Indonesia as “(Australia’s) our most important neighbour”.

A shared region means confronting pandemics, economic inequality, and climate change together. Wong’s acknowledgment last week of the centrality of the climate change threat to Australia and our Pacific and Asian neighbors resonates strongly with our near neighbors. A substantive increase in the Australian aid budget will also reaffirm our credentials as a committed regional citizen.

Finally, a shared region is shaped by people. As a champion of migration, tourism, education, and professional mobility, Australia must rebuild its reputation as a welcoming and open country, empowered by a flow of students and scholars, migrants, tourists, and professionals from the region.

Deepening our Asia capability is the final piece of a shared region vision. To be a part of the region requires a deep understanding of countries, people, and systems in Asia.

Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade did not comment directly on Beijing's proposal for PIF, simply saying: "Australia looks forward to participating in the Pacific Islands Forum leaders meeting." "We respect the right of our Pacific partners to choose with whom they engage and how," they said.

The controversy comes as strategic competition continues to intensify in the region. Over the weekend, Australia signed up to a new "Partners in Blue Pacific" initiative with the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan and New Zealand. The five countries are vowing to coordinate their efforts in the region more effectively and intensify efforts to tackle a range of issues ranging from climate change to illegal fishing.

The challenges facing Australia are formidable. To navigate them, Albanese must accept responsibilities shared region and commit to keeping it secure, prosperous and thriving, together with Australia neighbors.

Can Anthony Albanese be the first Australian leader to put the debate about his nation’s place in Asia to bed, by placing Australia — once and for all — at the heart of a shared region, at least with Jokowi, “the most important neighbour of Australia, and (at least) to balancing influence of China (and also U.S.) in entirely Pacific?