Berdikari (Nationalism Resources) Restart From Jokowi: A Global Trend Amid Electric Vehicle and CHIPS Act

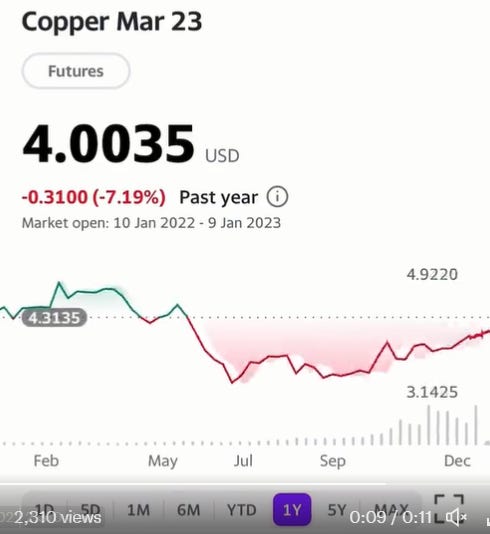

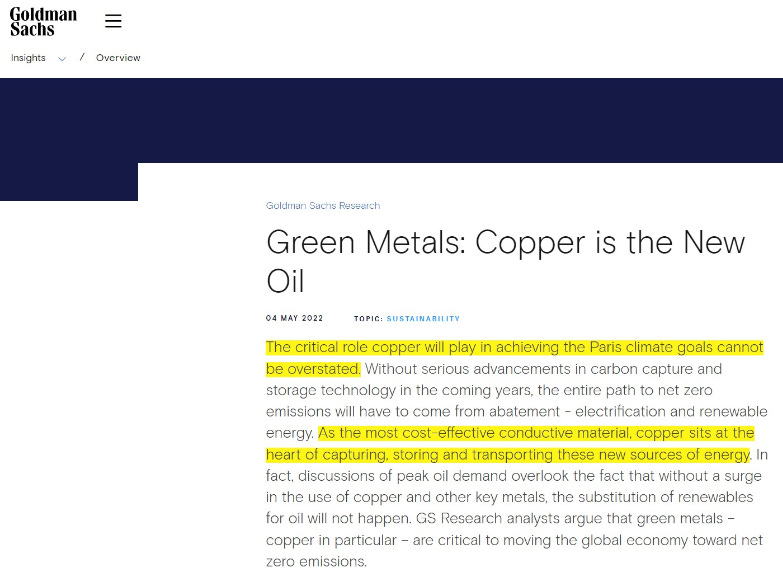

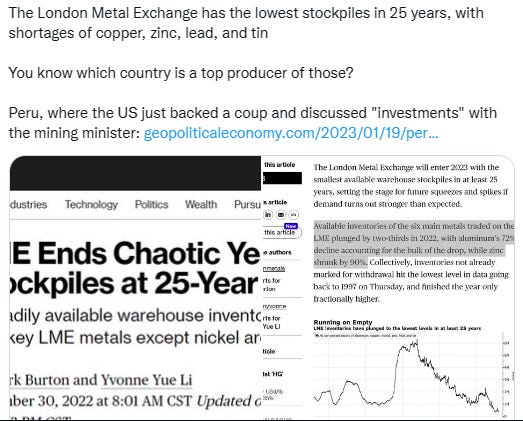

Jokowi aims to process nickel and bauxite in the country (& hour ago, announced a new target: copper, in celebration of 50 years anniversary Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P)), which is really similar to Zimbabwe, Nigeria (maybe Ghana will follow) since this week. The price of Copper now $4/lb back in June before the markets unraveled.

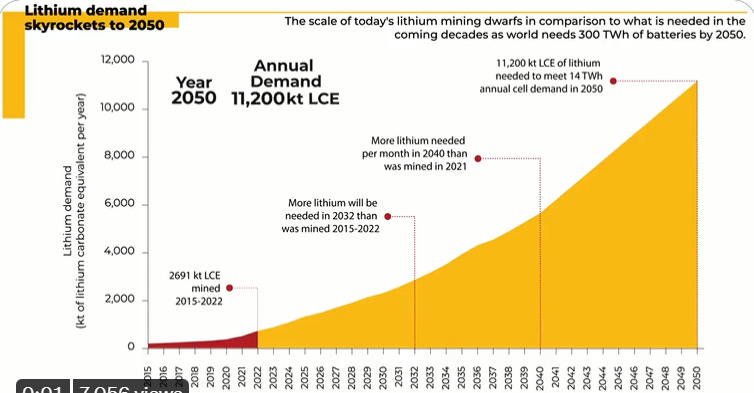

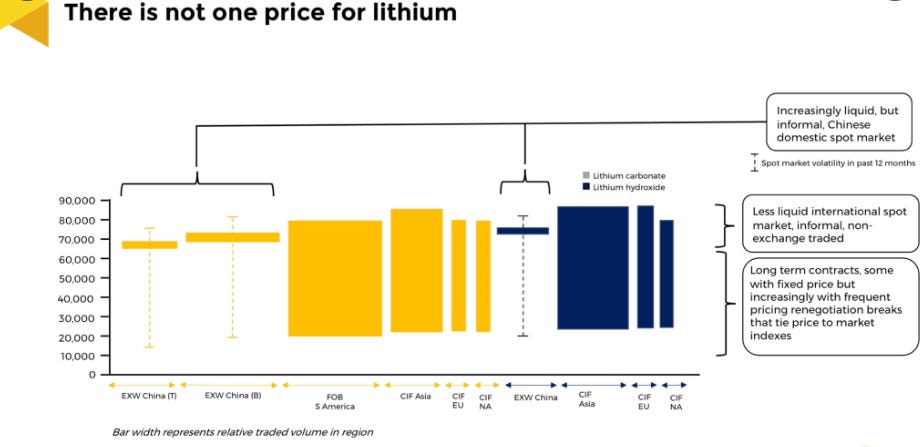

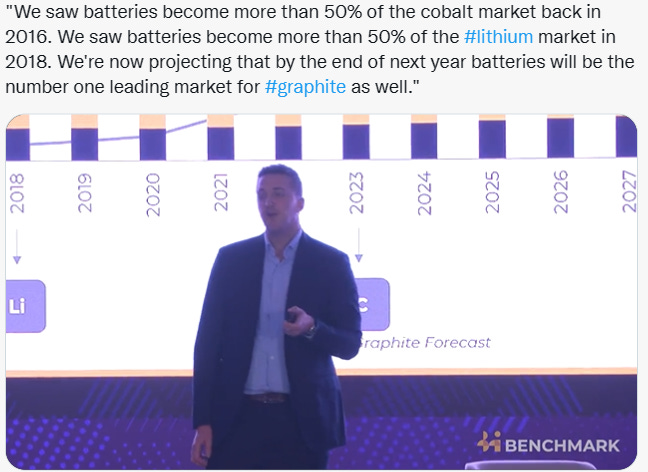

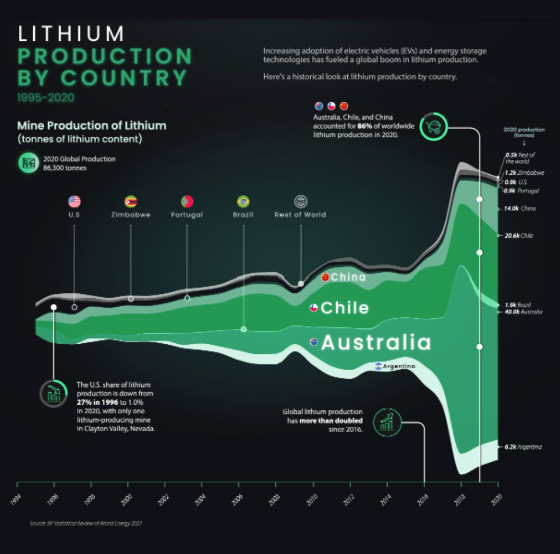

Nigeria recently discovered large deposits of Lithium, an essential component for building batteries for electric cars, laptops and mobile devices. Elon Musk showed interest in signing a trade partnership with the Federal Government Nigeria for the mining of Lithium. Nigeria Minister of Mines and Steel Development, Olamilekan Adegbite, rejected the offer. The Minister stated that Nigeria would only deal with Tesla if the company agreed to build its battery-making factories in Nigeria. The price of Lithium has risen from $6,000 per tonne in 2020 to $78,000 per tonne in 2022, and it is expected to be the most valuable mineral on earth by 2040. The worldwide for even exploration and mining starts from 0.4 per cent lithium oxide but when started exploration and mining, one per cent up to 13 percent lithium oxide content.

Senior official in the Iranian Ministry of Industry, Mine and Trade (MIMT) said (Feb 27th, 2023) that a deposit located in the western province of Hamedan contains some 8.5 million metric tons of lithium ore, PressTV, Iran’s state-owned news network, reported. With this discovery, which would make it the world's second largest lithium reserve after Chile.

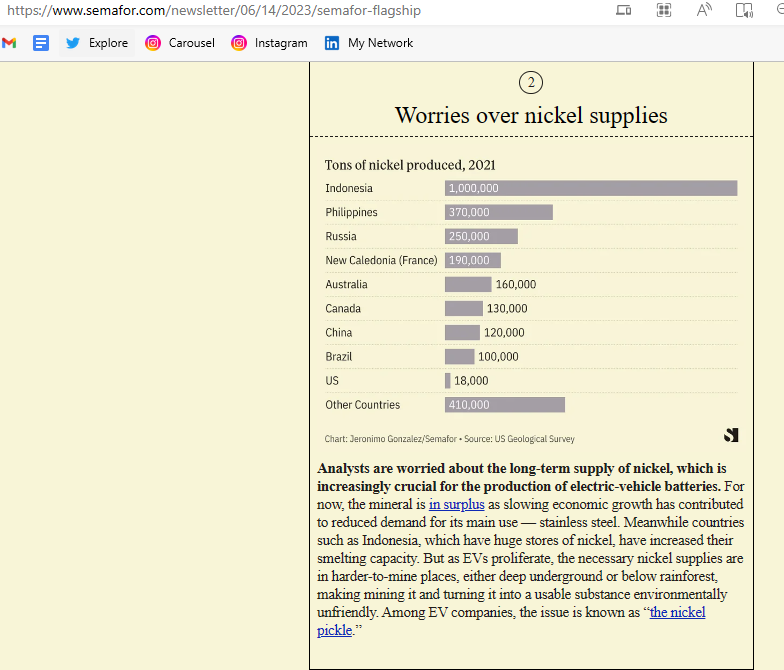

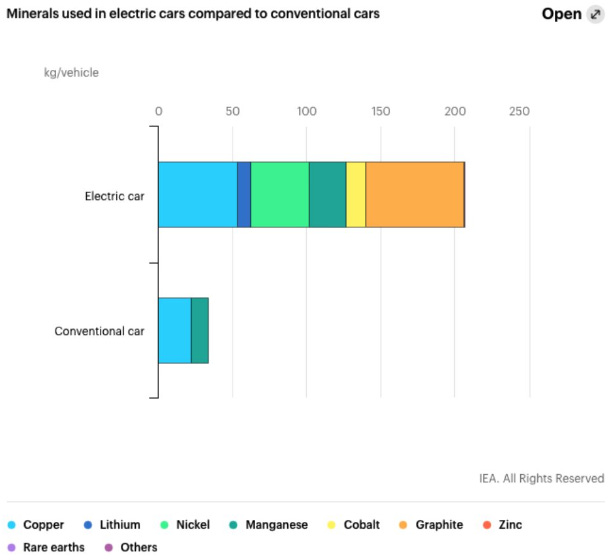

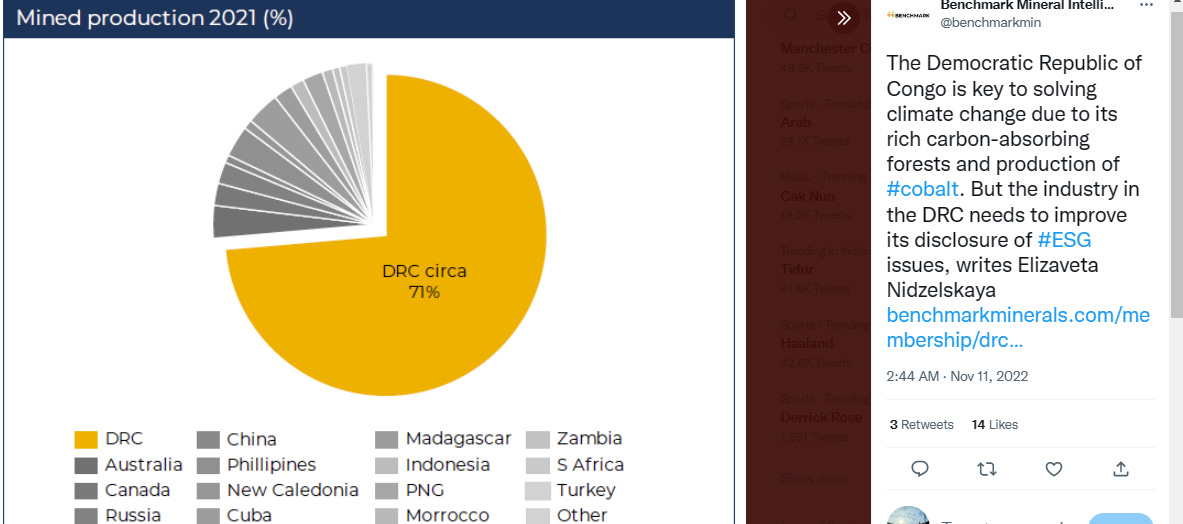

Demand for metals could spike hard from copper to lithium, nickel, and more while China really reopened again, full-open, after Covid restriction. China's role in the battery supply chain is crucial to the energy transition, yet many fear such a heavy concentration. The Nickel ban is seen by many as a potential turning point in Indonesia’s attempts (and other countries with rich-mineral deposits) to harness resources to boost industrialization and fight poverty. Jokowi send directly Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi, to facing WTO. H.E. Retno was Indonesia ambassador to the Netherlands, already similar about the dispute. Zimbabwe, Nigeria, and Ghana are borrowing a leaf from Indonesia’s playbook to ban unprocessed exports of minerals.

Over the past 5 years Lithium and Nickel prices rose 255% and 138% respectively. Bloomberg reports that half of all car sales could be electric vehicles by 2030, up from just 9% last year. Jokowi at least, in three summits (G7 Summit in Berlin last June-Jokowi as a Special Guest because host G20; G20 Summit in Bali, and EU-ASEAN Summit) explained very carefully Indonesia's aims to locally manufactured batteries, to resource nationalism.

Additionally, increased commodity prices have created an impetus for governments to try to reap profits from these minerals. The specter of resource nationalism has once again gained a foothold. Increasingly valuable minerals that are key to the new green economy quickly gaining momentum across the world. new push for governments to exert more control over these resources.

Why China (always) leaning to Indonesia

Indonesia and other countries are trying to control the exploitation of valuable commodities such as nickel, bauxite, lithium, diamond (in Botswana). Ghana just discovered Lithium. Smells like a new wave of resource nationalism. as the supply-chain crisis appears to be stabilizing. Will Indonesia, Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Ghana, other countries decide to usher in a new wave of resource nationalism as other countries move to protect their raw resources from foreign exploitation? Lithium’s medium long term price will keep every resource development project in economic play Short term price decreases (as now), increases will be the norm, but green light for incentive price will be on. Deciding where to put money becomes more challenging than in past.

Such events demonstrate how the global commodity market for everything from oil to semiconductors is changing. With new semiconductor manufacturing plants in the United States (CHIPS act, try to minimize U.S. reliance on China about semiconductors) and the slow but steady de-dollarization of the international oil trade, the commodity trade is transforming quickly. The CHIPS Act is intended to jumpstart the U.S. onshore industry to support advanced semiconductor manufacturing.

Example, the latest case U.S. appeals court reversed a decision that allowed Chinese networking-device maker TP-Link Technologies Co to move a patent lawsuit against it from East Texas to California federal court. Tata Group is close to taking over a major plant in India in a deal that would give the US its first homegrown iPhone Apple Inc., with the goals to minimize Apple’s reliance from China’s supply.

(rare earth in Afghanistan)

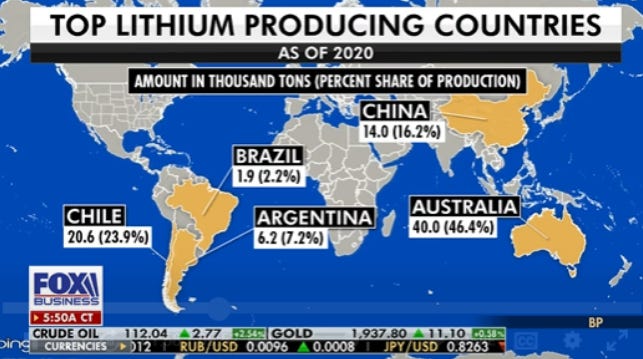

Zimbabwe has banned all lithium exports. Zimbabwe says it's losing $2.5b by exporting raw mineral and not processing lithium and making batteries in-country. Zimbabwe is estimated to have the largest unexploited reserve of lithium in Africa and is the sixth-largest producer in the world. It has enough to supply 1/5th of the world’s needs. Data by Business Insider, Australia produced about half the world’s lithium in 2021, with Chile’s and Argentina’s output making a combined 30% of the total and China responsible for some 13%. Zimbabwe produces just 1% of global output, just behind Brazil.

Instead of exporting raw lithium, Zimbabwe hopes to locally manufacture lithium batteries. Nigeria also wants to process lithium locally, and refused an offer for it to be mined for exportation. Zimbabwe already started the Sabi Star Lithium Mine, and President Zimbabwe Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa visited this site last December. African Lithium Resources (Pvt), a subsidiary of Alternative Investment Market-listed Red Rock Resources, said it will be focusing on developing its recently acquired Tin Hill lithium resource in Bikita into a small-scale lithium operation beginning this month. Bikita mine contains the largest-known deposit, ~11 million tonnes.

Zimbabwe is also facing a new problem, looting and transportation by illegal miners and dealers from some recently discovered lithium deposits continues. This is really similar to Indonesia. The high price of lithium has recently attracted a slew of miners targeting abandoned mines in search of rock that might have some lithium. The rock is then exported to other countries. The new laws are designed to stop this activity as well. Some illegal miners push selling mineral deposits directly (with no more process) in the global market, and this (illegal miners) has been a painful problem since years ago, like the cases near the site of Freeport-McMoran, now Freeport Indonesia. And Jokowi has tried to create the same law since years ago, to stop illegal activity as well.

The track record of other countries attempting this approach to resource nationalism isn’t great. Chile, home to the world’s largest known lithium reserves, has tried and failed to deepen its lithium manufacturing capacity over the past decade. While Chile hasn’t banned the export of lithium, it hasn’t fully succeeded in building up its own processing power. The result has been a steady government increase in royalty levies on foreign producers operating in the country. Regardless of viability, resource nationalism will be a central theme in 2023. But Chile tries to repair policy. The recent election of Chile’s new center-left president, Gabriel Boric, has emboldened this new resource nationalism in all the countries in the Lithium Triangle, plus Peru, also home to vast mineral resources, such as copper.

All four countries now are led by more ideological leaders who support greater government intervention in the economy. There is even talk about the creation of an OPEC-like “lithium cartel,” and according to experts, the lithium market may quintuple over the next 35 years.

In Chile, newly elected President Gabriel Boric Font has proposed the creation of a national lithium company, and news reports indicate that some of his advisers are concerned about a lack of a national lithium policy. Already, some left-of-center parties in President-elect Boric’s coalition have sought court injunctions to halt new private bids to mine lithium.

In Peru, President Pedro Castillo is pushing for increased mining royalties and has taken a hands-off approach to the increasing social conflicts in the country’s mining regions. It’s a clear signal that his government is far more interested in supporting community concerns than defending the interests of mining companies. In Argentina, the government is developing a new mining strategic road map with Lithium as a key part. Its administration is considering policies that include “analyzing investment incentives for lithium mining, including a possible exemption for profit repatriation … and a system of ‘progressive’ export taxes to charge lower rates at the start of a new project.”

One particularly Argentine wrinkle is that, according to the country’s constitution, provinces own the natural resources located in their territories. This makes it harder to claim federal control of mining activities, but still leaves plenty of levers to influence the sector.

At the heart of this renewed resource nationalism in the region are the minerals key to high tech products and a growing green economy.

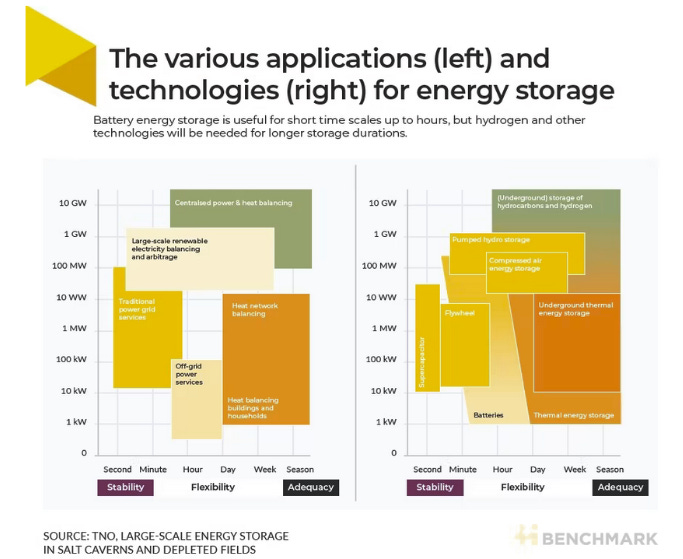

Minerals such as lithium, copper and zinc are key to the development of future technologies such as electric vehicle batteries, solar panels and wind turbines, as well as energy storage batteries. As demand for these green economy technologies grows, so too does the need for these key minerals. Renowned energy expert and author, Daniel Yergin, echoed the emergence of Latin America as a leader in raw materials, necessary for this new economy, stating that Latin America is “a major, major source of lithium, a major source of copper. Those are two of the critical elements in the energy transition. … But you also have across Latin America a wave of populism.”

Argentina, Bolivia and Chile are at the heart of this new mineral revolution. The countries form the Lithium Triangle, which analysts believe contains over half of the world’s lithium reserves.

Bolivia’s lithium reserves are considered the world’s largest at 21 million tons; Argentina is not far behind with nearly 15 million tons; and Chile has close to 9 million tons. Mexico is also in the lithium business. Recently, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), called for lithium deposits to be reserved for state exploitation and kept away from foreign investors. Mexico is already home to at least one large lithium deposit in the state of Sonora, which notably was exempted from the presidential declaration and allowed to move forward under a Chinese corporation.

As the global economy recovers from the supply-chain crisis of the immediate post-pandemic period, new challenges have emerged concerning the technology and raw materials that make our devices (and thus the world) function.

This will be profound in the manufacturing of semiconductors, confined mainly to Taiwan, but will soon expand in deeper ways to the US and perhaps even Europe. As developing nations continue to struggle with the strong US dollar and hawkish US Federal Reserve, we are bound to see more efforts to control raw materials vital to the economy, including lithium. The raft of measures (CHIPS Act) could amount to the biggest shift in U.S. policy toward shipping technology to China since the 1990s. If effective, they could hobble China's chip manufacturing industry by forcing American and foreign companies that use U.S. technology to cut off support for some of China's leading factories and chip designers.

Specific for Freeport. After about two years of intensive negotiation processes involving the government, PT INALUM (Persero) Mining Industry Holding, Freeport McMoRan Inc. (FCX) and Rio Tinto, finally today the transfer of PT Freeport Indonesia's (PTFI) majority shares to INALUM has been officially transferred. The official transfer of the shares was marked by the issuance of the Production Operation Special Mining Business License (IUPK) in lieu of the PTFI Contract of Work (KK) which had been running since 1967 and renewed in 1991 with a validity period of up to 2021. With the issuance of this IUPK, PTFI will obtain legal certainty and certainty of business by pocketing an extension of the 2x10 year operating period until 2041, and obtaining fiscal and regulatory guarantees. PTFI will also build a smelter within five years.

In another push to develop downstream mineral industries, Jokowi also announced an export ban on washed bauxite to come into effect in June of this year (Jan 6t). The ban was supposed to have been put in place years ago but did not materialize because of the country’s inability to build smelters to process the ore, from which aluminum is extracted. Local businesses and investors had been reluctant to build the pricey facilities and were content with the profit from washing the silicates from the raw ore.

This is a classic problem for the country when it comes to commodities. A lack of investment and skilled human resources has trapped Indonesia in the role of a provider of raw materials for the global supply chain. And for decades, this has been quite convenient for industrialized and developed countries, which possess the technology, investment and human resources to produce high-value goods.

When Jokowi announced a nickel ore export ban three years ago, followed by export prohibitions on tin ore and other minerals, resistance from other countries mounted. The European Union brought the case to the World Trade Organization, which found Indonesia guilty of breaching global trade rules. With the President’s insistence on processing minerals at home, it is likely that Indonesia will face more lawsuits in the future. But Indonesia’s policies are no great departure from common international practice; the United States and China also engage in protectionism to develop local industries.

The Observer in Zimbabwe says facilities will cost hundreds of millions of dollars and it could take two to three years before they can get up and running. Jokowi will face the same obstacle at least 2-3 years to manufacture nickel (& next, chopper). Companies must either set up local processing plants or provide proof of exceptional circumstances – and receive written permission from the government – before lithium can leave the country.

The export ban of raw or minimally processed Lithium, Nickel is part of a broader trend of lithium, nickel and other critical mineral producing countries demanding that more processing take place in the country. something to watch along with who does labor, environmental measures. Lithium and nickel is becoming a key mineral worldwide. Its demands surging for use in the ceramic industry, mobile phone manufacturing and making of automotive batteries.

Back to Indonesia. The recent decision of the panel of the World Trade Organization (WTO) Dispute Settlement Body against Indonesia’s policy of banning raw nickel export should not in any way distract the government’s focus on its well-designed strategy to develop the processing of nickel and other minerals in the country.

The government should instead appeal against the verdict of the panel which ruled in favor of the European Union’s complaint that the Indonesian raw nickel export ban imposed since January 2020 violated WTO rules. Indonesia, as a sovereign country, shall abide by the 1945 Constitution, which stipulates that land, waters and natural resources are controlled by the state and shall be managed and used to the greatest benefit of the people. Processing nickel within the country will optimize the value added of that mineral.

True, Indonesia, as a member country of the WTO, must also abide by WTO rules, but many of these multilateral trade watchdog rules are often subject to different interpretations in line with the national interests of its members, as exemplified in the case of the raw nickel export ban. The export ban has been welcomed by many of the international business communities as evident in the tens of billions of dollars of foreign investment pouring into the nickel refining industry in Indonesia over the past three years.

The number of nickel processing plants has more than doubled from 10 in 2014 to 21 in 2022, according to the Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry. A dozen more refineries are under construction mostly in Sulawesi and the Halmahera islands. The export ban also has catapulted refined nickel export earnings from US$1 billion in 2014 to almost $21 billion last year. The nickel industry development has dramatically expanded on the back of the rising international demand for electric vehicles (EV) as part of the global campaign to reduce fossil fuel consumption. As nickel provides 60 percent of the materials for car batteries, global demand for refined nickel – formerly used mostly in the steel industry – will exponentially increase due to that mineral’s key role in the energy transition. Hence, as the world’s largest nickel producer and the country with the biggest nickel reserves, it is commercially and environmentally viable for Indonesia to develop production capacity along the EV supply chain.

The nickel strategy has become part of the country’s goal to build an integrated EV supply chain, from mining and processing to battery production and eventually EV manufacturing. The worst-case scenario if Indonesia loses its appeal will require the government to revoke the raw nickel export ban. But even if this ban is lifted, nickel mining firms would not automatically export most of their nickel ores because most are tied up with domestic processing/smelting companies.

The government also can discourage export through WTO-compatible measures – imposing tax on raw nickel exports – to secure adequate supplies of raw nickel for the processing industry. Most important, though, is for the government to develop the ecosystem for renewable energy to power the mining and processing of nickel and infrastructure for tailings disposal, otherwise environmentally conscious consumers will shun car batteries or EVs made in Indonesia.