Keffiyeh Palestine as a witness: How Kherson is “critical point” General Armageddon vs Ukraine contra-intelligence

Since October, Putin finally deployed “General Armageddon”, Sergei Vladimirovich Surovikin. The brutal general, already “successful” in Syria and a lot of battlefields. Then, Kyiv tried to slow down them and entire Russia’s military.

After weeks of fighting for scraps of territory on the war’s bloodiest front, Oleh, a 21-year-old Ukrainian company commander, was summoned suddenly last August, along with thousands of other soldiers, to an obscure rendezvous point in the Kharkiv region.

At his last position, relentless Russian artillery fire had stalked his men’s every step. But here, in a patch of villages, farmland and streams in Ukraine’s northeast, the quiet was deeply alarming. “The silence bothered me the most,” Oleh said. “It seemed off. How could this be?”

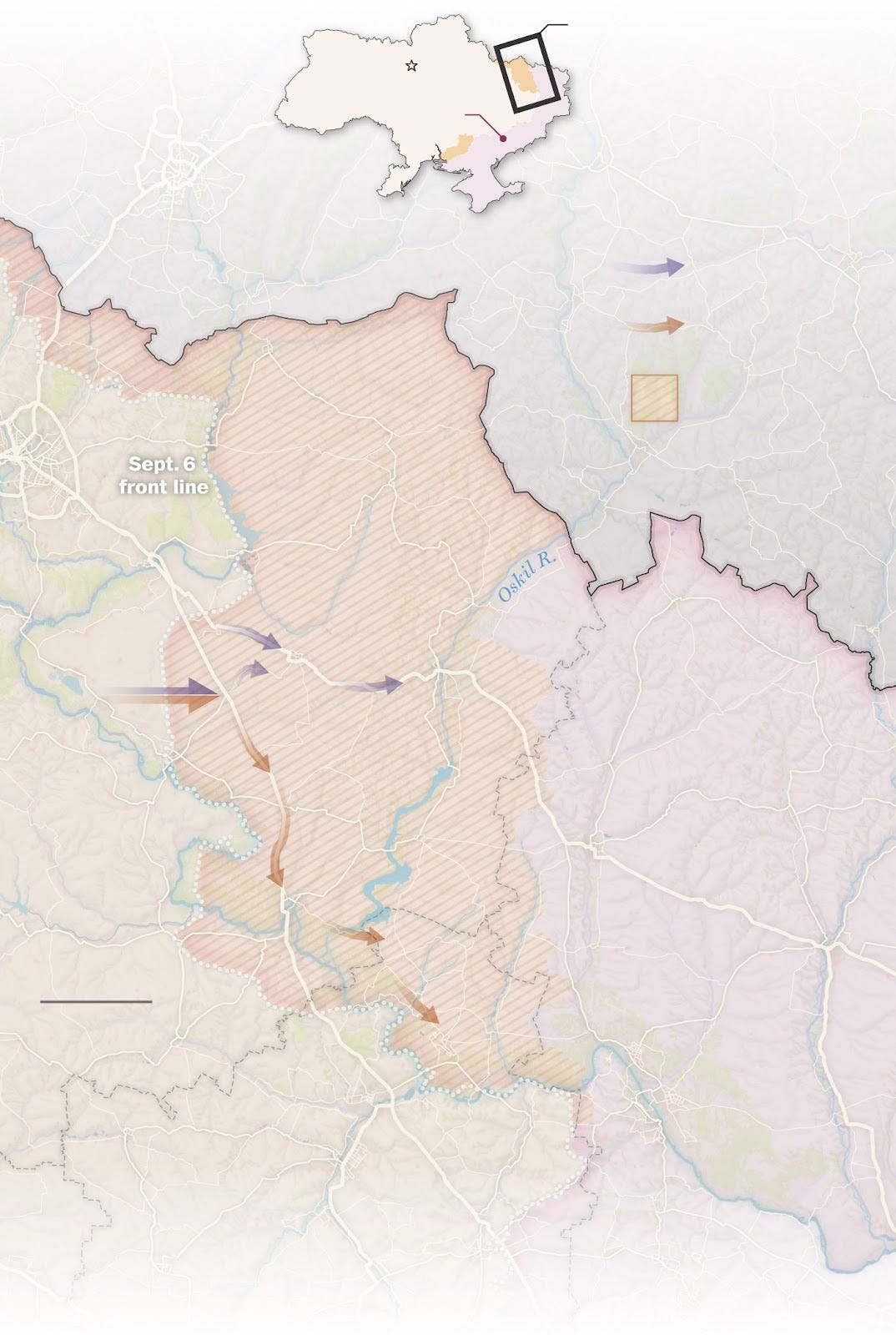

Even more unsettling were the orders his superiors handed down: to charge as far as 40 miles into enemy territory at high speed in an audacious, top-secret counteroffensive — directly between the Russian-occupied stronghold of Izyum and Russia’s own Belgorod region dotted with military bases. It seemed preposterous. “Some kind of dubious operation,” Oleh said.

But after a summer of heavy Russian casualties and President Vladimir Putin’s refusal to conscript reinforcements, the Kremlin’s troops were badly depleted. A shift of units south — to defend the captured regional capital of Kherson amid talk of a big Ukrainian push there — had left the Kharkiv area exposed.

It was a stunning vulnerability, confirmed by Ukrainian reconnaissance teams and small drones. And Kyiv would exploit it to change the dynamic of the war, and achieve Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s goal of redrawing the battlefield map before winter.

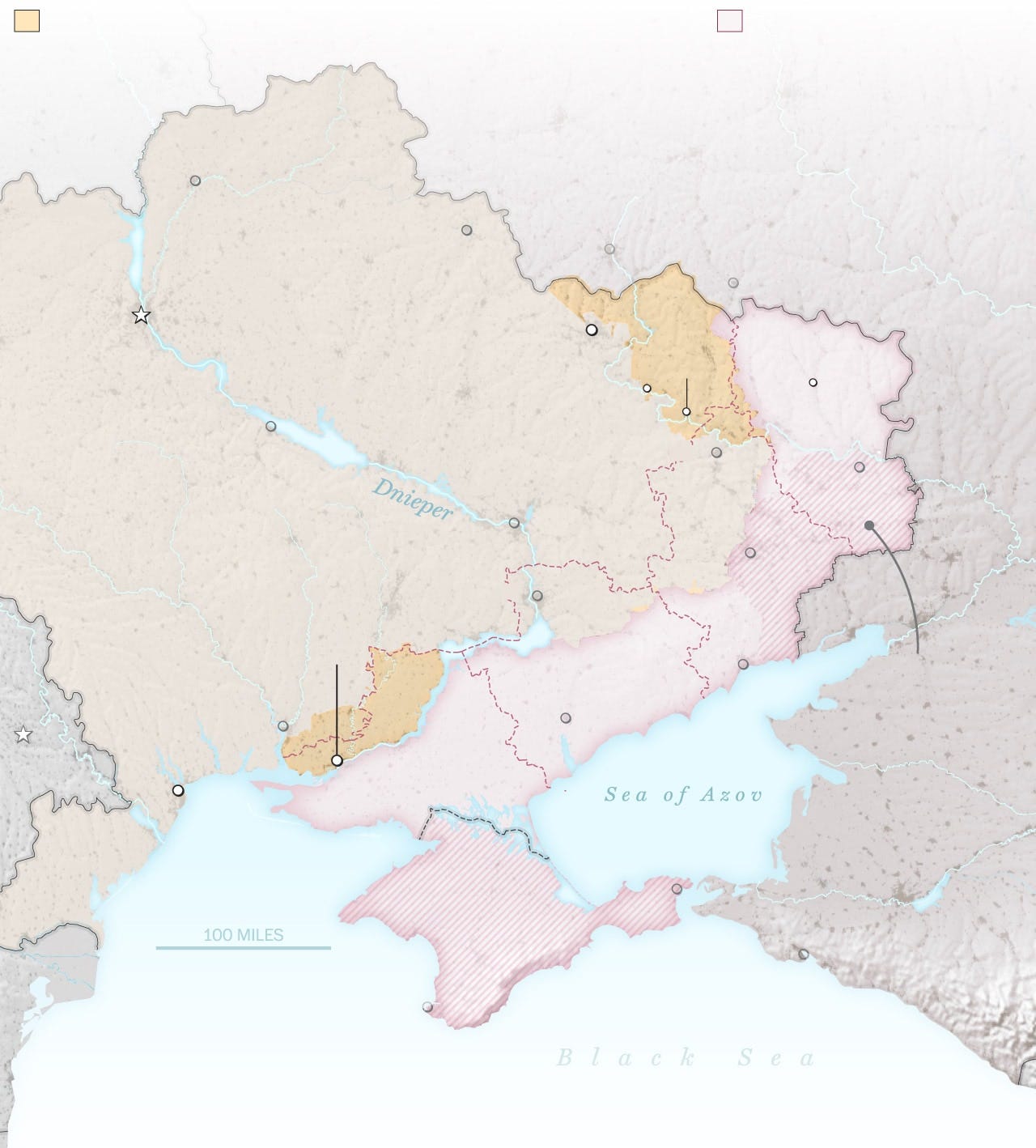

After Russia’s invasion began on February 24th, Ukrainian troops forced Russia’s retreat from Kyiv in an underdog triumph that ended the first stage of the conflict. Thwarted from conquering the capital, Russia concentrated its power in the south and east, pummeling Ukrainian forces until new, longer-range weapons arrived from the United States and Europe and helped stall Moscow’s advances. Ukraine had survived but, after a half-year of war, one-quarter of its territory was still occupied and its military had failed to show it could launch an offensive to retake substantial ground.

That was about to change.

In early September, Ukrainian forces would steamroll across hundreds of square miles, routing the Russians and surprising themselves. The Kharkiv offensive revealed the inability of an undermanned and underequipped Russian force to hold territory across a vast front. It shocked the Kremlin, and it proved to Ukraine’s supporters that they were not wasting billions in weapons and economic aid.

Putin was forced to conscript hundreds of thousands of men, making the costs of war clear to a Russian population that had isolated itself from its leader’s “special military operation.” The mobilization set off unrest but was too late to stop Ukraine’s momentum from spreading south to Kherson, where, after hard combat and significant losses, Kyiv’s forces in November recaptured the only regional capital that Putin had seized since the start of the war.

This reconstruction of the Kharkiv and Kherson counteroffensives is based on interviews with more than 35 people, including Ukrainian commanders, officials in Kyiv and combat troops, as well as senior U.S. and European military and political officials.

What emerges is a story of how deepening cooperation with NATO powers, especially the United States, enabled Ukrainian forces — backed with weapons, intelligence and advice — to seize the initiative on the battlefield, expose Putin’s annexation claims as a fantasy, and build faith at home and abroad that Russia could be defeated.

“Our relationship with all of our partners changed immediately,” said Col. Gen. Oleksandr Syrsky, who commanded the Kharkiv offensive. “That is, they saw that we could achieve victory — and the help they were providing was being used with effect.”

In the last days of August, Syrsky met in a large operations room in Ukraine’s east with his top aides and key brigade commanders. Before them was a 520-square-foot 3D-printed terrain map of the part of the Kharkiv region occupied by Russia.

Each commander walked the path of his unit’s planned assault amid the replica cities, hills and rivers, acting out its mission and discussing coordination, contingencies and worst-case scenarios. Officers used laser pointers to spotlight trouble spots.

“It was painstaking work,” Syrsky said.

Since at least the spring, Syrsky had been considering the Kharkiv region, and the strategic cities of Balakliya and Izyum, as vulnerable points for the Russians.

He started thinking about how he would conduct an offensive by driving deep into Russian-held territory from an unexpected area north of the two cities, cutting off Russian forces from reserves across the nearby border and putting both Balakliya and Izyum at risk of encirclement.

The geography and the positioning of Russian forces convinced him it could be accomplished in a single, rapid blow — ideally so fast that Russia would not be able to regroup.

When orders went out from the Ukrainian General Staff last summer for commanders to come up with possible diversionary operations to draw Russian forces away from the defense of Kherson, Syrsky knew what he would propose.

“The enemy … thought that, because so many forces had been built up in Izyum and more were stationed over the Russian border in the Belgorod region, ‘you’d have to be crazy to move and try to strike right in the middle and split the two,’” Syrsky said. “But the thought was there.”

In the early stages of the war, Russia had converted Izyum into a military stronghold, eyeing the city as the base for a pincer movement that would surround Ukrainian forces in the east. At the height of its preparations, according to Syrsky, Russia had amassed 24 battalion tactical groups — about 18,000 troops — in Izyum and surrounding towns, along with stockpiles of weapons and ammunition.

By August, in part thanks to detailed intelligence supplied by the United States, Syrsky saw that the number of battalions in Izyum had dropped by at least half, as Russia relocated its most experienced fighters to Kherson.

“In the history of wars, there have been many cases when an attack on a diversionary axis — that is, on a secondary axis — turns into the main axis,” Syrsky said. “The prospects were all there, because … the enemy absolutely didn’t expect that we would attack in the exact place where we delivered the main blow.”

Syrsky calculated that Ukraine could not afford the losses that would come with attacking towns and cities head-on. Instead, he planned to sweep across the front, encircling population centers and forcing the enemy to retreat.

Speed was essential. If the Russians sent in reserves from across the border, large numbers of Ukrainian troops could get cut off behind enemy lines.

“Everything depended on the first day — how far we could break through,” Syrsky said. “The farther we went, the less they could do, the more their units would be cut off and isolated under psychological pressure.”

By August, the Ukrainians had all but run out of the Soviet-era ammunition used by most of their artillery. Western allies were rushing in NATO-standard ammunition and systems — but not enough.

In a risky decision, Ukraine moved some of the most valuable Western weapons systems away from hotter spots on the eastern front. Each attacking brigade was armed with at least eight M777 howitzers, commanders said. In some cases, the M777s arrived at encampments the night before the assault began. Extra drones were also brought in to ensure that brigades could pinpoint targets and use less ammunition.

Maj. Gen. Andriy Malinovsky, head of missile forces and artillery training for the Ukrainian army, was still worried the force could need more than 100,000 munitions. The Ukrainians had only tens of thousands — not enough for a protracted slog. (Ultimately, Malinovsky said, they used about 32,500 over five days).

U.S. intelligence helped ration the ammunition through accurate targeting. After many months, according to U.S. and Ukrainian officials, the two partners had worked out a real-time regimen: The Ukrainians would outline the types of high-value targets they were looking for in an area, and the United States would use its vast geospatial intelligence apparatus to respond with precise locations.

The Americans, however, were not deeply involved in planning the Kharkiv offensive and learned about it relatively late, according to U.S. and Ukrainian officials.

Despite attempts at secrecy, the Russians eventually realized that the Ukrainians were up to something.

Thanks to Russian bureaucracy, Syrsky said, the information “didn’t reach anyone or it wasn’t taken into account.”

At the Pentagon, officials suspected that Russia’s leadership didn’t fully realize the vulnerabilities on the Kharkiv front because battlefield commanders were lying. Another hypothesis, a senior U.S. defense official said, was that Russia saw the onslaught coming but didn’t have enough men to stop it.

The Ukrainians moved pontoon bridges around, hoping to trick the Russians into expecting a direct assault on Izyum, rather than a drive deep into territory some 30 miles northwest.

By mid-August, Syrsky was confident the plan would work — but he needed to sell it to Zelensky. He described the mission as a chance to liberate a large swath of territory with minimal resources and losses.

Zelensky, craving a big battlefield win, approved the attack.

On Sept. 6, just past 3:30 a.m., Oleh’s company of about 100 soldiers, part of the 25th Airborne Assault Brigade, began to advance in small columns of three infantry fighting vehicles each. For hours before they started to move, Ukrainian artillerymen had been pounding Russian positions with U.S.-made M270 multiple launch rocket systems.

Command posts. Ammunition depots. Fuel storage facilities. The firing was relentless. Across the front, Ukrainian military officials later said, Russian soldiers or their separatist proxies struggled to receive orders or coordinate with nearby forces as the rockets rained down. Some troops began to retreat.

“We broke through the front line, and the enemy started panicking,” Oleh said, speaking on the condition he be referred to by his first name because his relatives live in Russian-occupied territory. “They were panicking because we attacked all front-line positions at once — the entire front line itself was enormous — and everywhere there was a breakthrough.”

By the end of that first day, Oleh’s company had advanced about 11 miles with little resistance, reaching the edge of Volokhiv Yar, a picturesque town in a ravine. Capturing this key junction would allow Ukrainian forces to block two major highways heading into Izyum and Balakliya.

That morning, Evhenii Andrushenko woke up to four Russian tanks parked in front of his home in Volokhiv Yar. Soldiers were sitting in a gazebo alongside his fence, he said. “They were sitting there drinking beer,” Andrushenko said. “And talking about where to run.”

Oleh and his troops moved into the town. They had accomplished their first objective. And just as quickly they moved on, racing southeast for several days, with relatively little resistance, into spaces abandoned by Russian forces.

Under the original battle plan, the company, by Day 7, was to take up a position on a ridge north of Izyum, some 40 miles from the offensive’s starting point. But the day before, Oleh was summoned with other company commanders to a meeting. “Half the units in Izyum, maybe even the majority, are simply fleeing,” their battalion commander said. “So, we’re entering Izyum.”

Oleh’s company went first and dug in at the first Russian checkpoint in the city. Within minutes, a boxy Zhiguli sedan with flags and the painted letter “Z” — a symbol of the invaders — came speeding up the road filled with fighters.

If they were trying to flee, they were headed in the wrong direction.

“Come this way, my sweet,” Oleh said.

A soldier blasted the car with a rocket-propelled grenade.

“Enemy eliminated,” he said.

In the distance, the Ukrainian troops could see other Russian vehicles heading in the correct direction — out of the city.

“We expected that we would fulfill all the missions of the operation,” Syrsky said. “But that there would be this kind of cascading collapse — I didn’t expect that.”

When Oleh’s company entered central Izyum, having made it there without any losses, the troops were dumbfounded at what lay before them: Tanks in working order, ready to be driven. Abandoned artillery pieces, ready to be fired. Fuel tankers “filled up to the eyeballs.” Tons of ammunition and light weapons.

The Russian troops had had everything they needed for a serious defense, Oleh thought, except the will to fight and, apparently, enough men. Even the elite Russian units left in the area bolted, realizing Moscow had no backup cavalry to send.

“When we entered Izyum, some kind of feeling arose, like the taste of victory,” said the company’s 36-year-old chief sergeant, Anton Chornyi. “It seemed to everyone like the beginning of the end.”

Oleh fired up his Starlink satellite internet and placed a call. Some 75 miles east of where he stood, his parents were living under occupation in the city of Starobilsk in the Luhansk region.

“What on earth are you guys up to over there?” his father asked. Russian forces in Starobilsk had just fled, his father said, and separatist fighters were now manning the checkpoints.

Oleh told him they had taken Izyum and chased the Russians out of hundreds of square miles of territory in a matter of days.

“Well done! Well done!” his father said.

“Don’t worry,” Oleh said. “Soon we’ll be in Starobilsk.”

He wasn’t fully kidding. Oleh, it seemed, could soon be going home.

The rout in the Kharkiv region rocked Moscow.

Putin’s refusal for months to take the political risk of announcing a draft had had disastrous consequences.

Left with little choice, he declared what he called a “partial mobilization” to conscript up to 300,000 troops, his biggest and riskiest escalation since the start of the war. Hundreds of thousands of Russian men fled the country in a frenzy.

In a speech, Putin characterized the mobilization as a necessary step to fend off Western nations bent on destroying Russia. He also suggested he might use nuclear weapons.

“This is not a bluff,” Putin said.

Men board a train in Prudboi in Russia's southwest after President Vladimir Putin ordered a "partial mobilization" in the wake of Ukraine's victory in Kharkiv. (AP)

Putin sped up his annexation plans, declaring Ukraine’s Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson regions to be part of Russia despite lacking full control over them.

“I want the Kyiv authorities and their real masters in the West to hear me, so that they remember this,” Putin said in a speech. “People living in Luhansk and Donetsk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia are becoming our citizens. Forever.”

On Oct. 8, Putin also designated Gen. Sergei Surovikin the first sole commander to lead Russia’s war across the entire theater.

With a direct line to Surovikin, Putin began to receive a more unvarnished picture of the problems on the battlefield, according to two people familiar with the matter, who said that previously Putin had been given overly rosy assessments by his top defense officials.

The peril of his disconnect from reality could not be mistaken. Zelensky had arrived to stand in the center of Izyum.

After his company’s victory, Oleh’s soldiers spent about a week in Izyum in mid-September, relishing the thought that the war’s end was near. Then they headed southeast, crossing into the Donetsk region on orders to retake the city of Lyman.

Reality resurfaced along the way.

In a line of trees near the village of Korovii Yar, the company came under fire from three Russian tanks. Five men from Oleh’s company were killed, according to the chief sergeant. Twelve were wounded, including a squadron commander who led his soldiers for four hours after shrapnel ravaged his jaw. The Ukrainians ultimately took the village, Oleh said, but the racing advance had stalled to something tougher and slower.

Gains in the direction of Lyman would be hard-fought.

Oleh was 13 years old in 2014 when war came to his native Luhansk region. The Kremlin fueled a separatist conflict, forcing Kyiv to fight for the predominantly Russian-speaking territory in the east. But even in an area that historically had Russian sympathies, a young Oleh was always sure of his stance.

“I’m not a herd, and I don’t have a shepherd,” he said. “I was born and raised in an independent country. I have my own opinion, which in Ukraine has a right to live and exist. I don’t know how it is in Russia.”

After ninth grade, Oleh left for a local military school, then enrolled at the Odessa Military Academy in the department of airborne assault forces. Three and a half years into his four-year degree, war broke out. The students were sent straight to the front. Oleh ended up back in Ukraine’s east, first as a platoon commander and later as a company commander, leading soldiers who in many cases were years older than he was.

After Korovii Yar, the company moved farther south, taking up a position outside Lyman. The Russians in the city were nearly surrounded, but unlike their compatriots in Izyum, they fought.

“There was so much enemy artillery fire — everything they had, all the artillery they had, the tanks, everything, was unloading right onto us, onto us, onto us,” Oleh said. The only route out of Lyman for the Russians was a road with little cover. Finally, one night, the Ukrainian company heard the rumble of a large column of vehicles and covered the road with artillery fire.

Lyman, too, had fallen.

In the days since, Oleh’s company has advanced 17 miles east, just past the border of the Luhansk region, where Russia is deploying drafted conscripts by the truckload onto the front line 36 miles from his hometown.

“It’s still quite a long ways to my city,” Oleh said. “But every day we get closer and closer. I can’t wait.”

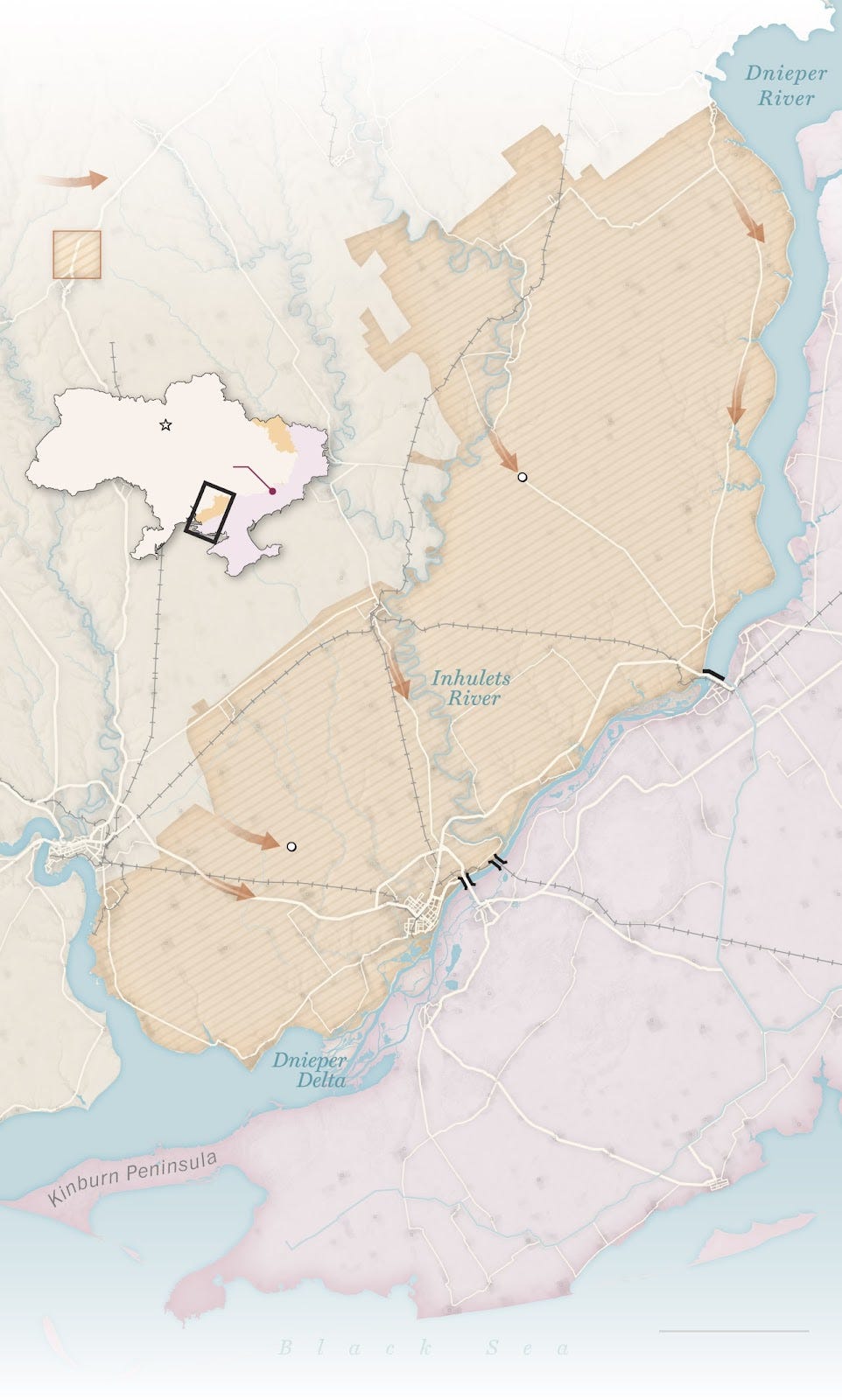

Kharkiv gave the Ukrainians a chance to push on an open door. Kherson presented a solid wall.

Over months of occupation, the Russians had dug trenches and built large defenses. The farmland of the steppe offered little natural cover for an attacking force, and a maze of irrigation canals as obstacles. Moscow had brought in its best troops.

“The minefields they set up there — they practically didn’t know themselves how many they set up. Everyone who came there would change them and add additional minefields,” said Maj. Gen. Andriy Kovalchuk, who was tasked with leading the Kherson counteroffensive. “We didn’t have the option to advance rapidly.”

To decide how to go about the operation, Ukrainian commanders arrived in Germany last July for a war-gaming session with their American and British counterparts.

At the time, the Ukrainians were considering a far broader counteroffensive across the entire southern front, including a drive to the coast in the Zaporizhzhia region that would sever Moscow’s coveted “land bridge” connecting mainland Russia with Crimea, which was illegally annexed in 2014.

In a room full of maps and spreadsheets, the Ukrainians ran their own “tabletop exercise,” describing the order of battle — what formations they would use, where the units would go and in what sequence — and the likely Russian response.

The American and British war-gamers ran their own simulations using the same inputs but different software and analysis. They couldn’t get the operation to work.

Given the numbers of Ukrainian troops and available stockpiles of ammunition, the planners concluded that the Ukrainians would exhaust their combat power before achieving the offensive’s objectives.

“This was them asking for our advice,” said a senior U.S. defense official, who like others in this article spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive military planning. “And our advice was, ‘Hey, guys, you’re going to bite off more than you can chew. This isn’t going to work out well.’”

Beyond the risk of running out of steam, a Zaporizhzhia offensive might have pushed Ukrainian forces into a pocket the Russians could surround with reinforcements sent along two axes, from Crimea and Russia.

“Our commanders thought the Ukrainians left pretty determined that they were going to do the whole thing anyway — just that there was a lot of pressure to do the whole thing,” the defense official said.

The White House reiterated the U.S. military’s analysis in talks with Zelensky’s office.

U.S. National security adviser Jacob Jeremiah “Jake” Sullivan talked to the Ukrainian president’s chief of staff, Andriy Yermak, about the plans for a broad southern counteroffensive, according to people familiar with the discussions.

The Ukrainians accepted the advice and undertook a narrower campaign focused on Kherson city, which sits on the west side of the Dnieper River, separated from Russian-held territory to the east.

“I give the Ukrainians a lot of credit,” the defense official said. “They allowed reality to move them toward a more limited set of objectives in Kherson. And they were nimble enough to exploit an opportunity in the north. That’s a lot.”

Kovalchuk set out to bisect the Russian-occupied area on the west side of the Dnieper and trap the Russian forces. “My task was not only to liberate the territory,” he said. “My task from the start was to occlude and destroy the force. That is, to not let them leave or exist.”

Failing that, the goal was to force them to flee. The 25,000 Russian troops in that portion of Kherson, separated by the broad river from their supplies, had been placed in a highly exposed position. If enough military pressure was applied, Moscow would have no choice but to retreat, Kovalchuk said.

Russia had to arm and feed its forces via three crossings: the Antonovsky Bridge, the Antonovsky railway bridge and the Nova Kakhovka dam, part of a hydroelectric facility with a road running on top of it.

The two bridges were targeted with U.S.-supplied M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems — or HIMARS launchers, which have a range of 50 miles — and were quickly rendered impassable.

“There were moments when we turned off their supply lines completely, and they still managed to build crossings,” Kovalchuk said. “They managed to replenish ammunition. … It was very difficult.”

Kovalchuk considered flooding the river. The Ukrainians, he said, even conducted a test strike with a HIMARS launcher on one of the floodgates at the Nova Kakhovka dam, making three holes in the metal to see if the Dnieper’s water could be raised enough to stymie Russian crossings but not flood nearby villages.

The test was a success, Kovalchuk said, but the step remained a last resort. He held off.

At the outset of the Kherson offensive, Ukrainian forces charged through Russia’s first-line defenses. Then they met fierce resistance.

A 32-year-old company commander named Yurii in Ukraine’s 35th Marine Brigade led his platoons in early September across a small river under fire, only to face a dug-in second line outside the village of Bruskynske, about 50 miles northeast of Kherson city. The Russians had been in the area for months, lining trenches with concrete and hiding tanks in deep ditches in the ground.

There, Yurii’s men felt the full force of Russian aviation. Russian military aircraft dropped high-explosive FAB bombs on his unit, which initially didn’t have any weaponry to defend itself or target the planes.

“This is a munition that leaves nothing behind,” Yurii said. “That explosion, that wave — when it’s 200 meters away, you feel it very strongly. It throws you back. … When we had direct hits on the positions with FABs, there was nothing left of the people.”

Ukrainian forces in the area were trying to push southward to bisect the Russian-occupied territory west of the Dnieper and get within artillery range of the Nova Kakhovka dam.

Ukrainian losses quickly mounted. With increasing numbers of armored vehicles destroyed or out of service, medics had to use pickup trucks to shuttle the wounded, often under fire from the Russians. Later, they used a Russian-made car.

“During the next evacuation, my combat medic was hit by shrapnel through the window directly into the car,” Yurii said. “During those two weeks, there was not a single window left in the car. Everything was smashed by shrapnel. But still the evacuations took place.”

By October, Ukraine had begun stabilizing the situation, and Yurii was dispatched to enter the nearby village of Davydiv Brid. There, he climbed a red metal structure, bursting with happiness, to record on camera that the village had been liberated.

A strong wind gusted. “We solemnly hang a blue-yellow flag above Davydiv Brid,” he yelled into the gale. “Glory to Ukraine!”

Back in Kyiv, impatience was growing.

Kovalchuk was insisting it was just a matter of time before the Russians retreated — the leaves were about to fall off the trees, the river would freeze in winter, the Russian forces were running low on supplies.

But for Kyiv, Kovalchuk wasn’t moving fast enough. He was replaced by Brig. Gen. Oleksandr Tarnavsky, a deputy of Syrsky’s during the Kharkiv operation.

A senior Ukrainian government official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss the matter publicly, said Kovalchuk “wasn’t getting the job done.”

But the change wasn’t publicly announced, the official said, so as not to provide Russia with any kind of propaganda victory. The Americans were informed.

“I think there were folks who were probably getting impatient with the movement in the south,” said a senior U.S. military official. “It was a really good start and then it just kind of stopped.”

Tarnavsky, the new commander, said he applied some of the principles he and Syrsky had used in Kharkiv, attacking where the Russians least expected it.

He said he singled out the territory between Mykolaiv and Kherson — flat farmland with few trees and obstructive concrete irrigation canals — as the place to mount the main offensive drive. “The calculation,” Tarnavsky said, “was the enemy wouldn’t think we would do it there.”

Responsibility for that difficult stretch of front, northwest of Kherson, fell to Col. Vadym Sukharevsky, commander of the 59th Motorized Infantry Brigade.

His men had charged through Russia’s front lines, overcoming losses, and were pushing against ferocious resistance to get close enough to strike the river crossings into Kherson with artillery. That fire would also make Russian resupply trips by pontoon barges nearly impossible. His forces were almost there. “It was literally a battle for every meter,” Sukharevsky said.

Up against elite Russian air-assault units, Sukharevsky’s less experienced troops were forced to engage in what he called battlefield “folk art.”

They modified the batteries in off-the-shelf DJI Mavic drones so the copters could fly four times farther, up to 13 miles. They obtained an additive used to give natural gas its scent and launched the foul odor into enemy trenches. They accepted drones from cigarette smugglers and transformed them into self-detonating explosives.

“Our army is used to fighting with improvised means,” Sukharevsky said.

One of his platoon commanders, Chief Sgt. Yevhen Ignatenko, the owner of a large Kherson grain-shipping business and a regional politician, explained how best to destroy his own barges, which Russia had requisitioned to ferry forces and supplies across the Dnieper.

Ignatenko drew on a lifetime of local knowledge — back roads, canals, pumping stations — to figure out how to advance through the difficult terrain. He also gathered information about the Russians’ activities from a network of sources behind enemy lines.

On the night of Nov. 9, Sukharevsky said, the brigade closed in on Zelenyi Hai, a village that put Kherson within artillery range. The Ukrainians began striking the river, he said. But the Russians had begun retreating days earlier.

Sukharevsky said he credits Ukraine’s victory partly to the artillery systems, guided munitions and long-range rocket launchers sent by the West, which eventually wore down a Russian force already low on ammunition and struggling with supply lines.

The pressure from Ukrainian troops forced the retreat, but they didn’t manage to run down or destroy the fleeing Russians. Mines, in some cases laid a meter apart and three rows deep or tucked into thin strips on the roads, prevented the Ukrainians from giving chase.

“They didn’t hold back,” Sukharevsky said. “They mined with everything, even new means we had never heard of.”

When Zelensky visited Izyum in mid-September, days after Ukraine’s Kharkiv offensive, the officials with him were tense, even though he was still some 12 miles from the front line. A visit to Kherson, with Russian snipers just across the river, posed a much greater risk.

Zelensky, however, could not be kept away.

Tarnavsky stood beside Zelensky on Kherson’s central square. “I was amazed at the people I saw,” Tarnavsky said. “All of their faces, there was just joy on them.”

Zelensky raised the flag over a liberated city for the second time in two months and described the moment as the “beginning of the end of the war.”

Ignatenko, the regional politician and Kherson shipping magnate serving in the 59th Brigade, sent a drone up over the river and found one of his barges half-submerged near the Antonovsky Bridge, but others were missing.

“We’ll find them,” Ignatenko said. “And if we don’t find them, we’ll build new ones. It’s okay. At least we will be a free country.”