The semi-contrition articles by Iraq War advocates is that they had meant to do a good deed but came up against "the limits of power" or something. I remember that period and do not recall being about doing something nice for some Arabs when I was in Islamic School.

Just 7 am in Indonesia, March 20th 2003, in the football mini stadium near my school (I’m still a student from JHS/Junior High School), when midnight, around 3 am, U.S. and west coalition (without Trio Germany, France, and Russia) landed in Basra and near Baghdad to toppling Saddam Hussein. I was in 8th grade at the time of the invasion, and will never forgive adults for being taken in by their lies, as I saw straight through it. The bombing of the Balkans (reported in Indonesia by Ade Novit, Atika Suri, Desi Anwar—now Desi is Editor in Chief CNN Indonesia, Dana Iswara, Zsa Zsa Yusharyahya) when I was in elementary school had a big impact on me.

Even after casualties near 1 million Iraqis since 2003 (compare: 4,475 U.S. service members who have been killed in Iraq since 2003, and 103,792 were diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)), Baghdad (STILL) the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. Not Riyadh, not extravaganza lavish Dubai, or even Tehran. Along the Tigris River, young Iraqi men and women in jeans and sneakers danced with joyous abandon on a recent evening to a local rapper as the sun set behind them. It’s a world away from the terror that followed the U.S. invasion 20 years ago.

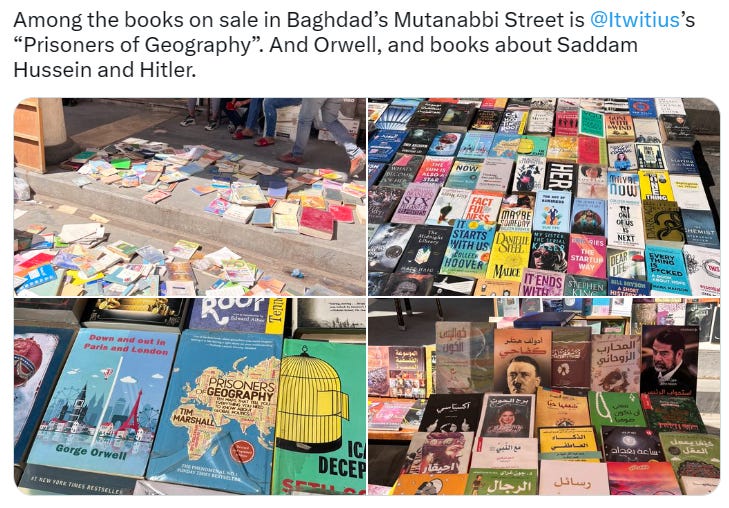

Iraq’s capital is full of life, its residents enjoying a rare peaceful interlude in a painful modern history. The city’s open-air book market is crammed with shoppers. Affluent young men cruise muscle cars. A few glitzy buildings sparkle where bombs once fell. Half of today’s population isn’t old enough to remember life under Saddam Hussein. In interviews from Baghdad to Fallujah, young Iraqis deplored the chaos that followed Saddam’s ouster, but many were hopeful about nascent freedoms and opportunities.

They (West Alliance, not including Germany and France) basically decided to make Iraqis pay for 9/11 even though they had nothing to do with it while some other elite psychopaths got an excuse to have the wars that they'd been wanting to have before the attacks anyways. They've never stopped lying til the present day. Somehow, despite that no one properly claimed this, through implication, 70% of adults came to believe that Saddam was linked to Al Qaeda and 9/11. This despite the fact that Saddam was a secular socialist who brutally stamped down on radical Islam.

We were further told that Saddam had "weapons of mass destruction" despite that they got him to agree to UN Weapons Inspectors who then found no weapons of mass destruction. But that wasn't good enough for people who were hell-bent on war. Invading Iraq meant different things to different people. For Rumsfeld/Cheney, it was about throwing the U.S. might around after 9/11. For Paul Wolfowitz, it was about “fixing”’ Bush 41’s (Bush Sr) mistake of leaving Saddam in power (Iraq invaded Kuwait on August 2nd, 1990 — then The Desert Storm Jan 19th, 1991 by West + Saudi + several Asia countries). Most of Iraqis problems were caused by sanctions, and the responsibility laid with the sanctioners. The public knew that. Machiavelli said you should not trust exiles, and despite Wolfowitz etc allegedly being Machiavellians they did not listen. For Bush, it was about preventing another 9/11 & being the savior.

The popular discourse has settled on the theory of the Bush administration as a well-oiled machine that sought to transform Iraq from a dictatorship to a democracy, one that would inspire other countries in the region to democratize as well (sort of a reverse Domino Theory). But this is a misperception. While Bush certainly bought into the idea—and referenced democracy in his speeches constantly—many of his subordinates didn’t really care if Iraq was a democracy or an autocracy. Rumsfeld was in this camp. Lots of motives drove this decision.

The late 65th U.S. Secretary of the State, Colin Luther Powell, said that backing the war in Iraq was a ‘blot’ on his record. David Jeffrey Frum (former speechwriter for President George W. Bush, 2001-2002, including Bush Jr statement after 911 as well, and coined the term “Axis of Evil.), never apologizing about nearly million Iraqis dead, with no blinking said one of his regrets about the Iraq War is that it shifted US public opinion against OTHER wars of choice. The late John McCain, before his dead, held himself responsible for his role in the “mistake” that was the Iraq War and accepted his “share of the blame.”

On the eve of the 20th anniversary of the invasion of Iraq, there was a cyclical irony to the whole story: the US was effectively admitting it had zero legal or moral authority to help prosecute Russian war crimes (by ICC —- then Putin replied with visiting, physically Crimea and Mariupol — tomorrow / March 20th back to Moscow to meet Chinese President Xi Jinping, maybe RUS-CHN commemorate the failure of West in Iraq, again, Putin-Scholz-Chirac refused to join 2003 invasion) in Ukraine because it had, itself, committed many of the same crimes, up to and including the invasion of another country. If ICC prosecute Putin, why not ICC prosecute Ehud Barak or Netanyahu about brutality Israel in Palestine, or Bush-Blair about Iraq 2003?

The Pentagon’s stonewalling attempts will likely be overturned, especially after lawmakers and officials are sufficiently reassured that “precedent” means basically nothing when it comes to international law and the ICC—which has, exclusively, out of its 41 public indictments, only charged Africans with war crimes in the 20+ years of its existence. There’s little reason to think this all-African run will change; however, given Russia’s relative pariah status on the global stage, its tiny GDP, and its flagrant disregard for civilian casualties, it’s possible they could make history and break the reverse color barrier. But the idea that the US, Israel, UK, and any other Western powers would ever be on trial for war crimes at the Hague has about as much chance of happening as a cracked egg spontaneously reassembling back into a full egg. Which is to say, it’s all part of the morality theater in DC, but not something anyone legitimately fears.

Indeed, not only have none of the hawks who promoted, cheerled, or authorized the criminal invasion of Iraq ever been held accountable, they’ve since thrived: they’ve found success in the media, the speaking circuit, government jobs, and cushy think tank gigs, and they currently occupy the Oval Office. Meanwhile, those in the mainstream who openly opposed the war—like, for example, Phil Donahue and Chris Hedges—were either fired or relegated to alternative media outlets. The almost uniform success of all the Iraq War cheerleaders provides the greatest lesson about what really helps one get ahead in public life: It’s not being right, doing the right thing, or challenging power, but going with prevailing winds and mocking anyone who dares to do the opposite. As far as the consequences of the invasion, ignoring that it was flagrantly illegal under laws the US usually purports to support, it was obvious even to an interested child what was going on and what would happen.

20 years on.

The first KIA of the Iraq war was an undocumented migrant who came to the US as an unaccompanied minor from Guatemala and joined the Marine Corps for citizenship.

He was killed by friendly fire two days into the invasion (March 22, 2003).

NSA's, CIA’s, & MI5’s role in Iraq was even more ghastly than the CIA's.

US forces killed thousands upon thousands of Iraqis based solely on oftentimes very flawed cryptographic analysis of their phones' metadata. Also true of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Yemen but Iraq was the worst)

Three main things you need to know for the 20th anniversary of the invasion of Iraq:

1) all the people who did it are still in charge

2) they're not even a little bit sorry for having killed a million innocent people

3) the second they get the chance, they'll do it again

"Arsenal" of chemical weapons in Iraq 99.99% is some old rusty old munitions given to Iraq by the Reagan admin in the 80s. Saddam swore he had no WMD and allowed UN inspectors in to prove it.

The CIA’s Iraq WMD conspiracy theory was thoroughly debunked PRIOR to the invasion of Iraq. The government and media class pretended to believe it anyway because they desperately wanted to have a big war that they could build careers off of. The men of Iraq had an inherent right, common to all people everywhere in the world, to defend their country from foreign occupation. Doing so did not make them terrorists, jihadists, Islamic militants, or any other category of “unperson.”

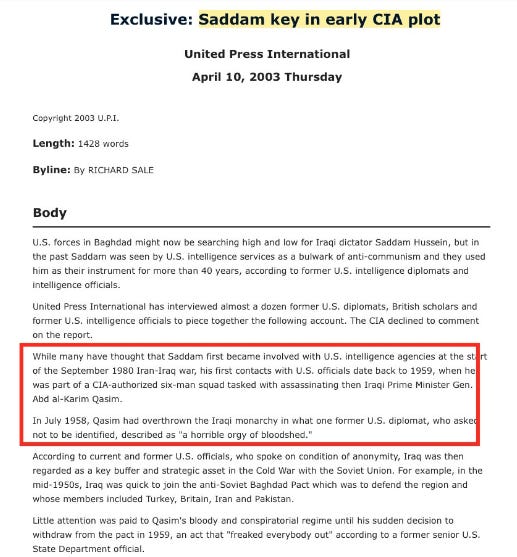

Even 20 years after the invasion of Iraq, people will still get really mad if you point out that young Saddam Hussein got his start in life as a contract killer for the CIA.

On March 12, 2006 (nearly 3 years after invasion), American soldiers stormed a house in the town of Mahmoudiya,south of Baghdad & raped 5 year old"Abeer Al-Janabi,"after killing her father,mother & sister (5 years old) &set them all on fire inside one of the rooms in the house. This crazy story is still the same gargantuan merciless as the My Lai massacre in Viet Nam by U.S. soldiers.

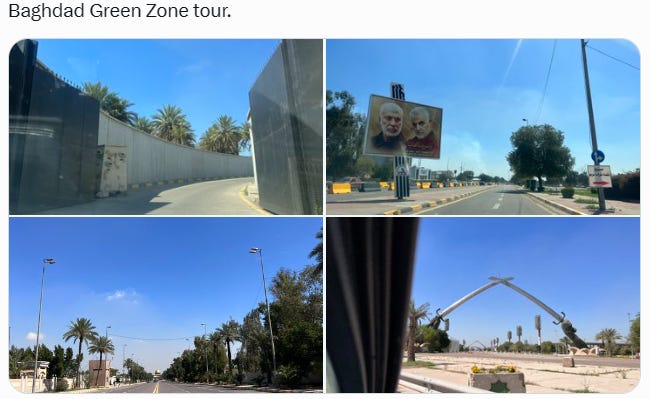

Midnight, March 20, 2003. US and the West alliance soldier heading across the river toward their targets into what the U.S. military would later call the Green Zone. The silence ended with the reverberation of Iraqi anti aircraft guns, their green and red tracer rounds flashing in the sky like shooting stars. A huge flash of light revealed where the first missile hit. Seconds later, the deep rumble of the explosion echoed across the city, its monstrous energy setting off every car alarm in the neighborhood.

Iraq fell into brutal civil war, and besides the destruction of the Christian community, the result was the empowerment of Shia's who then aligned with Iran instead of acting as a hedge against it.Really, the only thing that explains the decision to invade Iraq is the "Ledeen Doctrine", that "every decade or so we need to throw some insignificant country against a wall and show the world we mean business." [this was said about Ledeen, not by him]. In short, the US - UK policy class, with wide bipartisan approval, launched a brutal, murderous war based on lies, which destabilized an entire region and caused vast human suffering both at home and abroad while achieving no meaningful policy goals.

No goals besides wasting munitions which are replaced, and to enrich the military industrial complex, which probably was the purpose, and the Ledeen Doctrine was just a component. Last year, the US Defense budget reached $858 billion. I believe it was Pat Buchanan who once said [or perhaps he was quoting something] "Only an expert could believe such a thing, a normal person would never be so foolish", and this is indeed true of the alleged reasons for invading Iraq.

It's actually less bad for the public that they supported it, thinking it was over 9/11, than all the people who ostensibly understood international relations and strategic goals and still thought it would work.

Still, those blurry pictures were published the next day (or in Indonesia, in March 21 — 1 day after my exam football test in JHS, several newspapers show Iraq got bombed) on the front page of essentially every major Western newspaper, visually framing the public perception of those first days of the war.

Abu Ghraib prison. There in the darkest cells of Mr. Saddam Hussein’s terror apparatus, the sounds of men being tortured filled the hallways. The battered bodies of fellow prisoners were occasionally paraded past my cell in the foreigners’ wing of the complex.

Marked the start of a 20-year evolution of self-awareness, and my understanding to positioning myself as Pacifist - Pro Peace, of what the philosopher Judith Butler has called “the framing of the frame.” Dr. Butler wrote about the underlying systems of state power that define the frame of our narratives, that dictate what is kept in or out of it and that ultimately determine “which human lives count as human and as living, and which do not.”

Since the 1st week of March this year, competing narratives have made up an often incomprehensible web of “what was really going on.” The lines sometimes blur between victim, bystander and perpetrator.

In 2006, when Sunni Iraqis joined forces with the U.S. military to fight Al Qaeda, how quickly the Americans were able to redefine the narrative frame of the war. Insurgent leaders with blood on their hands became noble warriors in the “Sunni awakening.”

Almost three years after the discovery of remains of a missing relative killed during the sectarian violence that engulfed Baghdad, female relatives mourned during a funeral service in Najaf in 2010.

As an IR graduate, it needs to be critiqued and reflected on. The 20 years that have passed since I heard (on TV) after the Football exam about the US - plus The West Alliance (not with Germany and France). I no longer believe that it is possible to be an objective, uninvolved witness to war. I’d like to bring other IR students into a more honest and open conversation about the ambiguities of our study, our work, and how we might reframe and redefine the stories we tell about violence, conflict and human dignity.

Who has the power to narrate a conflict? Who determines the parameters of the frame? Which crimes or victims will be visible, and at the expense of what? I don’t provide any answers. But I argue that it is essential to keep asking the questions.

In a chandeliered reception room, President Abdul Latif Rashid, who assumed office in October 2022, spoke glowingly of Iraq’s prospects. Perception of Iraq as a war-torn country is frozen in time, he explains: Iraq is rich; peace has returned.

If young people are “a little bit patient, I think life will improve drastically in Iraq.”

Most Iraqis aren’t nearly as bullish. Conversations start with bitterness about how the U.S. left Iraq in tatters. But speaking to younger Iraqis, one senses a generation ready to turn a page.

Safaa Rashid, 26, is a writer who talks politics with friends at a coffee shop in Baghdad’s Karada district.

After the invasion, Iraq lay broken, violence reigning, he said. Today is different; he and like-minded peers freely talk about solutions. “I think the young people will try to fix this situation.”

Noor Alhuda Saad, 26, a Ph.D. candidate and political activist, says her generation has been leading protests decrying corruption, demanding services and seeking inclusive elections — and they won’t stop until they’ve built a better Iraq.

___

Blast walls have given way to billboards, restaurants, cafes, shopping centers. With 7 million inhabitants, Baghdad is the Middle East’s second-largest city; streets teem with commerce.

In northern and western Iraq, there are occasional clashes with remnants of the Islamic State group. It’s but one of Iraq’s lingering problems. Another is corruption; a 2022 audit found a network of former officials and businessmen stole $2.5 billion.

In 2019-20, young people protested against corruption and lack of services. After 600 were killed by government forces and militias, parliament agreed to election changes to allow more groups to share power.

The sun bakes down on Fallujah, the main city of the Anbar region — once a hotbed of activity for al-Qaida of Iraq and, later, the Islamic State group. Beneath the girders of the city’s bridge across the Euphrates, three 18-year-olds return home from school for lunch.

In 2004, this bridge was the site of a gruesome tableau. Four Americans from military contractor Blackwater were ambushed, their bodies dragged through the street and hung. For the 18-year-olds, it’s a story they’ve heard from families — irrelevant to their lives.

One wants to be a pilot, two aspire to be doctors. Their focus is on good grades.

Fallujah gleams with apartments, hospitals, amusement parks, a promenade. But officials were wary of letting Western reporters wander unescorted, a sign of lingering uncertainty.

“We lost a lot — whole families,” said Dr. Huthifa Alissawi, a mosque leader recalling the war years.

These days, he enjoys the security: “If it stays like now, it is perfect.”

___

Sadr City, a working-class suburb in eastern Baghdad, is home to more than 1.5 million people. On a pollution-choked avenue, two friends have side-by-side shops. Haider al-Saady, 28, fixes tires. Ali al-Mummadwi, 22, sells lumber.

They scoff when told of the Iraqi president’s promises that life will be better.

“It is all talk,” al-Saady said.

His companion agrees: “Saddam was a dictator, but the people were living better, peacefully.”

___

Khalifa OG raps about difficulties of life and satirizes authority, but isn’t blatantly political. A song he performed next to the Tigris mocks “sheikhs” wielding power in the new Iraq through wealth or connections.

Abdullah Rubaie, 24, could barely contain his excitement. “Peace for sure makes it easier” for parties like this, he said. His stepbrother Ahmed Rubaie, 30, agreed.

“We had a lot of pain ... it had to stop,” Ahmed Rubaie said. These young people say sectarian hatred is a thing of the past. They’re unafraid to make their voices heard.

Mohammed Zuad Khaman, 18, toils in his family’s café in a poor Baghdad neighborhood. He resents the militias’ hold on power as an obstacle to his sports career. Khaman’s a footballer, but says he can’t play in Baghdad’s amateur clubs — he has no “in” with militia-related gangs.

“If only I could get to London, I would have a different life.”

The new Iraq offers more promise for educated young Iraqis like Muammel Sharba, 38.

A lecturer at Middle Technical University in once violence-torn Baquba, Sharba left Iraq for Hungary to earn a Ph.D. on an Iraqi scholarship. He returned last year, planning to fulfil obligations to his university and then move back to Hungary.

Sharba became an biker in Hungary but never imagined he could pursue his passion at home. Now, he’s found a cycling community. He notices better technology and less bureaucracy, too.

So he plans to remain.

“I don’t think European countries were always as they are now,” he said. “I believe that we need to go through these steps, too.”

======

Shortly before George W Bush and Tony Blair launched their war, the Arab League issued a statement declaring that invading Iraq would “open the gates of hell”. Of all the pieces of intelligence that the CIA and British agents were gathering at the time, this turned out to be the only accurate one.

The invasion was launched on “evidence” about weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) that consisted mostly of whatever it was Iraqi informants knew our intelligence agencies most wanted to hear and would happily pay for. The biggest contributor to this self-fulfilling dossier was an alcohol-fixated defector called Curveball, who later admitted his improvisations about chemical weapons weren’t true.

No premise was too flimsy to get thrown on to the pile of spurious evidence. And before we knew it, that pile was big enough to justify sending our troops off into harm’s way. Many who made it home were broken for ever.

At the time, I was numb with confusion and horror that the entire West democratic system (exclude Germany and French) could allow an every leaders, fixated on a threat people were telling him wasn’t there, to get his party and his opponents to back a war with no purpose, no target, no endgame and no rationale. We all told Bush - Blair at the time it wasn’t going to end well. Now here we are, 20 years later, and only half right: it did go as badly as predicted, but it hasn’t really ended. The war’s hellish reverberations are still being heard: on top of the human suffering, the rise of militancy, the collapse of markets and economies, the mistrust of the west and the transformation of Tony Blair into a haunted husk. One of the biggest casualties has been truth, which the war swiftly dragged out into the desert and left for dead. Post Iraq 2003, we simply don’t trust what our leaders tell us.

I became less interested in the political personalities appearing on screens, and more interested in analysing what they were saying. I wanted to catch them using language to distort meaning, or to distract us from a larger but less appealing reality. Getting close-up to the dysfunction of power: was work in Indonesia parliament.

It feels real, an appeal to the heart, an offer of vulnerability, but that phrase “I only know what I believe” is a false friend: it sounds casual but actually subverts the tradition of empirical inquiry we’ve been successfully using since Aristotle. Normally, if we have a hunch, we test it. If we’re looking for an explanation, we eliminate every available solution or possibility until we find the right one. On a day-to-day basis, to survive, we first believe what we know.

any wonder the past few decades have been defined by a politics that appeals more to our emotions than to any evidence of our senses? More and more candidates are chosen, and more and more leaders are picked, on the basis of belief rather than ability. More and more debates are neutralised into take-it-or-leave-it mantras that aren’t open to question: craziness of Trump world since 2016 and saga about potential Trump got jailed on Tuesday March 21, Brexit , Putin vs Zelensky, stop the boats. This is a new emotional realm, “The people of this country have had enough of experts.”

Anyone who rails against this, who shows one iota of an appetite for facts and evidence, is lumped into catch-all categories of opponents: the metropolitan elite, the wokerati, the enemy within. This last one points menacingly at where we are now, 20 years later; in a land where criticism of the government in power is rebadged as treachery. Such are the booby traps that lie hidden in political discourse today; a landscape more littered than ever before with danger and lies.

The biggest lesson anyone would have taken from Saddam and the Invasion of Iraq is that the West polic(ies) class is untrustworthy and highly blunder, and you should never give an inch. This was, of course, confirmed by overthrowing Gaddafi 8 years later, after he made a deal. When 9/11 happened, though I was shocked by the event itself [who wouldn't be], I found it completely incredible that our entire society wondered "what did we ever do to anybody" despite us living in a country where bombing is routine policy. Accumulation from Serbia-Kosovo/Yugoslavia war (94-97), WTC 9/11, Iraq, Israel bombing in Gaza 2006, bring me to decide IR (International Relation) on 2007.

In the famous words of William Blum, "A terrorist is a man who has a bomb and doesn't have an airforce", which we are meant to believe is a vast moral difference, and the public lost their minds. 9/11 was not actually a good time in America that we should go back to.

=========

Bush Legacy

Leave it to George W. Bush to misspeak his way to the truth about the Iraq War that he launched 20 years ago. Last May, in a speech addressing Ukraine, he lambasted Vladimir Putin’s “wholly unjustified and brutal invasion of Iraq.”

Bush, stammering, quickly corrected himself but then conceded the point, murmuring, “And Iraq, too. Anyway…” His audience laughed awkwardly, allowing the former commander in chief, then 75, to deflect the significance of the moment with a senility joke.

It was indicative of how deeply the United States has avoided reckoning with the barbarism of invading, occupying, and privatizing Iraq, a reckoning that might have cast Putin’s war in an uncomfortably familiar light. Instead, Iraq demonstrates an innovation in American imperial amnesia: You don’t have to consider the lessons of a war if that war doesn’t end—let alone pay reparations for those you killed, tortured, and displaced.

There are all manner of differences between Ukraine and Iraq, but little difference in the imperial ambitions of their invaders. Both the US and Russia resorted to violence to bring a resource-rich country within their sphere of influence, and both underestimated the will and capacity of locals to resist. Whether phantom weapons of mass destruction or phantom Nazi regimes, the invading power resorted to paranoid pretexts to justify a war of aggression in unambiguous violation of the United Nations Charter. But where Bush claimed breaching the charter would strengthen the international order, Putin, unburdened by global hegemony and its necessary posture of lawfulness, didn’t bother with such ridiculous assertions.

Two other key differences concern Russia’s inability to take Kyiv and the support Ukraine enjoys from the NATO juggernaut. But both Putin and Bush found their militaries placed within a crucible while hawkish voices back in the metropole, seized with fears of humiliation, demanded escalation. Little wonder Bush found himself unable to remember which war he was discussing.

Bush’s escalation, the 2007–8 troop surge, never produced the promised political reconciliation among Iraqis. Instead, it entrenched Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, who persecuted the disempowered Iraqi Sunnis. But because it substantially reduced US troop deaths, the surge produced something subtler: a narrative that the Iraq War, after five agonizing years, had been functionally resolved—although to stay resolved, US troops, paradoxically, needed to remain in Iraq. It was a useful contradiction, forestalling not just an unambiguous defeat but the prospects for reconsidering what Barack Obama once called “the mindset that got us into war in the first place.” Now the only lessons of the war would be operational. And so Obama exported the surge to Afghanistan and pursued a new war in Libya, all while troops remained in Iraq.

In 2011, a fractious Iraqi parliament declined to extend legal protections to the remaining US forces, prompting Obama to recall the troops. Many in US national security circles decried the withdrawal as a failure of Obama’s diplomacy rather than as a verdict on the viability of a US presence from Iraqi leaders willing to work with Washington. When the Islamic State conquered Mosul in 2014, the blame in Washington went to the withdrawal, not the war that created ISIS’s parent entity, Al Qaeda in Iraq.

The horrors of ISIS preempted any discussion of how the original US aggression, compounded by the routine brutalities of occupation, generated enemies worse than its initial ones. US policy-makers considered the central error to be not the invasion but the departure. The efficacy of the Iraqi and Syrian Kurdish-led ground forces in dislodging ISIS reinforced a preference for proxy war—a perennial imperial strategy—over large-scale US combat. That preference is perhaps the dominant lesson of Iraq drawn by the US foreign policy establishment.

By 2021, President Joe Biden, who had been one of the most important Democratic validators of the invasion, had secured a residual force without a clearly defined mission. Roughly 2,500 US troops are deployed in Iraq, with 900 more in Syria. Ostensibly, they’re a backstop against an ISIS resurgence, but in practice, they’re targets for Iranian proxies. Biden, his Republican critics, and the security institutions all regard this as more responsible than ending an imperial misadventure. Doing so ensures they can persist in a delusion central to their hegemonic project: that the world is a grenade and America the pin.

The number of Iraqis who died because of our invasion may never be known. Conservative estimates put it in the hundreds of thousands, with millions more turned into refugees. The war worked out much better for Western oil companies. In 2008, as the surge was ending, the US State Department guided the Iraqi government in awarding no-bid concessions of the country’s oil wealth to ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, Chevron, and Total. “The Iraq war is largely about oil,” Alan Greenspan, former chair of the Federal Reserve, wrote in his memoir. He told The Washington Post that he advised Bush to invade because it was “essential” to securing the global supply. Meanwhile, this January, Iraq’s planning ministry said that 25 percent of the country now lives below the poverty line.

You’ll drive yourself crazy if you try to view US foreign policy through a lens of logical consistency rather than according to its signature mix of material interest and exceptionalist fantasy. The resemblance the Iraq War bears to the war in Ukraine does not create any obligation to leave that country to a Russian fate. Instead, recognizing it creates the context for reconsidering what America owes Iraq—and the world.

The United States owes the Iraqi people reparations for the destruction it inflicted upon them. It owes the world, as well as itself, a renunciation of its post–Cold War prerogative to police the globe. That would demonstrate that the US is interested in learning the fundamental lessons of its 20-year-old crime. Instead, it’s unable to summon even the self-awareness of George W. Bush, who mutters under his breath an embarrassed recognition that he is just like that which he most hates.