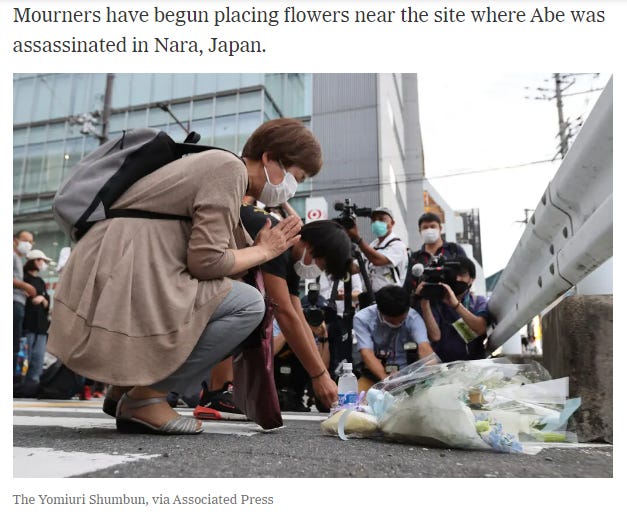

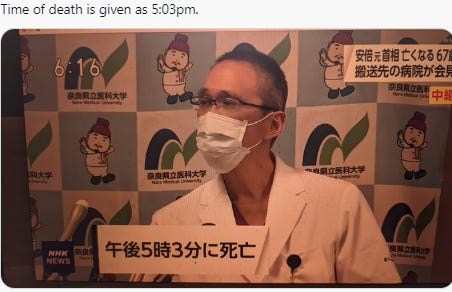

Rest in Peace, Abe Shinzo (5.03 pm Local Time).

Hours before Abe died in hospital near Nara prefecture, a lot of Chinese, with social media WEIBO, praised and celebrated for the shooter of Abe. This is to imagine how high tension is between Japan - China when Abe is in the seat (PM). Abe is the longest serving PM of Japan for the last 4 decades. Abe himself described it as “hawkish”. Just Day-5 after Russia-Ukraine war, Abe ask to Japan public to agree an idea about (Japan military have a) nuclear weapon to defending from everyone “enemies” (especially China). A country with (real victim of) Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the former PM himself put an idea about nuclear weapons.

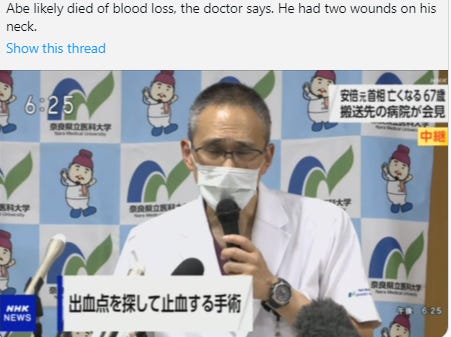

It’s Japan, a country with very strict regulations. Buy a weapon (very complicated-mandatory regulation) like you are buying a home. The shooting of former PM Abe Shinzo was especially shocking because of the extreme rarity of gun crime in the country, which has some of the most stringent laws around buying and owning a firearm. It’s really hard to convey how shocking this is in a country where gun violence is so rare.

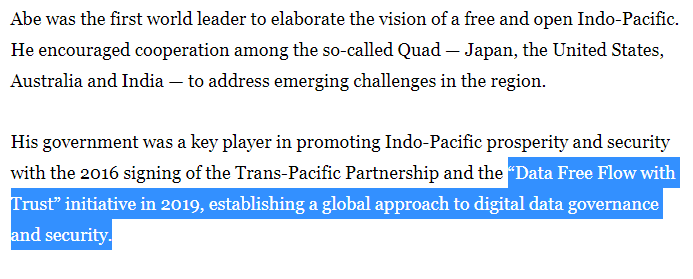

His successor, Yoshihide Suga and (now) Fumio Kishida, has come and gone. But institutional innovations that Abe spearheaded – namely, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or Quad – look likely to shape Asia’s geopolitical landscape for a long time to come.

Abe worked tirelessly to deliver the CPTPP, after Donald Trump effectively torpedoed its predecessor pact, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, by withdrawing the United States. The agreement that Abe revived currently includes 11 Asia-Pacific countries, with combined economic output of nearly $14 trillion.

Moreover, the CPTPP’s ranks are set to grow. The United Kingdom formally applied to join the pact last February. In September, China did the same, in an apparent effort to highlight its commitment to free trade – and set itself further apart from the US. Taiwan applied later.

Competition does harm some communities and individuals, but governments can target policies that encourage economic security, job training and adaptation.

Yet such countervailing policies are rarely taken, allowing frustration to mount among the groups that are losing out. Politicians like Abe then emerge to seize on that frustration, pursuing policies that are precisely the opposite of what is needed.” Prohibiting trade deficits invites retaliation, slows trade and eliminates competitive advantages that reduce costs for all.

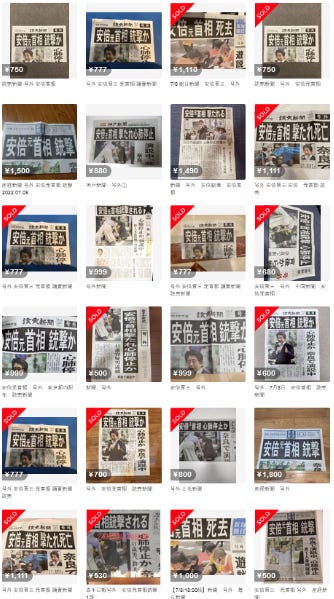

(newspaper across Japan after Abe dies)

On becoming Japan’s prime minister for the second me, Abe Shinzo has set himself the task of reviving Japan as a regional power, by repairing years of economic and political stagnation. However, his foreign-policy vis-à-vis China, are not yet clear.

Abe Shinzo’s premiership in 2006–2007 provides clues which suggest that he will seek rapprochement with China, while simultaneously developing strong regional es and fortifying the US-Japan alliance.

Abe’s foreign policy explicitly challenged the Yoshida Doctrine, despite his reputation as a conservative. Nothing that his flamboyant predecessor Junichiro Koizumi (another PM Japan with hawkish mindset —especially about China) had moved Japanese foreign policy away from the central tenets of the Yoshida Doctrine, Abe strove to distance the country from it even further in an effort to reshape Japan into a ‘normal power’: one with allies, national interests and hard as well as economic power. In order to achieve this, Abe sought to develop a more balanced relationship with Japan’s principal ally, the United States about balancing power in the Asia Pacific.

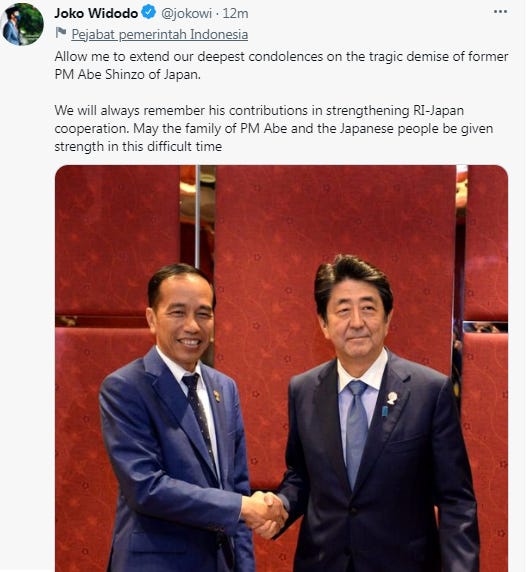

Under the Koizumi and Abe (both hawkish) administrations, the deterioration of the Japan-China relationship and growing tension between Japan and North Korea were often interpreted as being caused by the rise of nationalism. This thesis aims to explore this question by looking at Japan’s foreign policy in the region and uncovering how political actors manipulated the concept of nationalism in foreign policy discourse. The methodology employs discourse analysis on five case studies. It will be explored how the two administrations both used nationalism but in the pursuit of contrasting policies: an uncompromising stance to China and a conciliatory approach toward North Korea under the Koizumi administration, a hard-line attitude against North Korea and the rapprochement with China by Abe Shinzo, accompanied by a friendship-policy toward Indonesia.

These case studies show how the sentiment of nationalism is used in the competition between political leaders by articulating national identity in foreign policy.Whereas this often appears as a kind of assertiveness from outside China, in the domestic context leaders use nationalism to reconstruct Japan’s identity as a ‘peaceful nation’ through foreign policy by highlighting differences from ‘other’s or by achieving historic reconciliation.

Such identity constructions are used to legitimize policy choices that are in themselves used to marginalize other policy options and political actors. In this way, nationalism is utilized as a kind of political capital in a domestic power relationship, as can be seen by Abe’s use of foreign policy to set an agenda of ‘departure from the post war regime’.

In a similar way, Junichiro Koizumi’s unyielding stance against China was used to calm discontent among right-wing traditionalists who were opposed to his reconcilliatory approach to Pyongyang. On the other hand, Abe also utilized a hard-line policy to the DPRK to offset his rapprochement with China whilst he sought to prevent the improved relationship from becoming a source of political capital for his rivals. The major insights of this thesis is thus to explain how Japan’s foreign policy is shaped by the attempts of its political leaders to manipulate nationalism so as to articulate particular forms of national identity that enable them to achieve legitimacy for their policy agendas, boost domestic credentials and marginalize their political rivals.

Confronting difficult to reconcile role demands from the domestic and foreign audiences forced Abe to scale down his objectives to transform Japan's socio-political system and to make compromises. These compromises were related to historical issues, the organization of the state, the educational system, the centrality of the role of pacifism, and the reinforcement of Japan as a military power. Despite the commonality of viewpoints on many issues, a gap emerged over time during Abe's tenure as PM.

Abe Shinzo worked hard to present a non-confrontational viewpoint regarding China during the leadership contest.

For example, he (once) softened his language about China in his speeches, avoiding obvious an-Chinese rhetoric, while he also maintained a deliberate ambiguity over whether he would visit the Yasukuni Shrine should he succeed Koizumi as prime minister.

However, this policy had a political costs for Abe within his own party, as he was compelled to adopt an uncompromising position vis-à-vis North Korea in order to appease the right-wing factions of the LDP, which otherwise supported his revisionist policy regarding the Japanese constitution and his corresponding desire to turn Japan into a‘normal country’.

Fortunately for Abe Shinzo, his desire to revise the Japanese constitution, underpinned by conservative values, not only dampened criticism from the right, but also ultimately ensured strong support for his administration from this wing of the LDP.

(at Pearl Harbor, very rare visit)

In many ways, this was a balancing act in which right-leaning Diet members conceded Abe Shinzo’s China policy as a diplomatic achievement that would help win Abe the upper house election in 2007.

Furthermore, and perhaps somewhat paradoxically, the ease with which Abe was able to implement a policy of rapprochement with China was due to the fact that he was well known for his hawkish, an-Chinese views. As a result of this, right-leaning LDP factions were willing to give him the political space he needed to pursue his policies on China that they would not have afforded his rivals.

This was reminiscent of “Ping-Pong Diplomacy”, Richard Nixon’s freedom to pursue a rapprochement with China in the 1970s, which largely rested on his support within the right-wing bloc of the Republican Party and hard-line views on communism.

Likewise, Abe’s political agenda of the ‘departure from the postwar regime’ had also an oppositional framework in it. As discussed in later chapters, Abe’s targets were those who had created and supported the ‘postwar regime’. According to Abe, they were ‘bad’ because they should be responsible for postwar Japan’s disgrace through actions such as ‘apology diplomacy’ in Asia, the endorsement of the ‘imposed Constitution’, and the rise of values of materialism without national pride among the public.

In terms of factional politics, they were mainstream politicians in the LDP: the Kochi-kai and the Keisei-kai although it was not clearly named. In particular, the Keisei-kai was implicitly constructed as a kind of ‘fifth column’ because of its ‘friendship-first’ policy toward China.

But like today, immediately after news reportage Abe Shinzo got a shot in Nara, immediately celebrated. This is a really huge moral hazard between Japan (PM Fumio Kishida, and Foreign Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi) and China (President Xi Jinping, and FM Wang Yi) to repair. Both Foreign Ministers are now at the G20 FM meeting in Bali. And Abe Shizo’s brother, Nobuo Kishi, is the current Japan Defense Minister. I’m really worried some hawkish Japanese want retaliation after Abe died.

Once again, Rest in Peace Abe Shinzo.