Bears repeatedly - endlessly - we are living in an age of brazen tyranny. No longer is the West concerned about negative optics of draconian, undemocratic, illiberal actions. They make zero effort to conceal this stuff. And they're unconcerned about consequences. God help us all.

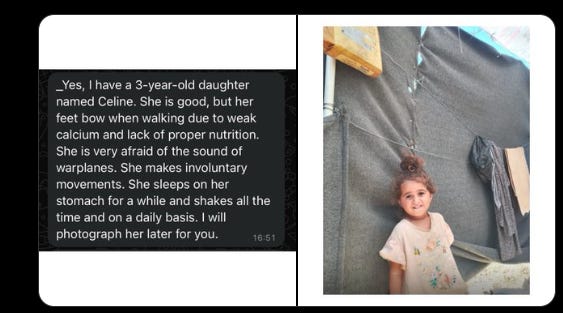

Tasneem ist 24, sie stammt aus Jabalia und studiert Kommunikationswissenschaft an der University of Palestine im Süden von Gaza-Stadt. Oder besser: Sie studierte. Denn ihre Uni wurde – wie alle anderen Universitäten in Gaza – von der israelischen Armee zerstört. Tasneem hat eine dreijährige Tochter, Celine. Ihre Wohnung mussten sie verlassen, heute lebt ihre Familie in einem Zelt westlich von Khan Younes. Über ihre Tochter Celine sagt Tasneem: „Ihre Füße geben beim Laufen nach, weil sie zu wenig Kalzium hat, weil sie sich nicht richtig ernährt. Sie hat große Angst vor dem Geräusch von Kriegsflugzeugen. Sie zittert die meiste Zeit.“ Tasneems Tante.

It’s not shocking that Western publics would be eager to avert their eyes from the immense suffering that was Hamas’s terror attack on October 7, 2023. It is not shocking the same publics would want to look away from the unremitting horror the Israeli military is unleashing in Gaza. How different countries manage to avert their eyes is a story at once consequential and nugatory. The stakes of this evasion seem massive—the violence of Hamas’s attack, the agony of civilians in Gaza—but ultimately the subjects are small. And perhaps nowhere has the process been so retrograde, cruel, and unthinking, so small and petty, as in Germany.

For this is perhaps the most curious thing about German public discourse after October 7: nothing has changed. Late 2023 and early 2024 have been characterized by endless culture-war freak-outs, which, as media creations, move at dizzying speed, yet seem to go on forever. In the months since the massacre, every major newspaper and magazine has published almost weekly variations of the same texts: an excoriation of “woke,” “postcolonial,” “intersectional,” “international leftists” and their “identity politics,” now exposed for the closet antisemites they have been all along.

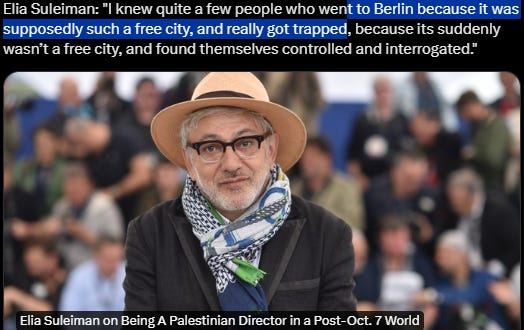

When Israeli director Yuval Avraham declared his solidarity with Palestinians and used the word “apartheid” in an acceptance speech at the Berlin Film Festival in February, the news cycle about the event dragged on for two weeks. (A cabinet minister who was in the audience later clarified that she had only clapped for a part of Avraham’s statement.) When Greta Thunberg spoke out in support of Palestine at a protest in Amsterdam, German media debated “the idol off-track” (Irrweg eines Idols) for the better part of a month—including a five-thousand-word cover story in Der Spiegel, published in both German and English, in case readers elsewhere wanted to hear German media’s thoughts on whether Thunberg “is antisemitic or just incredibly naïve.”

In May, when a solidarity encampment modeled on those at Columbia and CUNY sprang up at the Free University in Berlin, police in riot gear swooped in to clear it within three hours, even swifter than their US counterparts. The ensuing news cycle about the serious threat posed by these young people and the “Hamas takeover” of US universities kept Germany’s chattering classes busy for weeks. As the month drew to a close, several posts that the president of the Technical University of Berlin had liked on X led to a clamor for her resignation (including from her ostensible boss, the mayor of Berlin). One of the offending posts was about a protest in solidarity with Palestinians in Istanbul, accompanied by an image apparently featuring—if you zoom in closer than my phone was able to—a picture of Benjamin Netanyahu marked with a swastika.

The endless state of agitation is not lost on those agitated. But they have a very particular view of their own agitation. “Undoubtedly there is much that is neurotic” about postwar Germany’s feeble attempts to grapple with the Nazi years, Theodor Adorno suggested in a famous 1959 lecture on “The Meaning of ‘Working Through the Past.’” Adorno’s text has come up a lot in recent months, as have feelings of “German guilt,” which Adorno acutely summarized as: “defensive postures where one is not attacked, intense affects where they are hardly warranted, an absence of affect in the face of the gravest matters.”

But Adorno’s real point was that the focus on guilt was misplaced. Today, too, fixating on guilt and its compulsive, repetitive rituals in modern German politics misses something essential: German glee. These news cycles drag on forever because someone somewhere enjoys them, because it allows them to say and do what they’ve long wanted to say and do. For all the apocalyptic rhetoric, this has been a moment of liberation rather than repression for many German writers and politicians.

“Germans” pointedly does not mean all people in Germany. Many dissident voices have expressed themselves in journalism, essays, protests, open letters. A survey in March 2024 found that 70 percent of those polled were critical of Israel’s actions in Gaza; another from April found that 57 percent wanted their government to criticize Israel more explicitly. This says nothing about feelings about antisemitism or movements like BDS, of course; but it does suggest that politicians and journalists are having one kind of conversation, while people outside those fields are having another, or likely many other conversations. The story, then, is not about Germany, but a certain segment of society, about the reactionary radicalization within a bubble of political and cultural elites: disproportionately white, disproportionately identified with existing institutions, and disproportionately—let’s face it—neither Jewish nor Palestinian. It is among such people that we can see a defiant reprovincialization of the German spirit: a pride in not understanding or participating in analogous debates that rage elsewhere, a perverse pride in imposing one’s own categories, as though historical guilt confers true expertise.

Many of the turns in German public discourse will be familiar to consumers of US media: campus panics and selective police reporting that plucked young people and their opinions from obscurity to score huge political points; bad-faith screeds that tried to make any one stupid or inarticulate statement online stand in for a broader malaise of—take your pick—“wokeness” or “the Left”; meta-conversations that seemed designed to evade the imperative question of how Israel’s Western allies should respond to the Gaza War. But while the US public has seen these patterns wax and wane as the war has dragged on, with certain narratives ascendant and different groups gaining or losing definitional power over the conflict, the elite German reaction largely repeats a tired set of habituated legerdemains. Germany doesn’t give the appearance of working through anything; it hardly appears to be working at all.

Almost immediately after the October 7 massacre, Germany began a bizarre reckoning, deeply serious in self-conception, absolutely farcical in execution. Any silence, any hesitation, any nuance, any failure to use specific language—all this was called out with immense glee. At times literally: the conservative daily Die Welt contacted various activists, celebrities, and others for comment on the massacre. If they didn’t respond, or didn’t respond in the way Die Welt thought appropriate, they were accused of colluding with terrorists. Sascha Lobo in Der Spiegel was quick to discern “an almost monstrous silence” on “the Left” that ultimately amounted to a “hidden legitimation of mass murder.” Who exactly, specifically, was guilty? “Usually loud voices from the left, many intellectuals, authors, artists, part-time philanthropic influencers and activists.” Instead of specificity, texts like Lobo’s make a tacit admission: it wasn’t silence that was at issue; it was silence from people previously perceived as too loud. Failure to tweet or post about October 7, especially if one had the temerity to post about other social-justice causes in the past (and especially if that cause was Black Lives Matter), immediately became world history’s verdict on—again, take your pick—postcolonialism, wokeness, identity politics, the left, postmodernism.

“We often have too much outrage in our debate culture,” Vice Chancellor Robert Habeck remarked in a speech on November 1. “But here we can’t be outraged enough.” Habeck voiced the principle that seems to have guided much German public discourse since October 7: the only adequate response is excess. Text after text conjured caricatures of pampered, unfeeling left-wing “Hamas-lovers.” “From Coldbrew to Caliphate,” went one magazine headline: “The hipster has lost his innocence.” The cultural signifiers were often highly specific—blue hair, genderqueer, lattes—yet it was often unclear whether they sprang from a writer’s imagination, or, perhaps more likely, derived from exactly one person the writer happened to know. The Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung ran a column about “feminists or intersectional activists who just declared misgendering to be an act of violence,” who now “take to Instagram to declare Hamas’ crimes to be acts of resistance, revolution and decolonization.” The mention of Instagram strongly suggests where the columnist’s research began and ended.

The many withdrawn invitations, canceled events, personal vendettas—one German-Israeli author, a vocal critic of the war in Gaza, found himself the subject of a multi-page profile in Der Spiegel mystified by his “radicalization”—have diminished and coarsened German public discourse. But the deeper problem with Germany’s outrage is its entwining of moralism and abject moral failure. It has somehow yet to register that, in the face of horrific suffering in Israel on October 7 and the unimaginable destruction in Gaza since then, in the face of the tens of thousands of civilians slaughtered and hundreds of hostages still unaccounted for, it is more than a little strange to direct your rage at Instagram stories you swiped through on your bathroom break.

This overheated reaction was at once deprovincializing and provincializing. Much of the German debate occurred in reaction to US and British discourses, but it oscillated between completely identifying these (quite different) developments with Germany, and marking them as utterly alien, insensate to Germany’s unique world-historic position and responsibility. Foreign discourses often retained their threatening foreignness—the Judith Butlers of the world were spreading their insidious poison of gender theory mixed with postcolonialism and thereby reintroducing antisemitism to Germany—even as at they were covertly domesticated. Germans were freaking out about college campuses, celebrities, and activists, and you had to look twice to notice they were almost all American. Events at Berkeley became the backdrop for canceled events in Hamburg, Cologne, Berlin.

Amid all the panic, the discourse’s nominal subjects had a funny way of disappearing. In articles, in political speeches, in social media feeds, one again and again faces the fact that German discussions of antisemitism seem barely to require Jews. There are plenty of Jews and Palestinians living in Germany; the latter have been notably sidelined, the former (rhetorically) centered. Yet both Germany’s Jews and its Palestinians are strangely faint in these debates. Jewish voices, it turns out, are heard in Germany only when they say very specific things. In a TV debate with Robert Habeck, the writer Deborah Feldman said she was “appalled at how Jews [in Germany] can in principle only be considered Jews if they support the Israeli government’s right-wing conservative policies. . . . You are selective in protecting Jewish life.” Habeck’s response: he had spoken “with Jews” who saw things differently. “‘Valuing diversity means the ability to be different without fear,’ Adorno said,” wrote Volker Beck, an influential member of the co-governing Green Party, on Twitter in November. Here was an important, historic Jewish voice enlisted to make a point about protecting diversity. The problem was that Adorno never said this. Rather, in Minima Moralia he argued that a “just society” would need to transcend “abstract equality” (die abstrakte Gleichheit der Menschen) if people were ever to be able to be different “without fear.” A point as challenging and complicated today as in 1947—but in today’s Germany it can only appear as an easily digestible Instagram bromide.

Along similar lines, German newspapers and public figures began referring to October 7 as a Zivilisationsbruch—a rupture in civilization. The Jewish German historian Dan Diner coined the term to describe “a shattering of ontological certainty” in the Holocaust. Something formerly unthinkable had become real, and thought and memory had to adjust accordingly. Once the term entered the discursive churn last fall, the “rupture” widened to encompass ever more phenomena: international or German reactions (or even the lack of reaction) to October 7. An article by Beatrice Frasl in the Wiener Zeitung used the vocabulary to describe people who, “with oat milk lattes in one hand and your smartphone in the other, left the framework of civilized life . . . with your pastel-colored Insta slides and your stupid slogans.” “We won’t forget any of this,” she intoned. “Never forget,” Zilvilisationsbruch: such articles were happy to deploy a vocabulary schooled on decades of serious reflections on the Holocaust against oat milk lattes.

At least some of German-language media’s myopic reaction to the massacre must also be understood in light of the case of Fabian Wolff, which obsessed the German culture pages in the months immediately before October 7. Wolff is a journalist who for years wrote for various German newspapers—including the Jüdische Allgemeine, Germany’s most-read Jewish weekly—and is best known for a 2021 essay about his conflicted feelings about Israel and the BDS movement, written from his perspective as a German Jew. Last summer he revealed in another essay that he had learned that he was, in fact, not Jewish. Reactions ranged from the understandable—his former editors at the Jüdische Allgemeine felt betrayed—to the unhinged. Many voiced their suspicion that there was in Germany such a burning desire for Jews critical of Israel that when none could be found, one had to be made up: “The ones who should really take pause,” wrote Felix Dachsel in Der Spiegel, “are those Germans who eagerly court any star witness, be he ever so shaky, so long as he takes aim in some way at Israel.” In the conservative daily Die Welt, Dirk Schümer snarked that “in an age where people are granted the right to freely choose their gender, why should they not also claim Jewishness by fiat?” The diagnosis seems odd in hindsight: as the last half year has shown, instinctive solidarity with Israel runs deep. And the snide reference to trans people makes it seem as though this isn’t about Jewishness at all. More importantly, though, the German media elite drew an additional lesson from the affair: Jewishness that voiced criticisms of Israel could only be a performance, a put-on. Jews who didn’t conform to the established images and positions that Germans had assigned them were perhaps not Jews at all.

As protest encampments spread across US campuses in April 2024, several German publications contacted me for interviews, some of which were even published. I was repeatedly asked how afraid “my Jewish students” were. “Which ones?” I would usually respond. “The ones highly critical of the encampments, or those in them?” My interviewers often seemed to take this as trolling. They never adjusted their questions, never followed up on my answer, as though the many Jewish students in the encampments were a mirage, a hoax, a trap. Meanwhile, in a Pew poll from February 2024, fully one-third of US Jews said they found Israel’s actions in Gaza “unacceptable.”

German intellectuals seem imperiously certain about what is happening elsewhere in the world and how to interpret it, while showing ever less interest in what people elsewhere are actually saying. In the 1950s and ’60s, Adorno worried that postwar German society was not serious about “working through the past,” that the very phrase in fact hid a desire to be done with that past, to move on. Laudably, the postwar generation he taught set out to prove him wrong. But along the way, Germany became oddly, proudly possessive of the process of confronting its past, a world champion at explaining what “never again” entailed, and policing what it didn’t. In his epic, unperformable play The Last Days of Mankind (1918), Karl Kraus criticized the idea of Germany as the “land of poets and thinkers” (der Dichter und Denker): “German Bildung has no content, but is rather home decoration with which the land of judges and executioners (der Richter und Henker) seeks to ornament its emptiness.” Adorno, Hannah Arendt, and even, one worries, their living Jewish fellow citizens have been turned by today’s German elite into decorations, coefficients of German comfort and security. The idea that October 7 occasioned a “moral reckoning” is everywhere. Article after wrenching article appears, full of apocalyptic indictments, insisting that “everything needs to be different now.” Yet language has perceptibly ossified, calloused into ritualized invocations, incurious and morally inert—or better, reduced to a defensive crouch.

State elections were held in Bavaria and Hesse on October 8, 2023. In both states, voters lurched sharply to the right, after electoral campaigns fought over migration and culture-war imbecilities. The far-right AfD won 18 percent of the vote in Hesse and 15 percent of the vote in Bavaria. If anything, the latter number understates the rightward turn: both the conservative Freie Wähler (FW) and Bavaria’s eternal governing party, the CSU, effectively ran on AfD-lite platforms.

The FW are led by Hubert Aiwanger, lieutenant governor of Bavaria, who in summer 2023 was briefly at the center of a strange controversy: Aiwanger or someone close to him had made an antisemitic flier while in high school. Aiwanger claimed it was a “dirty campaign” against him, insisting that his brother had made the flier. Voters seemed happy to take him at his word, and after an initial dust-up, the media moved on. Amnesia about one kind of antisemitism since October 7 is complemented by hyper-memoriousness about anything a student protestor, a climate activist, or a gender theorist might have said.

As the left parties have either imploded (Chancellor Scholz’s SPD) or fragmented (Die Linke) in recent elections, it was hard not to scan the election-night graphs and notice that if combined, the black bar (representing the CDU) and the blue one (representing the AfD) would form a comfortable majority. The CDU itself has certainly noticed: under its new party chairman, Friedrich Merz, the CDU has tacked hard to the right, forswearing Angela Merkel and all she represented, and campaigning largely on immigration and anti-“woke” culture wars, issues previously owned by the AfD. The unsurprising result was minimal gains for the CDU and massive ones for the AfD. But the CDU is not alone: whether the liberal FDP, Scholz’s SPD, or even the Greens, almost all parties are following suit on immigration, contemplating deportations, asylum restrictions, and less money for refugees.

German politics regularly lurches rightward; this time, however, it is becoming clear—based on coalition math, but also ideological alignment—how a far-right party would not just enter German parliaments, but state cabinets, governors’ mansions, perhaps even the Berlin chancellery. The state of Saxony will vote for its state parliament in September. In the European Parliament elections in June, the CDU won 21.8 percent of the votes, the Social Democrats 6.9 percent, the Greens 5.9 percent, Die Linke 4.9 percent, and BSW, a new diagonalist party run by former Die Linke politician Sahra Wagenknecht, gained 12.6 percent. The AfD outran them all, with 31.8 percent of the vote. The numbers in other eastern Länder were similar. If the CDU were willing, then, the AfD could hold the governor’s mansion and a sizeable parliamentary majority in a matter of months. With that comes not only legislative power, but control of the many cultural institutions that depend almost entirely on government funding, an education sector overseen by the state department of education, thousands of civil society projects, foundations, and more.

All this has cast a shadow over German politicians’ reactions to October 7. Outrage at Hamas’s attack quickly entered into an unholy alliance with electoral math, inevitably leading back to yet another discussion of the woes of immigration. Within a week of both the massacre and the election, Chancellor Scholz appeared on the cover of Der Spiegel declaring that “finally” Germany must “deport people at massive rates”—to combat antisemitism, of course. Climate action fell victim to what were regarded as Greta Thunberg’s failings. And when the German political class closed ranks in support of Israel, the results looked more like white German identity politics than anything else. On X, one member of the Bundestag for the liberal FDP posted her own recipe against antisemitism: “asking immigrants to recognize our values and culture,” “to celebrate the Feast of St. Martin, Christmas or Easter.” (Nothing says “making space for Jews” like promoting Easter and Christmas as part of your “cultural values.”) Another suggested that in the wake of the massacre, “a clearer distinction” was needed “between basic rights for Germans and basic rights for all the others.” The vice chair of the same party proposed restricting where non-native Germans could live within Germany.

These are the characteristic language games of the German right: and now politicians across the spectrum make these seemingly baffling connections, and a much larger swath of voters and journalists than before seem to accept them as logical and plausible. When white, non-Jewish Germans try to imagine the fear felt by their Jewish neighbors and friends, they instead paint a vivid picture of their own; that they themselves might figure in their Jewish compatriots’ fears is not a possibility they find worth contemplating. When neighboring countries like France and Belgium react differently to the ICC arrest warrant for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, a CDU politician will take to X to explain their motives as mere “fear of riots on the parts of Islamists.” Campus protests? Funded by Hamas sympathizers in Qatar. Violence against Israelis is redeployed to fantasize about exclusion of those—immigrants, Arabs, Muslims—whom one has always wanted to exclude. All the talk of solidarity and empathy for “Jewish life” has revealed itself as a discourse about and for white, non-Jewish Germans—their grievances and fears, and their comfort.

And it has played out largely on the far right’s discursive home turf: culture war freakouts, xenophobia, vilification of Germans with “foreign” roots, and endless screeds about moral rot on “the left.” Between the elections in Bavaria and Hesse and the European elections on June 9, Germany saw some of the largest mass protests in its history—against the right, against the AfD—only for the same politicians who proudly marched on Sunday to return to the office on Monday and try to curb immigration and censor students. The same voices that constantly abetted an ugly, provincial master mentality were surprised that the appeals to tolerance and pluralism they also made occasionally did not have the intended effect.

Meanwhile, you get the sense that media and cultural institutions are also testing the waters. Imagine you are a journalist, or the head of some public institution, under a future “black-blue” (CDU-AfD) coalition. How would you continue doing your job? The provisional answer from some quarters has been to tacitly play along with their culture wars: restrict speech everyone agrees is objectionable anyway; frame white majoritarian identity politics as moderation and historic responsibility. Just as the war in Gaza has turned many German politicians into stodgy institutionalists cosplaying as populist firebrands, it is turning much of the German media into reactionary centrists.

“There is a term that precisely describes the incomprehensible,” expounded an article in Die Zeit from October 2023: “radical evil. It comes from Immanuel Kant, a philosopher who was ostracized by postcolonial thinkers as the chief ideologist of Western morality because of a few racist comments and excluded from the range of valid intellectual references.” The passage moves seamlessly from decrying postcolonial antisemitism to claiming, as a new victim of that antisemitism, Immanuel Kant—noted non-Jew and, dare I say, a bit of an antisemite. When a show at the Saarland Museum by the artist Candice Breitz was cancelled in November, one alleged instance of her antisemitism (Breitz is Jewish) was that she “had connected the current political situation in Germany to ‘authoritarianism.’” More often than not, the ultimate “victim” of the offenses denounced in the German press is no actual Jewish person, but only the German state.

In fact, it is a time for score-settling against a whole range of recent social justice causes. Critics like Beatrice Frasl in the Wiener Zeitung imagine their antagonists as hypocrites “who tweet . . . about #MeToo but can’t really think of anything to say when Jewish women are mass raped because they are Jewish.” The comparisons are meant less to appeal to socially conscious Germans than to belatedly delegitimate the defining protest movements of the past decade. One article syndicated in a series of Swiss newspapers declared that the “silence” of “feminists” about the rape of Israeli women had exposed “the MeToo movement for what it really is: a lying, unethical group that decides on a case-by-case basis whether the rape of a woman is an atrocity or . . . an action that should be cheered on.” The author, Roger Schawinski, is a man, but it hardly matters; the number of women writing nearly identical pieces is staggering. If published just a year earlier, they would have been anti-wokeness screeds; now they rehearse a new consensus on antisemitism.

These texts fetishize Jewish suffering and fear, yet react with furious recrimination against any attempt to represent Palestinian suffering—let alone to talk about both. Frasl gives two anecdotes as the sum total of evidence for the failure of the “international Left” to come to terms with Hamas’s cruelty: one concerns “US professors” calling the massacre “exhilarating” (exactly one US professor seems to have used this word); the other is an erroneous headline from the New York Times about the bombing of the Al-Ahli Arab Hospital, which was later corrected. “You remember the hospital supposedly bombed by Israel that was never actually bombed?” Frasl snarked. “That was never actually bombed.” The victims of the Al-Ahli Arab Hospital attack simply do not exist. Judith Butler often charges that the Palestinian dead are essentially ungrievable in the United States. This is of a different order altogether: a refusal to even say they’re dead.

Across the political spectrum, a central segment of the German media and political classes tell themselves that antisemitism and its supposed stalking horses (postcolonialism and intersectionality) have been imported to the country by globalist elites, rootless cosmopolitans who give ideological aid and comfort to the “wrong kinds” of immigrants. These narratives seem to draw on more than a few motifs we associate with antisemitism; but more remarkable instead is the hypersensitivity to antisemitism in Instagram tiles and gender theory, and the simultaneous unconsciousness of the same elements elsewhere. In this story, crooked “international” (that is, US) interests have perverted German purity, corrupted it with corrosive ideas—of antisemitism.

In the days after October 7, President Frank-Walter Steinmeier and Vice-Chancellor Robert Habeck both gave big speeches that were widely circulated. Habeck’s ten-minute video message first addressed Germany’s unique responsibility for Israel’s security. He then described the fears of German Jews who keep their children out of schools, decide not to wear a Star of David, and “do not dare go into certain areas—here, in Germany, almost eighty years after the Holocaust.” (This certainly describes the reality of some Jews in Germany, but for Habeck it appeared to be all of them.) Muslims, he went on, “have to be loud and clear in denouncing antisemitism, lest they risk their own claim to tolerance.” Habeck didn’t say “our tolerance”—grammatically he didn’t have to—but it was clear whose tolerance was to be given or withheld, in the name of the German state: that of people with names like Habeck.

Steinmeier’s speech at a November 8 roundtable “on peaceful coexistence,” which he convened in the presidential palace at Schloss Bellevue, won plaudits across German media. “I am pleased about the great solidarity with Israel,” Steinmeier intoned. “But I am concerned about how much the violence in the Middle East also endangers social peace in Germany. And I am horrified by the approval of terror and the antisemitic incitement on our streets. . . . It’s like a nightmare that has been holding you captive for a month,” Steinmeier said, “address[ing] the Jewish community in Germany.” He then turned to the “people with Palestinian or Arab roots in Germany.” “There must be no anti-Muslim racism or general suspicion against Muslims,” he warned. “But terrorism, incitement and calls for the destruction of the State of Israel are not part of this guarantee, and I expect us to stand together against it.” While Steinmeier’s address to Germany’s Muslims was far more stern (“Do not let Hamas’s accomplices exploit you! You must speak for yourself! You must clearly reject terrorism!”) than his words to the Jewish community, it’s interesting that he in a formal sense treated the two communities the same. He gave both groups a script to read from.

The conservative journalist Jan Fleischhauer was far blunter. “The Jews or Aggro-Arabs,” ran his article’s headline: “we have to decide which we want to keep.” The majority luxuriates in this feeling of being the one that gets to make the distinction, to adjudicate, to assign everyone their place—and the public feelings, opinions, and performances required to secure any place in the German conversation. There is a glee in disciplining all those thought to have overstepped their place, and these outgroups pointedly include both Jews and Muslims.

In the most perverse way, Germany’s fights over antisemitism appear to be premised on a Germany without Jews. This is the world I grew up in, where we were told about Jews. These were much less noxious stories than those of our grandparents. But they were, in the end, still rumors about Jews—stories with very few actual people to attach them to. In a world where Jews are important but largely absent, philosemitism and antisemitism grow increasingly to resemble one another. Even when they want to embrace Jews, non-Jewish Germans frequently otherize them, or—like Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock—treat them as a “gift” “we” have received (that “we” again). The poet and scholar Max Czollek recently recalled an interviewer who introduced him as having written “three books about the relationship between Germany and Israel.” In fact, Czollek’s books are not about Israel at all, but about being Jewish in Germany. The very ease with which German discourse equates Jewish identity with Israel, and Jewishness with precarity, is in the first instance a failure of imagination. But it is also deeply narcissistic: Jews anywhere must not, cannot be more or different than what their German butchers made them.

For his part, after October 7, Hubert Aiwanger was more than happy to talk about antisemitism—just not his own. “Our immigration policy is one of the main reasons for this development,” he said. Antisemitism, he claimed, was an outside pollutant brought into Germany “from these cultural circles where antisemitism is openly shown and presented.” He was somehow not referring to the Aiwanger household. In the nomenclature of a country still allergic to reflecting on its own multiculturalism, “immigrants” can equally mean people who came to Germany last week or those whose grandparents came seventy years ago, but who happen to have the wrong last name.

Many German intellectuals and journalists were incensed by Aiwanger’s remarks, apparently not noticing that this was precisely the conflation they had collectively enabled over the preceding weeks. They had found antisemitism in all the places they usually look for things they don’t like—the immigrant quarters of Neukölln, US campuses, postcolonial theory, Black Lives Matter. Any consternation at Aiwanger’s shamelessness among German media was only the rage of Caliban seeing his own face in a glass.

In contrast, the consternation and outright hatred that attached itself Judith Butler’s statements, and to the polyphony of voices coming from American Jews, was probably the rage of Caliban not seeing his own face. Because such statements were evidence of a robust, fractious and, most importantly, living dialogue in a Jewish community that, in Germany, has not existed in this shape and diversity since 1933. More, they are evidence that however seemingly inescapable the shadow cast by the Shoah, there are aspects of Jewish life and intellectual traditions where other coordinates are more salient—aspects, that is, to which Germans do not have privileged access just because they are descendants of mass murderers of Jews.

Whatever else it is, coming to terms with the German past is a lot of work. It is uncomfortable, destabilizing. Whatever guidance the categorical imperative “never again” provides is ambiguous; what it commits us to is not always clear. Most frightening today is the sheer fury of Germany’s assertion that, as a country, it best and uniquely understands the lessons of its own murderous past, and the global future of its erstwhile victims. In every invocation of Germany’s unique position, historical responsibility comes to sound more and more like pride.

========

vestment, LLC

======

Again, by Jennifer Koonings, one brightest member CODEPINK Alert

Jennifer Kooning and her friend Samantha, and also another codepink CODEPINK Alert CODEPINK’s Newsletter founding member Ann Wright ann Wright

co founder CODEPINK

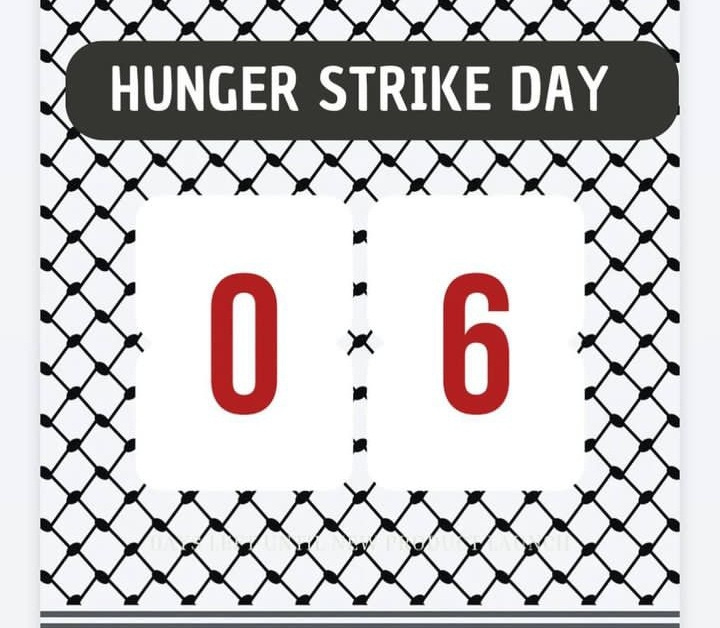

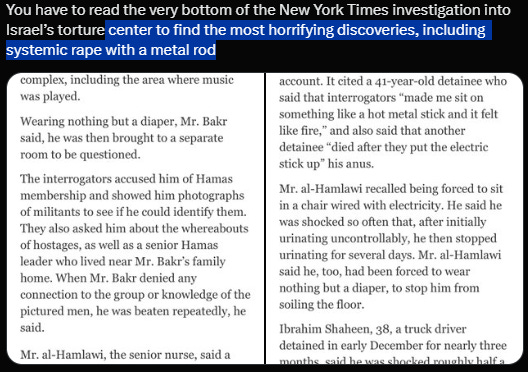

At least 12-13 days Jennifer Koonings, PMHNP, MS, MS, NYSAFE , one brilliant CODEPINK Alert CODEPINK’s Newsletter under Medea Benjamin, hunger strike outside White House in the wake US complicit Genocidal Gaza. This is [click link] her writing as member of CODEPINK Alert CODEPINK’s Newsletter. Jennifer is Certified Forensic Examiner for Adults and Children, really full knowledge about sexual assault, such as sexual assault by Israel to every Palestinian, like NYT reporting [photo uploaded].

We as Muslim prohibited to fasting at least 6 days for entire year [365, or 366 in leap year]. 2 Days Eid Fitr / Eid el-Fitr [1 Shawwal and 2 Shawwal / Syawal Syawwal], Day of Eid Adha / Eid el-Adha [10 Dzulhijjah / Dhul-Hijjah - today], and days of Tashriq [11th, 12th and 13th Dhul-Hijjah / Dzulhijjah, or in Gregorian Calendar 2024, the days of Tashriq means 17-19 June]. But doesn’t mean prohibited for ‘less eating or hunger strike.’ As sacrifice in DC at least 13 days by Jennifer Koonings just because her protest about Gaza, I keep ‘eating less’ not only for her but also for Palestine, at least until 19 June. And for June 20th, back again for nonmandatory fasting, normally 17-18 hours, as even Jennifer, with her gut, sacrifice herself for Gaza. Wisdom quote I hear since war [Israel - Gaza] nonstop ‘’...You can't make people care about a genocide happening right in front of their eyes. They either do immediately, or a chip is missing up there, and they never will.’

For solidarity, since she started to hunger strike, I put myself eat 1 very tiny plate/day for break the fasting and for entire day after, extreme fasting 16.5 hours [based on my location]. I’m still continued for hunger strike, because its very easy. In last 17 years, I already [minimum] 340 days / year to fasting [29 - 30 days for mandatory fasting for muslim, ramadan session, the rest is voluntary fasting / sunnah]. Photo Jennifer with ann Wright, retired retired US Army and also [Ann] retired State Department. Sometimes I’m fasting up to 22 hours / day because forgot to break my fasting.

Medea Benjamin Medea Benjamin Medea’s Substack and Jennifer Koonings Medea Benjamin

footage by CODEPINK Alert CODEPINK’s Newsletter, multiple nurses in DC, after humanitarian duty in Gaza

Please keep donating to [1] PCRF / Palestine Children’s Relief Fund or [2] Freedom Flotilla.

As PCRF pictures by Dr Rajha in Gaza, Ariana Grande - Butera, and CODEPINK Alert

Jennifer Koonings PMHNP, MS, MS, NYSAFE part of CODEPINK AlertJen

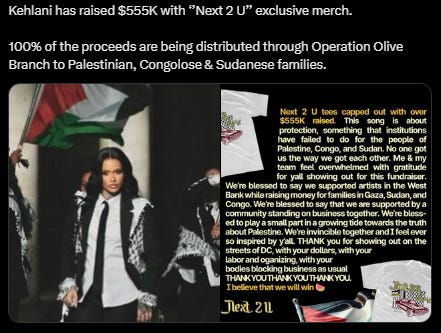

Unlike Israeli and pro zionist student [very easy] get a money [thanks for multiple billionaire], contrary, Palestinian very hard to get a money [like encampments across the world]. Link attached by CODEPINK Alert Jen Jennifer Koonings PMHNP, MS, MS, NYSAFE is Nagham, same healthcare worker like Jennifer but in Palestine. 3 Months ago is Nagham’s birthday. Link to donate. Nagham is still alive.

Jen Jennifer Koonings, PMHNP, MS, MS, NYSAFE. Abdelrahman is still alive after Rafah bombing 3 weeks ago

·

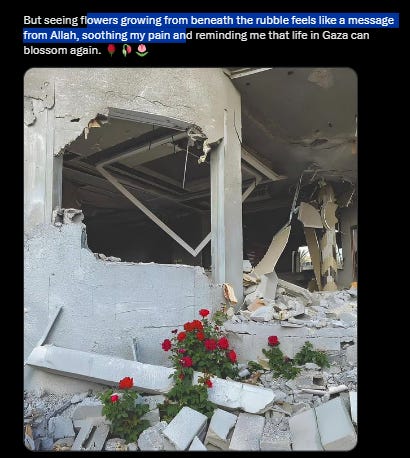

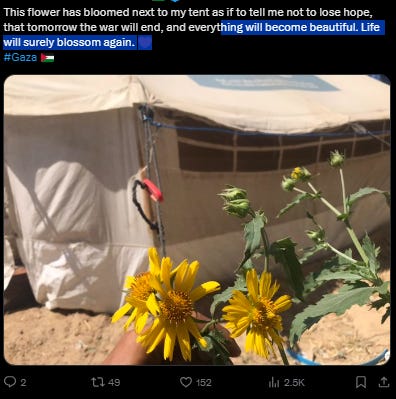

Yellow Flower, Jennifer Koonings in Betlehem [around 3pm local time West Bank, 5 weeks ago], nearly same exact result voting UNGA [11.17am NYC - Rockefeller Building of United Nations], 143 votes in favor, nine against, and 25 abstentions for Palestinian membership.

Footage by mine. Minutes before Jennifer

Jennifer Koonings literally singing also for foundation - charity movement Sing for Hope. How golden heart.

her mine

My mine. Doppelganger cat

Love you, Jennifer Koonings PMHNP, MS, MS, NYSAFE. Dont know how deteriorated of you after Hunger Strike

Thanks for reading Prada’s Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

![Dem Operatives: [Best Hope] 'JOEVER' Biden Died Naturally, Immediately, Better, to 'Change the Horse' Dem Operatives: [Best Hope] 'JOEVER' Biden Died Naturally, Immediately, Better, to 'Change the Horse'](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff7d57ea0-bc62-4f54-8043-64ceeca7124c_470x468.png)

Ho Lee Phuk

Do you think this is the present subject concerning today's attempted genocide and crimes against humanity in Israel connected to World War II?

I don't have words for that level of either intentional disingenuous bullshit or incredibly effort expended level of stupidity.

No connection between the two is the complete irony hypocrisy and moral bankruptcy of the persecuted being the persecutor. The constant victimhood coalition.

Do you really not understand how it is doing besides murdering tens of thousands of innocent women and children is creating more terrorist and more antisemites? Fuck you

October 7 was an obvious and blatant false flag. Please do better