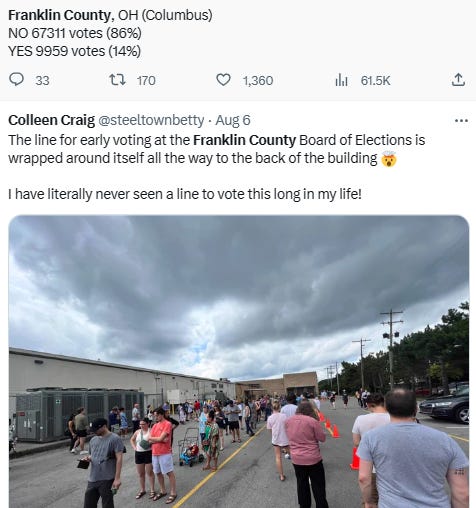

Columbus Ohio 9.33pm

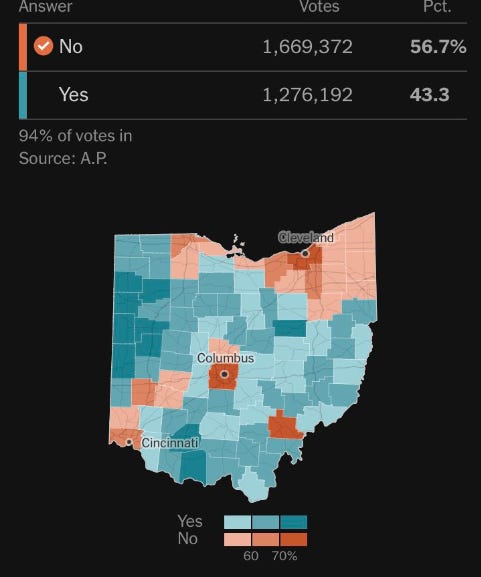

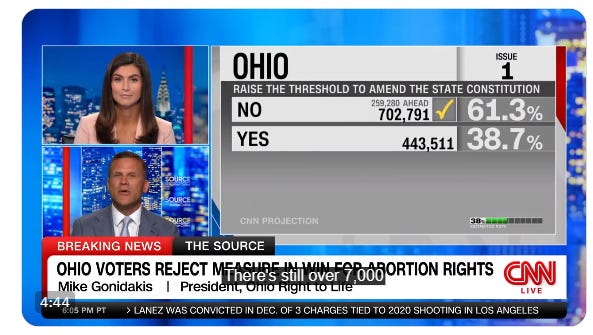

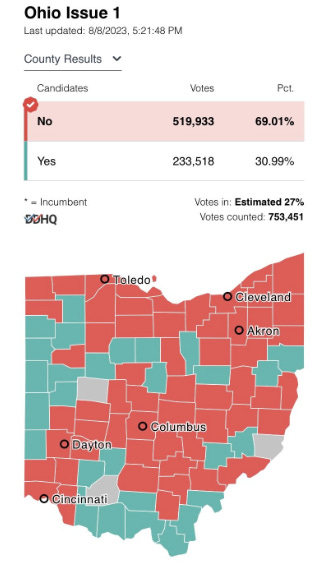

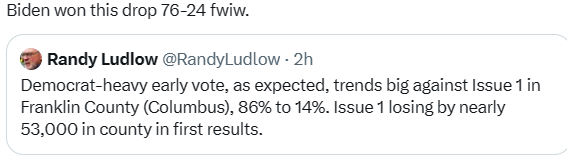

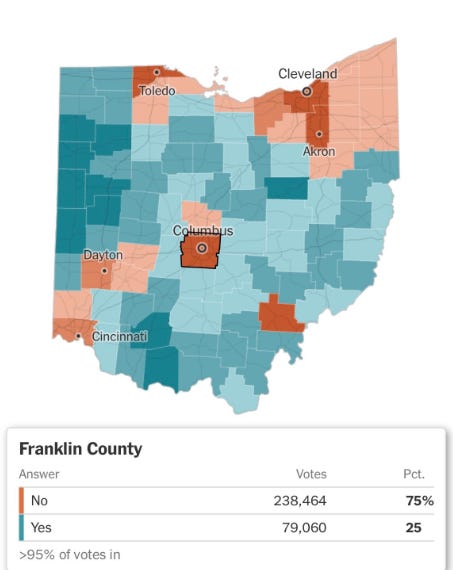

In today’s Ohio special election, voters overwhelmingly defeated (61.3% to 38.7%; won with gap nearly 40% —- votes counted already 1.1 million. but 56.7% to 43.3% when votes counted already 2.92 million / 94%) the Republican-backed ballot initiative known as Issue 1, a measure which would make it harder for voters to amend the state constitution. In a major victory for the pro-choice side, Ohio Issue 1 (a measure to raise the threshold to pass a state constitutional amendment to 60%) fails. The result is a massive victory for efforts to enshrine abortion rights in the state constitution in November and for direct democracy. GOP no longer has confidence in its ability to prevail, said Katie Paris, founder of Red Wine and Blue, a group that organizes for Democratic-leaning suburban women.

Anti abortion group "Protect Women Ohio" spent a $1 million on horrific anti trans ad to get Referendum 1 to pass and limit the ability for abortion rights to be voted into the Ohio constitution. They lost badly. 69-30. Yet again, transphobia doesn't win elections.

Ohio Issue 1 is going to fail in Delaware Co. (northern Columbus burbs), which has voted Republican in every presidential race since 1916 and didn't even vote for Sherrod Brown in 2018. The final Ohio Issue 1 map could end up looking a lot like the 2018 Senate race map, where Sherrod Brown's strength/religious conservatives' weakness with blue-collar voters in eastern Ohio proved decisive.

Ohio has history on its side in establishing itself as not just a battleground, but a must-win state to achieve victory in the presidential campaign. It's flipped back and forth over the last dozen presidential elections, tantalizingly moving left or right just enough to make sure neither party writes it off. Since 1944, Ohioans have selected the losing candidate only once, voting for Republican Richard Nixon over Democrat John F. Kennedy in 1960.

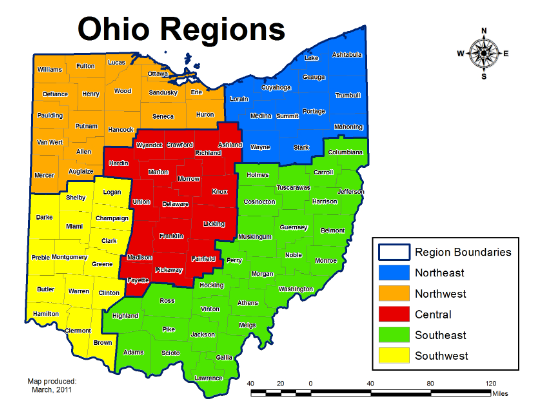

Ohio’s regional diversity is unlike any other state in the country. Many states, it is true, are a mixture of urban and rural areas. Geological features such as coasts, plains, and mountainous areas often divide states as well. Yet, Ohio is perhaps unique in that, while some of these factors are present, the existence of such regional diversity belies a simple explanation for Ohio’s complex political character. As observers and campaign strategists have long known, it is useful to think of the state as having five regions, what have been called the “Five Ohios.” Each region represents a unique collection of big cities, suburbs and rural areas, one or more media markets, and at least one major newspaper. Each region has a distinct political ethos and votes in a different fashion.

The five Ohios are “Northeast,” “Northwest,” “Central,” “Southeast,” and “Southwest” Ohio.

Northeast, Northwest, Central and Southwest Ohio form various kinds of rectangles in their respective “corners” of the states, loosely surrounding the dominant cities of each region. In contrast, Southeast Ohio covers a broad semi-circle along the Ohio River.

Northeast Ohio (including Cleveland) is the most populous part of the state, followed by Southwest Ohio (including Cincinnati) and Central Ohio (including Columbus). In fact, the “three C’s”— Cleveland , Columbus and Cincinnati —play a dominant role in the economic, social and political life of the Buckeye state. Northwest Ohio (including Toledo) and Southeast Ohio contain markedly fewer people and have sometimes been referred as part of the “Other Ohio,”—areas of the state lying outside the “three C’s” corridor.

The regions are quite distinct. For example, Southeast Ohio has the largest white population (95.9 percent) and Northeast Ohio has the smallest (81.4 percent). Professional/managerial occupations are more common in the “three C’s” regions and construction/manufacturing jobs are more common in the “Other Ohio” regions. Meanwhile, Northeast and Southeast Ohio tie for the largest proportion of older citizens, while Central Ohio has the fewest senior citizens. There are also important differences in religious affiliation with Southeast Ohio containing the most Evangelical Protestants and Northeast Ohio having the lowest; an opposite pattern holds for the Catholic population. There is also a large variation in population density across the regions.

Ohio’s regions match the regions of the country as a whole. For instance, Northeast Ohio resembles the country’s Northeast region in relative terms when it comes to the African-American population, population of European ethnicity, and the proportion of Catholics. In contrast, Southeast Ohio resembles the South in terms of poverty and the percentage of Evangelical Protestants. Central Ohio resembles the West in terms of professional/managerial occupations and college degrees. Meanwhile, Northwest and Southwest Ohio resemble the Midwest region as a whole.

When Janet Folger Porter moved back to Ohio in December 2010, she invited some of her closest friends to her new home in suburban Cleveland.

Her guests sipped coffee, made small talk and shared a breakfast of bacon and eggs. Meanwhile, Porter set up a white board in front of the fireplace. On it, the hostess wrote two words: “Heartbeat Bill.”

Porter’s gathering was a business meeting. And Porter, as everyone in the room knew, was in the business of banning abortion.

“This is how we can do it,” she told her guests.

Porter planned to get a law passed that would ban all abortions in Ohio after about six weeks gestation, when embryonic cardiac activity can be detected. There would be no exceptions for rape or incest.

It represented a bold challenge to Roe v. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court decision that guaranteed a right to abortion. If Porter's law passed, it also would be one of the most restrictive abortion laws in the nation, an idea so radical that even Ohio Right to Life and the state’s top Republicans would spend years opposing it.

Yet today, the bill is the law of the land in Ohio. Considering the similar bans enacted in 23 other states after the Supreme Court overturned Roe in a 6-3 decision this summer, Porter’s vision is no longer extreme in the world of Republican politics – it’s the norm.

The story of how a onetime bellwether state like Ohio led a slow, determined push to steadily weaken and then nearly eliminate abortion rights is in many ways a case study for what has happened around the country. Long before the Supreme Court reversed Roe, anti-abortion activists like Porter recognized that demographic shifts and gerrymandered statehouse districts would entrench Republican majorities and allow them to push abortion restrictions that polls show are unpopular with most Americans.

The consequences came just a month after the Supreme Court’s decision, when a 10-year-old rape victim had to leave Ohio for an abortion in Indiana because her pregnancy had gone beyond the six-week limit. Nevertheless, members of Ohio’s Republican-dominated legislature have pressed forward with plans for a near-total abortion ban either this year or next.

“We are often viewed as a bellwether,” said David Pepper, former chairman of the Ohio Democratic Party. “I think we have become a bellwether in how an out-of-control statehouse can basically destroy your state.”

But 12 years ago, as Porter scribbled ideas on the white board, Ohio was a swing state that had gone for Barack Obama and would send a mainstream Republican like Rob Portman and a progressive Democrat like Sherrod Brown to the U.S. Senate. Democrats controlled most statewide offices, including governor.

That Ohio didn’t work for Porter, the founder of the right-wing Christian group Faith2Action. She was a longtime culture warrior who opposed gay marriage, promoted false claims questioning Obama’s birthplace and compared abortion to the execution of children during the Holocaust.

She was tired of watching fellow Republicans settle for measures such as licensing restrictions for clinics and waiting periods for patients – moves that made it harder, but not impossible, to get abortions.

She said in a recent interview that she’s been guided by the words of Martin Luther: “If we are not fighting where the battle is hottest, we are traitors to the cause.”

She told her houseguests it was time to take on Roe. To succeed, they’d launch what amounted to a decadeslong insurgency, a movement to change Ohio politics from the top down.

They’d have to start with their own Republican Party. Over time, the fight would become personal, as Porter and her allies adopted tactics that some said were as divisive as they were effective.

"I wanted them to see, these people are crazy. They're not gonna quit," Porter said. “We were not gonna give up until this bill became law."

Emboldened GOP allows fetuses to 'testify'

About three months after the gathering at Porter’s house, she sat in a packed hearing room at the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus for a March 2011 hearing. The fetuses were ready to testify.

Two pregnant women would take turns on an ultrasound machine set up in the house chamber so lawmakers could see and hear inside their wombs. The hearing was among the first for the heartbeat bill, which a team of lawyers and activists Porter assembled had written in the weeks following the meeting at her home.

The bill would require people seeking abortions to undergo ultrasounds to detect cardiac activity. If it was there – and it usually was at about six weeks – a doctor who performed an abortion would face criminal charges and up to a year in prison.

Democrats, who unanimously opposed the bill, condemned the ultrasound hearing as a shameless stunt.

But there was nothing they could do about it. The Ohio House had flipped to a 59-40 Republican majority after two years of Democratic control. Energized by opposition to the Affordable Care Act and the Tea Party’s anti-government agenda, many of the new Republican members had little in common with Ohio’s moderate Republicans.

This new group of Republican lawmakers helped elect Bill Batchelder – a member of a conservative group of lawmakers known as the "Caveman Caucus" – as speaker of the House, and they were more likely than moderate Republicans to embrace legislation like Porter’s heartbeat bill.

“After Obama, Republicans statewide felt ignored,” said Clarence Mingo, an Ohio Republican and former Franklin County official who has pushed back against extremism in his party. “The result of that was a shift to hard-right conservative thinking.”

Still, the newly remade Ohio GOP was not yet strong enough to impose its will at the statehouse. Some of Porter's fellow Republicans worried the courts would reject her six-week ban as unconstitutional, potentially strengthening Roe instead of weakening it. And they feared moderate voters might object to such strict abortion limitations.

Porter had little patience for Republicans who didn’t share her zeal for the cause. “They’re pro-life pretenders,” she said. “They use babies to get elected instead of using elections to save babies.”

As the House opened hearings on her bill, Porter and her team flooded the offices of Republican lawmakers with calls and emails. In the months to come, they’d send them red balloons shaped like hearts, teddy bears that played a heartbeat recording, and more than 2,000 red roses with cards that said, “Bring this bill to a vote before the roses and babies die.”

But she expected that the fetus testimony would have the greatest impact.

When the hearing began, one of the pregnant women took a seat near a large video screen. She leaned back in the chair, a hospital gown covering her torso, as a nurse ran an ultrasound wand over her belly.

The lights dimmed and a fuzzy, black and white image of a fetus appeared on the video screen. Someone aimed a laser pointer at the pulsing tissue in the center of the picture.

The hearing room was silent – except for a rapid dub-dub-dub that matched the rhythmic movement on the screen.

Everyone was watching and listening. Porter had a master’s degree in communications and had done plenty of public relations work in her career, including for Ohio’s Republican governor, John Kasich. But she’d rarely seen anything grab people’s attention like this. Even a Democratic House member who opposed the bill said the presentation brought back fond memories of her own pregnancy.

Porter was thrilled.

“What we saw today was the beating hearts of these babies,” she told reporters after the hearing.

To save those babies, she said, lawmakers needed to pass her bill.

She felt certain it was just a matter of time.

Clinic lawyer fears Ohio's turn to the right

Aweek later, civil rights lawyer Al Gerhardstein walked into the same hearing room to deliver a different message.

A Cincinnati resident who’d spent much of his career defending abortion clinics, Gerhardstein knew Porter’s six-week ban violated the constitutional standard set by Roe. He also knew that was the point.

This was Ohio, after all, the birthplace of Right to Life and a frequent testing ground for anti-abortion legislation.

For years, Gerhardstein had watched activists like Porter chip away at Roe in Ohio’s legislature and courtrooms, imposing rules like 24-hour waiting periods, mandatory ultrasounds and limits on the use of pills to induce abortion.

This death-by-a-thousand-cuts approach was the brainchild of John and Barbara Willke, a Cincinnati couple who founded the nation’s first Right to Life chapter in the late 1960s. The Willkes weren’t firebrands like Porter. They were devout Catholic grandparents who lectured college students about abstinence, went on "Donahue" to talk about fetal development and came up with billboard slogans like “Abortion stops a beating heart.”

But the Willkes, who mentored Porter when she was a budding activist in college, also worked behind the scenes, writing anti-abortion laws and lobbying politicians to pass them. Their mission was to keep up a steady attack on Roe – one voter, one law, one court ruling at a time.

“It was a brilliant strategy,” Gerhardstein said.

While he respected the Willkes’ approach, Gerhardstein fought them at every turn, representing Planned Parenthood and other abortion clinic operators. To him, the clinics were more than clients. They were on the front lines of a battle to protect a woman’s right to make decisions about her own health and body.

Born and raised Catholic, Gerhardstein appreciated the religious and moral objections to abortion, especially among Catholics who formed the vanguard of the early Right to Life movement.

Yet he also felt the government shouldn’t impose those beliefs on millions of women who wanted for themselves something different.

Before his first case involving an abortion clinic in the 1980s, Gerhardstein called his mother, Carolyn, who had worked for years in Catholic hospitals as an obstetrics and gynecology nurse. He asked how she felt about him taking on the case.

He said she told him she was glad he was doing it. She’d seen many patients, before Roe, who’d been victims of botched abortions they’d attempted on their own or with unqualified practitioners. By the time some got to the hospital, they were in terrible shape.

“It wasn’t about some abstract right,” Gerhardstein said of how his mother viewed the abortion debate. “It was about what she saw.”

Activists like Porter were aggressively going after that right. Even John and Barbara Willke, who died in 2015 and 2013, respectively, abandoned their incremental approach and supported Porter’s push for a six-week ban years before Right to Life and others would follow suit.

Gerhardstein saw the rationale behind the shift. Ohio was moving to the right. Republicans now controlled not only the statehouse, but the redistricting process that would allow them to gerrymander districts and tighten their grip on power. The heartbeat bill, Gerhardstein believed, showed that Republicans planned to use that power to topple Roe at the Supreme Court.

“This was the final plunge,” he said. “It was a direct attempt to challenge the constitutionality of Roe v. Wade.”

Gerhardstein began his testimony at the hearing in 2011 by warning lawmakers the bill they were considering was unconstitutional. But he also urged them to think about the consequences if the heartbeat bill ever became law and Roe one day fell.

It would strip away a woman’s right to follow her doctor’s advice, he said, or even to follow her conscience. It would replace her judgment with theirs.

“Trust women to make their decisions,” Gerhardstein said.

A moderate pushes back on 'no exceptions'

When Stephanie Kunze came to Columbus as a freshman member of the Ohio House in 2013, the heartbeat bill was stuck. It had passed the House two years earlier, but that’s as far as it got.

Republicans in the Ohio Senate refused to bring it to a vote, and Gov. Kasich said he’d veto the bill if it ever reached his desk. They said the bill wouldn’t survive a court challenge and would mire the state in costly litigation for years.

Kunze, a Republican from suburban Columbus, who describes herself as “pro-life with exceptions,” had her own problems with Porter’s bill – mainly the lack of exceptions for rape, incest or serious fetal abnormalities. It was, she said, “an impractical way to legislate something that’s important to families and women.”

Kunze, the mother of two daughters, was passionate about curbing infant mortality and advocating for survivors of sexual violence. But when she arrived at the statehouse, the heartbeat bill was getting most of the attention.

Porter was lobbying hard for another vote in the House so she could try again to get the Senate and Kasich on board. She had enough votes to win, but not enough to override a Kasich veto.

That increased pressure on moderate Republicans like Kunze. Without getting them on board, Porter’s bill couldn’t get past the governor.

Most of Kunze’s Republican colleagues in the House didn’t share her concerns about the bill and were in no mood to compromise.

After the 2012 elections, they didn’t have to.

While Kunze’s House district was politically competitive, redistricting had placed many of her fellow Republicans in safe districts, where primary elections were the only elections that mattered. In those districts, voters who represented the activist wing of the Republican party often rewarded politicians for stances that once seemed radical.

“Extreme gerrymandering is so toxic,” said Kathleen Clyde, a Democrat who served in the House from 2011 to 2018. “It gives legislative leaders this outsized view of their own place in our government and of their own power.”

But there was little Democrats could do. Republicans controlled the redistricting process, and now those same Republicans were dealing with a new political dynamic: Ohio’s most consequential legislative battles no longer were being fought by Democrats and Republicans, but by conservative Republicans and more-conservative Republicans.

Those fights intensified as Republican lawmakers debated Kasich’s 2013 budget, clashing on issues from Medicaid expansion to a new oil tax. They then packed several new abortion restrictions into the budget late in the process, with no time for public input.

One measure required abortion providers to perform ultrasounds and predict the fetus’ likelihood of surviving to full term.

Abortion rights activists erupted. They swarmed the statehouse, shouting, “Shame on you!” as Republican lawmakers approved the abortion measures. They then bombarded Kasich’s office with 17,000 letters urging him to veto them.

The governor let the new restrictions stand, giving abortion hard-liners almost everything they wanted. Kunze, who voted for the budget, called it one of the most “pro-life” budgets in state history.

But it didn’t include the heartbeat bill.

That meant Porter and her allies soon would be back, trying again to flip moderate Republicans to secure a veto-proof majority.

Porter made a list. And Kunze’s name was on it.

Turning up the pressure: No more 'Mr. Nice Guy'

The way Porter saw it, Republicans were wasting an opportunity. By early 2015, they held lopsided majorities in both the Ohio House and Senate, and voters had overwhelmingly sent Kasich back to the governor’s office for a second term. They could do what they wanted.

Yet Senate President Keith Faber wouldn’t bring her heartbeat bill to a vote; Kasich still vowed not to sign it; and Ohio Right to Life still wouldn’t get behind it.

Porter was sick of it. These Republicans had been running for years on anti-abortion platforms. They were, in Porter’s view, hypocrites and liars. No better than Democrats, who at least didn’t pretend to be on her side.

She and her top lieutenant, Lori Viars, decided to get tougher.

“Playing Mr. Nice Guy wasn’t helping,” Viars said. “We had to make their lives miserable.”

Republicans who didn’t back the bill, like Kunze and Kasich, found themselves on online lists under the headline, “Meet the Republicans responsible for abortion in Ohio.”

Direct mail campaigns featuring photos of rhinos accused them of being RINOs, or Republicans In Name Only. Television ads and emails lampooned them, and their voicemail boxes filled with messages from Porter’s allies. Some faced primary challenges from candidates Porter endorsed.

Porter had helped make strict abortion restrictions a fundamental principle of Ohio’s Republican Party, and accusations of being insufficiently anti-abortion could be fatal in a GOP primary.

“Every Republican lawmaker in the state can tell you who is their Right to Life group in their district,” said Aaron Baer, president of the Center for Christian Virtue.

The primary challenges may have been Porter’s most effective weapon. Over several election cycles, she rounded up candidates to run at least a dozen times against members of the House and Senate in Republican primaries.

When she couldn’t find someone to run in the primary against Republican State Senator Larry Obhof in 2016, Porter did it herself.

Neither she nor her endorsed candidates ever won, but that wasn’t the only goal. The real purpose, Porter said, was to make abortion a campaign issue and to force Republicans to spend cash to defend seats they thought were safe because of redistricting.

“They hate working to keep their job,” Porter said. “We made them pay for their inaction.”

She also did her best to embarrass them. Her most creative attack was a 2014 TV ad that took aim at Kasich, Faber and Batchelder, who at the time was reluctant to bring the heartbeat bill up for another vote in the House.

Days after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June, a 10-year-old girl from Ohio became a cautionary tale for life in a post-Roe America.

She’d been impregnated by her rapist and sought an abortion. But at just over six weeks, she was beyond the limit imposed by Porter’s heartbeat bill. She and her family traveled to Indiana for treatment.

Abortion rights activists made her case a rallying cry, and President Joe Biden lamented the cruelty of Ohio’s law, which went into effect now that Roe had been overturned. Republicans, meanwhile, questioned the girl’s story and suggested that journalists made the whole thing up.

“Another lie,” tweeted Jim Jordan, a U.S. congressman from north-central Ohio.

“There is not a damn scintilla of evidence,” Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost said.

The girl’s tragic story was confirmed days later, when the man accused of raping her appeared in court.

Porter maintained that her heartbeat bill had produced a desired outcome.

"We punish rapists, not babies,” she said. “There's no reason to execute an innocent child for the crime of her father."

Porter noted that Ohio’s six-week ban allows exceptions if the woman’s life is in danger, but some have questioned how those exceptions would be approved and whether a 10-year-old could get one.

Lost in the uproar over this one girl’s case was the fate of hundreds of others whose lives had been upended by the fall of Roe and the imposition of Ohio’s six-week abortion ban.

After years of worrying about the threat to Roe, abortion providers struggled to adapt to an America without it. “It’s not theoretical anymore,” said Catherine Romanos, a doctor at a Dayton clinic.

Clinics had to cancel scheduled abortions with barely a day’s notice. Women scrambled to find alternatives. Burkons said he had to cancel a scheduled abortion for a 15-year-old girl who’d come with her mother to his clinic the previous week. She was 13 weeks pregnant. He never heard from her again.

He’s also unsure what happened to many of the patents who’d left his office with abortion-inducing pills in lockboxes the day before Ohio’s ban went into effect. If they were more than six weeks pregnant, Burkons wasn’t allowed to give them the codes to unlock their boxes the next day.

Some begged for the numbers, he said, but he couldn’t help. Ohio’s new law wouldn’t allow it.

Burkons said many of the lockboxes that were supposed to be mailed back to him never arrived.

“I have a feeling there were people who took hammers and chisels to the boxes,” he said.

Not done yet: Republicans consider a total ban

Today, almost four months after the fall of Roe, Ohio remains a bellwether in the nation’s abortion wars.

The state’s six-week abortion ban, still known to many as the heartbeat bill, is again tied up in court. A common pleas judge in Cincinnati halted enforcement in September, saying Ohio’s constitution may protect health care decisions like abortion. Yost, the state attorney general, is appealing that decision.

In the days after Roe was overturned, Ohio Republicans began discussing the possibility of a total ban on abortions in Ohio. Critics of the Supreme Court's decision warned of harsher action to come and decried Justice Clarence Thomas's concurring opinion, which seemed to raise the possibility that same-sex marriage and access to contraception could be banned under the same legal principle that toppled Roe.

More recently, with the midterm elections looming, Republican politicians on the ballot have largely stayed silent on abortion restrictions. Polls show most Americans – and most Ohioans – oppose restrictions like Ohio’s six-week ban.

Not all conservatives are hesitant to talk, though. Porter continues to speak about the need for tougher abortion laws, while also promoting conspiracy theories about a stolen 2020 election and that Trump remains the “real and rightful” president.

At the Christian Patriot Rally in Houston in September, Porter spoke in front of a video screen that displayed giant, side-by-side photos of President Biden and Adolf Hitler.

For Porter, though, the political fights always are in service of her primary mission.

“There’s nothing that compares with the importance of that issue,” she said of banning abortions.

After the Supreme Court overturned Roe, Porter threw a party in the same house where she and her guests conceived the heartbeat bill more than a decade earlier.

A celebratory banner still hangs on the wall: Roe is dead. Babies will live. Thank you, Jesus.

But the excitement that day wasn’t just about the Supreme Court’s ruling. It was about what comes next.

In Ohio, anything seemed possible.

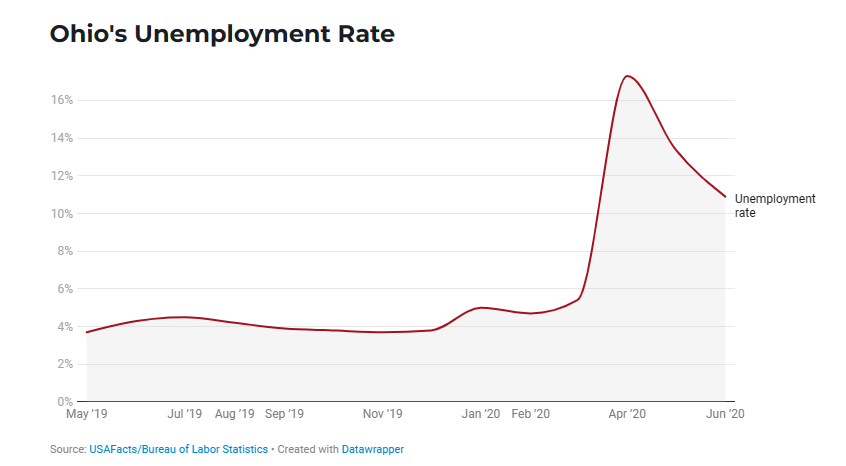

Ohio’s labor force was among the hardest hit by the coronavirus pandemic – only five states recorded higher unemployment rates in April. The state recorded its highest unemployment rate since state unemployment data began in January 1976.

Bill Clinton took Ohio in 1992 after a campaign where the Democratic nominee commiserated with those middle-class voters who, he said, had "played by the rules and gotten the shaft." Former First Lady Hillary Clinton, however, failed to connect with those voters. Clinton won just a single income group in Ohio – the very lowest-income, those making $30,000 a year or less – and lost the white male, non-college-educated vote, with 25% of that vote to Trump's 71%, according to exit polls.

Trump went after trade deals, globalization and the movement of jobs overseas – all matters that resonated deeply with voters in Ohio. He nearly swept the counties in Ohio's Southeast corner, while turnout was somewhat depressed in urban areas that tend to vote Democratic. If there was a place where Trump's nostalgic "Make America Great Again" message hit home, it was in Ohio.

But that was when Trump was a new candidate, an outsider who ridiculed the efforts earlier officials had made to save the faltering coal and steel industries. As president, Trump is running on his record, and that is problematic for him in Ohio.

In July 2017, Trump, then in his first, heady year of being president, went to Youngstown, Ohio, 15 miles from General Motors' Lordstown Assembly plant in Warren. "Don't move. Don't sell your house," Trump implored, promising he'd protect the manufacturing jobs in the area. A year and a half later, GM announced it would "unallocate" five North American plants, including Lordstown – the first step toward closure. In September 2019, the Ohio plant closed for good.

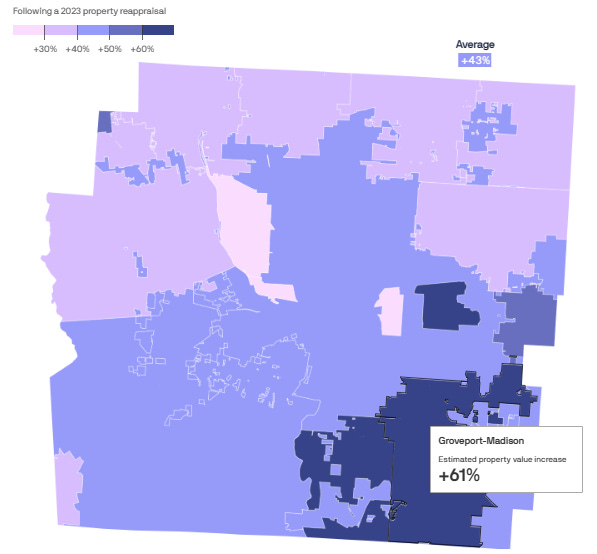

Following a 2023 property reappraisal. Franklin County home values will increase by historic levels following this year's countywide property reappraisal, a process that happens every six years based on Ohio law.

Your home's appraised market value impacts how much you pay in property taxes, plus how much you could sell it for. This is the first full reappraisal since the pandemic-fueled housing boom that spiked demand for area homes — and prices — to unprecedented highs.

Ohioan can check yhome's new value on the Franklin County auditor's website and view your estimated new tax bill. Letters will also be mailed later this month.

By the numbers: On average, home values are expected to increase 43% across Franklin County this year, though the amounts will vary significantly between school districts. Traditionally more affordable districts will have the largest jumps, as they're starting from lower price points: Hamilton (70%), Whitehall (68%) and Groveport-Madison (61%).

=========END————

Thank you, as always, for reading. If you have anything like a spark file, or master thought list (spark file sounds so much cooler), let me know how you use it in the comments below.

If you enjoyed this post, please share it.

______________

If a friend sent this to you, you could subscribe here 👇. All content is free, and paid subscriptions are voluntary.

——————————————————————————————————

-prada- Adi Mulia Pradana is a Helper. Former adviser (President Indonesia) Jokowi for mapping 2-times election. I used to get paid to catch all these blunders—now I do it for free. Trying to work out what's going on, what happens next. Arch enemies of the tobacco industry, (still) survive after getting doxed. Now figure out, or, prevent catastrophic situations in the Indonesian administration from outside the government. After his mom was nearly killed by a syndicate, now I do it (catch all these blunders, especially blunders by an asshole syndicates) for free. Writer actually facing 12 years attack-simultaneously (physically terror, cyberattack terror) by his (ex) friend in IR UGM / HI UGM (all of them actually indebted to me, at least get a very cheap book). 2 times, my mom nearly got assassinated by my friend with “komplotan” / weird syndicate. Once assassin, forever is assassin, that I was facing in years. I push myself to be (keep) dovish, pacifist, and you can read my pacifist tone in every note I write. A framing that myself propagated for years.

(Very rare compliment and initiative pledge. Thank you. Yes, even a lot of people associated me PRAVDA, not part of MIUCCIA PRADA. I’m literally asshole on debate, since in college). Especially after heated between Putin and Prigozhin. My note-live blog about Russia - Ukraine already click-read 4 millions.

=======

Thanks for reading Prada’s Newsletter. I was lured, inspired by someone writer, his post in LinkedIn months ago, “Currently after a routine daily writing newsletter in the last 10 years, my subscriber reaches 100,000. Maybe one of my subscribers is your boss.” After I get followed / subscribed by (literally) prominent AI and prominent Chief Product and Technology of mammoth global media (both: Sir, thank you so much), I try crafting more / better writing.

To get the ones who really appreciate your writing, and now prominent people appreciate my writing, priceless feeling. Prada ungated/no paywall every notes-but thank you for anyone open initiative pledge to me.

(Promoting to more engage in Substack) Seamless to listen to your favorite podcasts on Substack. You can buy a better headset to listen to a podcast here (GST DE352306207).

Listeners on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Overcast, or Pocket Casts simultaneously. podcasting can transform more of a conversation. Invite listeners to weigh in on episodes directly with you and with each other through discussion threads. At Substack, the process is to build with writers. Podcasts are an amazing feature of the Substack. I wish it had a feature to read the words we have written down without us having to do the speaking. Thanks for reading Prada’s Newsletter.

Wants comfy jogging pants / jogginghose amid scorching summer or (one day) harsh winter like black jogginghose or khaki/beige jogginghose like this? click

Headset and Mic can buy in here, but not including this cat, laptop, and couch / sofa.