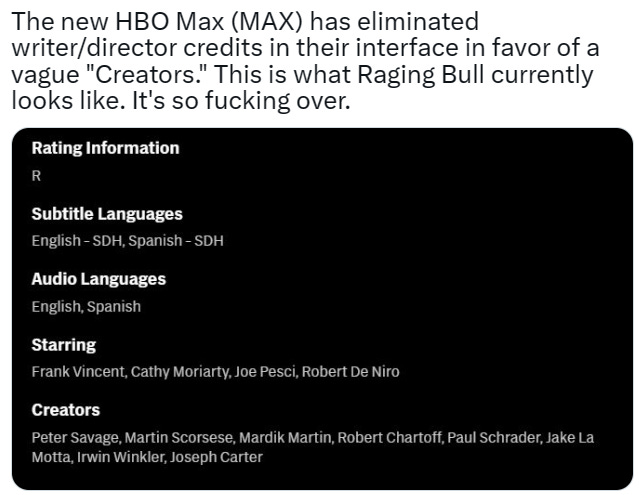

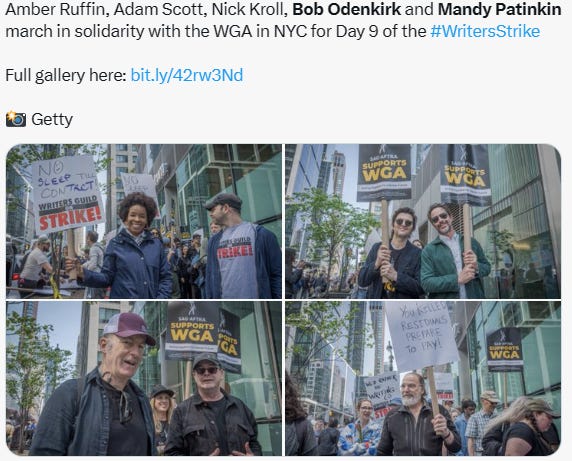

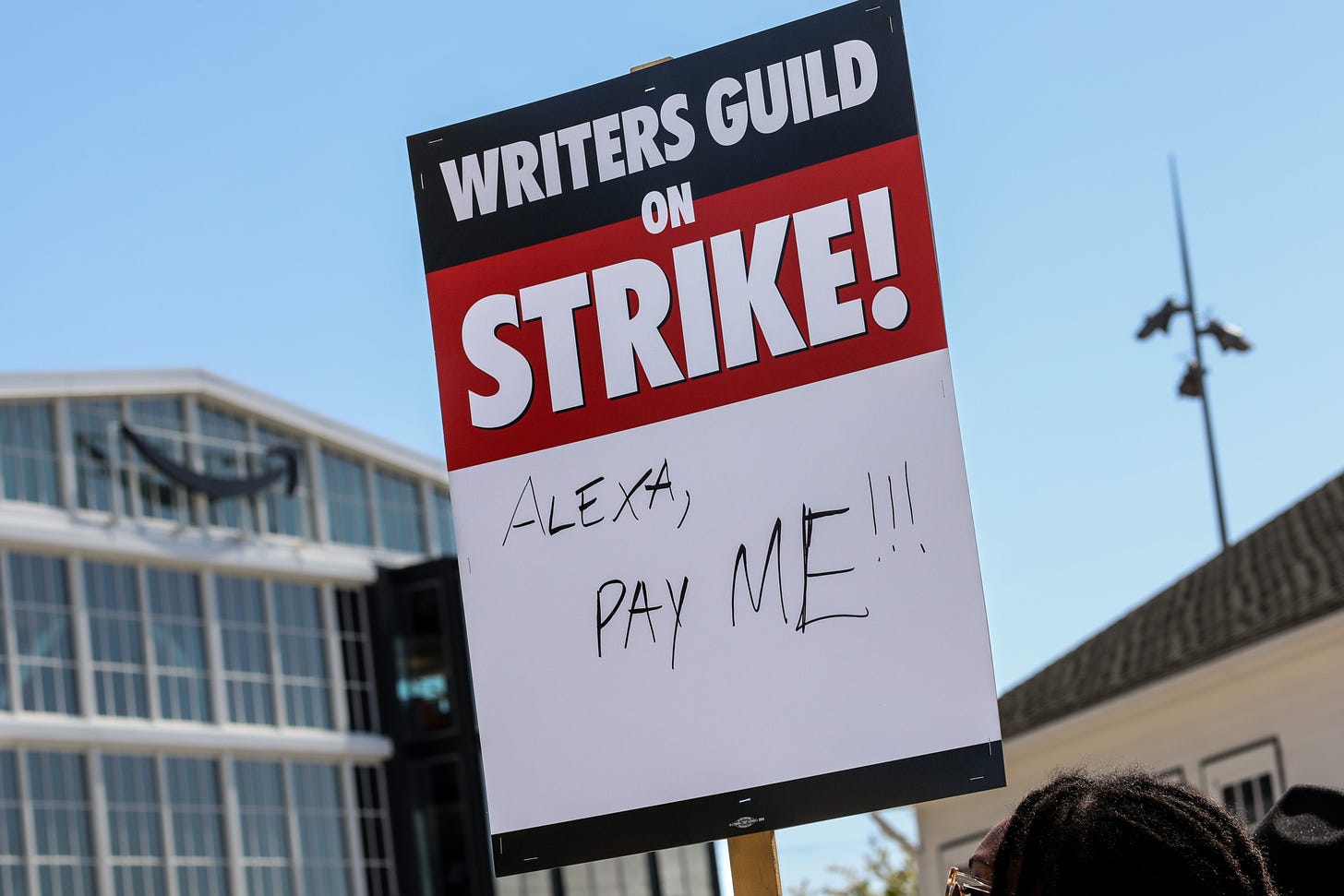

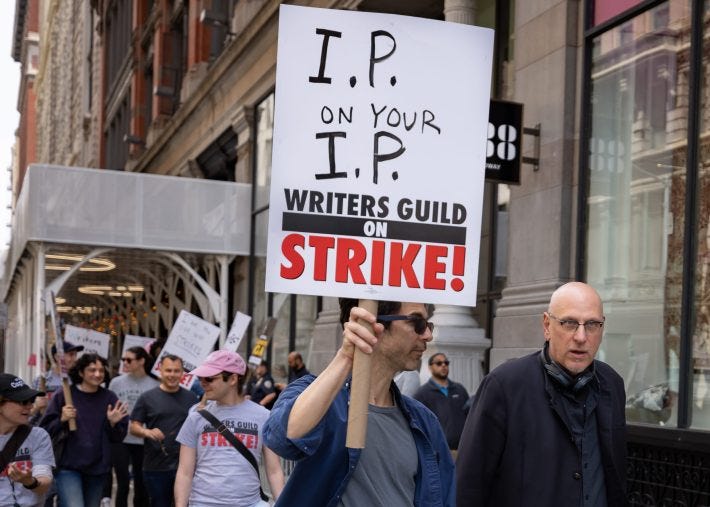

If you are praising SUCCESSION, you must admit paying better for the writers: 2023 Writers Strike (and still striking)

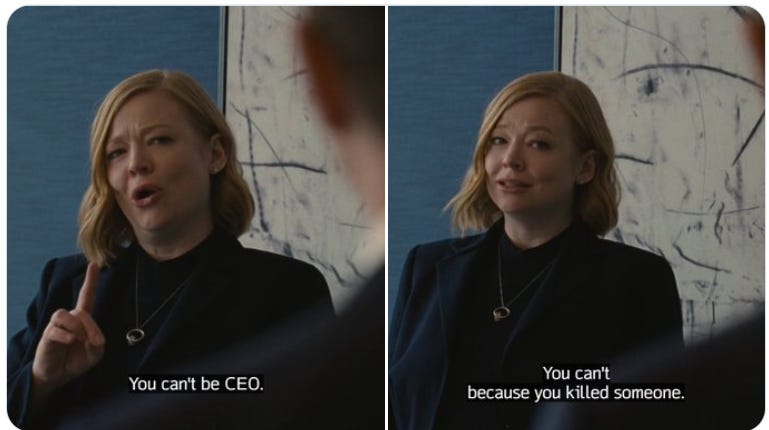

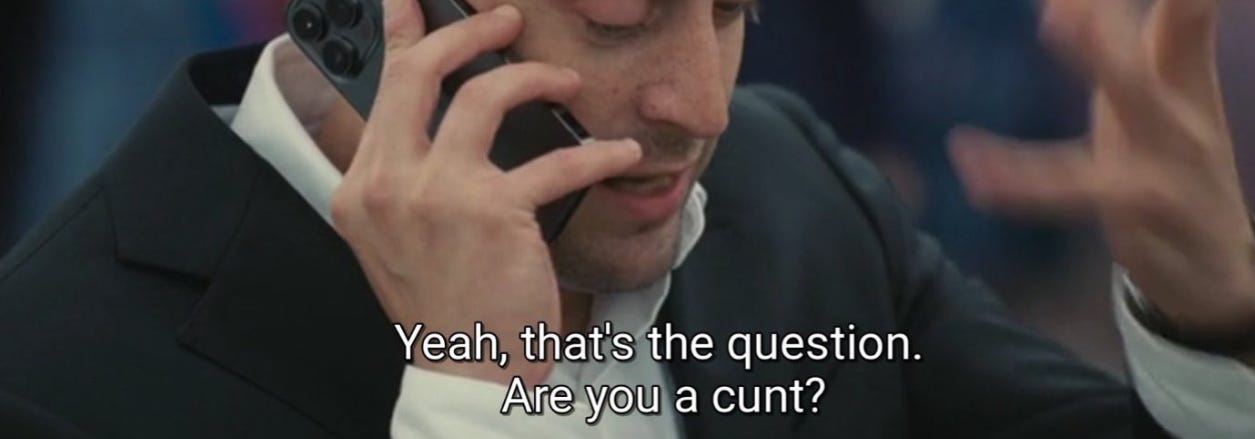

"You can't be CEO. You can't because you killed someone." (Shiv Roy / portrayed by Sarah Ruth Snook).

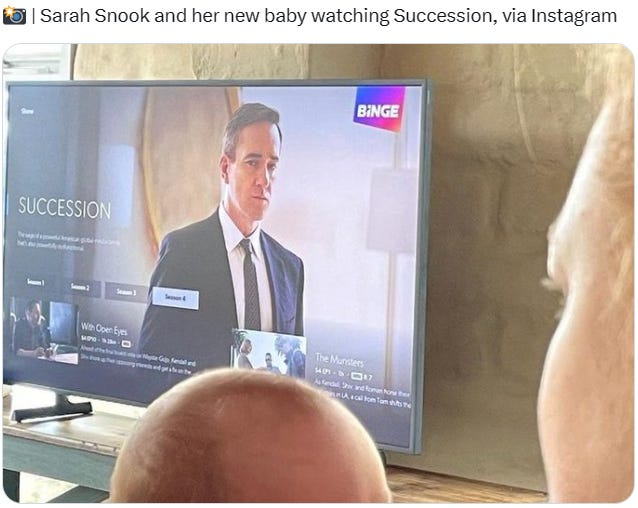

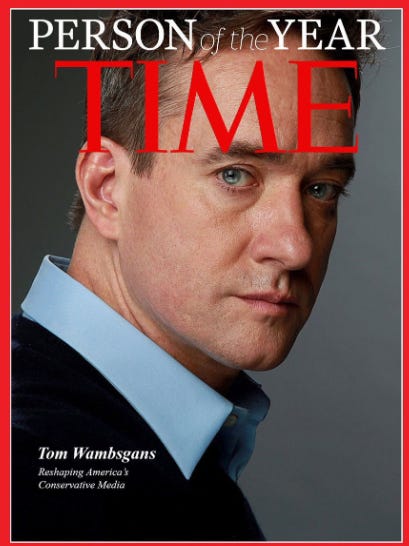

It’s over. It’s done. I don’t think we’ll see a TV show, or a cast, or acting, or writing, like that, again, in the near future, same par with 24, Billions, Homeland, Brooklyn 99. Thank you to Jesse Armstrong and his SUCCESSION amazing team for giving us this gift.

We must praise entire (not only Jess) Succession writers. Jessie Armstrong, Jamie Carragher, Susan Soon He Stanton, Alice Birch, Miriam Battye, Georgia Pritchett, Tony Roche, Nathan Elston, Jon Brown, Callie Hersheway, Will Tracy, Lucy Prebble, Jonathan Glatzer, Ted Cohen, Anna Jordan, Mary Laws, Will Arbery. Good movie(s), good series, good script, and we must care about Writer’s Right: good salaries, fair salaries in the wake catastrophe debt ceiling.

A solid series finale takes its time to get to the penultimate scene. It doesn’t feel like the creators are cramming in new ideas and racing to tie up every loose end because they know this is it. The Succession finale deftly unfolds with just what we need to be satisfied. Succession ends as arguably [HBO] Max’s biggest show. Certainly, WarnerMedia executives would have gladly squeezed another four seasons out of the show. That creator Jesse Armstrong stood up for his characters and made certain it ended strongly is on its own a powerful statement.

"You can't be CEO. You can't because you killed someone." (Shiv Roy —- portrayed by Sarah Ruth Snook). According to research by National Library of Medicine, sustained low-wage earning may be associated with elevated mortality risk and excess deaths, especially when experienced alongside unstable employment. Poor quality employment is the main issue for global labour markets, with millions of people forced to accept inadequate working conditions, according to a new report from the International Labour Organization (ILO).

As Kendall Roy (Jeremy Strong) sat sad and bewildered in Manhattan’s Battery Park after Tom Wambsgans (Matthew Macfadyen) became the successor that Logan Roy and his children never wanted or planned on occupying the big chair at Waystar Royco, fans posted and reacted to Sunday night’s series finale of HBO’s drama “Succession” with laughter, sadness and appreciation for what the show accomplished with its last episode Unlike Roman Roy (Kieran Culkin), no one had pre-grieved the loss.

And the same question that followed other prestige shows of TV’s recent golden era now confronts “Succession”: Did it offer a satisfying end?

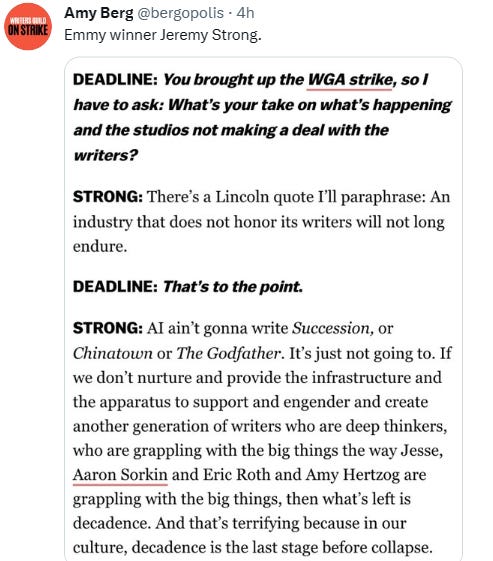

AI cannot replace (talented like) Jesse and another writer. AI ain’t gonna write Succession. (Please) Appreciate (better) to the writers. Fair salaries.

SUCCESSION in ….. HBO (too)

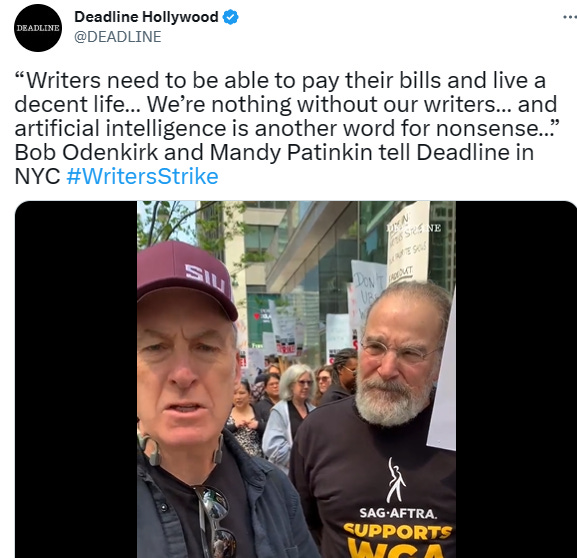

Duo Saul’s. Saul Berenson (Mandy Patinkin) and Saul Goodman (Bob Odenkirk)

For the past three years, low-income workers have made historic gains in wages even after inflation, reversing the trend of advances for upper-income workers and stagnating pay for laborers that dominated the previous four decades.

The gains were the product of a series of dramatic changes in the structure of the labor market and government policies to aid the economy during the pandemic. Fueled by the resulting worker shortage, for example, one of the lowest tiers of earners — people making an average of $12.50 per hour nationally — saw their pay grow nearly 6 percent from 2020 to 2022, even after factoring in inflation. That’s significantly bigger than what low-wage workers got during the entire administration of President Barack Obama, following the Great Recession.

At the same time, price spikes have eaten away raises for the highest-earning employees, leading their inflation-adjusted income to drop roughly 5 percent over the past couple of years. The result, according to one new paper: One-quarter of the 40-year growth in the yawning gap between higher-income workers and lower-income workers has disappeared in just a few years.

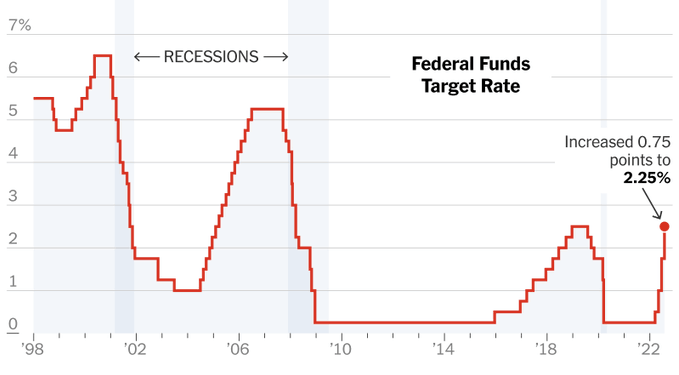

Now, however, those gains are in jeopardy, as the government moves to end bipartisan pandemic-era spending that injected trillions of dollars into the economy, spurred consumer spending and put workers in ultra-high demand. The Federal Reserve has been moving to slow down the economy, worried that wages for all workers are rising too fast for inflation fall back down to their goal of 2 percent and enacting a series of interest-rate hikes designed to curb economic activity.

The resulting slowdown will hurt low-wage workers disproportionately. In recent months, the number of people quitting their jobs and the number of vacancies posted by employers have drifted downward, suggesting less mobility and fewer opportunities for wage growth.

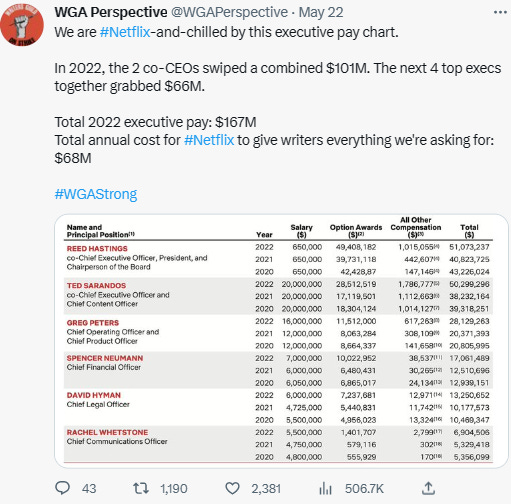

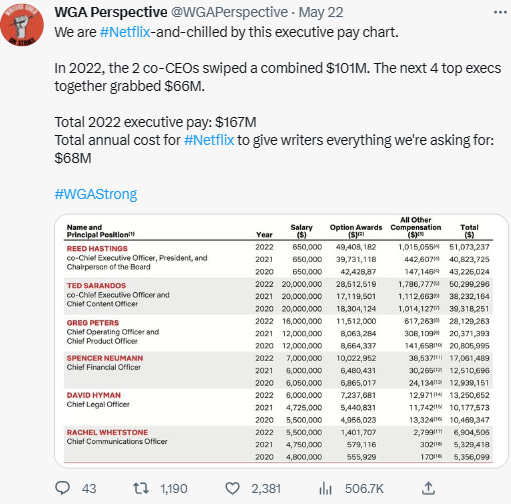

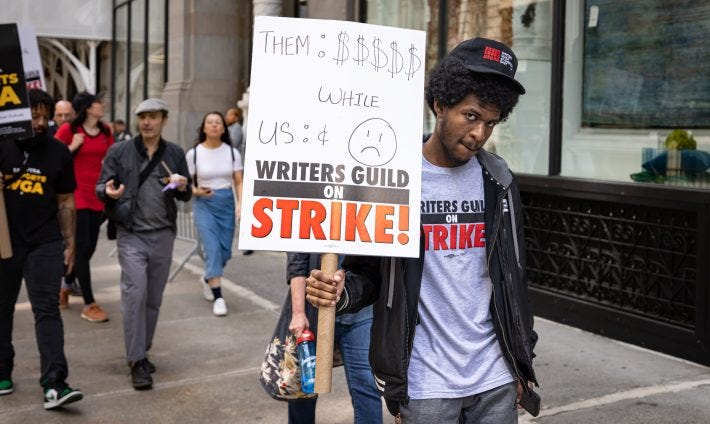

(get multi-billion dollar for gigantic streaming across the globe but pay too low salaries for writers?)

This presents a clear inflection point for the Biden administration and its allies in Congress. While the administration has been largely supportive of the Fed’s moves as households strain under the burden of inflation, progressive lawmakers and economists have questioned whether progress for low-wage workers is being sacrificed in pursuit of price stability.

Some Democrats have expressed frustration, or even outrage, at Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s willingness to allow joblessness to rise, even as unemployment still sits at modern-era lows at 3.4 percent.

“For the first time in a long time, workers have gained some power in the economy,” Senate Banking Chair Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio). “Wages and employment numbers are the best we’ve seen in decades. We can’t erase those gains by cutting workers’ jobs or wages in the name of bringing down inflation.”

That tension is likely to play out over the next few months as the Biden administration hones its economic message for 2024: Fearful of alienating middle-income voters struggling against inflation, will Democrats portray the economy as a work-in-progress, still recovering from the shock of the pandemic? Or will President Joe Biden stress the gains for low-income workers as counteracting the long-running narrative of winner-take-all benefits for the wealthy?

There is statistical evidence for both messages.

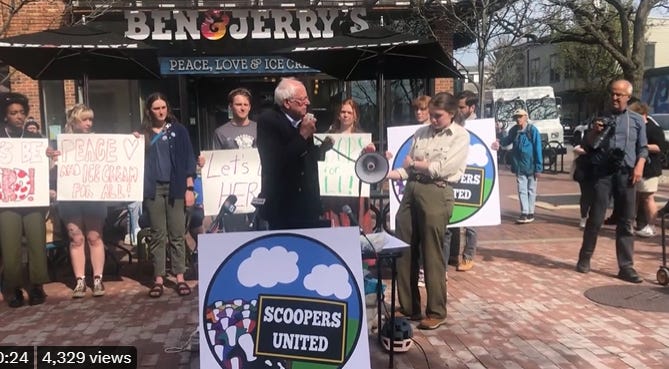

In recent years, people in service industries like restaurants, hotels and retail were able to move into better-paying jobs, leaving the workers who took their place with more leverage to push for higher wages and better benefits. Organized labor gained power at the bargaining table, with unions like UNITE HERE, which represents food, hotel and casino workers, pointing to an extensive list of wage wins in workplaces across the country.

“I’d love to say we’re the greatest negotiators in the world,” said D. Taylor, who heads the union, but “there’s never been a better time to organize.”

The data show rapid gains from the last 10 months of Donald Trump’s presidency and the first 14 of Biden’s; since then, both wage and price growth have cooled in the wake of aggressive interest rate hikes by the Fed.

Inflation-adjusted income for the 10th percentile of the workforce — the ones earning an average of $12.50 per hour nationally — surged by 5.7 percent from March 2020 to March 2022, according to the Labor Department’s Employer Costs for Employee Compensation index, which tracks pay for the same positions at the same employers over time.

That number is particularly striking when compared to the 3.9 percent raise the same cohort saw from 2009 to 2017 — which amounts to less than half-point gain per year. Even from 2017 and 2019, when the job market was at its healthiest in decades, low-wage workers saw their pay increase only by 3.1 percent after factoring in inflation, which at the time was quite low.

“Fundamentally, in the post-pandemic period, we’ve seen a major restructuring of the low-wage labor market,” said Arin Dube, a professor at University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Dube, along with two co-authors, dug through Census Bureau data and found that the gains were particularly strong for non-college-educated workers under the age of 40 between January 2020 and September 2022. That raises the possibility that younger generations will fare better than millennials, who entered the workforce in the wake of the Great Recession at low pay, dragging down their potential lifetime earnings.

“What that does is, it changes how quickly people are able to reach a decent wage,” Dube said.

Slowing the rise in worker pay is now a central focus of the Fed’s war against rising prices.

In the year since the Fed began raising interest rates, costs have eased for durable goods like used cars and furniture, while rent increases have shown signs of decelerating, but inflation is rising for services sectors where labor costs are often the biggest expense. In real-life terms — that is, not adjusted for inflation — average hourly earnings across private sector employees increased a robust 4.4 percent during the 12 months ending in April.

Fed officials’ fear is that rapid wage growth, while not the initial cause of inflation, could keep prices rising faster than they otherwise would have, rendering that higher pay mostly just empty calories. That has put the Fed in the awkward position of arguing that having people’s paychecks keep better pace with the increasing cost of living is bad for the overall economy.

“To be clear, strong wage growth is a good thing,” Powell, the Fed chief, has said. “But for wage growth to be sustainable, it needs to be consistent with 2 percent inflation.”

Powell is facing a steady onslaught of criticism from the left, most prominently Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), who has blasted rate hikes on the Senate floor, on Sunday morning news shows and in interviews. A progressive coalition is also mobilized around her argument that the central bank is limited in how much it can fight this bout of inflation, primarily caused by pandemic-related supply snarls, and so at a certain point, higher borrowing costs just scapegoats workers without clear benefit.

Another Massachusetts Democrat, Rep. Ayanna Pressley, argue that the Fed’s rate hikes were “reckless” and groups like progressive think tank Groundwork Collaborative warn that any impending recession and rise in unemployment is avoidable.

(get multi-billion dollar for gigantic streaming across the globe but pay too low salaries for writers?)

So far, that rise — while expected — is just a forecast. The job market has held up better than expected, with sky-high job vacancies and unemployment dipping to its lowest level in modern U.S. history, other than during the Korean War. Washington policymakers are bracing to see how long the labor market holds up in the face of the central bank’s inflation fight.

One big question heading into 2024 is how the economy will behave for Biden. Staff economists at the Fed have projected a mild recession sometime later this year, though they expect the recovery to be underway by sometime next year.

For its part, the Biden administration argues that it has gone to bat for workers in a manner that will sustain them in the long run, despite the Fed’s recent actions.

Heather Boushey, a member of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, said the president has aimed to pursue policies that ensure the economy can be more productive — investments in infrastructure and clean energy, for instance — to help keep up the wage gains for lower-earning workers.

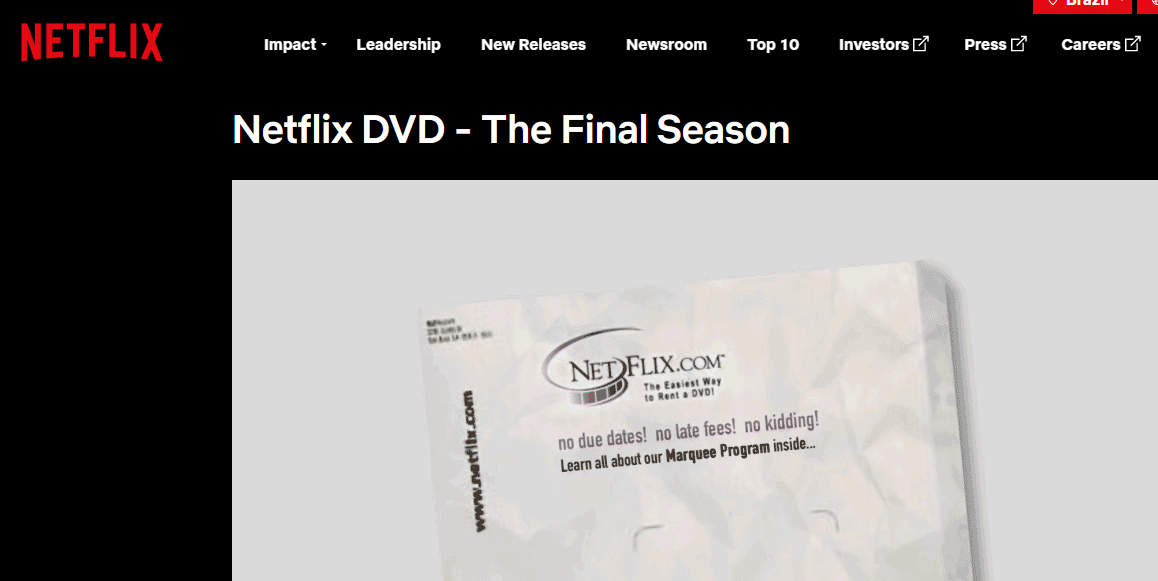

At the center of the Hollywood writers strike is this simple fact: Streaming is not meaningfully different from how people have always watched television and movies. You have some form of screen—a TV, laptop, tablet, whatever—and you choose something to watch. Though the specific mode of delivery has changed—the TV antenna became the cable box and then WiFi—and hard 22-minute time limits aside, the way people consume TV shows looks remarkably similar to how it has been for the past several decades.

Much depends, of course, on the Fed. Notably, Powell’s past commitment to workers is a big reason why he, a Trump-appointed Republican, was tapped by Biden for a second term. The Fed chief declared in 2020 that he and his fellow policymakers would focus more on workers by holding off on raising interest rates for as long as possible — defying decades of central bank policy in adopting a new, labor-centered framework.

Fed officials had learned, over the past several years, that the unemployment rate could drop lower than they thought without causing problems. In the years leading up to the pandemic, under Trump, the economic expansion became the longest in U.S. history, and joblessness dropped to 3.5 percent, its lowest level since the 1960s. And yet, inflation remained stubbornly below the Fed’s 2 percent target. That ratified a growing consensus that the central bank had often reacted too quickly to head off inflation that was never coming.

With those lessons in mind, the Fed didn’t begin raising interest rates until March 2022, roughly a year after inflation began to spike — initially in just a couple of sectors and eventually across the entire economy. The Fed’s decision not to counteract stimulus pumped into the economy by Congress and the Biden administration likely had twin effects: It allowed inflation to fester but also gave the labor market more time to heal.

If prices continue to cool without significant pain in the job market, workers at all income levels could see a generational boost to earnings. Even if wage growth slows, if price growth slows by more, that means more money in people’s pockets.

But if inflation stays stubbornly high, the Fed will feel compelled to take the hammer a bit harder to the labor market in a bid to further slow spending and investment, fueling more political outrage at Powell from the left. Though the central bank’s moves have hit wealthy Americans and businesses through losses in the stock market and higher borrowing costs, corporate profits have stayed high.

This is why, for a lot of entertainment writers on strike, the future of writing to them looks like a guarantee of something they know works and believe should continue working. Their argument is: Why are we trying to change a system that has produced some of the greatest TV of our lifetimes?

The future of writing, as the studio bosses see it, is Uber.

Hollywood has what I like to call “Silicon Valley Fever,” where older industries look at the tech boom and want the same kinds of returns the major tech stocks do, despite the fact that they already make—and will make, well into the future—mind-boggling amounts of money. But why have one pile of mind-boggling amounts of money when you could have two? They look at tech and its business model of three labor abuses in a trenchcoat and think: Yeah, I want a piece of that. If only those pesky unions weren’t around. And so they pretend that anything on the internet is somehow a brand-new innovation, rather than simply a new delivery method for the same old services.

With so many tech companies, leadership thought they were disrupting the whole industry—and ended up reinventing a thing that already existed. Uber has invented the bus five times. WeWork reinvented the co-op. And, at the end of the day, Theranos was running tests on existing blood-work machines. Many studios, especially Netflix, would like you to believe that they have reinvented TV and movies, except the truth is that they just don’t want to pay writers as much money for their work anymore. It’s the only way they can continue to show growth in profit. One billionaire’s “disruption” is thousands of workers’ crushed livelihoods.

(cinematic universe of JACK RYAN. James Cromwell in “The Sum of All Fears” —- part of Jack Ryan’s universe)

The strike is now in its fourth week after unionized film and TV writers voted overwhelmingly to strike following contract negotiations breaking down between their union, the Writers Guild of America, and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, a long and fancy name for the industry group that represents many of the studios during collective bargaining. The strike has already shut down all the late-night programs as well as shows that otherwise would be in production, including Abbott Elementary and Stranger Things. It shows no sign of ending anytime soon.

“They want to try new things, which in some ways I have respect for. But on the other hand, it's like the system exists because it works.” TV writer Angela Harvey, of Teen Wolf, and co-chair of the Think Tank for Inclusion and Equity, which advocates on behalf of historically excluded groups in the entertainment industry, said last year.

It’s a sentiment that has since been echoed by many striking writers. “They broke television. This is us fixing it,” one negotiating team member said. A board member summarized it as the WGA saving the studios “from themselves.”

The first stage of Silicon Valley Fever goes something like this: Take a service, make an app for it, and then claim that you’ve created a whole new industry by “disrupting” the existing one. If an app isn't sexy enough, claim your brand-new thing is whatever's popular at the moment: cryptocurrency, the blockchain, AI, whatever. The important thing to keep in mind is that "disruption” is code for operations that are unregulated and non-union.

Writers are the lifeblood of episodic television. Any kind of scripted episodic TV relies heavily on writers because everything is in constant flux. The writers help track continuity; they make sure a show gets where it was intended to go. If something changes that plan, they are the ones best positioned to help rewrite it. In doing all that writing and rewriting, the writers' room also served as an apprenticeship on how to make good TV: Writers learned what worked and also saw what they would have to do if they wanted to be, say, a producer or showrunner.

(Promoting to more engage in Substack) Seamless to listen to your favorite podcasts on Substack. You can buy a better headset to listen to a podcast here (GST DE352306207). Listeners on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Overcast, or Pocket Casts simultaneously. podcasting can transform more of a conversation. Invite listeners to weigh in on episodes directly with you and with each other through discussion threads. At Substack, the process is to build with writers. Podcasts are an amazing feature of the Substack. I wish it had a feature to read the words we have written down without us having to do the speaking.

That’s not the case anymore. Even the most powerful and famous showrunners have to fight tooth and nail to keep writers around during production. Writers can have several seasons under their belt without ever producing their own episodes—or without any guarantees of being back for the next season. They can find themselves with job titles that do not reflect anything they are actually doing, or comfortable doing. They can watch episodes with their name on it that bear no resemblance to the script they turned in.

(Michael Kelly also part of Jack Ryan’s universe like James Cromwell, but Kelly in JR series)

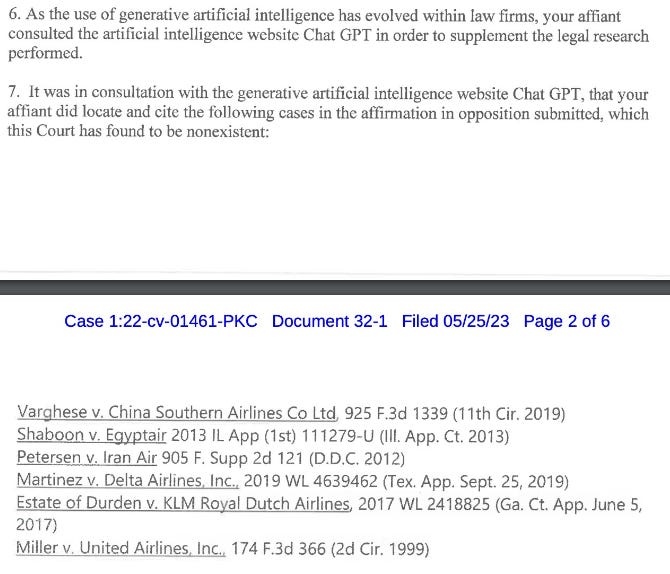

Meanwhile, the pay for writers is plummeting, especially in the form of compensation known as residuals—payments made to people who worked on a show that continues to be re-aired, the best example being reruns. Adam Conover, a WGA-West board member and negotiating team member, explained it to me this way in between picket lines.

“If you do what I did, which is you go make a show for the smallest channel on basic cable, and then you do the same show for Netflix, the executive producers there told me, ‘Hey, we can pay writers whatever we want. They have no minimums, they have no weekly guarantees, we can do whatever we want with writers’—those were their exact words," Conover said.

“I'm holding in my hands right now my first residual checks for The G Word, which came out in May of 2022,” he continued, referring to the show he did for Netflix. “So it's my first year of residuals, and they literally totaled $500 for the entire series for a full year. On TruTV, you know, the first year Adam Ruins Everything was on the air, I received a five-figure residual check, right? And I still get checks. You know, every year I get a couple thousand bucks from that show because they still run it on TruTV. And the writers for my show use that to pay their rent.”

Here's another breakdown of how this goes. Appendix A of the WGA’s minimum bargaining agreement (MBA) covers basically anything that isn’t fictional serial television or movies. Late night, daytime talk shows, soap operas, sketch comedy–all of it. When writers are writing for a traditional TV channel, they are covered by the MBA. When they are writing for streaming platforms, they have no protections. None of those rules apply. The residuals Conover and his writers received were whatever Netflix decided to give them.

It seems clear that Netflix should be held to the same rules as TruTV. If your company name is now a verb, you should pay your workers.

The second stage of Silicon Valley Fever: Grow your user base as big and as fast as possible, regardless of whether that growth makes sense or is sustainable. For Hollywood’s working writers, this desperation for corporate growth has furthered the studio’s attempts to turn writing from a career into a gig.

Getting on a show used to be a year’s worth of guaranteed work. Unless you were so bad you needed to be essentially fired, another season of a show meant another year of work. Not anymore. TV writing has become so erratic and hard to predict that writers will just pick up writing-room work when they can, which also means they might not get to return to their own show.

“The idea now is that nobody comes back because you bounced when the room ended, and you're three shows in before that show even premieres, because it’s become really hard to string together enough jobs to keep year-round employment,” TV writer Amanda Green, whose credits include Lethal Weapon and Manifest, said in 2022. “So if you don't have time in your schedule to get to come back for the second season, you don’t get the same opportunities for growth. You're just starting at square one every time.” So not only do the writers start from square one every season, but the show does too.

Staffing is wildly uneven. Many writers used to begin their careers as writers’ assistants or script supervisors or script coordinators, then they would move on to being staff writers, and then story editors, and later on executive story editors. Then they would move on to receive title of co-producer, then producer, supervising producer, executive producer and, maybe, eventually, showrunner. But the current economics of TV writing have made it so that rooms often end up either top-heavy—with overqualified people taking jobs to survive—or bottom-heavy with newer writers, requiring showrunners to take on even more work. As Harvey pointed out, there are almost no mid-level writers anymore. How can a staff writer see the path up when that middle is cut out?

“You'll hear, ‘Oh, this room had four upper-levels and a staff writer,’ or you'll hear, ‘This room had the showrunner and five staff writers.’” she said. “The people getting squished are in the middle. You'll never hear there was, like, three mid-levels.

“It's such a self-defeating phenomenon. Every level brings something different to the room, a different level of experience, a different level of insight, a different level of storytelling, a different style of storytelling. So when you cut all those pieces out, you're getting a lesser product in the end.”

During the strike, showrunners have pointed out how unsustainable it is to make a show with fewer than six writers. Plus, upper-level writers can’t engage in the mentorship the industry needs to be sustainable when they have to do everything else.

Rashad Raisani, whose writing credits include Burn Notice and 911: Lone Star, said that long before the strike, studios were taking advantage of how writing was much cheaper than production, banking scripts but not greenlighting shows, and forcing writers to figure out if they wanted to keep themselves available or go find another job.

“I think the real answer is dig a little deeper and fund these staffs and carry six writers. Carry them. There’s no reason why you can't. And if you guys are planning to hold something indefinitely that you've ordered, well, then that's your fucking problem,” Raisani said. “Why are you ordering something if you don't feel that confident? Let those writers go work on a show that's going to go if that's the case.”

Without writers around to help produce a show, you lose a lot. “And I've never seen an adverse reaction from viewers or fans that the writers' room did not predict," Green said. "It's just whether the writers' room cared, right?”

Today, it’s the inverse. Writers are getting blamed for things that they no longer control.

The third stage of Silicon Valley Fever is: ???????, which roughly translates to doing stuff until those at the top can complete the fourth and final stage: getting rich by either cashing out in a big sale or by gobbling up everything else. Both outcomes are inherently bad for consumers but, because this doesn't necessarily affect the heads of major studios, they do not see the decline of their product as a problem.

A number of studios aren’t in the hands of executives who understand and love television. NBCUniversal is owned by Comcast, an ISP and cable provider. Until recently, AT&T owned Warner Bros. and HBO. Amazon, Netflix, and Apple began as tech companies. Anyone who got into the business because they wanted to make TV might have no idea how to help the writers anymore. Shows with numbers that, under the old ratings metrics, would be no-brainers for renewal instead vanish: Lockwood & Co., for example, or the disappearing DC projects, on whatever the fuck the HBO app is currently named.

Take Netflix, which infamously tends to cancel a show after two seasons. It's based not on the show's popularity, but how much of those profits Netflix gets to keep, which goes down as production continues and costs go up. There are other considerations here: Does a five-season show get new subscribers in the same way as a new show? A lot of streaming relies on subscribers forgetting to cancel a subscription once the show they want is over. What's missing from all of this is whether the show is actually good.

“The issue with our whole economy is that it's all hedge funds and private equity that own everything. And they don't care about any single industry at all, let alone entertainment, they just want that bottom line, they want to grow on the bottom line every quarter, no matter what that takes, even if you're destroying your own business,” Harvey said. “Because they just think they'll go on to the next thing, but I don't think they realize they've hit the ceiling. There are no next things.”

Here is what the writers want: a guaranteed minimum writing staff size, a guaranteed ability to keep at least some writers through production, paying weekly rates across production, and guaranteeing a certain number of weeks of pay, and better residuals based on transparent reporting of viewing figures. So if the AMPTP had taken the WGA's offer, giving up less than five percent of its profits, the model that sustained profit in TV for decades would be adopted for streaming.

(A side note: the MBA is 755 pages long and basically acts as a living record of the history of writing in Hollywood. Conover explained that the WGA has too many things that are relevant every bargaining year, so they never waste time negotiating the removal of out-of-date things with the AMPTP. This is why the definition of “producer” includes the names of men who have mostly been dead for decades. It is like the Constitution. It is specifically like the Constitution of California, one of the longest in the world, because it is rarely subtracted from but is always being added to.)

The WGA estimated that the strike has already cost the studios more than they would have given up in taking the deal. Shockingly, anonymous studio execs told the trade publications that these numbers are wrong, but those anonymous sources did not provide their own numbers.

(I have no intel on this, but if the nontraditional tech execs aren’t the ones frothing at the mouth about this, I will eat my shirt. Tech policy is my day job, and those people hate explaining how they do anything. They want to be able to claim growth and also pretend the numbers justify what shows they keep and what they cancel. Forcing them to choose between inflating the numbers and not paying writers will make them apoplectic, I am sure.)

The sheer number of proposals that the AMPTP flat-out rejected is impressive. The number where the counteroffer was “meetings about the issue” was insulting. It’s particularly insulting when you read the MBA and see that the first page is a letter about how the WGA, in 1995, wanted writers to be eligible for a certain kind of credit, and settled instead for talks outside the MBA. They did not win that fight, and the writers remember how they were screwed before.

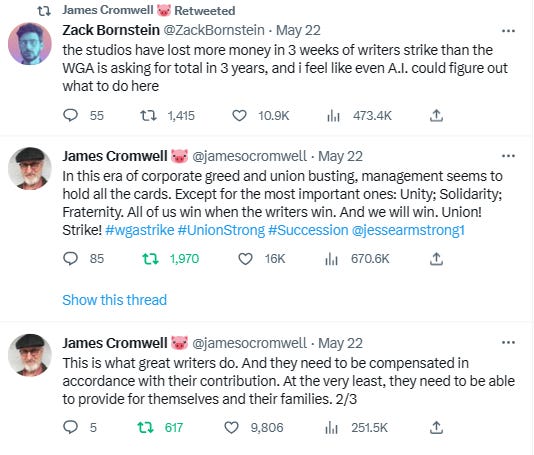

A version of this story could be written for any industry right now. You might even be able to write this about other Hollywood unions soon: The Directors Guild is also in negotiations with the AMPTP, while SAG-AFTRA, which represents performers, will begin negotiations of its own with AMPTP later on this year, with its members currently voting on a possible strike authorization.

This is what happens when the only metric that matters is growth. The problem is there are only so many humans on the planet and so many hours in the day. Even if Netflix somehow created a dystopia where every single human was watching Netflix 24 hours a day, what then? Do they weep like Alexander, with no more worlds left to conquer? What exactly is the problem with making, as Disney did last year, $28 billion every year for decades? Why is $28 billion in 2022, $32 billion in 2023, and nothing in 2024 better?

It’s not. It’s just better for whomever is in charge in 2023.

It is startling how often, before and after the strike began, writers referred to the gig economy as the future the AMPTP would consign them to. We are far past the point where gig work is seen as a flexible side job rather than exploitation of a vulnerable workforce. It is important not to see writers as greedy or think that they think they are above other workers. It is that they are lucky enough to already have a union and that beating back the terrible practices where they can is worth it.

“The things that we care about are the things the studios should care about,” Harvey said. “We care about people not being set up to fail. We care about better, authentic stories getting out there.”

The reality for writers is the same as it is for most other workers: Whatever chaos is going on at the executive level, the industry itself is profitable. It is stable. The people doing the work are getting work done against the odds. The constant corporate restructuring has not changed the work of the writers. The writers have delivered scripts, shows, and profits. They are saying, Whatever weird corporate flight of fancy you are on should not affect us.

I keep thinking of something Mike Schur, who co-created Parks and Recreation and created The Good Place, said to me years ago about making TV during COVID:

You know, if I were Jeff Bezos and I were worth $150 billion, I think I would have said, hey, effective immediately, I am spending $10 billion of my own money to retrofit all of our warehouses and to be safe. And I'm also bumping every employee salary with, you know, 30 percent hazard pay increases that will be permanent and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. But like, of course, he doesn't do that.

Like when I was at SNL, after 9/11, we all just looked at each other and we're like, how the hell are we writing dumb sketches? Like, how is that helping anyone? And other platitudes that people will say of, you know, Hey, people need to laugh and people need entertainment and this is how we get back to normal. And I found it to be extremely cold comfort at the time.

Ultimately you get to the point you're like, Well, this is my job. This is what I have to do. And there are people who rely on this industry for their paychecks and for food and shelter and clothing and happiness. And so, you know, I don't have any other choice. So you just sort of put your head down and do the best you can. This is our little tiny corner of the world, and so we're going to do this thing as well as we can and try to keep everybody who works on these shows as safe as it can be.

That’s ultimately what the strike is, on a larger scale: An attempt by writers to make their tiny corner of the workforce as safe and secure as it can be for the people in it. Or, as Conover said when I told him of Schur's words: “That's what a union does.”