Suppose that, during the year running from the summer of 1995 to the summer of 1996, American policy makers had increased federal spending by $250 billion (3 percent of the gross domestic product), cut short-term interest rates to below one-half of 1 percent, and flooded the economy with liquidity so that long-term interest rates were held below 3 percent while the dollar weakened by 30 percent, making our goods far cheaper in world markets. U.S. growth and employment would have boomed, and inflation would have jumped as the economy overheated.

These are precisely the steps that Japanese policy makers have taken since the summer of 1995 with little lasting positive impact on the Japanese economy. The payoff was a sharp, brief surge in growth to an annualized rate of 12.2 percent during the first quarter of 1996. Meanwhile, Japan’s stock market, hailed by American brokerage houses as the next major bull market, rose by more than a third, from 15,000 to a peak of 22,500 in June, before dropping back below 21,000 this fall.

Japan’s investors sold happily to American and European investors as they rushed to buy Tokyo market shares. When Japanese stocks threatened to fall, Japan’s national pension fund of more than 800 trillion yen ($8 trillion) bought Japanese shares in “price-keeping operations,” or PKOs, as they are affectionately known in Japan.

The Plunge

By summer, as America’s economy was turning in a 4.7 percent annual growth rate, which helped to reelect President William Clinton, Japan’s annual growth rate plunged to minus 3 percent, and the stock market slipped from its high of 22,500 to below 21,000 despite heavy support from continued record low interest rates (bond yields dropped as low as 2.4 percent) and an occasional PKO. Currently, estimates for third-quarter Japanese growth figures to be released in December are being revised downward to an average of zero or below. Next year looks no better.

The fact that Japanese investors had no interest in buying stocks turned Japan’s weaker yen policy–which had helped its exporters–into a liability for its stock market. Foreign investors, particularly American investors, who rushed to buy shares at the peak of the Tokyo stock market have lost 6 percent on share prices and another 10 percent from the weaker yen. This loss was happening while the U.S. stock market was up more than 22 percent on the year and the dollar had risen 10 percent against the yen.

U.S. investors, lured into Japan by J. P. Morgan, Morgan Stanley, and other U.S. brokerage houses, were losing a net 25 percent on Japanese equity holdings compared with U.S. equity holdings and another 10 percent on a weaker yen for every dollar they had moved from the United States to Japan.

Little wonder, then, that on November 7 in Tokyo (November 6 in the United States, one day after U.S. presidential elections) comments by the Japanese Finance Ministry’s “Mr. Yen,” Director General Eisuke Sakakibara, in Japan’s leading financial dailies confused global financial markets but were clearly directed at reversing the slide in Japan’s stock market. Sakakibara said: “The phase of the continuous correction of the yen’s appreciation is coming to an end, judging from economic fundamentals. . . . The ministry is no longer considering guiding the yen lower. . . . The recovery in Japanese stocks is more likely than that of an advance of U.S. stocks. . . . The newly constituted Hashimoto administration is serious about reforming the financial system and the finance ministry will not cling to regulations amid globalization of the financial sector.” Sakakibara suggested that private sector economists’ gloomy view on the Japanese economy was based on a “misplaced perception that the Hashimoto government would proceed conservatively on economic deregulation.”

Sakakibara’s desire to keep the Tokyo stock market from dropping below 20,000 was related, as are most of Japan’s ad hoc economic policy moves, to the desperately weak state of its financial sector. Japan’s generally insolvent banks are under pressure to meet Bank of International Settlements standards on capital adequacy. Accord-ing to Japan’s Nomura Research Institute, “As things now stand, the banks will have to cut their risk assets by 4 trillion yen (about 40 billion dollars) with the Nikkei average at the 20,000 level or by 20 trillion yen (about 200 billion dollars) if the stock average falls to 16,000 yen. Moreover, if these banks all issue preferred stocks or take profits on their equity holdings at the same time, the Nikkei average could plunge.”

The problems of Japan’s banks do not end with BIS standards. Again quoting the Nomura Research Institute: “To make matters worse, depositors disappointed by extremely low deposit rates and concerned about the shakiness of the financial system are shifting their money from time deposits to demand deposits. This in turn is forcing the banks to invest in liquid assets which is making it difficult for them to extend long term loans.”

Once more, in a sad pattern that has often been repeated since the collapse of Japan’s equity and property markets in 1990, ad hoc, manipulative measures have been taken by the Japanese government to try to stave off disaster in its financial sector. While Mr. Sakakibara’s comments evidently caused the dollar to fall by about 2.5 percent, his short-term perspective on equity markets was unfortunately contradicted. During the week after Mr. Sakakibara’s statement about the relative merits of U.S. and Japanese stock markets, the U.S. market rose by more than 4 percent, while the Japanese market actually fell by 0.3 percent.

Fatal Fundamentals?

Japan’s efforts to reinvigorate its economy and its stock market have so far foundered for fundamental reasons. Japanese policy makers have followed the advice of Keynesians while ignoring the wisdom of Keynes himself. Since 1992, 60 trillion yen ($600 billion) worth of public works spending, the ultimate Keynesian stimulus, has done no more than to recycle excessive private savings into Japan’s depleted spending stream. Meanwhile, the deflationary momentum, so much feared by Keynes and created by the lingering effects of the Bank of Japan’s overly tight monetary policy has not been broken. Until Japan’s consumers are convinced that goods will cost more next year rather than less, the economy will remain chronically depressed.

Japanese policy makers would do well to read portions of Keynes’s general theory related to the dangers of deflation and the symptoms of a liquidity trap. Japan’s deflationary problems began with its investment-led boom in the 1980s, which pushed stock prices and land prices to highly speculative levels. Rightly alarmed by runaway equity and land prices, the Bank of Japan pushed up interest rates in 1990 and 1991. Equity and land prices collapsed from their inflated levels. Subsequently, the Japanese government attempted to restimulate the economy with public works programs that did no more than substitute wasteful government investment in Japan’s inefficient domestic, nontraded goods sector for the excessive private investment that had driven the equity market to bubble levels before 1990.

Alarmed by the possible inflationary impact of growing fiscal stimulus packages, the Bank of Japan maintained a monetary policy that was too tight. Although after 1992 the Bank of Japan was lowering interest rates, until the middle of 1995 inflation was dropping faster than interest rates, so Japanese real interest rates were rising. The deflationary momentum was exacerbated by the sharp appreciation of the yen that resulted from Japan’s rising real interest rates and by the spreading insolvency of Japan’s financial sector. Meanwhile, growth of the Japanese economy stagnated for three years from 1993 to 1995.

The failure to recognize the extreme deflationary momentum that built up in Japan during 1994 and 1995 probably resulted from two problems. First, Japan’s inflation indexes are outmoded: they failed to measure falling prices in newer retail outlets that were taking business away from Japan’s traditional old, rigidly priced retail outlets. When the Bank of Japan undertook more representative samples of prices, analysts found that deflation was running at 3 percent per year and began to recognize the extreme dangers of a self-reinforcing deflation.

A second problem arose from the failure to recognize how deflation would operate on Japan’s savers and investors and thereby on Japan’s external accounts. As deflationary momentum in Japan accelerated, investment spending dried up rapidly, while high returns on financial assets including cash increased Japanese savings. As Japan’s net demand for foreign investment dried up, Japan’s net sales of goods to the rest of the world increased because the slowdown in Japan caused imports to collapse more rapidly than exports. The resulting excess demand for yen caused the Japanese currency to appreciate and accentuate the deflationary pressure in Japan.

Abetting Deflation

Japan’s deflationary pressure has been exacerbated by a classic Keynesian liquidity trap. Japan’s risk-averse households and corporations, made so by the collapse in equity and property markets, have found cash to be an attractive asset. Although cash pays no explicit interest rate, in a deflationary environment it rewards holders at a rate directly proportional to the deflation rate. Meanwhile, Japanese households have increased deflationary pressure by withdrawing funds from Japanese banks, thereby forcing a contraction in lending by the banks. For a Japanese household, the 0.2 percent offered by banks on time deposits does not compensate for the widely advertised risk that many Japanese financial institutions may be insolvent.

Deflationary momentum arises as households add to money balances rather than spend money or send it abroad. Less spending and more accumulation of financial assets at home lowers prices and causes the currency to appreciate, which lowers prices further. Japan had reached this deflationary crisis stage by the middle of 1995. The massive stimulus program in the form of another public works package equal to 3.0 percent of GDP, coupled with a sharp further easing of monetary policy by the Bank of Japan, has arrested the deflationary pressure in Japan but has not yet reversed it. Japan’s nervous households are still adding rapidly to cash balances. Japan’s narrowest measure, of money cash and demand deposits, is still rising at a 12 percent annual rate, although, as a slightly encouraging sign, this is down from the 16 percent rate of increase at the end of the summer.

The rapid increase in Japan’s narrow money is a classic symptom of a liquidity trap, where a rapid increase in the money supply does not bring about an increased demand for goods but simply reflects the public’s higher demand for money balances to hold in a deflationary environment. Broader money balances are stagnating or falling for two reasons. First, the public is withdrawing time and savings deposits from the banking system as interest rates on them drop toward zero. Second, the banks, needing to replenish reserves after heavy losses on property loans and equity holdings, cannot expand loans.

The much-hailed reduction in Japan’s current account surplus is not the result of a rapid increase in spending in Japan related to successful reflationary policies. Rather, it is the result of the relocation of Japanese production facilities offshore to avoid some of the negative costs of an overvalued yen and the high-priced domestic labor. As Japanese production is moved to other Asian locations or to the United States, recorded Japanese exports fall because shipments by Japanese companies to world markets from locations outside Japan are not counted as Japanese exports. Meanwhile, Japanese imports rise because Japanese production facilities outside Japan, such as Honda in the United States, are shipping Japanese products back to Japan and those products are counted as imports.

The yen has been depreciating since the spring of 1996 primarily because the extremely easy monetary policy of the Bank of Japan and the attendant flooding of the Japanese financial system with liquidity have increased the demand for foreign assets by some Japanese savers. With interest rates on long-term bonds driven below 2.5 percent and virtually no interest earnings on bank deposits, the sign that the Japanese yen’s chronic appreciation had been reversed and actually turned into depreciation caused some of Japan’s savers and financial institutions to invest in European and American bonds yielding from three to five percentage points above Japanese bonds. Simultaneously, as the Japanese yen began to weaken and the Japanese recovery that had been promised during the first half of 1996 waned, foreign capital inflows into Japan aimed at purchases of Japanese stocks were reduced. The increase in Japanese net outflows as the current account surplus fell caused the yen to depreciate.

It has become customary to attribute the yen’s depreciation to the desires of policy makers in Tokyo such as Eisuke Sakakibara. Yet he has done no more than favorably comment on the yen’s depreciation, attributable to fundamental factors: a sharp easing of monetary policy in Japan and a slowdown of foreign capital inflows to Japan for the purchase of the country’s financial assets. Forgotten are the comments by Mr. Sakakibara and other policy makers less than a year earlier that intervention could not change the fundamental direction of exchange markets but could only encourage movements already being generated by private market behavior.

Mr. Sakakibara’s weak yen policy has been tripped up by its possible negative impact on Japan’s stock market, which has been pushed up primarily by foreign purchases. Balancing the needs of the stock market with the needs of Japanese exporters to continue increasing sales to slowing world markets, Mr. Sakakibara seems to have suggested that he would like the yen to stay within a range of about 110-115 yen per dollar. Such latitude will be impossible to maintain if market fundamentals operate to push the exchange rate out of that range, Mr. Sakakibara’s comments notwithstanding.

Vital Steps

To sustain Japan’s much-needed economic recovery, Japan’s policy makers must do far more than attempt to jawbone the yen into a narrow range. After the sharp slowdown in growth in the second quarter of 1996, the second half of the year does not look promising, while 1997 looks even less so. As the large fiscal stimulus package initiated in September 1995 winds down, increased spending by Japanese households and businesses will be necessary to sustain the growth of aggregate demand in Japan’s economy. Low interest rates and some residual increases in incomes from the stimulus package may keep growth at about zero during the second half of 1996.

But, moving into 1997, Japan’s policy makers have created more problems. Japan’s new finance minister, Hiroshi Mitsuzuka, has indicated that in December the temporary income tax cut initiated as part of the stimulus package will be rescinded. On April 1, 1997, the start of Japan’s fiscal year, the national consumption tax will be increased from 3 percent to 5 percent. During the six months leading up to that increase, there may be some boost in spending by consumers attempting to avoid the higher tax, but that spree will only subtract from spending after April 1997. Part of the positive spending impact of the upcoming consumption tax increase has already occurred. For Japanese buying homes, contracts had to be signed by September 30, 1996, to avoid the increase in the consumption tax. As a result, home purchases and construction spending rose rapidly before September but will probably drop off thereafter, contributing to economic weakness in the second half of 1996.

Japan’s policy makers, by virtue of the ineffective outlay of $600 billion on public works projects over the past four years, have deprived themselves of higher government spending as a means to push the economy into a period of sustained growth. This outcome is probably good. Japanese companies need an attractive environment inside the country in which to produce for Japanese markets and world markets. That condition will require easing burdensome regulations, allowing the considerable initiative in Japan’s private sector to improve the efficiency of its distribution system and allowing Japan’s companies to adjust their labor costs downward by eliminating a large quantity of redundant labor, which is a key reason for the weakness of Japan’s stock market.

The redundant labor in Japan’s firms should be encouraged to move into new companies aimed at making Japan’s domestic economy more efficient. In short, Japanese companies must experience the same painful downsizing that American companies have undertaken over the past ten years and that some European companies are now initiating. The results will be less painful than supposed provided that lifting regulatory burdens opens opportunities for new companies.

Japan should probably consider a change in tax policy to encourage increased work effort, while not discouraging consumption by Japan’s high savers. Japan could optimize its fairly neutral tax system with a moderate effort and should do so as soon as possible.

The biggest need in Japan is to create attractive investment opportunities rather than try to simulate them with government public works programs. Many appealing opportunities could be created by eliminating Japan’s obsolete and burdensome system of regulation. To its credit, the new Hashimoto government is already proposing deregulation of the financial sector, but those measures need to go further and include permission for private sector workouts of the bad loans currently held by Japan’s banks and financial institutions.

Japanese consumers should be able to buy well-priced consumer goods in their own markets rather than being forced to swarm into name-brand shops in Paris, New York, London, and Rome to buy such goods. The transformation of the Japanese economy away from its still-mercantile stance toward a first-class global economy that replicates the high level of efficiency of its traded goods companies, such as Toyota and Sony, would cause an investment boom in Japan that even Japan’s savers might not be able to finance alone. The result would be a need for net capital inflows to Japan and even a Japanese current account deficit that mirrored net capital inflows to Japan.

Japanese policy makers might contemplate that, over the past year, while they were undertaking extraordinary fiscal and monetary stimulus measures, the United States was reducing its budget deficit from more than 2 percent of GDP down to 1.4 percent and the U.S. dollar was appreciating by more than 10 percent against the yen. So far in 1996, the U.S. stock market has risen by 25 percent, while the U.S. economy has grown steadily at about a 2.5 percent rate. Meanwhile, Japan’s stock market has stagnated, while 1996 growth is expected to be about 3 percent. The difference is represented by contrasting stock market performance: America’s growth is expected to continue while Japanese growth slows next year to about 1 percent.

Some analysts have tried to use Japan’s falling current account surplus as a guide to the prospective level of yen-dollar (or other) exchange rates. This analysis is misguided. A current account deficit is more a sign of strength than it is of weakness when it is generated because investment opportunities outrun domestic savings. A sweeping elimination of burdensome government regulations accompanied by a meaningful restructuring of Japan’s economy would sharply increase investment opportunities inside the nation. Meanwhile, the attendant increase in incomes and optimism might even cause Japan’s consumers to spend enough to create a current account deficit in Japan mirrored by net capital inflows. That change would be a healthy sign. Even more healthy would be a recognition by policy makers that a sound Japanese economy may, for a time, mean a current account deficit.

Japan has probably taken the first step toward economic recovery by demonstrating to itself, at immense cost, that massive Keynesian public works projects can produce only temporary, faster demand growth, not sustainable supply growth. Japan now needs to arrest deflationary momentum, repair its crippled financial sector, and undertake sweeping, rapid deregulation to create investment opportunities and thereby launch Japan back onto a self-sustaining growth path. Meanwhile, given the drag of higher taxes in the pipeline, a continued weakening of the yen to 130 yen per dollar, or weaker depending on the pace of deregulation, will be required to sustain Japan’s struggling economic recovery.

Investors need to be offered sound fundamental reasons to buy shares of Japanese companies that are transforming themselves into world-class producers. Those sound fundamentals–and not Mr. Yen’s oddly counterproductive effort to talk up the yen as if such a transformation had already been achieved–will cause Japan’s stock market to recover along with its economy.

——

-prada- (Adi Mulia Pradana) is a Helper. Former adviser (President Indonesia) Jokowi for mapping 2-times election. I used to get paid to catch all these blunders—now I do it for free. Trying to work out what's going on, what happens next. Arch enemies of the tobacco industry, (still) survive after getting doxed.

(Very rare compliment and initiative pledge. Thank you. Yes, even a lot of people associated me PRAVDA, not part of MIUCCIA PRADA. I’m literally asshole on debate, since in college). Especially tonight heated between Putin and Prigozhin.

========

Thanks for reading Prada’s Newsletter. I was lured, inspired by someone writer, his post in LinkedIn months ago, “Currently after a routine daily writing newsletter in the last 10 years, my subscriber reaches 100,000. Maybe one of my subscribers is your boss.” After I get followed / subscribed by (literally) prominent AI and prominent Chief Product and Technology of mammoth global media (both: Sir, thank you so much), I try crafting more / better writing.

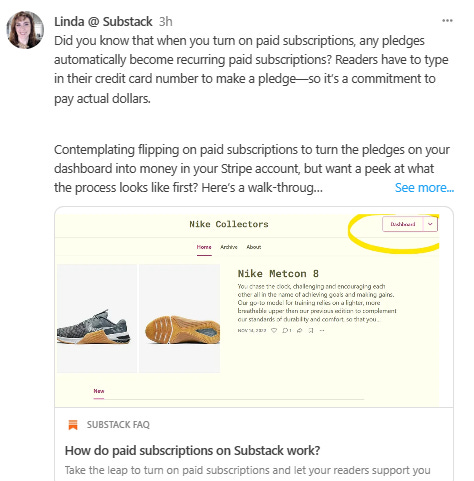

To get the ones who really appreciate your writing, and now prominent people appreciate my writing, priceless feeling. Prada ungated/no paywall every notes-but thank you for anyone open initiative pledge to me.

(Promoting to more engage in Substack) Seamless to listen to your favorite podcasts on Substack. You can buy a better headset to listen to a podcast here (GST DE352306207). Listeners on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Overcast, or Pocket Casts simultaneously. podcasting can transform more of a conversation. Invite listeners to weigh in on episodes directly with you and with each other through discussion threads. At Substack, the process is to build with writers. Podcasts are an amazing feature of the Substack. I wish it had a feature to read the words we have written down without us having to do the speaking. Thanks for reading Prada’s Newsletter.