UPDATE September 22, 2023 —- 9.48am Calgary

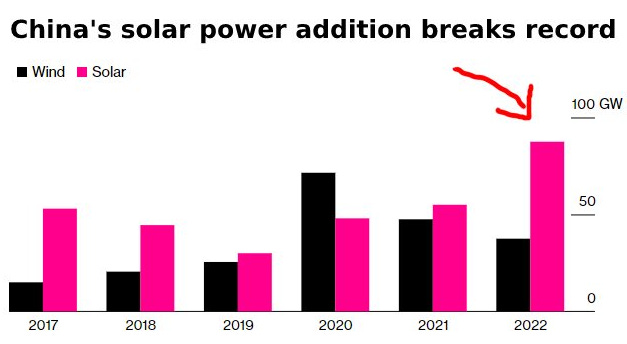

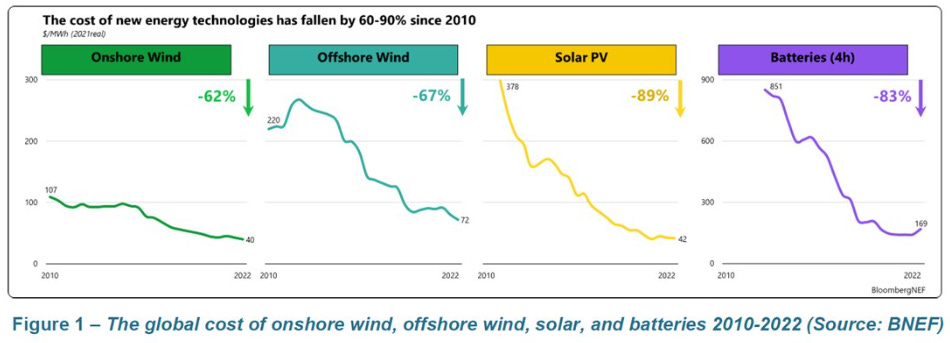

Even as oil prices threaten to break the US$100-per-barrel mark, it was the global transition to cleaner energy that was the focus of World Petroleum Congress in Calgary.

======

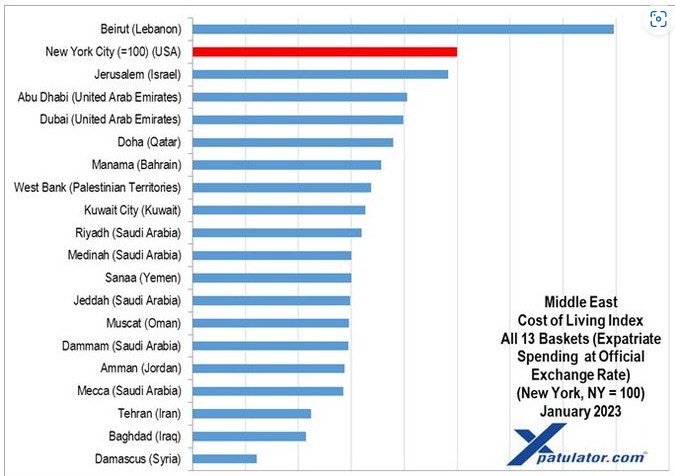

The new bankers to the world aren't on Wall Street. When Credit Suisse Group, BlackRock, hundreds of Russian Oligarchs, and Asia’s richest men were hunting for funds in recent months, they all turned to the same place — the Middle East. Nowhere are the intricacies of Middle Eastern dealmaking more on show than at the Saudi’s PIF. Saudi Arabia is open to discussions about trade in currencies other than the US dollar. Since December 2022 when MBS (Mohammed bin Salman) meet Chinese President Xi Jinping, China's calls for oil trade in Renmimbi Yuan at Gulf Summit in Riyadh.

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s blueprint to prepare the biggest Arab economy for the post-oil era. Authorities are already relaxing rules on entertainment, and by 2030, they aim to double household spending on recreation to 6 percent. Concerts, dance shows and even film screenings have drawn thousands of people over the past year.

The idea of creating separate areas for foreigners with looser rules also isn’t entirely new to Saudi Arabia. The most famous, the Saudi Aramco compound in Dhahran, is designed like an American suburb. On the gender-mixed campus of King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, attended by Saudis, women can drive and wear what they want.

And while alcohol is illegal, with authorities often busting homemade distilleries and distributors, it’s quietly consumed in many private homes and compounds dominated by wealthy expatriates.

With a target of managing $2-2.5 trillion of assets by 2025, officials are obligated to find deals that fit with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman's strategy for the kingdom. Saudi Arabia launches the Event Investment Fund, focused on supporting the sports, culture, tourism, and entertainment industries. India and Saudi Arabia overtook the UK as well. UBS in Dubai is hiring a group of private bankers from rival Credit Suisse as the Swiss lender continues to expand its Gulf business that caters to India’s wealthy diaspora. Saudi Arabian stocks benefited this year as Brent crude reached a peak of nearly $140.

Saudi Arabia, like many other Muslim-majority countries, does not allow men and women to live together unless they are “mahram” — an Arabic term referring to close family members or spouses.

(But) Saudi Arabia wants to turn hundreds of kilometers of its Red Sea coastline into a global tourism destination governed by laws “on par with international standards” as part of its plan to transform the economy and reduce its reliance on oil. Bringing sun-seekers to Saudi beaches could transform a tourism industry that relies almost solely on Muslim pilgrims visiting holy shrines in Mecca and Medina. But while the announcement emphasized the economic benefits, past mega-projects to diversify the economy have struggled to get off the ground, and questions are likely to be raised over how acceptable the plan is to the kingdom’s influential religious establishment.

The Mammoth - Lavish airports. First, Red Sea Airport, in Umluj Tabuk. The new Red Sea Airport has been inspired by the forms of the desert, the green oasis and the sea, removing the usual hassle associated with travel by providing a tranquil and memorable experience for passengers from the moment they arrive.

The design of the terminal aims to bring the experience of a private aircraft terminal to every traveller by providing smaller, intimate spaces that feel luxurious and personalised. The form of the roof shells cantilevers on the landside and airside to provide shade to the passengers. An internal green oasis with an indigenously planted garden forms a green focus, creating a relaxed, resort-like atmosphere within the airport terminal. The airport will be powered by 100 percent renewable energy.

The arrival experience is about speed of processing passengers, while welcoming them to their destination along with giving them a first impression of the Red Sea Experience. Upon arrival, passengers follow the natural spatial flow down through the lush oasis landscape towards the Welcome Centre, where they are met and welcomed to the Red Sea Resort. All security and immigration checks are dealt with speedily and the checked-in baggage is sent to the resorts directly. The centre offers an immersive experience of the highlights at the resort, giving visitors a flavour of what is to come.

The departure sequence is generally longer than the arrival experience, so the spaces are designed for longer waiting times with larger, more relaxed spaces. The five departure suites are arranged as a series of pods to allow an easy transition from their cars to the plane. Passengers are dropped off outside the terminal and quickly enter one of the departure pods which feature spas and restaurants enveloped in a relaxed atmosphere. The baggage is loaded onto the aircraft directly after being checked-in at the resort.

British architecture studio Foster + Partners is designing the six-runway King Salman International Airport in Riyadh, which is set to become one of the world's largest airports.

Named after Saudi Arabia's king Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, the King Salman International Airport will be designed by Foster + Partners and incorporate the existing terminals named after former king Khalid bin Abdulaziz Al Saud.

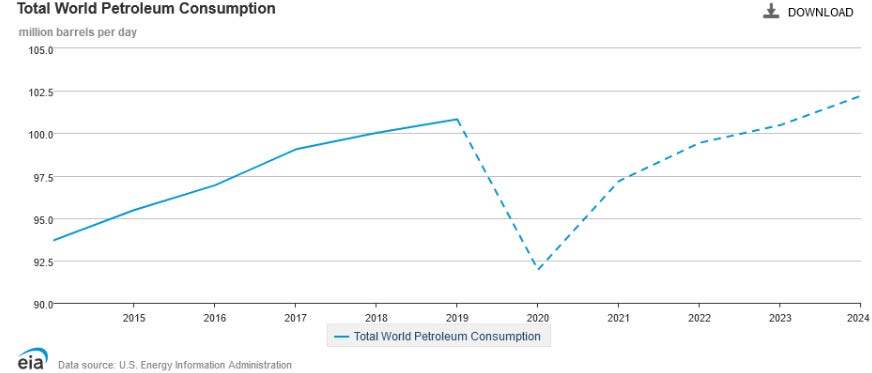

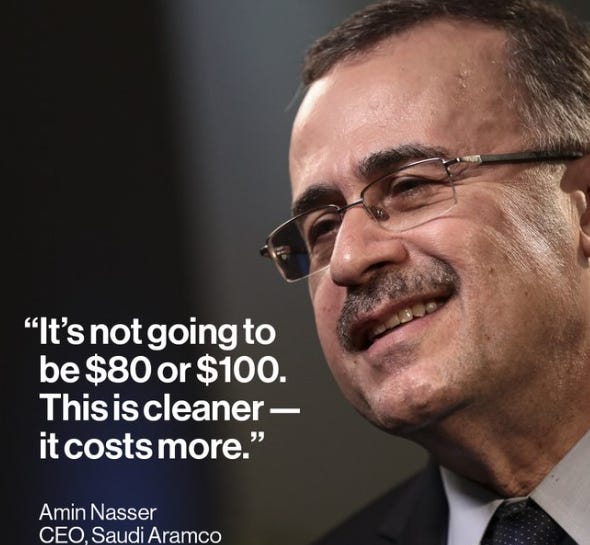

Blue hydrogen may end up costing the equivalent of around $250 a barrel of oil, though Saudi Aramco won’t know until it’s done more research, CEO Amin Nasser says. Amin continued, windfall tax is not helpful if policymakers want companies to invest. Amin also warns of possible oil supply shortages, as Chinese demand is set to surge. ARAMCO is looking at “close to” 300 active rigs by the end of this year. Aramco pleaded that the world needs additional investment elsewhere to meet global demand. The oil market’s rollercoaster volatility hasn’t been for the faint of heart, but it’s handing multibillion-dollar signing bonuses to some of the traders who can stomach it.

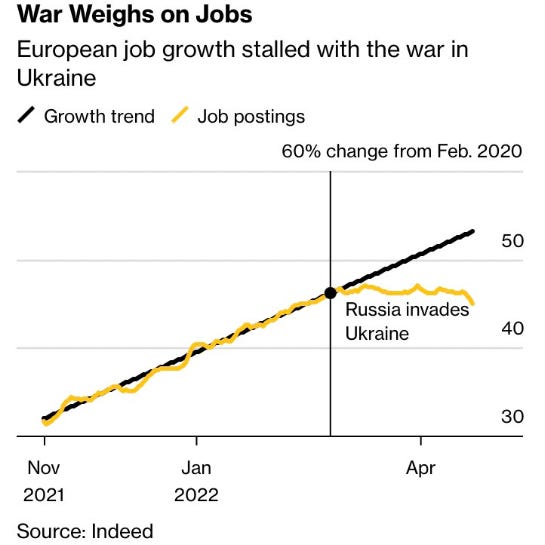

Cheap energy isn't coming back this decade. Oil forecasters see the market becoming more stretched, but the degree and nature of that shift is up for debate. It’s not just Covid-19 that the oil market should worry about. Rising tariffs on trade, Brexit - even with a trade deal, IRA dispute EU v U.S., - and the possibility Biden will be hobbled by a hostile House (55th House Speaker Kevin Owen Mc Carthy) especially about $31.4 Trillion debt-ceiling, may all slow the economic recovery in 2023. Brussels (European Union) is coming under pressure from European business to respond to the US’s IRA multi-billion dollar clean energy subsidy plan. EU should fast-track investments in clean tech and boost funding for the energy transition in response to a US climate law, Ursula von der Leyen says.

After 2 months of Price Cap, part of sanction to Russia, Oil Cap Costs Russia $170 Million a Day. Putin insisted Russia’s economy beat expectations. U.S. and Europe are quick to remind anybody who will listen that Russia is turning energy into a geopolitical weapon. But outrage aside, nobody should be shocked Russia is using this playbook. Russia exited 2022 pumping 11.2m b/d in total oil liquids, down just 1.6% (or 190k b/d) from pre-invasion levels. And the IEA (international Energy Agency) has once again lifted its short-term view for Russia. For example, last month it said output would drop to ~10.5m barrel/day (b/d) in January. Now, it sees >11m b/d.

China purchased $60 billion in Russian energy since the Ukraine War began until Week 1st November 2022. In 2021, China purchased $35 billion in Russian energy during the same time frame. After Elliott storm in last Christmas 2022, and deluge - storm across California non-stop since Jan 4th until today, Biden is considering requiring oil companies to store more fuel inside the US as dwindling diesel stockpiles stoke concerns about price spikes.

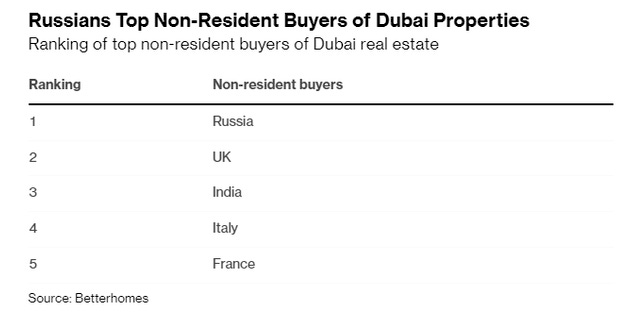

Russia has been showered with sanctions and export controls that seek to cut them off from the global economy, using a kind of systematic might to hinder the Kremlin’s war efforts and punish Putin’s allies. Russian buyers help to propel Dubai UAE and Tashkent Uzbekistan, Istanbul + Ankara Turkiye property sales to record. Putin’s weaponization of energy is a risky game for Russia, writes. But for now, at least, Putin is getting a little comic relief as he watches European governments throw money at the problem he has made.

But in the real world, has it actually worked? Far away from the parties in Davos, Putin on Tuesday (Jan 17th) used new government data to paint a surprisingly rosy picture of Russia’s economy. “The actual dynamics of the economy turned out to be better than many expert forecasts,” he said, staring at the screen during a virtual meeting on the economy. The disputes over energy attest, conflicting national interests can be a powerful force.

Citing data from the Ministry of Economic Development, Putin said that the gross domestic product of Russia had declined between January and November 2022 — but only by 2.1 percent. He noted that “some of our experts, not to mention foreign experts, predicted a decline of 10 percent, 15 percent and even 20 percent.”

Initial calculations suggested that Russia’s economy had shrunk by 2.5 percent over the entire 2022, the Russian president said — significantly better than the 33 percent contraction in Ukraine’s economy last year. “Our task is to support and consolidate this positive trend,” Putin added. In St Petersburg today to commemorate Russian heroes in the past, Putin assured Russia will win in Ukraine's battlefield, no matter how gargantuan help by NATO to Zelensky. NATO, G7 (*of course include Japan), U.S., the West should spend a little more time and energy devising potential off-ramps and less on dreaming up ways to fuel a war that serves nobody’s interests.

The scale of economic firepower directed at Russia since Feb. 24 2022 has been unprecedented for a large country, with the country’s banks banned from the Belgium-based SWIFT messaging system used in international transactions and sanctions on its central bank.

But Russian data does seem to suggest that the scale of the impact was less severe than many expected. Though Putin may not be at Davos, Russia is not completely cut off from the world either. The country’s current account balance — effectively a record of its trade with the rest of the world — surged over the past year in a way that would have implied a boom year in any normal time.

“Russia is still an energy power but its role has dramatically changed,” Vladimir Milov, former Russian deputy energy minister now living abroad, recently told the Wall Street Journal. “Russia will have a smaller market share in oil and gas, it will make less profit and it has lost some of its geopolitical leverage as well.”

That means less income for the Russian state going forward, even as its expenditure surges due to the invasion of Ukraine. Moscow posted a budget deficit of roughly $47.3 billion in 2022, according to official announcements — at roughly 2.3 percent of GDP, that’s one of the worst financial years in the country’s history.

Yes, that’s a lower deficit than the United States. But Russia doesn’t have a globally sought currency like the U.S. dollar, so it can’t just print more money without consequences. As its own sanctions on U.S. citizens have shown, Russia doesn’t have a ton of leverage in the worldwide economy — other than the diminishing power afforded by oil and gas.

In the long view, things don’t look rosy for Russia’s economy. Putin is correct that many predicted things would be far worse in 2022 — some economists told Today’s WorldView in March that they feared Russia’s economy could collapse, causing misery to ordinary civilians far outside Kremlin walls and unknown global consequences.

Saudi Arabia signals a shift in how it offers financial help to countries, making future aid conditional on promises to revamp their economies. Aramco acquires the trading arm of US refiner Motiva as the state-owned oil giant expands its operations in the Americas. A key oil gauge again flashes oversupply signals despite US crude inventories tightening, in the latest sign that the futures market is trading out of sync with typical physical cues.

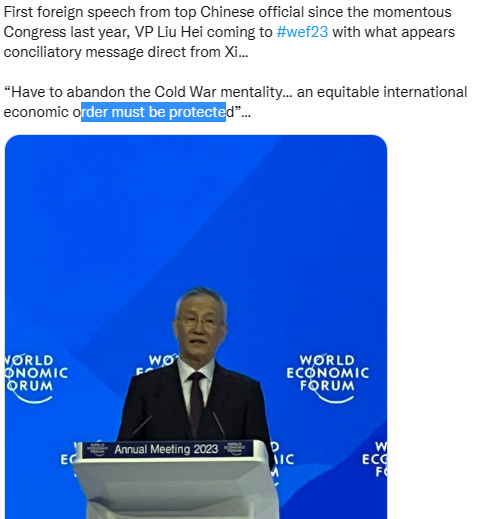

The spending habits of the Gulf's wealth funds, private equity predictions and BMO gets Fed blessing for biggest buy. Aramco is also very confident demand will pick up strongly this year as China reopens its economy and the aviation market recovers and boost tourism across the world. Oil pushed higher on optimism that energy demand in China will improve this year after officials ditched Covid Zero. Chinese official Vice Premier Liu He (meeting with Treasury Janet Yellen) told the Davos gathering that the world’s second largest economy is returning to normal, reassured no conflict between U.S. and China. The number of oil futures contracts held by traders rises to a six-month high, buoyed by optimism that China’s reopening will spur demand for raw materials.

Surging energy prices left funds from Saudi Arabia to Qatar and Abu Dhabi managing more than $4 trillion. They’re now bankrolling some of the world’s biggest rescue packages, investments and acquisitions — and show no signs of pulling back in 2023. Middle East wealth funds spent more than $88.9 billion on investments in 2022, double the previous year, according to data provider Global SWF, with deal makers using their wealth to diversify their economies and win geopolitical influence. An outsized $51.6 billion of that amount went into Europe and North America. Yet vast pools of Middle Eastern capital remain untapped. Officials at Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund are under intense pressure to deploy money, while the Qatar Investment Authority is on the hunt for more overseas deals, sources say.

In previous years, Gulf funds had a reputation for snapping up trophy assets. Now, they are being more tactical — using their wealth to claim a bigger role on the world stage, diversify their economies and win geopolitical influence. In the UK, not only land or mansion, as a target “ultra rich” sultanate(s), emir(s) from the Middle East. After Manchester City and Newcastle United, in the next 6 months from now, maybe the new owners of Manchester United and Liverpool will be from the Middle East. Middle Eastern investors are now harder to win over and quick to reject deals that don’t fit with their goals of nation building or generating returns.

Geopolitical factors are also at play. Some European governments have become more cautious about their trading relationships with China, giving the Middle East more opportunities. Germany has already secured a long term deal of energy with Qatar, the next maybe Iraq. With better income from exporting energy, Iraq is hosting the Arabian Gulf Cup soccer tournament for the first time since 1979, seeking to turn the page on decades of violence, instability and isolation.

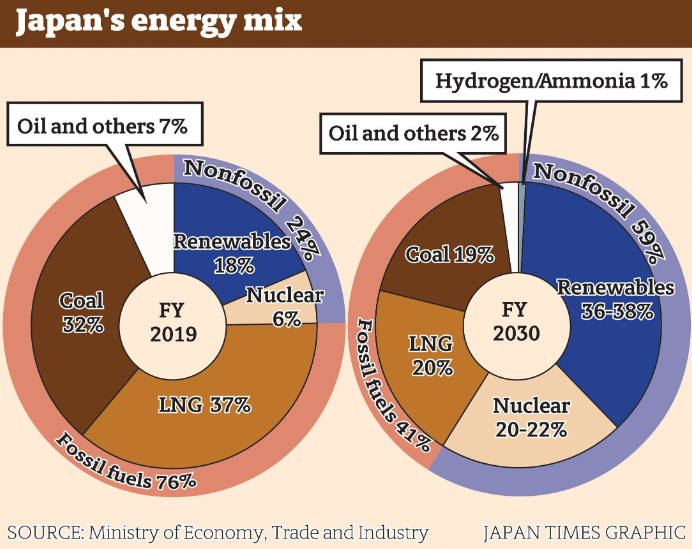

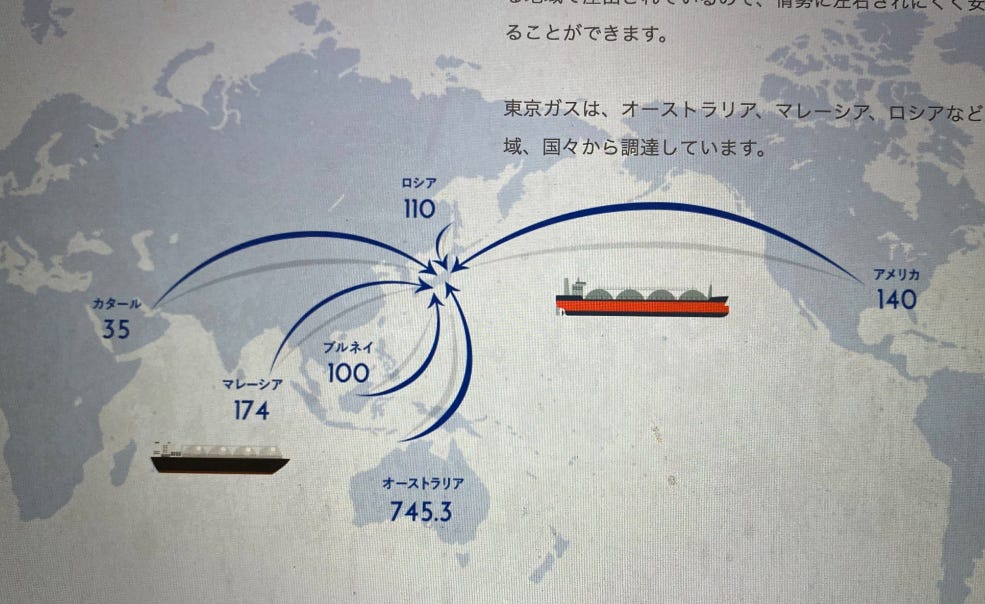

Japan has already secured a long term deal of energy with Oman, so Japan have at least 2 supplies: Indonesia Blok Tangguh and Oman. Following Japan, Thailand signs long-term deal to buy LNG from Oman in move to boost energy security. Buyers rush to secure supply from Oman, since few exporters have anything available before 2026. Japan and UAE sign agreements to support the transition to clean energy and boost bilateral cooperation. Japan imported its 1st shipment of liquefied natural gas more than 50 years ago today. Now the nation is the world’s largest buyer of the fuel (and pioneered the industry), becoming an LNG juggernaut. Importing LNG was Japan’s energy future. But he knew that in order for it to be profitable, they needed to import much larger volumes. Today, LNG dominates Japan’s energy mix. When you heat your stove or warm up the bath, you’re most likely using gas that has been liquefied and transported across the ocean from nations including Qatar, Australia, Indonesia and the US. Japanese companies investing in LNG facilities or signing long-term deals underpinned countless export projects over the last 5 decades. Without Japan’s enormous demand for LNG, the industry would not be where it is today. Germany (after built 1st ever LNG refinery 6 weeks ago) try to reduplicate Japan success story in LNG, to overhaul entire supply-reliance from Nord Stream Russia.

But feeling worried about the Middle East also emerged. European Parliament will build “firewalls” to prevent cases of corruption after allegations of bribes to lawmakers related to Qatar and Morocco, after Qatargate. Read immediately worsens situation between EU and Qatar, UAE official says European ties with Gulf 'should not be transactional.'

In Abqaiq, the biggest oil processing facility on the planet, there is no sense the world may be coming to the end of the oil era. The complex, about 25 miles from the coastline of the Persian Gulf, is the size of about 350 football pitches. In one of three control rooms, a dozen Saudi Aramco staff sit behind computer screens monitoring a system that can process as much as 7mn barrels of oil per day, representing one in every 14 barrels sold worldwide. The crude is depressurised in silver, dome-shaped “spheroids” and then piped into 18 stabiliser columns, where impurities like dissolved gases and hydrogen sulphide are removed, before it is sent for refining.

As the case against use of fossil fuels hardens, several of the biggest western oil companies have in the past five years reconsidered their commitment to the crude oil that has been the bedrock of the global economy for over a hundred years. Aramco is doing the opposite: it is doubling down. The state-owned giant that already produces about 10 per cent of the world’s oil is boosting its maximum production capacity from 12mn barrels a day to 13mn b/d by 2027 and aiming to increase its gas production by more than 50 per cent by 2030. Aramco has also invested in petrochemicals production and hydrogen projects. Ultimately, the world’s biggest crude producer is betting that it can continue to do what it does best: pump oil for decades to come and gain even more market power as other producers cut back.

Ahmad al-Khowaiter, a second-generation Aramco employee educated at the University of California and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is a key figure in the company’s drive for “sustainability”. The energy group’s pitch is that it can provide the “lowest carbon” barrel of oil in the industry and that as long as the world needs to use oil, that oil should be Aramco’s. In the company’s first ever sustainability report, published in June, the phrases “lowest carbon” and “least carbon” appear at least 14 times in the first 33 pages. “As you know, we are the world’s lowest emitter of greenhouse gas per barrel of oil among major producers, around 10.7kg [of CO₂ equivalent per barrel of oil equivalent],” continues al-Khowaiter.

Aramco increasing its oil production and market share is therefore “better for the world”, he argues. “You really want the lowest carbon emitter to take a larger market share, because that will bring down the overall carbon footprint of the oil industry.” But the question of whether cutting operational emissions has any real climate impact if the world is still burning millions of barrels of Aramco’s oil a day is a subject of fraught debate.

On average, roughly 85 per cent of the emissions linked to a barrel of oil is produced when it is burnt, and only 15 per cent during its production. “You can’t decarbonise oil because of the fundamental end-use emissions,” says Michael Coffin, a former BP geologist who is now the head of oil, gas and mining at the think-tank Carbon Tracker. “It’s a myth.” Carbon credentials Ever proud of its contribution to the development of modern Saudi Arabia, Aramco straddles the old and the new.

The corridors of its headquarters are lined with black and white photos of the past, while a generation of bright, young Saudis work on the latest technologies in adjacent rooms. Founded in 1933 as a partnership with Standard Oil of the US, Aramco produced its first oil in 1938. The Saudi Arabian government acquired 25 per cent of the company in 1973 and had taken full control by 1980. Aramco’s rivals such as US supermajor ExxonMobil and Europe’s Shell have global portfolios of oil and gas assets, which they can reshuffle as political and commercial priorities change.

Aramco’s oilfields, in contrast, are all in Saudi Arabia, where they remain central to the government’s economic plans. The company has produced more than 145bn barrels of oil since it drilled that first successful well more than 80 years ago, and it claims to have at least 253bn barrels of proven reserves available in the kingdom — enough to meet total global demand for about seven years. In a marked shift, in October 2021 Saudi Arabia pledged to lower its emissions to net zero by 2060 through investments in renewable energy and carbon capture technology to reduce the emissions from its oilfields. However, the government has no plans to lower production of hydrocarbons. In fact, shifting domestic power generation to renewable sources will have the added advantages of freeing up more oil for export and thereby generating additional revenue for the kingdom, according to energy minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman. “It’s a triple-win situation,”

Clean energy investments are part of an ambitious plan by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman to modernise the conservative country. But to fund each megaproject the kingdom’s day-to-day leader needs the petrodollars to continue to flow, even as he seeks to diversify the economy.

As a result, Aramco is even more focused than its rivals on maximising the longevity of its fields. In 2021, Aramco had 864 patents granted by the US Patent Office, most of which related to innovations in “subsurface” technology designed to improve the efficiency of its oil production and prolong the life of its fields, says al-Khowaiter. This is between two and three times more patents than the next international oil company, he estimates.

The high number of patents also reflects Aramco’s involvement in all phases of the hydrocarbon supply chain from exploration to refining and distribution — a characteristic Aramco says will be an advantage as the emissions-reporting demands from regulators and customers increase. “You’ll see our ability to track every drop of oil, every cubic foot of gas from its source to at least the Saudi point of sale,” says Ahmad al-Khowaiter.

In comparison, in parts of the US oil and gas industry, for example, different companies are involved in production, transportation and liquefaction, he says. “That gives us an advantage because we can commit with very high accuracy to the carbon footprints that we provide for our products.” Some of the efforts to reduce operational emissions across Aramco’s operations are easy to spot. Drones are used at Abqaiq to check equipment for leaks of methane, a greenhouse gas that is the second biggest contributor to climate change after carbon dioxide.

At the Hawiyah natural gas liquids recovery plant, 150km further south, the kingdom’s first carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) project collects carbon dioxide and re-uses it for enhanced oil recovery in part of the neighbouring Ghawar oilfield, the largest in the world. Ramping up the use of CCS technology is central to Aramco’s strategy. The Hawiyah facility, which opened in 2015, can currently capture about 800,000 tonnes of CO₂ a year. Aramco aims to capture 11mn tonnes across its facilities by 2035, which could then be used for chemicals, plastics and polymer production, it says.

Ultimately Aramco argues that its “lower carbon” barrels will command a higher price in the future than rival barrels with higher associated emissions. “If you have to offset the emissions associated with that oil, that’s a lower offset cost, so there’s economics behind it as well,” says al-Khowaiter. “We believe that as we . . . create products that are even lower emissions with offset carbon credits, it will become even more attractive.”

Some experts agree with al-Khowaiter’s argument. “Bar any political obstacles Saudi Aramco will be the last oil producer standing,” says Valérie Marcel, an expert in national oil companies at Chatham House. “They have the lowest costs and now they have the lowest emissions. It obviously is a barrel of oil that has a more rightful place in international markets.” However, despite the company’s commitment to reduce the carbon produced by its operations, the absolute emissions from Aramco’s wholly owned assets will barely change between now and 2035, according to its own sustainability report.

Aramco’s operations and the energy they consumed emitted 68mn tonnes of carbon in 2021. In 2035, those emissions, known as its scope 1 and scope 2 emissions, are expected to be 67mn tonnes. Aramco says that without mitigation these emissions would rise to 119mn tonnes of CO₂e by 2035, given its plans to increase production of oil and gas over the period. Its plans to “mitigate this growth” means the “carbon intensity” of its oil and gas products will therefore fall by 19 per cent over the period from 10.7kg of CO₂e per single barrel of oil equivalent to about 8.7kg, it says.

In comparison, the carbon intensity of Chevron’s operated oil and gas projects in 2021 was 28.6kg, while BP’s was 15.5kg. Carbon Tracker, which analyses the impact of the energy transition on fossil fuel producers, described Aramco’s sustainability report as “heavy on rhetoric and light on substance”. To even assess a company’s compliance with the goals of the 2015 Paris climate agreement, the think-tank says corporate targets need to be set on the basis of an absolute reduction in emissions, include the carbon produced when the products are burnt by the consumer, known as scope 3 emissions, and cover the company’s entire sales and production. “Aramco’s targets don’t meet any of the three of our hallmarks, which we see as prerequisites for climate targets to be potentially Paris-aligned,” says Coffin, of Carbon Tracker. He sees Aramco’s argument that its barrels are “lower-carbon” than others as a distraction, adding that the average scope 3 emissions of a barrel of oil are 430kg CO₂e.

Reducing operational emissions by half will only reduce a barrel’s total carbon emissions by 7 per cent, he says. “That’s playing at the margins and totally ignoring the elephant in the room that you’re still burning oil.” Aramco, however, is not the only oil producer that has not set scope 3 targets. Exxon has no scope 3 target, while Shell and Chevron have only committed to reduce end-use emissions in terms of “carbon intensity” — a relative measure, which allows the carbon produced by oil and gas to be offset against a company’s low and zero-carbon energy products.

The International Energy Agency forecasts that global oil demand may fall from more than 100mn b/d today to 24mn b/d in 2050 if the world successfully cuts emissions to net zero by then. In contrast, Aramco argues that the energy transition will move at a different pace across different markets and that there will be a need for its hydrocarbons “well beyond 2050”. “We only produce oil because people want to buy it, so it’s up to the countries to decide how they want to manage that,” says Olivier Thorel, Aramco’s vice-president for chemicals and hydrogen.

As long as there is demand, he adds, Aramco will aim to meet that in a “reliable way”. It is an argument that has found new support from governments and investors in the past 12 months after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine upended energy markets, sending European countries racing to secure alternative supplies of fossil fuels.

In May, Aramco briefly reclaimed from Apple the title of the world’s most valuable company, as its market capitalisation soared to $2.426tn after oil prices rallied. At the most recent COP climate meeting in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, Saudi officials held discussions about greening the oil industry, while successfully campaigning alongside other countries to keep language on the phaseout of all fossil fuels out of the final declaration. “They are the most powerful market actor right now because of the concentration of capacity that they hold and their supply flexibility,” says Ahmed Mehdi, an oil market expert at Renaissance Energy Advisors, a consultancy.

By 2050 Mehdi thinks Aramco will still be the world’s biggest crude oil producer. However, the company would benefit from being “more transparent about this massive PR assertion that ‘we have the lowest [carbon] intensity in the world’,” he says, adding that verification is key to building trust with emissions reporting. “They have made bold claims. Well then, make the methodology public, show the data.”

There are other strands to Aramco’s plans for longevity even if demand for crude oil eventually enters a rapid decline. The first, petrochemicals, has been a focus since Aramco completed construction of the $20bn Sadara chemicals plant in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province in 2017. Then about 12 per cent of the company’s crude was used to produce petrochemicals. Thorel, a French national who previously spent 15 years at Shell, says Aramco aims to increase that to about a third — approximately 4mn barrels of oil equivalent — by 2030-35.

In 2020, it acquired a 70 per cent stake in Saudi Arabia’s state-owned petrochemicals company Sabic. The speciality chemicals, which can be found in everything from plastic bags to cosmetics and car parts, are generally not burnt and therefore have no scope 3 emissions. However, the shift means Aramco products are likely to contribute to more plastic waste.

The second strand, hydrogen, which is pitched as a low-carbon alternative to fossil fuels, is a more nascent area of focus. In 2020, Aramco produced and delivered the world’s first shipment of hydrogen to Japan in the form of ammonia. Aramco produces hydrogen from natural gas, while capturing the CO₂ generated during the process. It aims to produce up to 11mn tonnes a year of so-called blue ammonia by 2030. At the headquarters in Dhahran a futuristic hydrogen-powered bus is used to ferry important visitors.

Other areas of work at Aramco’s research and development centre include “advanced combustion systems” to lower the emissions of traditional vehicle engines, a “low-carbon synthetic gasoline” and mobile carbon capture technology, which it argues could cut vehicle CO₂ emissions by up to 40 per cent by preventing the fumes from being released. Aramco spent $94mn investigating “sustainable mobility” in 2021 out of a total research and development budget of $607mn. Such initiatives feel more speculative and less likely to see widespread uptake than, for example, hydrogen, says Mehdi.

Yet they also feel more directly aligned with Aramco’s ultimate goal of prolonging the oil era. “Aramco recognises that there is a window of time that is significantly longer than what the west perceives where they can optimise oil,” says Christyan Malek, global head of energy strategy at JPMorgan. “The west is thinking five to 10 years. They’re thinking 20 to 30 years. That makes all the difference.”