Jakarta 2.12am / New Capital City Indonesia - NUSANTARA 3.12am / Canberra 5.12am

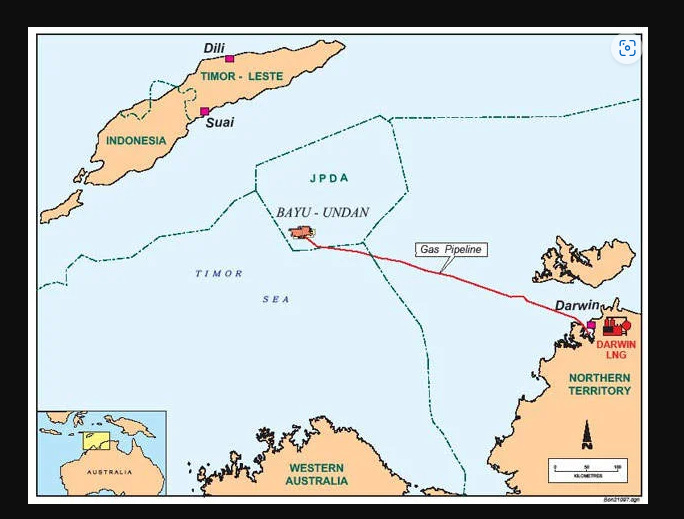

For a long time, perhaps even now, some Indonesians considered Timor Leste's separation from Indonesia, with all of Australia's intervention from 1992 - 1999, because Australia was eyeing an energy block (oil, gas) in the waters or seas between Indonesia and Australia adjacent to Timor Leste.

By pushing Timor Leste to separate from Indonesia, in the minds of many Indonesians who are disappointed by this separation, are accused of Australia's efforts to find the easiest way to control energy resources. Disputes with East Timor will be much easier than disputes with Indonesia.

In the wake of the celebration 78 years Independence Day of Indonesia, remind again that until today, Australia is still facing a dispute with Timor Leste.

The maritime boundary between Timor-Leste and Australia has been the subject of a long-running dispute, dating back to a 1972 agreement between Indonesia and Australia that placed the line much closer to Timor, rather than on the median point between the two coasts. The dispute has held up the development of the Woodside Petroleum-operated Sunrise gas field, which is being eyed for an LNG project. Jurisdiction over the disputed area is defined by the Timor Sea Treaty and the Treaty on Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea, signed in 2006. The treaties defined the Joint Petroleum Development Area, which covers part of Sunrise and all of Bayu-Undan, but put off the finalization of permanent maritime boundaries for first 30, and then 50, years. Timor-Leste first instituted proceedings against Australia in the Permanent Court of Arbitration in April 2014, claiming that the CMATS treaty was invalid because its larger neighbor had engaged in espionage during its negotiations.

Timor-Leste’s government has developed a narrative that maritime boundaries are necessary for completing its sovereignty. This narrative has linked the independence movement to the sea disputes in order to bolster public support against Australia. Consequently, the moratorium on forming permanent boundaries had increasingly become a problem in relations between Australia and Timor-Leste.

In 2015, Timor-Leste’s government initiated a United Nations Compulsory Conciliation under Annex V of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in a bid to pressure Australia into changing its policies on Greater Sunrise.

Timor-Leste’s withdrawal from CMATS is not a surprise. In the opening statements of the conciliation process, Timor-Leste’s representatives flagged this as a likely action.

The careful wording of the joint statement makes it clear that the Australian government “recognises” Timor-Leste’s right to initiate the termination of the treaty. This does not suggest that Australia has substantially shifted its long-standing policies on the Timor Sea. However, the joint statement does indicate that the Australian government recognises that maintaining the CMATS treaty had become untenable.

When Polly Hemming saw the government’s deep-sea dumping legislation, she knew exactly who it was for. The bill allows companies to export their carbon dioxide outside of Australian waters and dump it in international seas. There is a single company for which this is relevant.

“It seems particularly convenient that the Australian government is now in a rush to ratify and pass this sea dumping legislation when the only company it serves is Santos,” says Hemming, director of climate and energy programs at The Australia Institute. “They’re the only company that is proposing trans-border carbon storage.”

At the centre of this story is one of the dirtiest gas fields in the world, Santos’s multibillion-dollar Barossa project. Located about 285 kilometres off the coast of Darwin, it has a carbon dioxide profile of 18 per cent – almost double the amount of the next highest emitting gas currently being converted to liquefied natural gas in Australia. It’s so dirty the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis calls the project an “emissions factory with an LNG by-product”.

This month, Workers at gas projects in Australia voted to strike, which could curb LNG exports just as global competition for the fuel rises. Proposed strikes at Australia’s Woodside-operated North West Shelf, and Chevron’s Gorgon and Wheatstone LNG plants led to the European gas market panicking last week. Between 8-9 August, the benchmark ICIS TTF front-month contract rose by €8/MWh to €38.80/MWh. After 3 days of declines, the ICIS TTF front-month contract climbed again on 15 August, closing at €39.08/MWh. This was driven by the lack of progress in the ongoing negotiations between Woodside and the unions, raising fears of the strike action taking place.

The three Australian LNG plants collectively produce about 10% of global LNG supply. So far in 2023, these three plants have covered at least 25% of the LNG into four of Asia’s largest buyers (Japan, Taiwan, Thailand, and Singapore.

According to Australian labour rules, strike action must commence within 30 days of the union’s ballot. As the vote for Woodside’s workers took place on 9 August, it should be expected the strikes begin no later than 7 September. Meanwhile, Chevron’s workers are expected to vote next week. Additionally, seven-days of advanced notice is needed before a strike can begin. The latest news confirms that negotiations between Woodside and the unions are still on going, with a meeting scheduled for next Wednesday 23 August. There is no clear day as to when the strike action decision might be taken, contrary to information published by other sources that a final decision will be made on Friday 18 August. The duration of the potential strikes remains uncertain. Recent strike action at Australia’s Shell-run Prelude floating plant would not be a good guide as this industrial action was driven by very specific worker grievances, which are not relevant to the unions at North West Shelf, Gorgon, and Wheatstone.

To reach net-zero emissions as required under the safeguard mechanism scheme, Santos says it will capture up to 10 million tonnes of carbon from its Barossa gas field and store it in the depleted Bayu-Undan gas reservoir in Timorese maritime territory. The scale of Santos’s plans dramatically exceeds what carbon capture and storage has so far achieved. Whether or not it is possible, the government’s deep-sea dumping bill makes it legal.

“It’s about as feasible as Santos saying ‘We’re going to put carbon dioxide on the moon’,” Hemming says of the plan. “If you look at all those pipelines involved and what could go wrong in the meantime, the fact that we’re treating it with any kind of credulity is embarrassing.”

Santos recently admitted to the Northern Territory Environmental Protection Authority that the Bayu-Undan carbon capture and storage (CCS) project was “still undergoing technical and economic assessments”.

To exploit the Barossa gas field, Santos will process gas on a floating production storage and offloading vessel, before piping it hundreds of kilometres to Darwin for onshore processing and conversion to liquefied natural gas. This will happen at the yet-to-be-built Middle Arm precinct, where carbon dioxide emissions will exceed the LNG production.

After processing, Santos says CO2 will be compressed and piped nearly 500 kilometres through geologically complicated seas to the near-depleted Bayu-Undan gas field, where it will be stored.

“It’s about as feasible as Santos saying ‘We’re going to put carbon dioxide on the moon’ … the fact that we’re treating it with any kind of credulity is embarrassing.”

If Santos’s CCS project operates at 100 per cent efficiency and success, which according to The Australia Institute is 10 times the current sequestration rate of the world’s largest project, not only would there be a zero net benefit, but it’s highly likely it would increase the project’s overall emissions profile.

“They don’t care if it works or not,” Hemming says. “There is no meaningful consequence or penalty set by the state or federal government if CCS fails. And if it fails in international waters, in the Timorese sea, what are the chances that the government is going to care about that either?”

The world’s current largest CCS project is Chevron’s Gorgon gas plant, located about 60 kilometres off the coast of Western Australia. As with Santos’s Barossa project, Chevron was allowed to build the $US54 billion gas export project on the condition it was capable of capturing all the carbon dioxide emissions from offshore reservoirs and burying at least 80 per cent of the pollutant.

The Chevron project has been held up as an exemplar by the CCS lobby, but after nearly seven years it is operating at just a third of its reported capacity, with no clear timetable or assurances given by the company on when it’ll reach 100 per cent operating capacity – or if it ever will.

Bill Hare, senior scientist and chief executive of Climate Analytics, says the failures at Gorgon “illustrates another general point: that as soon as one starts to dig into the claims of the CCS industry, they tend to evaporate”.

Despite the historical failures of CCS technology and the plumes of pollution it has enabled to be spewed out into the atmosphere, both the Australian and Western Australian governments provided an indemnity to the Gorgon joint venture partners against independent third-party claims.

The WA government has indemnified the GJV, and the Australian government has indemnified the WA government for 80 per cent of any amount determined to be payable under that indemnity.

Although Minister for Climate Change and Energy Chris Bowen didn’t clarify whether or not Santos would be provided with the same indemnity, a spokesperson for his office said the Barossa project “will be required to be zero reservoir C02 from day one, consistent with international best practice”.

Despite the mountain of technical challenges and opposition from the Tiwi Islands’ Traditional Owners, Santos plans to begin producing gas from Barossa in 2025. The company’s infrastructure to dump carbon in the Timor Sea will be ready in 2027.

Speaking from Oslo, climate and energy analyst Ketan Joshi says the fundamental story of CCS is that it doesn’t work. “It is a rhetorical tool used to justify new fossil fuels and, on the hardest of math, it causes much more emissions than it prevents.”

In northern Australia, the Barossa project is inextricably linked to a web of other major fossil fuel investments and infrastructure. The economic viability of the $1.5 billion government-funded Middle Arm precinct in Darwin – and by extension, the export of fracked gas from the Beetaloo Basin – has a dependency on the Barossa gas field reaching production.

Waiting alongside Santos is Italian multinational energy company Eni, which controls the Evans Shoal gas field – a “carbon bomb” with a 27 per cent carbon dioxide profile that makes Santos’s Barossa project look clean.

In May 2021, Eni and Santos signed a memorandum of understanding that seeks to identify “synergies and sharing of infrastructure”. Without Santos’s infrastructure, the viability of Eni producing gas from Evans Shoal is thrown into jeopardy.

The key to unlocking all of this, as well as enabling the government to rebrand Middle Arm from a petrochemicals plant to a sustainable development precinct, is Santos’s CCS plans and the government’s deep-sea dumping bill.

In response to a series of detailed questions, Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek said “this bill implements Australia’s international obligations under the London Protocol”.

Bill Hare says otherwise: “The only reason Australia is proposing to dump CO2 under the seabed is because that’s what the fossil gas industry wants. There is no ‘obligation’ to do this – the bill only ensures that any CO2 sea-dumping operations would be consistent with the London Protocol.

“Doing this would be shifting Australia’s pollution problem somewhere else, and to a poor, less-developed country. The federal government will want to deduct the transported CO2 from Australia’s national emissions under the Paris Agreement, putting the responsibility onto Timor-Leste if this CO2 is subsequently released.”

The Bayu-Undan gas field is a site of profound historical injustice. Its riches were so irresistible the Australian government infamously enacted a clandestine operation to gain an upper hand in maritime negotiations with Timor-Leste.

The Bayu-Undan is located 500km offshore Darwin, Australia, in the Timor Sea, and is 250km south of East Timor. It is equipoised at the boundaries of block 91-12 (60%) and 91-13 (40%), under Area A of the Australia/Indonesia Zone of Cooperation. The fields are located on the same 160km² structure, in 80m of water.

The operator is ConocoPhilips, which has a 57.2% stake. Partners are Eni (11%), Santos (11.5%), Inpex (11.3%) and Tokyo Electric Power and Tokyo Gas (9.2%). The project received an award for technology from the Asian Civil Engineering Coordinating Council in Taiwan in 2007.

Bayu was discovered in early 1995, when the Bayu-1 well intersected a 155m gas condensate column, at a depth of 897m.

This tested 2.54m³ of gas a day and 5,250bbl of condensate. The follow-up well, Bayu-2, tested 991,000m³ gas a day and 2,000bbl of condensate from a 52m interval.

In July 1995, Undan was discovered 10km north-west of Bayu, where a 139m gross hydrocarbon column tested 1.6 million cubic feet of gas a day and 3,900bbl condensate a day. The total recoverable field of reserves ranges between 350 and 400 million barrels of hydrocarbon liquids and 3.4tcf of gas.

The 25x15km field will need approximately 26 wells over its lifetime to produce the reserves.

The field life is estimated to be 25 years. Commercial production began in April 2004, delivering 115,000bpd of condensates and LPG.

The project was developed in two phases. The $1.8bn gas-liquids first phase involved the production and processing of wet gas, the separation and storage of condensate, propane and butane, and the re-injection of dry natural gas back into the reservoir.

The phase also involved the construction of a remote wellhead platform, a drilling, production and processing platform and a compression, utilities and quarters platform. The recovered liquids are sent to floating storage and offloading (FSO) facility.

Total Integrated Group Approach, an alliance between Fluor Daniel and Worley, was selected as the engineering and procurement contractor.

The second phase of Bayu-Undan’s development, the gas phase, began production in February 2006, and cost $1.5bn. This involved the extraction of lean gas from the reservoir and transportation to Darwin, on Australia’s northern coast, via a 500km, 26in pipeline, where it is liquefied at a single-train processing plant at Wickham Point, then shipped as LNG to customers Tokyo Electric Power Company and Tokyo Gas in Japan.

It has a production capacity of 3.24 million tonnes a year, and ConocoPhillips has entered agreements with the two companies to supply three million tonnes of Bayu-Undan LNG a year over 17 years.

The plant was built under a lump-sum turnkey contract with units of the Bechtel Corporation, which subcontracted the construction of the LNG storage tank to a consortium of Theiss of Australia and TKK of Japan.

The field is producing from ten production wells. Four gas injection wells and two water injection wells were drilled.

The third phase of Bayu-Undan’s development will be completed in three stages with work on the first stage beginning in 2014. The first gas was produced under Phase III in April 2015.

The third phase comprises drilling and tying-back at the Bayu-Undan field with two subsea production wells providing production assurance. The drilling of additional production wells is evaluated in the next stages.

The Bayu-Undan development complex includes a wellhead platform, a compression, utilities and quarters (CUQ) platform and a drilling, production and processing (DPP) platform. The wellhead platform is an unmanned structure that was installed in April 2006 and consists of 17.7×24.4m topsides, supported by a four-leg 1,319t jacket.

The CUQ and DPP platforms both consist of an eight-leg steel jacket, slotted to accommodate topside deck float over. The jacket dimensions are 48m x 50m, with a height of 90m.

The topsides were built at the Hyundai fabrication yard in Ulsan, South Korea. The CUQ topsides weigh 11,500t and are 72m-long, 80m-wide and 31m-high, while the DPP topsides weigh 13,900t and are 65m-long, 64m-wide and 41m-high.

The processing equipment for the Bayu-Undan fields includes three 23MW gas-turbine-driven injection compressors, two 7.5MW gas-turbine flash gas compressors and two turboexpanders. It has high-pressure (100/310bar) column vessels and four gas-turbine-driven generators.

The topsides were installed in November 2003 by Dockwise, under a contract awarded by Perth-based Clough-Aker Joint Venture covering their transportation and installation.

The integrated condensate and LPG storage offloading facility, the first of its kind at the time, can store 820,000bbl (130,000m3) of condensate, 300,000bbl (95,000m3) of propane and 300,000bbl (47,500m3) of butane. It has no propulsion system of its own, and is 248m-long, 54m-wide, with a tonnage of 150,000dwt. Accommodation is available for 60 people.

The purpose-built FSO, named the Liberdade, was built by Samsung Heavy Industries, launched in Korea in September 2002 and permanently positioned offshore in the field about a year later. It processes the condensate and LPG and stores them before they are loaded onto tankers for export. As such, it is designed to exploit remote oil and gas reserves that might otherwise be stranded for decades.

Flowlines between the WHP and DPP consist of an 8km, 18in carbon steel CRA-lined production line and an 8km, 16in injection line.

Flowlines between the DPP and FSO consist of a 12in condensate line, a 6in carbon steel propane line, a 6in butane line and a 4in carbon-steel fuel gas line, all 2.3km-long.

The combined service contract for the project development was given to Neptune Marine Services in December 2009. The contract work comprises pipeline inspection surveys, grouting services and ROV inspection of the project’s pipelines and platforms.

Trelleborg provided high-performance technology pipe penetration seals for the field under a $2m contract.

Territory Diving Services provided diving services for the project in February 2005.

ConocoPhilips contracted URS to carry out geotechnical studies at the field and assisted in the preparation of the Environmental Impact Statement.

In October 2011, Clough AMEC joint venture was awarded an extension contract to provide maintenance services at the field.

FMC Technologies was contracted for the supply of subsea equipment for Bayu Undan third Phase project, in May 2013.

JDR Cable installed subsea production umbilicals in the third phase of the Bayu-Undan Field development in the Joint Petroleum Development Area (JPDA) in Australia in January 2014.

Bombora-ESP was contracted to provide construction management services for the Bayu-Undan Phase III in July 2014.

SpeedCast was contracted to deliver high-speed satellite communications services between ConocoPhillip’s offshore production facilities in the Bayu-Undan field and regional headquarters in Perth, Australia.

In December 2015, Wood Group received a multi-year contract to provide brownfield engineering services for the project.

Clough AMEC received a three-year contract from Conoco Phillips to provide asset support, operations and maintenance services to the Bayu-Undan offshore field development.

Based on the now renegotiated sea boundaries, the Commonwealth’s commitment to corporate riches robbed Timor-Leste of an estimated $5 billion of revenue at a time when it had gained independence from brutal Indonesian occupation. It’s a significant number, considering Timor-Leste’s general state budget last year was $1.95 billion.

After decades of exploitation, Timor-Leste is staring down deep economic duress. The country’s precarious economic situation, paired with its fragile geology and infrastructure, leaves it vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

Bree Ahrens, a campaigner for the Environment Centre NT, says the proposed arrangement to dump carbon in Timor-Leste waters should be viewed in this context. She is adamant this is a story “of carbon colonialism”.

“Santos might not exist in 20 years, but the CO2 from Barossa will,” she says. “And given the future questions around Timor-Leste’s financial resources, it’s a heavy burden to bear. And it’s imperative that Australia be clear about what their responsibility in regard to that is.”

A series of detailed questions was sent to Santos but the company declined to comment. The deep-sea dumping bill has passed the house of representatives and is currently moving through the senate, where it is expected to pass.

=========END————

Thank you, as always, for reading. If you have anything like a spark file, or master thought list (spark file sounds so much cooler), let me know how you use it in the comments below.

If you enjoyed this post, please share it.

______________

If a friend sent this to you, you could subscribe here 👇. All content is free, and paid subscriptions are voluntary.

——————————————————————————————————

-prada- Adi Mulia Pradana is a Helper. Former adviser (President Indonesia) Jokowi for mapping 2-times election. I used to get paid to catch all these blunders—now I do it for free. Trying to work out what's going on, what happens next. Arch enemies of the tobacco industry, (still) survive after getting doxed.

Now figure out, or, prevent catastrophic situations in the Indonesian administration from outside the government. After his mom was nearly killed by a syndicate, now I do it (catch all these blunders, especially blunders by an asshole syndicates) for free. Writer actually facing 12 years attack-simultaneously (physically terror, cyberattack terror) by his (ex) friend in IR UGM / HI UGM (all of them actually indebted to me, at least get a very cheap book). 2 times, my mom nearly got assassinated by my friend with “komplotan” / weird syndicate. Once assassin, forever is assassin, that I was facing in years. I push myself to be (keep) dovish, pacifist, and you can read my pacifist tone in every note I write. A framing that myself propagated for years.

(Very rare compliment and initiative pledge, and hopefully more readers more pledges to me. Thank you. Yes, even a lot of people associated me PRAVDA, not part of MIUCCIA PRADA. I’m literally asshole on debate, since in college). My note-live blog about Russia - Ukraine already click-read 4 millions.

=======

Thanks for reading Prada’s Newsletter. I was lured, inspired by someone writer, his post in LinkedIn months ago, “Currently after a routine daily writing newsletter in the last 10 years, my subscriber reaches 100,000. Maybe one of my subscribers is your boss.” After I get followed / subscribed by (literally) prominent AI and prominent Chief Product and Technology of mammoth global media (both: Sir, thank you so much), I try crafting more / better writing.

To get the ones who really appreciate your writing, and now prominent people appreciate my writing, priceless feeling. Prada ungated/no paywall every notes-but thank you for anyone open initiative pledge to me.

(Promoting to more engage in Substack) Seamless to listen to your favorite podcasts on Substack. You can buy a better headset to listen to a podcast here (GST DE352306207).

Listeners on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Overcast, or Pocket Casts simultaneously. podcasting can transform more of a conversation. Invite listeners to weigh in on episodes directly with you and with each other through discussion threads. At Substack, the process is to build with writers. Podcasts are an amazing feature of the Substack. I wish it had a feature to read the words we have written down without us having to do the speaking. Thanks for reading Prada’s Newsletter.

Wants comfy jogging pants / jogginghose amid scorching summer or (one day) harsh winter like black jogginghose or khaki/beige jogginghose like this? click

Headset and Mic can buy in here, but not including this cat, laptop, and couch / sofa.

Whoa I didn't know....