NYC, San Francisco Work Harder, Not Being Lazy (begged WFH) like Jakarta, So I Care about you

At least 7% of the total 71,268 times to reads. That's my note about “Kualat Starap (Start-Up)” read in LinkedIn. 7% of 71,268 reads come via LinkedIn. I was read the person who posted - uploaded my note on LinkedIn. And he said (coincidentally not female but male), or he pretended that I hate startups. No. I saw he’s very rich, or at least was studying overseas. I haven't. He said (very easily) I hate startup. He never felt / suffered like me: 6 years not proper Lebaran, because 7 years building starap (start-up) and living in dormitory-mess, in 2 companies. 7 Years, in dormitory-mess. Don't have a proper to “jalan-jalan enak-enak”. Was in abroad just to learn about programming. Bleeding 7 years without proper Lebaran. The more bleeding: Courir, or all “IN FIELD” team, “IN SITE” team, don’t have a privilege like MOST Tech Worker (at least) Indonesia, nearly 3 years (enjoyed) WFH.

With bleeding years, I have never envied friends, former friends, people I once cared about, worked in a super luxurious and very high-tech building, and suffered trillions of losses (IDR 8 trillions, 10 trillions, I don't know, one of part of her failure and also her teammate failures) and have now moved back to work in other companies. 5 Years failed continuously for IPOs (in Indonesia). I sent very proper birthday gift 3 years consecutive among covid to her three years in a row.

Layoffs have come to tech. Unprofitable companies going through a restructuring be like “this is the start of a new chapter for us” yeah chapter 11 in U.S. or directly goes to KPPU in Indonesia. It's easy to say that COVID pulled forward demand, businesses staffed up to meet it, and now they're pulling back. But something deeper happened. COVID pulled forward their future.

They rushed forward to meet it, but now they're fighting for survival. In normal times, growth businesses are deliberate about expansion. They spend up to a decade building a strong core product w/ sticky user base and go-to-market muscles like sales and customer success. They use their strong core to fund their next opportunity. Build some interesting shit, send it over and if I like it, you're part of the team. Bonus points if you're crazy, like memes and a little unhinged. (BUT) COVID fucked that all up.

Not just limited to developers (never offshore unless you have local team):

- Sales

- Marketing

- BizDev

Really depends on where you want to spend organization time. If you have no time for prospecting, offshore for a short time. (Again), unprofitable companies going through a restructuring be like “this is the start of a new chapter for us” yeah chapter 11. "People are very unfair when they accuse the big investors of secretly running the world by controlling trillions of dollars of capital and using that to further the interest of global elites" - yes fine agreed but say that from your front porch or whatever.

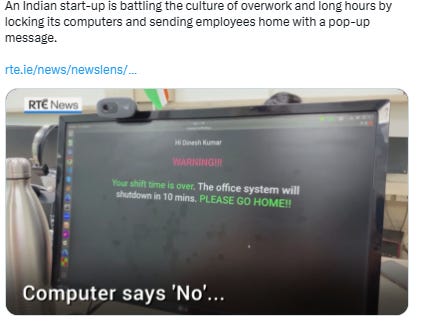

Companies do not transition from this temporary phase because the unit economics are good (cheaper labor) and their teams are happy (don't have to do work which is generally repetitive). Once you don't move away, your ability to change slowly erodes to zero. One of the biggest advantages that still exists is figuring out how to run a good local dev team, and manage them efficiently from somewhere else. Some orgs do it but it is still blatantly inefficient given natural sleep schedule constraints. And how to handle attrition/loyalty. Go Home (after 5pm in Office)., then get better sleep.

About WFO vs WFH, let’s reflect with / compare with other cities but better than Jakarta. The thing that makes London, NYC, San Francisco, Dublin, Tallinn, Tokyo great is not that they're popular locations.

It's because you see people around you working harder and do so yourself. Say you leave the office at 6pm. There's always a guy in the same building, on the same floor, still working. In other cities, you don't see this often. Regardless of the type of work, if the employer wants their worker to be present, so be present. No need to be a bitch about it, some parameters need to be set, some adjustments will be applied later. And then, work harder at the office.

Everyone leaves at the same time, they watch a game, they grab a drink at the local bar, whatever. That’s why WFO (Work From Office already, or abruptly, reset-and-to-be mandatory in London, NYC, San Francisco, Dublin, Tallinn, Tokyo amid “chaos - downturn of Tech sector”: work in office will be more optimal rather than Work From Home, because, again, in the same building (of office), other people work harder, so you devoted to work more harder. Yes, bullshit, Tokyo, NYC etc also have a crowded traffic like Jakarta. Please don't make excuses about KRL (Commuter Line), MRT, Busway, or you being lazy.

In big cities, you see your competition work harder than you, and you realize if you don't work harder, they are going to overtake you. Everyone talks about how living standards are higher outside major cities, you save more, etc. but people don't mention that most people stop pushing themselves once they move out because they don't see their competition (if you don't see them, you think they don't exist). If you can continue to push yourself and hold yourself to a standard no one else around you holds themselves to, then building in a random city is worth it.

But as your org grows, you hire locally, and chances are those people don't know about your standard. Slow regression to the mean. Nothing groundbreaking for an experienced investor but it reinforces lots of good concepts & there’s good examples from lots of different industries. There’s an interesting chapter about how (Jonn Maynard) Keynessian - ish Investors adapted his investment strategy in the aftermath of the great depression to build a company. Either they’ve become complacent & have fallen behind on innovation because they thought their search monopoly would last forever, or they’re an organization capable of adapting to a new reality. One way or another competition is how we’ll find out. Started as more of an active trader & used a large amount of leverage but after experiencing a large drawdown, changed to a style similar to Buffett/Graham. BUT, BUT, again, Covid fucked everything.

With the age of easy money clearly over I feel like there’s a spectrum of possibilities for aspiring founders - on one end you invent or are close to a scientific breakthrough & you start a business to commercialize the innovation. On the other end it’s like leveraging existing tech & finding an innovative way to sell goods or deliver services. For the former, examples would be like the transistor or more recently the gpu. invention happens, you start a company to test the waters & see if there's a market for the new innovation. For the latter end of the spectrum examples would be amazon, alphabet google or airbnb which used developments in tech to create a previously unimaginable kind of business. For example: Twitter under Dorsey regime say “WFH forever”, but Elon Musk found that Twitter nearly went bankrupt / Chapter 11 after bought Twitter, so currently “brutal work, hardcore work” WFO in Twitter. Obviously lots of examples in the middle where a business is born from some parts harnessing a scientific breakthrough & some parts an innovative biz model.

This line of thinking is why one of my hot takes is that crossover funds could potentially if executed with discipline - careful - proper be vs successful & lucrative for partners & LPs because if shrewd investors understand what works in public market dynamics why not buy equity pre IPO. Indonesia you can see flop (after IPO) of $GOTO $GOJEK $TOKOPEDIA and in Singapore about $GRAB

i think there was this meme of like “great companies burn money forever to get to an impenetrable scale” combined w money being free & founders having the leverage and so incentives ended up way out of whack.

COVID fucked up things for tech companies in two ways:

1) It created an explosion in their core business. Had to staff up to meet demand

2) It pulled forward their future. They started eating through their end market. Investors wanted to know - What's next?

In normal times, growth businesses are deliberate about expansion. They spend up to a decade building a strong core product w/ sticky user base and go-to-market muscles like sales and customer success

They use their strong core to fund their next opportunity.

(again) COVID fucked that all up.

So companies acted fast. They acquired companies with inflated stock. They launched new products and services. All while trying to meet insane demand in their core

Launching a second/third Act in normal times is incredibly hard. Most companies fail. This was something else. Now it's unwinding, and these companies are out on a ledge fighting for their life:

1) That stable core that was funding the 2nd Act doesn't look so stable anymore

2) Demand is weakening, and they're overstaffed

3) What the hell are we doing with a 2nd act when Act 1 is at risk?

Expect to see RIFs and layoffs continue. Tech companies need to overhaul their core businesses. They're re-evaluating their COVID-forced expansion. Funding is uncertain.

“You have to think about this practice [of investing] the same way you think about a business.”

“The framework we apply is one that applies to a lot of industries we study. The investment industry is bifurcating between robots and what we call 'deeply human investing.'”

“If you're a fundamental investor you have to understand what the skillset of a human is and what the skillset of a machine is, and you have to continue to become greater at where humans are relatively advantaged. If we were to go play a game against the computer in chess, we already know who's going to win. That's like competing against the quant in a linear pattern that's been public for a long time against known alternative datasets.

If we could change the rules of the game right before we play, and the computer didn't know the rules and we knew the rules, I think we would win the game.

Patterns that are newly public, that are geometric. People are geometric, they impact organizations because they hire As and capital allocate in an ‘A way,’ that's geometric. That's where we believe we're advantaged.”

This fits perfectly with playing in private markets where success is determined by access, relationships, and more qualitative analysis.

It also matches Ellenbogen’s statements about small-cap growth investing being both creative and complex:

“Dispersion in small-cap growth stocks, the rewards of success are greater and the penalties for failure are more severe. The broader interpretation is that developing and maintaining a creative process that encourages unconventional or controversial views of business models is essential to success in small-cap growth investing.”

“Growth investing is undeniably a complex problem. The concept of complexity applies particularly well to industries undergoing structural change. Our work demands that we interpret a constant stream of new, often-surprising data points and place them in an appropriate context. As a result, when we are measuring the probability of different outcomes, we have to rely heavily on our qualitative understanding of business strategies and industry trends.”

"Investing in small-cap growth stocks is an immensely creative process, where creativity and success are defined by the ability to see what others—most market participants—don’t see."

Ellenbogen is acutely aware that long-term compounders are rare and account for a large share of the market’s performance (see also Henrik Bessembinder’s studies for more info on the distribution of returns).

“We began to study an elite group of these compounders, across the universe of small-cap, publicly traded companies since 1996. We found that small-cap compounders—U.S.-listed companies that began with $1 billion to $6 billion market capitalization and subsequently generated a 20% total return compound annual growth rate (CAGR) over a 10-yearperiod—are rare and extremely valuable to returns over time.

Since 1996, there have been 463 instances where small-cap companies passed the 10-year return hurdle to be designated as a compounder. The median number of small-cap compounders was 28 per year, or 2.4% of eligible companies during the 10-year period.”

“An annual cohort of small-cap compounders contributed nearly 35% of the total market appreciation over the 10-year period. Said differently, compounders were nearly 15 times more impactful to the market’s returns than the number of companies would imply on its own.

This data reaffirmed our views that small-cap compounders are rare—historically 1 in 40 companies achieved the feat—and the stakes are very high for investors. This reminds us that, as growth investors, we need to grow our roses and cut our weeds.”

His goal is to participate in the compounding for as long as possible. He can invest in a company while private and average up through subsequent funding rounds or by adding to the position after the company goes public. This is part of his pitch to founders as well:

“We do not invest in private companies merely to guide them to an initial public offering or benefit from private-public arbitrage. Rather, we want to serve as a stable partner that encourages businesses to compound wealth in the long run through durability and sustainability.”

He is comfortable averaging up if the company performs well and turns out to be one of his rare compounders.

“Our goal is to buy shares in our successful early-stage growth companies as their stock price is rising, but in our view, has not yet peaked. We call this “dollar cost averaging up.””

“When we invest in a private company, we tell the chief executives that we seek to deploy capital in companies that can become long-term holdings. Our goal is to compound wealth in these companies as they scale and transition from early-stage to durable growth companies, and we often increase our stake as they scale.”

At the core of Ellenbogen’s framework is the idea that the most successful growth companies have multiple acts. After exhausting their initial growth potential, they must transition to a second act – new markets or products. Ellenbogen admits the futility of trying to predict how this will unfold. Instead, he focuses on identifying the driver that is a necessary condition: exceptional leadership willing to invest long-term and build out processes that will support a larger scale company.

“We seek companies that have the potential for an Act 2. These enterprises have the ability to find a second phase of growth—a new product, additional market, or innovation—after their first growth engine, or Act 1, has run its course. Act 1 companies that successfully transition to Act 2 have been critical to our outperformance, and we aim to partner with them as early as possible.

When we look at an early Act 1 business, we want to know that it is building the people, processes, and systems necessary to keep winning at scale. We care about management’s willingness to invest for the future, not just its ability to execute in the present.

Transitioning to Act 2 requires a number of skills, including the ability to properly balance customers, employees, and shareholders; to construct a strong corporate culture; and to foster an ownership mentality. But most importantly, managers need the ability to adapt and transition.

Inevitably, the Act 1 to Act 2 transition will result in a challenging period, and transitions are difficult. Vital to doing this successfully is a commitment to intellectual honesty, diversity of thought, and emphasis on organizational adaptability.”

This is part of his conversation with private companies as well:

“One of the principal reasons we invest in private companies is to encourage them to think about scale in people, processes, or systems. Often, our best contribution is introducing companies to outside executives who understand the concept of scale.”

“During the initial growth period, management teams focus on investing in their products to achieve product-market fit, building solid initial leadership teams, and solidifying unit economics that work at scale. Most investors spend time thinking about the size of the company’s addressable market and its potential to demonstrate a competitive edge in Act I alone.

Even at the beginning stages of a company’s expansion, we look beyond Act I and understand whether the business has the potential for a second act.”