Penyelenggara Sistem Elektronik (PSE, or PSESO -- Private Scope Electronic Systems Operator)

*update 1 Agustus 2022; 20.22 WIT:

Sudah 67 jam 22 menitan dari aturan blokir, tapi Kaesang tidak marah-marah di Twitter. Pak Plate pasti ngomong dulu bukan hanya ke Jokowi tapi bahkan ke Kaesang (literal punya bisnis eSports) kalau bisnis ini terdampak regulasi sama rata ke semua PSE (Penyelenggara Sistem Elektronik). Jamak sekali Menteri lebih takut Presiden or keluarganya.

========

All I Cared About Was The Truth

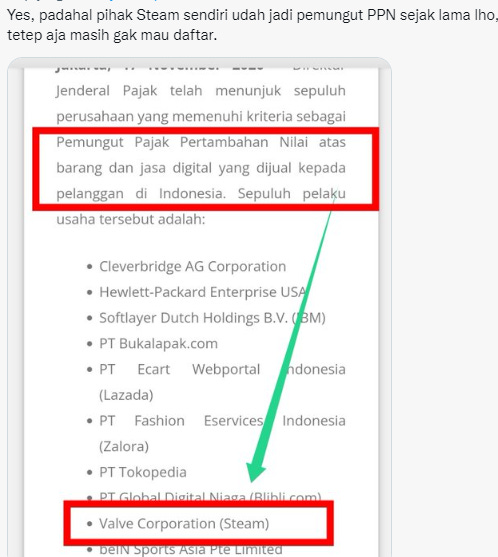

(per 17 Agustus 2022, saya memadukan investigasi terbaru dari Antonia Timmerman - wartawan Rest of World (16 Agustus 2022), serta Kevin Ng - wartawan Coconut (April 2022), serta Ed Davies & Stanley Widianto - Reuters (16 November 2019), terkait regulasi lain yang saling bertaut dengan PSE. Khusus pada laporan Antonia dan Ed-Stanley, nyaris mirip, hanya sedikit berselisih angka dollar, kemungkinan karena volatilitas nilai Rupiah terhadap US Dollar. Menurut Ed-Stanley, Kominfo sudah pernah mempersiapkan draft/rancangan aturan sebesar US$ 36k sejak 2019 sebagai basis denda atas pelanggaran online, sementara Antonia menulis US$ 33k. Dirujuk pada nilai Rupiah pada 2019 dan 2022, dibulatkan bahwa kominfo mempersiapkan regulasi berbasis denda dengan angka denda mencapai 500 juta rupiah. Khusus Antonia mungkin lebih spesifik karena Antonia menambahkan “denda sistematis” ini berlaku jika dalam 4 jam pihak PSE gagal menghapus konten yang dianggap melanggar):

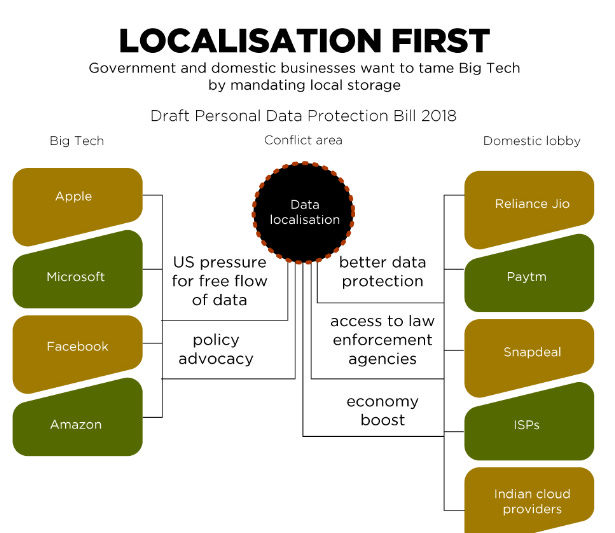

Tech Companies are starting to face legal and financial consequences for their alleged use of dark patterns, deceptive website or app user interfaces used to trick or pressure consumers into making choices they otherwise might not. Less than two years after Indonesia introduced a set of controversial internet laws, officials have plans to deploy new methods to enforce them, including charging what could amount to thousands of dollars in fines to platform companies that refuse to take down content considered “unlawful” by government authorities.

The plan, which was detailed in internal presentations given to leading tech companies operating in the country, offer a window into how Indonesia plans to implement some of its harshest laws governing digital platforms and content moderation. The plan comes amid a growing number of other countries in the region tightening controls over how social media platforms operate within their boundaries. In recent years, Indonesia has joined countries like Myanmar, Cambodia, and Vietnam, where the governments have proposed or are using legal and bureaucratic tools to deploy harsh cyber laws to impede the individual rights of civilians.

In early January, the local teams of global tech companies such as Google, Meta, Twitter, and ByteDance received an invitation for a two-day virtual meeting with Indonesia’s Ministry of Communication and Information Technology, also known as Kominfo. Joined by high-profile regional e-commerce and telco companies, they gathered on Zoom to listen to a presentation by Teguh Arifiyadi, a ministry official, about the government’s plan to enforce its updated internet laws, namely the Law Regarding Electronic Information and Transactions (ITE Law), Government Regulation 71 (GR 71), and Ministerial Regulation 5 (MR5).

During the meeting, Mr Teguh Arifiyadi told attendees that each of the companies would have to register as a Private Scope Electronic Systems Operator (PSE) in Indonesia. Once registered, platforms would then be obliged to take down any content the government deems “unlawful” — a broad label that could apply to everything from pornography to making fun of the president.

According to a senior official at a social media platform that attended the meeting, Arifiyadi told the gathering that companies that failed to comply within the turnaround time could face fines or risk getting blocked. One estimate for the first offense, according to calculations based on another presentation document shared, could reach as much as $33,000 per violation.

The latest version of the document, which was finalized after the January meeting, details indexes for calculating fines based on the company’s gross revenues, compliance rate, and types of content, among other indicators. The new measures outlined in the document dictate that once companies are notified of a takedown notice, they have 24 hours to take down content, and just four hours to take down content labeled as “urgent.”

The social media platform official, who asked to speak on condition of anonymity because he feared reprisals by authorities, said that the meeting’s participants — particularly those working for social media companies — were shocked. Definitions surrounding “prohibited content” were too broad, and if implemented on the thousands of pieces of content each platform churns out every day, they could be forced to pay hundreds of million dollars overnight, significantly impacting operating costs in the country.

“We told Kominfo that vague definitions in the regulation would create confusion among businesses and a murky investment climate… [but] they seemed to hear us half-heartedly,” the platform official told.

Rofi Uddarojat, who heads public policy and government relations at the Indonesian E-commerce Association and regularly attends meetings with Kominfo regarding the regulation, told Rhe also raised concerns about the proposed changes. “We wanted a clear format and standard for takedown requests and a maximum limit for the number of those requests,” he said. Despite these concerns, he claims Kominfo pushed through with the largely unchanged proposed measures.

Indonesia’s new content moderation regulation is one of the strictest digital censorship laws in the region. MR5 came into effect in 2020 and the GR 71 in 2019, but specific measures were needed to make the laws binding. Several government agencies including Kominfo, the Ministry of Finance, and the Coordinating Ministry for Political, Legal, and Security Affairs then drafted the necessary requirements, according to an attendee of the Kominfo meeting. Kominfo announced its collaboration with the finance ministry in an official statement.

“It is simply about expanding state power in cyberspace,” said Gatra Priyandita, an analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. Priyandita said that the law will hurt smaller tech companies that have fewer resources to ensure timely moderation. But, even the world’s biggest tech platforms could face challenges, particularly if they are requested to take down information concerning issues that are taboo in Indonesia, but not in the U.S., such as conversations around the LGBTQIA community or West Papua, Priyandita added.

“Having to respond a lot more quickly and without court orders makes it a lot more complicated for the bigger tech firms,” he said. “Four hours is a bit tight… if there’s a lot of requests to take down information at the same time, I guess it will bog down the company in question.”

Kominfo is known to have requested takedowns for thousands of pieces of content in a month, sometimes more, according to internal transparency reports by leading tech companies. Between June and December 2021, Kominfo asked Google to delist over 500,000 URLs across its search engine, the company’s transparency report showed. (The company eventually delisted only .03 percent of the requested URLs.) Twitter reported that it received legal demands to remove content from nearly 30,000 accounts between July and December 2021.

Kominfo asked his company to take down thousands of pieces of content at one time. Under the new regulation, that could translate to millions in fines. The ministry’s document also stipulates that if a platform fails to take down content, Kominfo would double, then triple the fines, before eventually blocking the platform.

Government facing a bigger dillemma because a brutality, violation on online platform also rocketing year by year. But in other side, if government regulated, pundits says “expanding state power in cyberspace; surveillance by the state”.

As is common in Asia, light skin color is fetishized in Indonesia due to, among others, a relentless multi-million dollar skin bleaching industry and a pop culture (k-pop/Korea Pop culture; or wibu Japan Pop culture) that favors women with fair complexions.

In Indonesia, that fetishization is also bound to generations of resentment towards the racial minority, with the mass rapes of Chinese-Indonesian women in 1998 being one of the darkest example of that hatred to the rich - minority (Chinese Overseas) being acted out in the country’s history.

Like many other victims, there is often a strong racial element in the online sexual abuse women. Many are referred to online by “amoy” or “chindo”, a derogatory term referring to Chinese-Indonesian women that is still widely used in everyday conversation and in online forums to this day. Thousands of Twitter accounts that regularly shared intimate photos and videos of Chinese-Indonesian women. Often, they repurposed those images to create frighteningly vulgar and invasive content of their own. Of those thousands, we found 155 accounts focused specifically on abusing, sexualizing, and fetishising Chinese-Indonesian women. Many of those accounts had significant social media followings, ranging from hundreds to thousands. All of these accounts are still very active, with some newly created in 2022.

The perpetrators hide their true identities and often change their handles to avoid prosecution or getting reported by the victims. Many use backup accounts they can immediately switch to if their main account gets suspended. If they were an army, then one particularly relentless predator, who went by three different handles from 2021 to 2022, would be one of their generals. One labeled himself a “cum-tributer,” which is exactly as repulsive as it sounds, and a “ratings agency,” reposting private photos of many Chinese-Indonesian women while scoring their physical attributes.

And then there are the impostor accounts, who assume the identities of their victims to engage in sexual fantasy role-play for their own and their followers’ gratification. Often, these accounts delve into racial dynamics; specifically, they act out scenarios in which Chinese-Indonesian women become submissive to the desires of another Chinese overseas men or to be desires pribumi (a loose term to describe native Indonesians) men. One prolific twitterati in Indonesia (he’s Chinese overseas) argues that rocketing cases “fetishising” Chinese-overseas women in Indonesia may be just from other Chinese-overseas men. He’s not confident the fetishising came (dominant) from “pribumi”. The fact that, after 1998, more Chinese-overseas in Indonesia living in “very strict”, “very exclusive” security (in the school, or home) may relevant with the logic that only Chinese-overseas man knew and get a exclusive photos from another Chinese-overseas women (if these photos is actually never uploaded by women side via social media).

These accounts only represent the tip of the sleazy iceberg. They make up a highly coordinated, highly active community, obtaining victims’ personal images – mostly from social media and content sharing platforms – before trading them among each other. The images then spread like wildfire; once one is shared, it seems nothing can stop its circulation.

This never-ending non-consensual sharing of intimate images shows a systematic failure to protect sexual violence victims in Indonesia, both offline and online. Thanks to the new law, cyber gender-based violence is now unambiguously categorized as a type of crime. It specifically defines the taking and/or spreading of intimate images without consent as a crime punishable by up to four years in prison. Victims are now legally entitled to legal representation and psychological counseling, as well as compensation for material and immaterial damages. Yet it remains to be seen how it will interact with existed controversial Indonesian laws: the Electronic Information and Transaction ACT (UU ITE) and the Pornography Law, and now another (plan/draft) regulation by Kominfo/Telco Ministry – “fine based / fine centric regulation”, given just four hours to take down content or face as much as $33,000 per violation in fines. Laws are considered to be ambiguously-worded and have been used, time and time again, to criminalize victims instead of perpetrators.

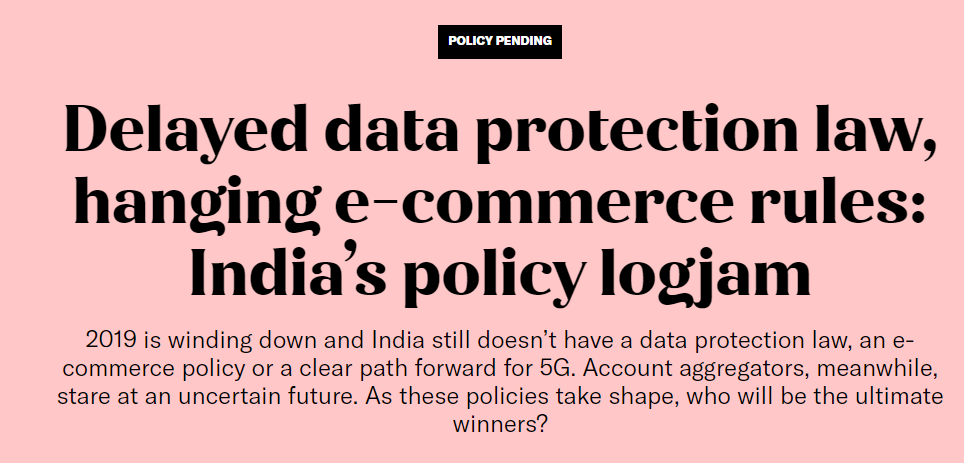

Mr Johnny Gerald Plate, new Telco Minister, who was sworn in October 2019, said in November 2019 that the existing rules to protect data were spread across many laws and needed to be brought together under one law. He aims to bring in a new law to protect personal data by next year as it follows in the footsteps of Southeast Asian neighbours such as Singapore and also the European Union.

The government had a “roadmap to data sovereignty” to reflect the growing importance of data and planned to establish the new law in Southeast Asia’s biggest economy. The unique situation: Mr Plate was born in Ruteng NTT, a very small town and secluded area in Indonesia. His spirit to expand more aggressively about broadband across Indonesia, very solid, because he’s Ruteng - native, with less infrastructure (including communication infrastructure). The move comes amid wider regional efforts by Southeast Asian governments to demand action from global tech giants on content regulation and tax policy.

The stakes are high for both governments, which are counting on the digital economy to drive growth, and internet companies, which view Southeast Asia’s social-media-loving population of 641 million as a key growth market.

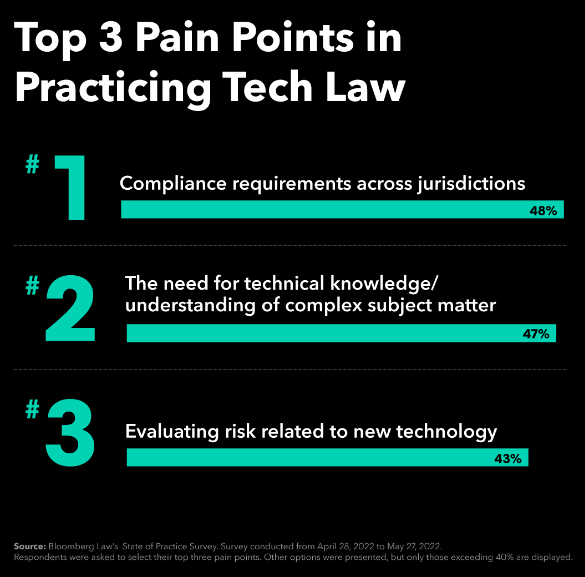

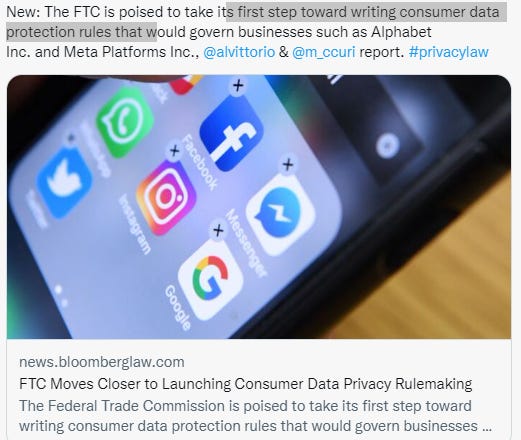

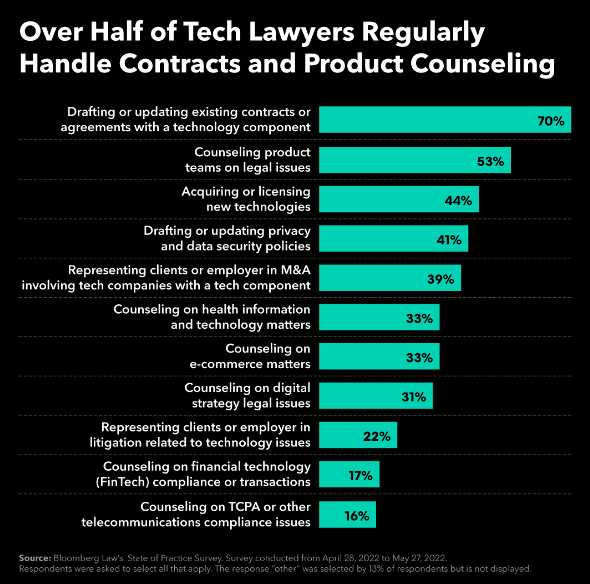

In U.S., as someone who gets a headache just *thinking* about IP (Intellectual Property), it’s a perfect demonstration of how the law — or lack of it — impacts real people. With virtual reality gaming and other metaverse applications going mainstream, digital goods modeled after real-life counterparts take on new significance, and lawyers and courts must grapple with how to apply IP law to the technology. The FTC is seeking public feedback on a proposed rulemaking to limit what it’s dubbed “commercial surveillance” by businesses that sell or share information collected about people. FTC also poised to take its first step toward writing consumer data protection rules that would govern businesses such as Alphabet Inc. and Meta Platforms Inc. Tech Companies are starting to face legal and financial consequences for their alleged use of dark patterns, deceptive website or app user interfaces used to trick or pressure consumers into making choices they otherwise might not. The latest version of the American Data Privacy and Protection Act would permit the California Privacy Protection Agency to enforce the new federal law just as it would the #CCPA--which would be preempted if this #ADPPA bill is passed.

In Europe, The EU is figuring out how #GDPR's right to be forgotten can be squared away with blockchain tech that never forgets. The fact that some consumers were able to trace their data to the dark web may have sped up this data breach settlement. To properly enforce its new DMA and DSA, the EU must recruit "more who want to work for the common good rather than the good snacks at Meta’s offices." The latest in EU, (Aug. 17th), Belgium’s YouTube stars, like Nathan Acid and Average Rob have declared war to their government, claiming new transparency rules will endanger their privacy. Tech policy governing influencers needs to be smart: Content creators often work as a private person & develop their activities out of their home. Transparency requirements in Belgium is at odds with respecting their privacy.

==========

(Spesifik PSE pada Juli 2022)

00.21 WIT 20 Juli 2022.

*kebiasaan pemerintah NKRI masih selalu membuat toleransi / undur batas waktu

1 Maret 2022. Di kantor SEA Group untuk cabang Jakarta (bukan Singapura). “Ekosistem digital yang kondusif harus kita bangun bersama-sama” = ajakan agar jika ada unit SEA yang belum terdaftar, agar didaftarkan. SEA Group juga memiliki Garena, salah satu pemain bisnis eSports terbesar dunia)

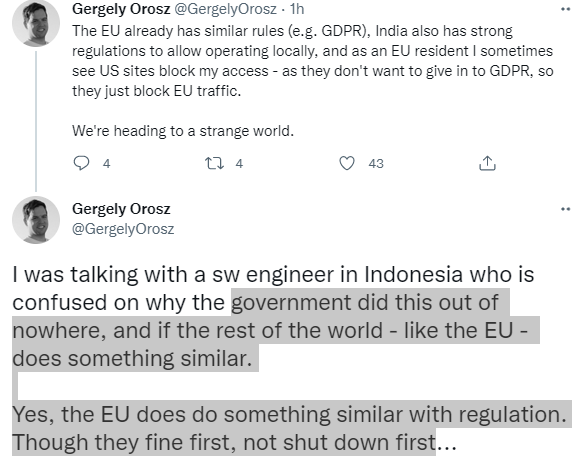

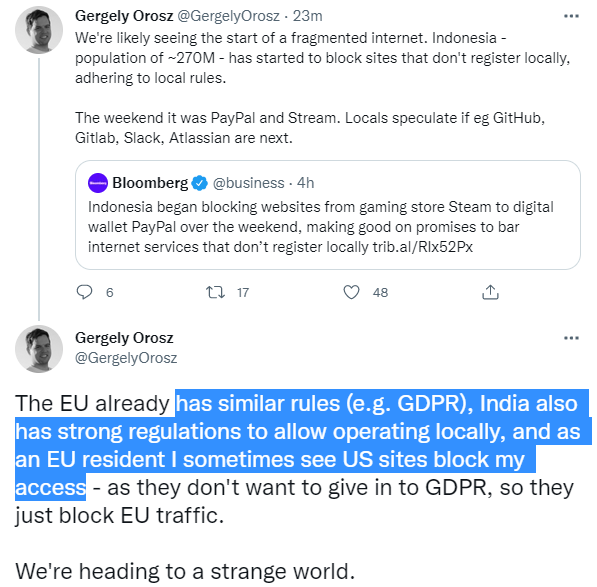

Kalau benar-benar kebijakan amat paksa, yang sebetulnya bisa dilakukan minimal sejak 2010, tapi baru dilakukan, cuma gara-gara Mas Dedy, it’s wow. Pemaksaan PSE terdaftar ini ya hal lumrah seperti perkelahian Uni Eropa dengan semua Big Tech (“anda bisa googling “VESTAGER”, “Digital Service Act”; “Digital Market Act”, atau seperti saya: langganan POLITICO EUROPE).

*80 jam setelah diblokir di Indonesia, PayPal berencana lebih banyak merekrut Engineer negara berkembang/Engineer domisili negara dengan kebijakan upah terjangkau

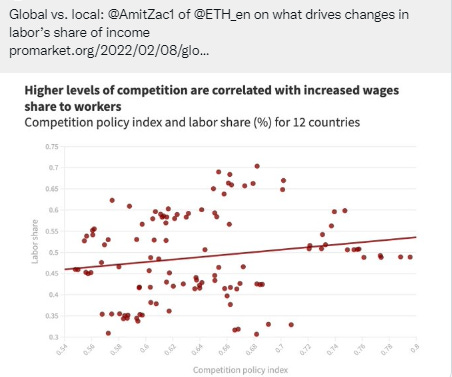

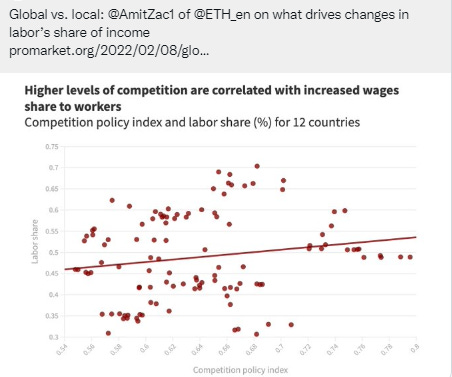

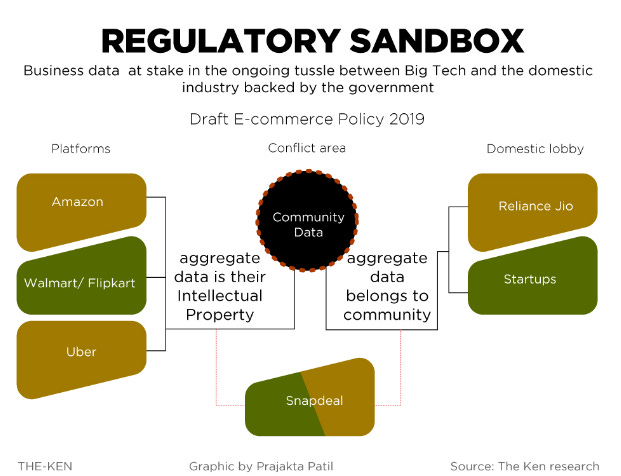

Orang marah-marah karena (berasumsi) dengan semakin diatur, PSE akan (dipaksa) mengeluarkan dana tambahan dan (kemudian)pelanggan atas PSE akan (potensial) terkenal dana tambahan yang lebih besar. Itulah satu hal asumsi yang diunggah/disuarakan dalam 5 hari terakhir. Kenyataannya, di UE, saat “more regulated”, PSE setempat diatur, justru bisa dipaksa memberikan harga lebih murah aats service kepada konsumen. “Reducing costs elsewhere”.

Berbagai perusahaan atau PSE atau lembaga yang menjadi target Kominfo (*akhirnya diblokir) patuh atas GDPR-DSA-DMA di UE, atau aturan sejenis di Amerika, India, Kanada, UK, Jepang, China bahkan, dll.

Berita diskriminasi PayPal kepada Palestina ditulis 7 Juni 2022, bukan dadakan ditulis, dan yang menulis pun kantor media Israel. Berita “Mafia PayPal” ditulis 13 Juni 2019, dan bukan dadakan ditulis.

Saya ga sama sekali bermaksud membela “pamarenta NKRI—-dengan segala kerumitan administrasi dan birokrasi ultra kacau”. Tapi regulasi memaksa PSE agar terdaftar, itu lumrah banget.

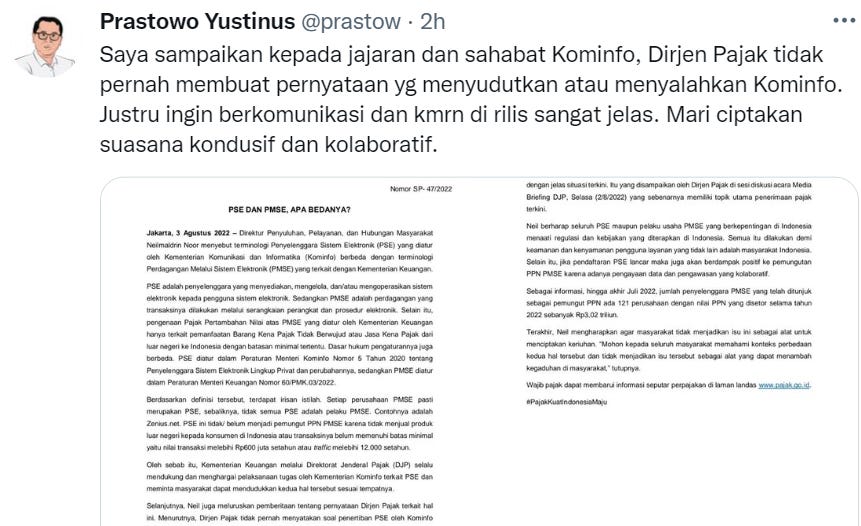

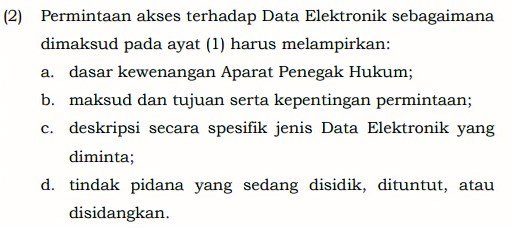

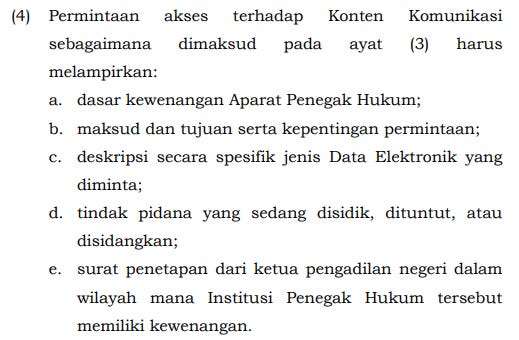

*Akses konten data media sosial pasca penertiban PSE:

harus disertai dokumen / harus lampirkan dasar kewenangan aparat hukum

*penataan PSE di Eropa bisa diarahkan “lokalisasi”, kewajiban meningkatkan investasi di tingkat lokal, diharuskan kepada PSE / Big Tech. Respon kurang dari 100 jam dari PayPal bahwa PayPal berkomitmen “lebih banyak merekrut engineer negara-negara lebih murah gaji” (artinya Indonesia potensial) menandakan jika PSE dipaksa untuk diatur, mereka sebetulnya mau dan bisa untuk meningkatkan kontribusi pada lokal.

Di tengah “omong-omong” NGO sejak lama sekali, dan saya sudah terlibat bahkan sejak 2009an, Pak Semmy Pangerapan (Kominfo) semacam “penengah” antara NGO NGO yang memang sangat pro keterbukaan publik dll, dengan pihak pemerintah. Dengan masuknya Pak Semmy, eks NGO, sejak dekade lalu, NGO punya “orang yang paham” keluhan para pihak NGO—karena Pak Semmy pun orang NGO sebelum masuk kominfo sejak dekade lalu. “Backchannel” atau apalah istilahnya, langsung pada pemerintah. Meski tentu ga setinggi Mas Raja Antoni (aktivis, kini Wakil Menteri Pertanahan). Tapi dari dekade lalu sampai sekarang, Pak Semmy posisinya ga berubah dan sudah sangat sentral.

*digital gatekeeper rules = penataan PSE

Maka, saya sebetulnya bingung mengapa tidak dari dulu pemaksaan agar semua PSE (Penyelenggara Sistem Elektronik) patuh untuk terdaftar dilakukan sejak dekade lalu saat Pak Semmy sudah masuk Kominfo (sejak lama).

=======

India: Contoh Regulasi Penataan PSE atau apapun istilah setempat, antara 2019 vs kebijakan terbaru PM Narendra Modi

Menurut netihen, NKRI sangat buruk IT nya dan "tipu-tipu", startup nya sebetulnya bikinan India (Bangalore / Bengaluru)

Netihen yang sama:

Kominfo serem banget doxing, surveillance (*buktinya apa???)

Jadi Indonesia itu secluded, super terbelakang, atau super canggih seperti (utamanya) China dalam surveillance, U.S., EU?

Jadi ahli-ahli IT Indonesia, pasca penataan PSE, sebaiknya pindah ke negara lain, yg aturan seperti "menata PSE" jauh lebih brutal, strictly dibanding +62?

Gimana Gimana?

*spectrum / frequency in India

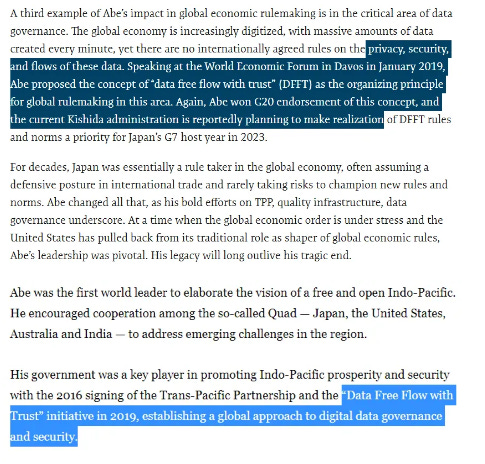

*debat penataan PSE di India. Oktober 2019. India, bersama Indonesia, dalam G20, menolak Data Free Flow usulan lama dari mendiang Abe Shinzo. PM Kishida berjanji melakukan segala cara agar semua anggota G20 setuju Data Free Flow sebagai penghormatan pada Abe Shinzo, entah pada G20 saat presidensi Indonesia atau kesempatan lain. Tahun depan: India. India (harusnya tahun ini) dan Indonesia sepakat bertukar tahun presidensi saat G20 2021 di Roma, karena Indonesia merasa sulit jika memegang Presidensi G20 dan ASEAN bersamaan/tahun yang sama. 2023, Indonesia Presidensi ASEAN

================

ESO/Electronic Service Operators —- PSE / Penyelenggara Sistem Elektronik

Kecuali, bahwa seorang HI (UGM) — paham sekali isu-isu internasional, meng-insinuasi, persuasi Pak Semmy, dan terjadilah pemaksaan terhadap PSE. mungkin. Mungkin itulah yang dilakukan Mas Dedy.

Kominfo kurang HI banget. Saya pernah dengan secara vulgar menulis bahwa ketidaktahuan Pak Plate akan jurusan HI yang mungkin membuat Pak Plate memilih Maudy Ayunda — bahkan disaat Mas Dedy anak HI.

Tapi ini selalu perkiraan aja.

salah satu agak mirip-mirip penerapan sama rata PSE/Penyelenggara Sistem Elektronik di India. Sempat free/gratis, tapi kemudian harus bayar. “Pay your tax now (in) here”, jika terdaftar resmi, ya harus bayar ke pemerintah. Bukan semata berbisnis lalu tidak bayar apapun ke pemerintah {India}

India, kita kenal amat jago IT, 35% CEO atas perusahaan IT sedunia “berdarah / keturunan India (bahkan bentar lagi ada PM Inggris dari India—jika beruntung), sudah memaksakan regulasi PSE ini sejak lama banget. Kalau anda punya kepastian kantor “big tech” terdaftar resmi di pemerintah, logikanya, karir IT anda bisa jauh lebih “termaknai hukum”. Atau: pemerintah (setempat/dimaksud) lebih bisa mengejar tanggungjawab IT-IT dimaksud jika berbuat ulah atau platform online-nya dipakai untuk kejahatan.

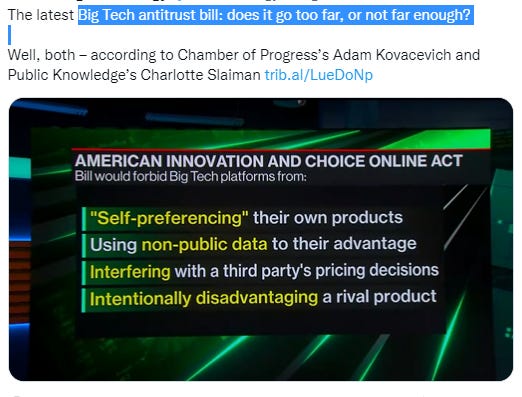

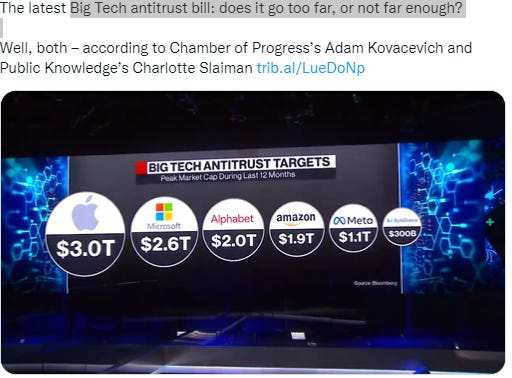

*di Amerika, seperti (level) di Uni Eropa, pengaturan Big Tech sudah pada level bukan semata menata, atau mencegah monopoli yang timpang, tapi “antitrust yang sangat kompleks, amat ketat”

antitrust research: clik here

Inilah mengapa India jauh lebih unggul dalam penindakan kejahatan online, dengan beban populasi yang 1,4-1,5 miliar jiwa, 5x NKRI padahal. Atau, jika CEO suatu IT global adalah keturunan India, kecenderungannya bahwa perusahaan IT tersebut lebih patuh hukum dan atau lebih brutal mencegah penyalahgunaan online.

Tamsil/pengandaian paling sederhana yang saya temui terkait PSE:

Perkelahian Twitter vs Elon Musk misalnya, dimana kecederungan Elon Musk (jika jadi membeli—-dan akhirnya batal dan malah bersengketa hukum) akan membuat Twitter ultra vulgar kebabalasan online, “dianggap” bahwa CEO Twitter, Parag Agrawal, keturunan India, mencegah betul Twitter “kebablasan”—-bahkan ga masalah harus berhadapan dengan orang terkaya nomor 1/nomor 2 dunia.

Apalagi Uni Eropa, dimana perkelahian UE dan Big Tech selalu disimbolkan dengan satu nama petinggi UE: Vestager.

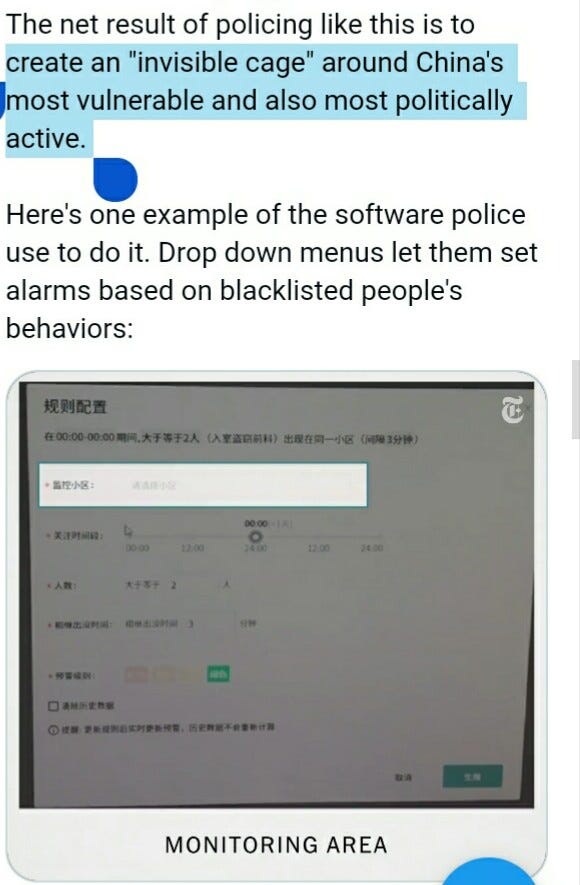

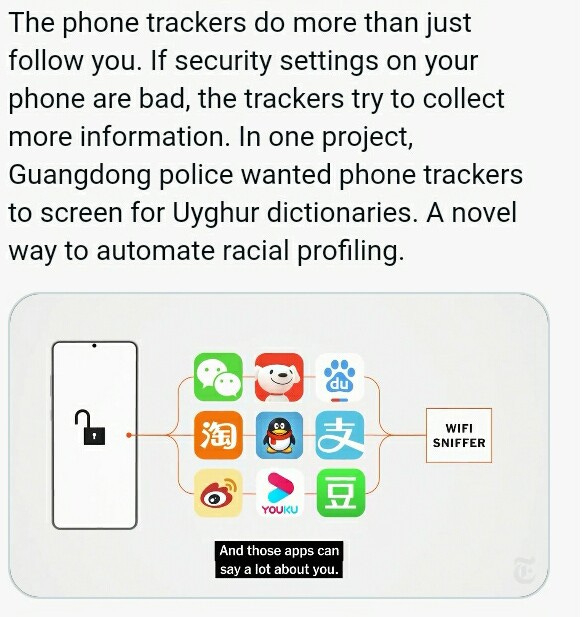

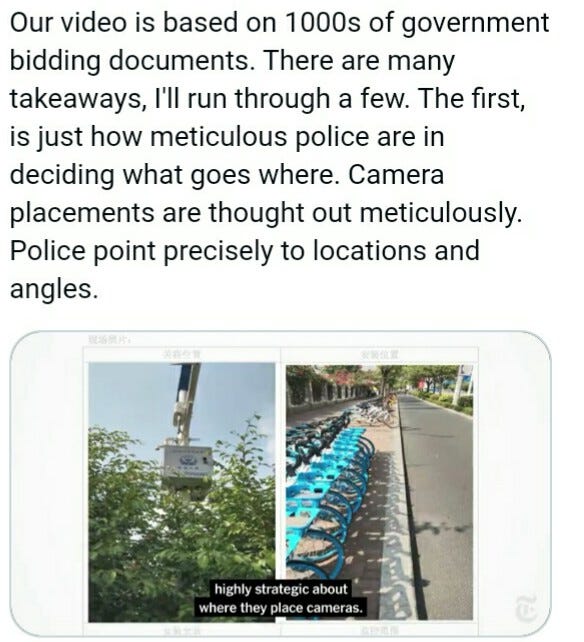

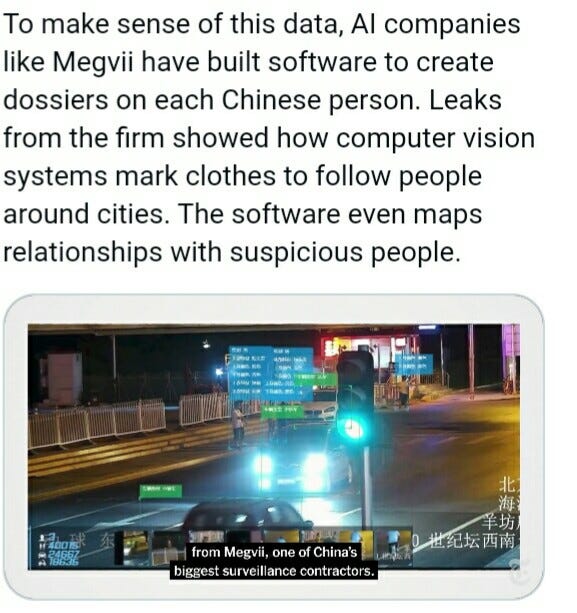

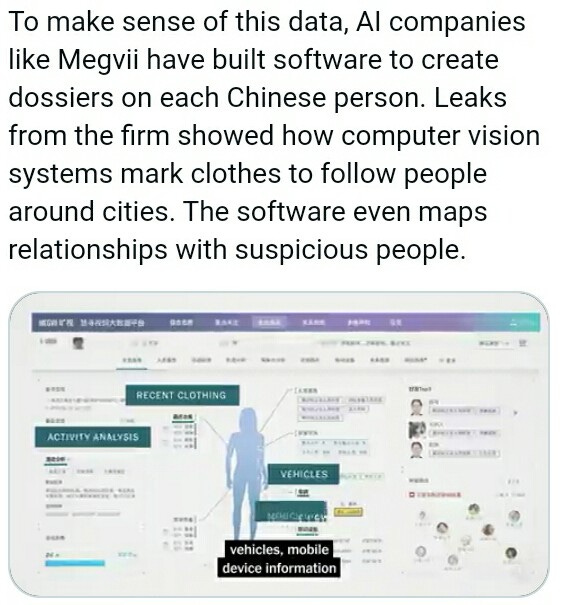

Orang Barat mengistilahkan “Orwellian”. Saya ga bisa memasukkan kasuistik China (yang lebih brutal lagi keharusan pendaftaran hukum dll), karena surveillance di China lebih sinting. Beban populasi yang brutal mendorong surveillance yang “ultra” brutal di China. Indonesia ga jadi negara “mata-mata” koq, murni regulasi penertiban agar ditata, terdaftar. Simpel. Lumrah. Dari all negara dengan penduduk diatas 100 juta, Indonesia negara yang kedua paling rendah surveillance pada warganya sendiri. Paling lemah Bangladesh.

*Sandiaga bukan semata Menparekraf, “EKONOMI KREATIF”. tapi juga Dewan Pembina eSports Indonesia. Dia pemegang CFA di eranya dan saat itu masih jarang sekali {*bisa cek YouTube Sandiaga - Gita Wirjawan}, “di Indonesia saat itu CFA itu dibatasi kuotanya”. Sandi tahu hitung-hitungan potensi eSports. Maka dicatat ulang (*penertiban, PSE diminta mendaftar), biar lebih dicatat rapi. Tapi potensi kemungkinan terlanjur hilang/tidak masuk pemasukan negara (PSE tidak kunjung mendaftar), yang lebih paham Menkeu Sri Mulyani

Sebetulnya dengan pemaksaan PSE di Indonesia ini, yang saya duga kuat karena ide HI UGM bernama Mas Dedy, orang2 yang ketakutan ya (salah satunya) hewan2 peliharaannya Wulan di HI UGM yang suka melakukan kejahatan online.

Sayang banget ya Wulan (/ Nindy - Mas Tanto, yang jelas jelas sudah di Kemenpar) ga berani melakukan perubahan radikal seperti ini. Mas Dedy, or Pak Semmy, ga gentar melawan perusahaan IT manapun. Sepertu Vestager ga gentar diteror lobi-lobi Big Teh di Uni Eropa. Tapi Wulan memang starap yang pindah entah kemana. Apa yang dia tinggal pun sedang berdarah-darah, bingung mau IPO saat perusahaan sejenis melakukan IPO malah limbung. Apa Wulan ga niat masuk pemerintah aja kali ya. Di swasta (startup) yang lebih flexible aja gabisa mengubah apa-apa, apalagi di pemerintahan yang serumit itu birokrasi memuakkan. Tapi memang ga sanggup memperbaiki apa-apa, ga becus pula.

That’s life. That’s karma

2.51 WIT 21 Juli.

end

====

Sudah 67 jam 22 menitan dari aturan blokir, tapi Kaesang tidak marah-marah di Twitter. Pak Plate pasti ngomong dulu bukan hanya ke Jokowi tapi bahkan ke Kaesang (literal punya bisnis eSports) kalau bisnis ini terdampak regulasi sama rata ke semua PSE (Penyelenggara Sistem Elektronik). Jamak sekali Menteri lebih takut Presiden or keluarganya.

*ditulis dari orang yang bahkan sudah aktif “bersentuhan langsung” dengan NGO sejak 2006—sebelum masuk kuliah