Scholz's Trauma about Nuclear

Nukes help us avoid the harder path, diplomacy. Allies can count on Germany to drag its feet, parse every decision and then play the “beleidigte Leberwurst” (an offended liver sausage).

Bundeskanzler, Chancellor Olaf Scholz himself explain about weapons deliveries by pointing to people’s anxiety about nuclear war & stating that he will do everything to prevent it. While not explicitly saying that “heavy weapons will Lead to nuclear war“, we know from framing studies that it is important what people understand, not what is said.

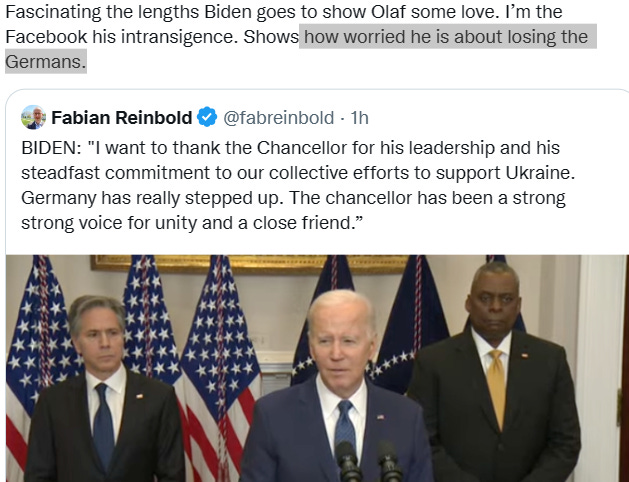

Why is Olaf Scholz hesitating to send tanks to Ukraine due to Russia's nuclear threats? I thought he already sorted that part out on his trip to Beijing (6 days before the G20 Summit in Indonesia, specifically Bali), which he justified by the guarantee he got that China would oppose the use of nukes. Amidst preventing nuclear war together with China and try to mediate between Russia (China’s side) and the West (Germany side), Olaf Scholz racked up gargantuan business contracts with China, especially Airbus.

Scholz statement made headlines & was often presented as weapons will lead to . This campaign effectively broke Germans cautious support for heavy weapons. Olaf Scholz takes decisions “de facto” alone on tank deliveries and believes the US as nuclear power on par with Russia is needed as reinsurance. The Chancellery's (Scholz's) demands, and rationale seem to be based on halfbaked strategic thinking. As if there was no nuclear umbrella provided by the US already, no NATO Article 5 guarantee and no joint European-American effort to equip Ukraine with modern weapons together - all sharing any associated risk. And as if there was a lack of knowledge and underststanding of how deterrence works - or a lack of trust in allies. Both would be worrying.

Olaf Scholz made a “fairly reasonable” request because Germany relies on the U.S. for a nuclear deterrent and “are much closer to this fight than we are.” Germany abandoning its historic responsibility after WW2 is what held Scholz back from exporting weapons earlier. If Germany had its own nuclear umbrella or one that doesn’t involve the US and sufficient other military deterrence capabilities, Scholz may not have reached out to the US to provide extra cover and maximum reinsurance. The logic of nuclear weapons is that no one wants to start a war if you’ve got one. So why not give them to everyone?

Olaf Scholz’s long dithering before sending tanks is symptomatic of a deep-seated mindset that détente won the Cold War, not Reagan’s belligerence. Scholz’s fear of nuclear escalation and Russian retaliation and distrust of deterrence without direct US involvement. If correct, and it does seem highly likely, then Scholz‘s strategic calculus is deeply worrying as it remains stuck in the 1980s without any true desire to lead on weapons. In their meetings with the East German officials, Scholz’s group called on the USSR to respond in kind by 'putting something on America’s doorstep,' include nuclear weapons, because the Soviet missiles pointed at Europe 'were not an adequate threat to the U.S.A.'" Germany after WW2 faced off between Jupiter or Pershing in NATO side vs R-12 Dvina and R-14 Chusovaya in Sovyet side.

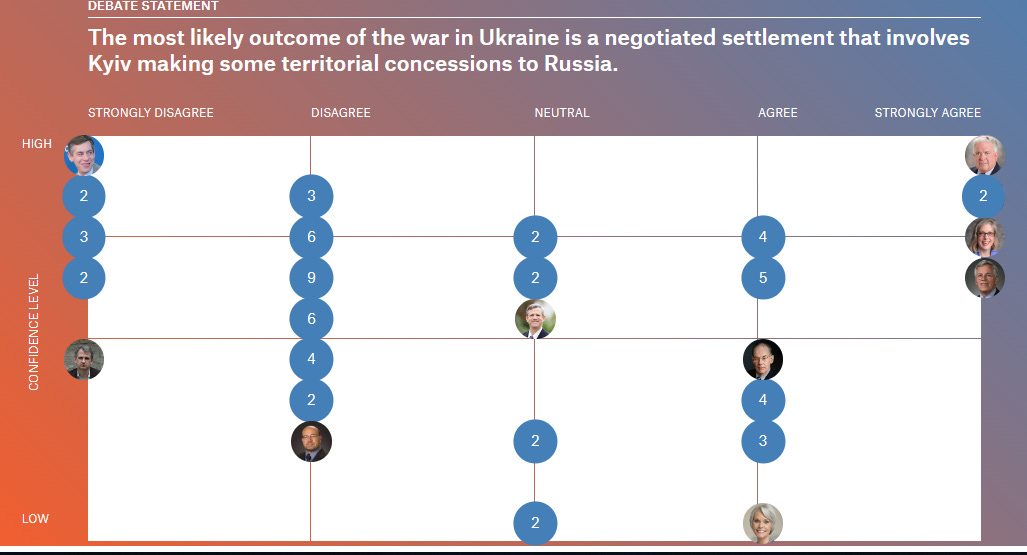

Scholz is thinking along the same lines with John Mearsheimer who suggests that a possible failure might lead Russia to use nuclear weapons which would naturally be disastrous for Europe.

In the Bundestag, 78 years after WW2, the Chancellor castigated those who believed in the spring that decoupling from Russian energy would lead to an economic crisis. It was Scholz who painted this nightmare on the wall to prevent far-reaching energy sanctions against Russia. The cynicism (and anti-US hostility) behind Germany's supposedly conscience-stricken stance on things, where other analyses are still too credulous. Made a “fairly reasonable” request because Germany relies on the U.S. for a nuclear deterrent and “are much closer to this fight.”

Extended deterrence Problem. Wie glaubwürdig sind Sicherheitsgarantien, wenn der Konflikt auf Europa begrenzt bleibt.

Since last December, before Christmas 2022, the United States has begun to replace its nuclear weapons on European soil with more modern ones. It is replacing the B61-3, B61-4 and B61-7 thermonuclear bombs with the B61-12, which has become the main US and NATO air-launched nuclear weapon.

It is a free-fall bomb equipped with state-of-the-art navigation systems and a versatile warhead that can be configured in four strengths, 0.3 kiloton (kt), 1.5 kt, 10 kt and 50 kt depending on the target, making it a low to medium-yield weapon. This type of weapon is referred to as a ‘first-strike’ weapon. Having a tactical nuclear weapon with higher precision and lower yield could make politicians less reluctant to use them in conventional operations and puts us on an increasingly dangerous front line of confrontation between NATO and Russia.

These new nuclear weapons will replace existing ones on the soil of Belgium (Kleine Brogel, maybe 20 nuclear weapons), the Netherlands (Volkel, also 20), Italy (2 places, in Aviano and in Ghedi, also 20 - 20), Germany (Büchel, also 20) and Turkiye (Incirlik, also 20). But Washington has announced that it will also deploy them on UK soil; this time it is not a replacement for more outdated ones, as it reported in 2008 that its nuclear weapons had been withdrawn from the RAF; now it appears that it wants to put new nuclear weapons in the empty bunkers at Lakenheath again.

All this deployment of nuclear weapons represents a violation of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). The NPT prohibits nuclear-weapon States Parties from transferring nuclear weapons to any other State and prohibits non-nuclear-weapon States Parties from receiving nuclear weapons or from manufacturing or acquiring them.

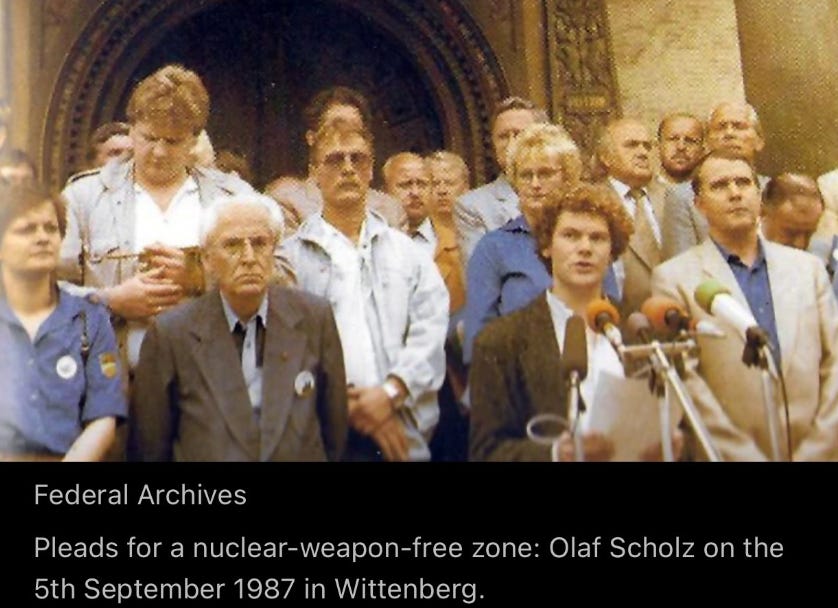

In early January of 1984, an aspiring young West German socialist with a shoulder-length curly mane traveled by train to East Berlin with his comrades for an important meeting.

It was a tense time in the Cold War with the arms race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union at a fever pitch. Even so, the young man’s entourage was welcomed with open arms and even spared the rigors of East Germany’s border guards; after all, he was a friend.

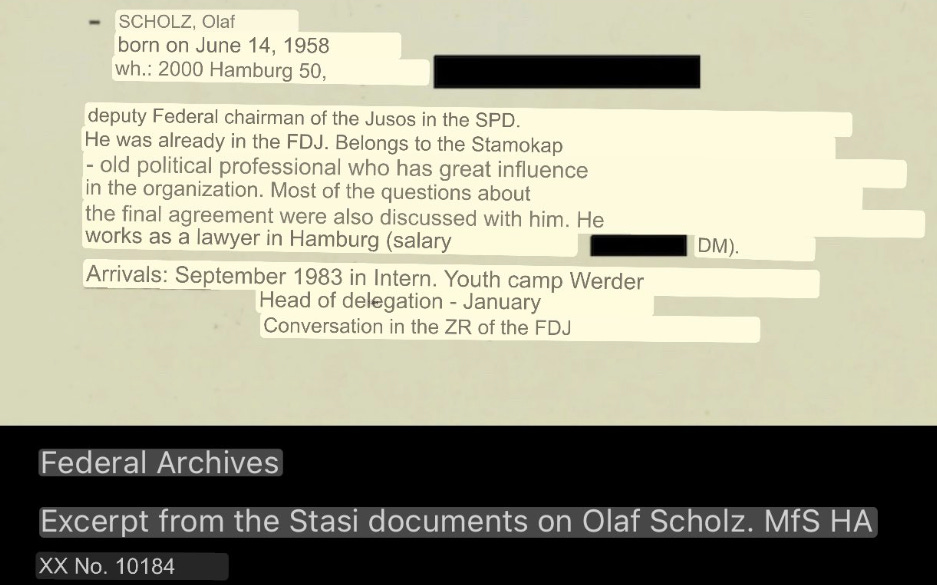

At the meeting between the young socialists and East Germany’s communist leadership, the young man, a Hamburg law student in his mid-20s named Olaf Scholz, could be seen sitting directly across from Egon Krenz, the protégé of East German leader Erich Honecker.

Details of the visit featured prominently on East Germany’s main TV news program and the next day it was front-page news in Neues Deutschland, the communist regime’s newspaper.

In the early 1980s, Scholz and the communists shared a common goal: to block the U.S. from stationing mid-range nuclear missiles in Europe. The U.S. plans, triggered by a similar step from the Soviets, had unleashed some of the largest and most violent protests West Germany had seen in decades. The organizers of the protests, including Scholz, who was then a deputy leader of the socialist youth movement, viewed then-U.S. President Ronald Reagan as a loose cannon and worried he might start a nuclear war.

In their meetings with the East German officials, Scholz’s group called on the USSR to respond in kind by “putting something on America’s doorstep,” i.e. nuclear weapons, because the Soviet missiles pointed at Europe “were not an adequate threat to the U.S.A.,” according to a detailed report on the visit complied by East Germany’s Stasi secret police.

Throughout the 1980s, Scholz made at least nine trips to the DDR, according to the records, including a 1986 visit to Krenz, who succeeded Honecker as East Germany’s leader shortly before the fall of the Berlin Wall. (In 1997, Krenz was convicted of manslaughter in four cases connected to the killing of East Germans trying to flee the country.)

Scholz, who was finance minister in Angela Merkel’s last government before succeeding her as chancellor at the end of 2021, has largely dodged questions about his dealings in East Germany. Scholz was born on 14 June 1958, in Osnabrück, Lower Saxony, but grew up in Hamburg's Rahlstedt district. Too far from the Berlin wall or DDR.

Yet there are strong echoes between Scholz’s steadfast refusal to take a more resolute stance on Russia over Ukraine and his youthful enthusiasm for socialism and the Soviet-led sphere which was accompanied by fervent anti-Americanism.

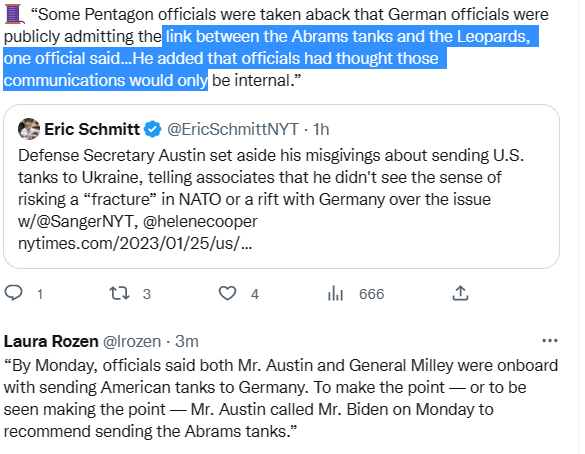

After months of stubborn resistance, Scholz has cleared the way for Germany and other countries that own German-made Leopard tanks to send them to Ukraine, in same date that Zelenskyy's birthday (Jan 25th, 2023). As welcome as his about-face is, it comes only after Scholz triggered a massive row both within NATO and in his own German coalition over the issue.

For Scholz and his cohorts in the 1980s, the communists were allies and NATO the aggressor. Scholz, who was regarded as a leftist within the Social Democratic Party, pushed his party to consider a West German exit from NATO, which he characterized as “aggressive and imperial.”

Scholz not alone. not alone. Rolf Mützenich, the leader of Scholz’s Social Democrats in the German parliament who came of age at the same time as the chancellor, has spent decades trying to rid Germany of American nuclear weapons. Amid the tank debate, he played a crucial role in playing defense for his old comrade.

The Scholz-Mützenich approach to Vladimir Putin’s Russia is rooted in the prevailing German narrative about what ended the Cold War and led to reunification. In the German mind, it was Ostpolitik, the détente policies introduced by Chancellor Willy Brandt in the early 1970s. It was Germany’s engagement with the Soviets, both economic and diplomatic, that led to a peaceful end to the Cold War and not Reagan’s belligerence.

That view is not just at odds with America’s historical understanding of the period, it also runs counter to what most eastern Europeans believe. For Poland, it was the courage of the Solidarity movement to stand up to their communist masters that ushered in change, for example.

Yet Germany’s perception of how and why the Cold War ended has become its reality and informs both policy-making and public opinion. Remember ex-Chancellor Merkel’s years-long insistence on pursuing fruitless “dialogue” with Putin instead of standing up to him?

Scholz too has shown that the only thing allies can count on Germany for is that it will drag its feet, parse every decision large or small and then play what Germans like to call a “beleidigte Leberwurst” (an offended liver sausage), demanding more “respect.”

Yes, Scholz is now willing to send Ukraine tanks, but only after a year of pressure and in numbers (14 in total) that leave something to be desired.

Putin’s erstwhile socialist comrades in Berlin may not be willing to ignore the atrocities he has committed in Ukraine, but as the German chancellor has proved over the past year, the Russian leader can at the very least count on them to buy him more time. Scholz’s spinmeisters are now declaring “All’s well that ends well.” That may provide some comfort to the chancellor and his inner circle.

But considering the daily carnage Ukrainian forces face on the front lines as a result of the delays, it shouldn’t.

The fear of nuclear escalation from Russia seems to run so deep with Scholz that he is unwilling to move without an iron-clad guarantee from the US, i.e. German Leopard 2s only together with M1 Abrams. As some others also have pointed out, this shows a good deal of distrust in Until in (coincidence) Zelenskyy birthday, Jan 25th, Scholz give a green light about Leopard.

Peace is our profession,” General John E. Hyten told a crowd at the Mitchell Institute over breakfast in 2017. Hyten was then the commander of United States Strategic Command (STRATCOM)—a division of the American military in charge of its nuclear arsenal—and as surprising as it may sound, he was repeating its motto.

“Can I imagine a world without nuclear weapons?” Hyten went on to ask. “I can easily imagine a world without nuclear weapons because I know what it looks like. Because we had a world without nuclear weapons for most of our existence. And all you have to do to know what a world without nuclear weapons looks like is go back to the period before August of 1945. Just go back and think about what the history books say.”

Hyten explained to the Mitchell Institute crowd, a group of retired Air Force officers turned think tank wonks, that the six years prior to the dropping of the nuclear bomb on Nagasaki were some of the bloodiest in world history. “World War II killed somewhere between 60 and 80 million people,” he said. “Take our experience in Vietnam. A horrible experience in Vietnam where we lost 58,000 of America’s greatest heroes, 58,000 of our greatest gifts, our sons and daughters, in our experience over the, over a decade-long experience in Vietnam. Less than two days of World War II.”

In Hyten’s eyes, that smaller body count was a gift from an unpredictable source: nuclear weapons. “That’s what nuclear weapons have done for the world,” he said. “It does not eliminate conflict. Conflict will exist as long as humans exist. But what it has done is it has kept major power conflict off the world stages. It’s kept that huge death and destruction from happening when you have major power conflicts that get out of control. It’s kept world wars from happening. That’s the primary reason why we have to have nuclear weapons.”

If what Hyten says is true, why not take it to its furthest conclusion: What if every country in the world had a nuclear bomb? It’s a question so farcical on its face that the mind rejects it, but it’s also an important one that exposes the cruel logic of nuclear weapons for the absurdity that it is.

More weapons don’t mean more peace. Nuclear weapons are a promise and eventually, either by accident or in anger, someone will launch one. The mass proliferation of these weapons is a way to ensure we see a nuclear detonation in our lifetime—not a path to peace, but a political tool meant to keep the world in line through fear and intimidation. The only good thing about this unthinkable idea is that it makes us face the cold reality of nuclear weapons, and the uncomfortably high odds that they’ll kill us all one day.

The idea of mass proliferation has a long and storied history, and to understand it, you need to understand how the U.S. military views nuclear weapons. For 75 years, it’s been telling the world that nukes make the world a safer place.

This is certainly a take, but it’s not especially convincing to experts who study nuclear weapons. “If you actually believe that, then why would nuclear weapons provide security for the United States but not all other countries?” said Jeffrey Lewis, director of the East Asia Nonproliferation Project at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies. “What [STRATCOM] really means is ‘Well, we want nuclear weapons but we don’t want anyone else to have them.’”

Following STRATCOM logic, more nuclear bombs would mean more peace. If that’s the case, then why not just give every nation nuclear bombs?

“It’s such an important question because the objections to giving every country nuclear weapons illustrate the long-term danger of relying on nuclear deterrence for our security,” Lewis says. “I actually think that people who say more nuclear weapons would reduce war are probably right. But there’s a problem.”

To understand the problem, we have to understand deterrence. America’s nuclear weapons infrastructure operates on a triad. It has intercontinental ballistic missiles, submarine-launched nukes, and strategic bombers ready to drop a city-ender. The point of these weapons is to deter anyone from fucking with the United States. They are an implicit promise: attack us or launch a nuclear strike and we will end you.

“Nuclear deterrence is the bedrock of U.S. national security,” David Trachtenberg, deputy undersecretary of defense for policy, told the House Armed Services Committee in 2019. “Our nuclear deterrent underwrites all U.S. military operations and diplomacy across the globe. It is the backstop and foundation of our national defense.” But Trachtenberg added a key detail: “A strong nuclear deterrent also contributes to U.S. non-proliferation goals by limiting the incentive for allies to have their own nuclear weapons.”

According to its adherents, deterrence keeps the world safer. Who would risk total war with a nuclear power? The problem is that, on a long enough timeline, it’s inevitable that a nuclear weapon is going to detonate, for one reason or another. “The expectation that nuclear deterrence will function perfectly, forever, seems very unrealistic,” Lewis said. “If you believe, at some point, that it will fail, then you have to put on the chart the casualties from that war.”

More nuclear weapons in the hands of more countries means more fingers on the button. It means more chances for accidents and more nukes in unstable parts of the world. If that makes your blood run cold, rather than giving you a sense of comfort, that’s the point. “It makes the nature of the risk we’re taking extremely clear,” Lewis said. “We are unwilling to do the hard work of using diplomacy to avoid war. So we have made this Faustian bargain with the bomb that it will keep us safe for some unknown period of time before it murders us all. Technology eventually fails. I don’t want to be on Earth for the once in-a-lifetime deterrence failure.”

Nine countries have nuclear weapons: The U.S., Russia’s Putin, the United Kingdom, France, Israel, India, Pakistan, China, and North Korea’s Kim Jong-un. According to the Arms Control Association, that’s a combined total of 13,500 warheads, more than 90 percent of which belong to Russia and the U.S. Until recently, the world had made good progress in dismantling these warheads, but recent tensions between the U.S. and Russia have pushed both to develop new types of weapons, while North Korea getting the bomb has made Japan and South Korea reconsider their own access.

Not all non-nuclear weapon states are equal. Japan, Canada, Germany, and Australia aren’t nuclear powers but they do possess what experts call nuclear latency. If Japan wants nukes, it has the resources and the technology to build them. All it requires is the will; experts have estimated that Japan could have a nuclear weapon within six months of deciding to build one.

With so many countries close to having a nuke, why not just let them spread? “It’s an appropriate question to ask right now,” said Scott Sagan, senior fellow at the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford. “We’re facing a new set of states that are potentially on the cusp of acquiring nuclear weapons. Iran is the most obvious one, but Saudi Arabia if Iran goes forward. And the South Koreans and the Japanese are facing new domestic political pressures about the reliability of the American security guarantee.”

Sagan knows this debate well; he co-wrote the book on it. In The Spread of Nuclear Weapons: An Enduring Debate, first published in 1995, Sagan and co-author Kenneth Waltz, an academic who spent his life studying war and diplomacy, explained the basics of arms control and laid out their cases for and against proliferation.

Waltz died in 2013, but the debate continues, and his work endures. Very broadly, Sagan was against proliferation and Waltz was for it. Waltz was no fool; he’d thought deeply about the issue. His reasons were complicated, but boiled down to the idea that nuclear weapons are going to spread regardless of what we do, and so it’s best to take some control of the inevitable.

“The gradual spread of nuclear weapons is better than no spread and better than rapid spread,” he wrote in The Spread of Nuclear Weapons: More May Be Better in 1981. “We do not face a set of happy choices. We may prefer that countries have conventional weapons only, do not run arms races, and do not fight. Yet the alternative to nuclear weapons for some countries may be ruinous arms races with high risk of their becoming engaged in debilitating conventional wars.”

“His argument is that nuclear weapons are so horrific in their impact that any state would be deterred from not just using nuclear weapons, but by having any aggressive act because the risk of escalation would be too great,” Sagan said. “A group of us writing in the 1980s called this the crystal ball effect. There was an idea that if Kaiser Wilhelm had a crystal ball in 1918 that showed up the future, he would have been far more cautious. The idea that nuclear weapons automatically induce caution is what deterrence optimists like Waltz think.”

As Lewis said and many more have noted, though, the possession of nuclear weapons does not always end the wars or skirmishes between those who hold them. Violence and border disputes between India, China, and Pakistan persist to this day, and the Soviet Union and the U.S. almost came to nuclear blows repeatedly during the Cold War.

Worse, more nuclear weapons means more nuclear accidents. Before the U.S. developed the triad of ICBMs, SLBMs, and strategic bombers, it kept nuclear-armed bombers in the air above much of the world 24 hours a day and seven days a week. The idea was that, should the Soviet Union attack the U.S., the U.S. would be able to drop a nuclear bomb on a major city at a moment’s notice.

In practice, this meant amphetamine-addled fighter pilots circling the globe with world-destroying weapons strapped in the back of their bombers. There were accidents—a lot of them. In 1958, one of these bombers dropped a nuke on rural South Carolina. (Thankfully, it didn’t detonate.) Ten years later, and several accidents down the line, a B-52 carrying nukes crashed near Thule Air Base in Greenland. The nuke ruptured, spreading radioactive contamination into the ice. It was the latest in a long series of high-profile disasters and ended the practice of the U.S. flying nukes around the world.

Today, those weapons are still ready to go, but they sit in underground bunkers, on airfields, and under the ocean nestled in submarines. And mistakes persist. In 2007, the U.S. Air Force lost track of six live nukes for 36 hours. The nukes had been unwittingly loaded on to a B-52 and it was more than a day before anyone noticed the missiles had gone missing. More countries getting more nukes means more of these spread across the planet, exponentially increasing the amount of nuclear material out there and exponentially increasing the potential of another environmental disaster like what happened in Greenland.

Mass proliferation would also be an all-or-nothing game. If everyone gets nuclear weapons in the name of world peace, then some would have the weapons forced upon them against their will. “Not every country is going to want nukes,” says Martin Pfeiffer, a doctoral candidate in anthropology studying nuclear culture at the University of New Mexico. He pointed to Iran signaling it wants back into the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the Obama-era treaty that allows Iran to pursue nuclear reactors with international oversight that ensures it doesn’t develop nuclear weapons; Sweden, which had a nuclear weapons program it abandoned in the 1970s; and South Africa, which had nuclear weapons but chose to give them up. Eighty-four countries in the U.N. have signed the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, a legally binding international agreement that bans nukes with the end goal of total elimination of the warheads.

Despite the supposed security they confer, nuclear weapons aren’t popular. And that’s without tackling the logistical concerns of mass proliferation. “Somebody’s gotta make these weapons,” Pfeiffer said. “And it’s gonna be really expensive.” Who would regulate the distribution of nuclear weapons? The United States? The International Atomic Energy Agency? Pfeiffer notes that, in a world where every country has nuclear weapons, then power would belong to those countries with the ability to produce more.