Reno Nevada 10.40pm

You can still find Ronald Dion “Ron” DeSantis who got Republican donors and media so excited, just a year ago. A source familiar with the campaign described clips of DeSantis, usually at press conferences he gave as governor of Florida, that went viral in Republican circles. “A reporter comes in and asks a question, and he just rips their heart out,” the source said.

4 Months ago, Twenty-four hours after appearing with Elon Musk to announce his campaign for president, Florida Governor Ronald Dion “Ron” DeSantis just signed a bill into law that will shield Musk's SpaceX and other private space companies from negligence lawsuits after an explosion or a crash. Both Elon and Ron are also skeptical about the coronavirus vaccine.

Currently, at least 7-13 Aug 2023

Weekly U.S. COVID update:

- New cases: 125,647 est.

- Average: 106,120 (+6,509)

- States reporting: 50/50

- In hospital: 8,571 (+584)

- In ICU: 1,272 (+139)

- New deaths: 592

- Average: 670 (+65)

The questions were often about DeSantis’s covid policies, and also sometimes about his aggressive stances against the teaching of race and gender topics in public schools or his perplexing war on Disney. In response, DeSantis generally took an impatient tone—the press, he seemed to suggest, was once again wasting everyone’s time. The source went on, “But those were situations where it was about Florida policies, which he knew like the back of his hand, where he could deploy his computer brain. And it was in front of a crowd that was going to applaud no matter what.” In every sense, the staffer said, “he was in total control of the situation.”

DeSantis was offering something in thin supply during the pandemic years: the impression of conservative mastery. Just forty-four years old, a former Little League World Series standout who had gone to Yale on the strength of his ninety-ninth-percentile S.A.T.s, DeSantis had taken a contrarian, laissez-faire position on covid. He didn’t endure the disastrous public-health outcomes that liberals had warned of.

Ron DeSantis is over his feud with Disney and has drastically slowed-down his attacks on what he has dubbed the 'corporate kingdom' as his campaign chugs forward.

The Florida Governor urged Walt Disney Co. CEO Bob Iger to drop the lawsuit against his administration claiming he engaged in political retaliation in the war that was sparked when former CEO Bob Chapek spoke out against his education policies.

Speaking with CNBC in an interview set to air in full Monday evening on Last Call, DeSantis said that he and his allies have 'basically moved on' from the fight with Disney.

'I would just say, go back to what you did well,' DeSantis said as the final word on the matter. 'I think it's going to be the right business decision, and all that.'

His political popularity boomed, and so did migration to Florida. It wasn’t surprising that this kind of figure would appeal most keenly to conservative élites: his gubernatorial campaign last year, effectively a covid victory lap, drew an astonishing two hundred million dollars in contributions from donors, and, in a four-month period just after the 2020 election, Fox News producers asked DeSantis to appear on the network more than a hundred and ten times.

DeSantis has always misused public funds for campaign style events but his imploding presidential bid coincides with a 58% increase in tax dollars being spent on his security. The Florida Department of Law Enforcement released an annual report on Tuesday that showed that the amount the state spent protecting the governor grew from $5.94 million in the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2022, to $9.41 million during the budget year that ended June 30 of this year. The report tracks spending on staffing as well as transportation costs paid for the security detail over a 12-month period.

The Florida Department of Law Enforcement is responsible for providing security to the governor, first lady Casey DeSantis and members of the governor’s family, as well as security on the grounds of the governor’s mansion located about a mile north of the state Capitol in Tallahassee.

Taxpayer

The jump in security costs for DeSantis were largely due to an increase in salary costs for those guarding the governor. That rose from $2.37 million in 2022 to $5.03 million in 2023. The report does not break out the number of those that are part of the governor’s detail or whether the increased salary costs were due to overtime expenses.

Officials with the state’s law enforcement agency are reticent to go into specifics about the governor’s protective services due to security concerns. Earlier this year, state legislators passed a new law that shielded most of DeSantis’ travel records even on trips he had previously taken.

But Jeremy Redfern, a spokesman for DeSantis, said that the higher costs were due to a need to increase security for the governor.

“By law, FDLE must provide protective services to the governor and the first family,” Redfern said in an email. “His record as the most effective conservative governor in American history has also earned him an elevated threat profile, and FDLE has increased the number of protective agents to ensure the governor and his family remain safe.”

Last fall, DeSantis traveled throughout the state as he ran for re-election. But he also made trips out of state, including making appearances on behalf of other Republican candidates for office such as Arizona gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake. After he won a second term in office, DeSantis embarked on a tour during the spring to promote his book that took him across the country. He did not officially declare for president until late May, but once he did, he started making regular stops in key early primary states.

The state report also includes a breakdown on how much is spent providing protective details for visiting dignitaries such as governors and other top officials from other states. The agency spent more than $457,000 in the past year providing security for out-of-state visitors and other types of dignitaries, a total that included more than $96,000 spent on security for the Republican Governors Association meeting held in Orlando last number.

The report also says that the Department of Law Enforcement spent more than $117,000 for DeSantis’ inauguration — which was also augmented by private security services paid by the Republican Party of Florida.

By the end of 2022, after DeSantis romped to reëlection in a midterm cycle in which Republicans underperformed and some of Trump’s preferred candidates flamed out, it seemed to G.O.P. pollsters that the DeSantis phenomenon was no longer just top-down. “Every stitch of data I had said they really liked him,” a pollster for an opposing Republican campaign told me.

Since the 2020 election, Sarah Longwell, a Republican pollster closely affiliated with the Never Trump movement, has been conducting frequent focus groups with Republicans who voted twice for Trump. This past winter, Longwell told me, “We started having to screen groups for Trump favorability to find people who even wanted Trump to run again. I can’t tell you how dominant DeSantis was in that moment, and how clear people were that it was time to move on.” Former Trump voters, Longwell said, “were very DeSantis curious. They just thought Trump had too much baggage. But the way they talked about DeSantis, which I found interesting, was that they would talk about him relative to Trump. They would say, ‘He’s Trump without the baggage,’ or ‘He’s Trump with a new fight,’ or ‘He’s Trump not on steroids.’ That was one of my favorites.”

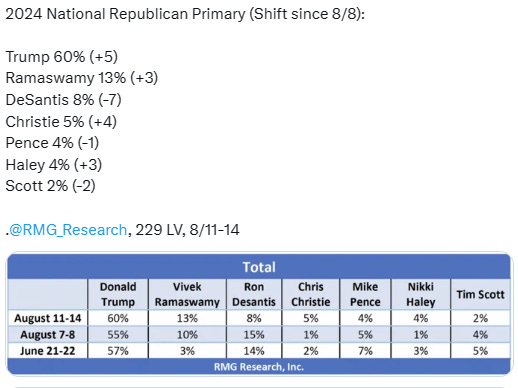

One theory circulating among politicos right now is that DeSantis simply waited too long to enter the race. He did not announce his candidacy formally until May, and did so in a clumsy and widely mocked Twitter Spaces event with Elon Musk. But, whatever the reasons for the delay, it was also the case that DeSantis and his advisers had not solved a fundamental problem for the campaign: how to run against Trump. Within two months of DeSantis’s announcement, his campaign laid off a third of its staff; last week, he fired his campaign manager. In a recent Times/Siena poll, he trailed Trump 54–17 among national Republican primary voters. “Trump Crushing DeSantis and G.O.P. Rivals,” the headline ran.

DeSantis offered no explanation for axing the energy programs in his veto message.

Asked why DeSantis did it, his press secretary, Jeremy Redfern said in an email that that the governor “reviews every bill and appropriation that comes across his desk and uses his authority under the Florida Constitution to veto bills that he believes are bad public policy.”

Five days after DeSantis vetoed the $30 million funding for energy programs that would have administered the federal rebates, the Office of Energy’s director sent letters to the U.S. Department of Energy withdrawing the state’s application to the program.

The U.S. Department of Energy sent out guidelines to state energy offices to set up energy efficiency rebate programs under the Rewiring America program, which is being financed under President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act and the Investment in Jobs Act.

“It gives states enough flexibility to design rebate programs that work for them while putting a priority on serving low- to moderate-income families who often spend the largest portion of their income on energy costs,” Rewiring America CEO Ari Matusiak said in a news release.

He said it was aimed at the households that are often hardest to keep comfortable in times of extreme temperatures, adding that the program would create 50,000 jobs.

It’s not the first time DeSantis has vetoed a budget item that would have helped reduce the use of gas or cut energy costs. He vetoed SB 284, a popular, bipartisan bill that would have allowed state agencies to increase the number of electric vehicles in their fleets, a measure that could have potentially saved the state $277 million.

It’s also not the first time DeSantis cut a program supported by Agriculture Commissioner Wilton Simpson. He vetoed a $100 million land to buy rural conservation easements from Florida farmers, which perplexed agricultural leaders across the state.

“There is no conceivable reason to target agriculture in a year when we have billions of dollars in reserves,” Simpson said at the time. “Agriculture was harmed today and so was the state of Florida.”

Cutting down energy costs is a top priority for her constituents, said state Rep. Anna Eskamani, a Democrat from Orlando. She and other members of the climate and energy legislative caucus recently met with U.S. Department of Energy officials to discuss other means of getting that money to Florida residents, but it doesn’t seem possible under the law.

“This is just another example of DeSantis choosing political ambition over the people of Florida,” Eskamani said. “It is not only foolish but it costs people money, especially now with the heat and peak energy usage.”

The U.S. DOE deadline for states to tap into those rebate funds is Jan. 31, 2025. So the Legislature could potentially reappropriate that seed money next session and reapply for the grants.

Milligan was equally perplexed about DeSantis turning down the $350 million. He compared it to former Gov. Rick Scott’s decision to pass on $1 billion from President Obama to build a high-speed rail from Orlando to Tampa. That money went to California and North Carolina instead.

“We should get a return on our tax dollars. This angers me a lot,” Milligan said. “DeSantis cut us off at the knees.”

Allison Rice was looking forward to using that program to help finance upgrades to her 52-year-old Winter Park home. She discovered the electrical wiring is outdated, so she’s been holding off on getting a new air conditioner, hot water heater, and new electrical wiring.

“I pretty much need everything that’s offered on this list,” Rice said.

The program would help preserve other older housing stock like hers, which would help maintain affordable housing, she said.

”We need to invest money in the existing neighborhoods like Azalea Park and Pine Hills,” Rice said, “not build new ones.”

Even before its official launch, the campaign and its allies were conducting polls and focus groups to test various anti-Trump messages. Across several months, the source familiar with the campaign said that it consistently struggled to find a message critical of Trump that resonated with rank-and-file Republican voters. Even attaching Trump’s name to an otherwise effective message had a tendency to invert the results, this source said. If a moderator said that the covid lockdowns destroyed small businesses and facilitated the largest upward wealth transfer in modern American history, seventy per cent of the Republicans surveyed would agree. But, if the moderator said that Trump’s covid lockdowns destroyed small businesses and facilitated the largest upward wealth transfer in modern American history, the source said, seventy per cent would disagree.

At the outset of his campaign, DeSantis had a strong base of support among more moderate, college-educated voters. But this base alone is not big enough to win the Republican primaries. “Early on in the race, DeSantis was gonna have to make a decision,” a leading G.O.P. consultant working with a rival candidate told me. One path, he said, would have been to run as a moderate, pull all the anti-Trump people into his camp, and then go to work on the conservatives by arguing that he was younger than Trump, more competent at governing, and likelier to win. The other path was to try to run from the right, even if that cost him the support of his natural base, on the theory that it would be impossible to beat Trump without denting his conservative support and that eventually the moderates would come home because, as the consultant put it, “Where the fuck else are they gonna go?” The DeSantis campaign, he posited, “started with that second strategy. And then the polling tanked and they got scared.”

In truth, a conservative run was a more natural fit for DeSantis. As DeSantis built his national brand, he had leaned heavily into a hard form of culture war: attacking Disney and pushing laws that curtailed the teaching of gender- and race-related topics. It would have been tricky for even the most adept politician to pivot from this to a moderate pitch of good governance and policy. The DeSantis campaign also seemed to lack Trump’s appeal to what the source familiar with the campaign called the “deep base instincts” of the Republican Party.

Perhaps to compensate for this and to channel the right-wing id, the campaign associated itself with some envelope-pushing young activists and journalists. This backfired. One of them, Pedro Gonzalez, was revealed in June to have sent countless antisemitic messages through Telegram Messenger. (An example: “Not every Jew is problematic, but the sad fact is that most are.”) In July, a young DeSantis speechwriter, Nate Hochman, was fired after circulating a pro-DeSantis video that included a symbol, the Sonnenrad, that is common in Nazi imagery. The rival consultant told me, “I think that was a pretty good peek under the lid about what they’re obsessed with in Tallahassee. And it ain’t improving homeownership rates.”

But, from the start of this year, DeSantis has struggled to identify issues that might appeal to very conservative voters. In February, DeSantis criticized the U.S.’s support of the Ukraine war, but he was forced to reverse his position after some prominent donors threw a fit. In April, as much of the political world was coming to terms with Democrats’ electoral advantage after the Supreme Court’s reversal of Roe v. Wade, DeSantis signed a bill outlawing abortion after six weeks. Even on his signature “anti-woke” platform, he sometimes seemed to be searching for an original message. In April, NBC News reported that DeSantis was carrying around “Woke, Inc.,” the book written by his Republican Presidential primary rival Vivek Ramaswamy, an outsider and former longshot who last week edged ahead of DeSantis in one national poll. DeSantis can sound quite similar to Ramaswamy on the campaign trail: both candidates have called for bans on TikTok and for a “declaration of economic independence” from China, and to “shut down the F.B.I.” (Ramaswamy) or to fire its director (DeSantis).

In February, Ramaswamy had called for the deployment of the U.S. military against Mexican drug cartels (“we gotta go Soleimani on them”), and this month DeSantis said he would use military force and drone strikes against the cartels. Without the same dominant position in conservative media he’d had this winter, DeSantis’s ideas could sound a little generic.

For several years now, it’s been common to hear Republican consultants and pollsters say that Trump dominates among the Party’s conservative base because he is seen as a “fighter.” More than anyone else in the G.O.P. primary, DeSantis has a reputation for political aggression and a track record of conservative efficacy, but that doesn’t seem to have helped him.

Perhaps this characterization of Trump is misleading. Is he really a fighter? He is a yeller, certainly, an expresser, a maker of big threats. He also wanders away from the fights he has started. To think that what Republican voters really want in a Presidential candidate is someone they can trust to complete the border wall may be a misunderstanding of the Party’s base. Trump has managed to always make politics gargantuan: it wasn’t about immigration but a civilizational struggle; it wasn’t about an election but democracy itself. “You have millions of Americans who are literally willing to die for Trump right now,” the source familiar with the DeSantis campaign told me, “and being, like, ‘He didn’t fire Fauci’ is not going to change their minds.”

On August 4th, a verdict of a sort was delivered on DeSantis’s effort to pry the conservative base from Trump. The hotel magnate Robert Bigelow, the largest individual donor to the DeSantis super pac, Never Back Down, to which he’d given twenty million dollars, told Reuters that he would not give any more money to the campaign unless it adopts a more moderate approach, saying that DeSantis “does need to shift to get moderates.” When I spoke with Sarah Longwell a few days later, she told me that, in her last two focus groups of two-time Trump voters, not a single participant had said that they wanted DeSantis to win the nomination; some had said that they preferred Tim Scott or Ramaswamy. When a moderator mentioned DeSantis, Longwell tweeted, one participant had said, dismissively, that he “might be Deep State.”

DeSantis is running haggard on the trail. In recent weeks, he’s often spent his Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays in Iowa, on whose caucuses his fortunes increasingly seem to rest. He wears cowboy boots with slightly raised heels, and his wife, Jill Casey DeSantis, wears cowboy boots, too. The towns are small, the venues impeccably styled, the crowds medium-sized, late-middle-aged, and respectful. “We’re banging out those counties,” DeSantis said to a small clutch of reporters in National, with a forced joviality.

Whether you compare this scene with Trump’s rolling, snarling jam-band tour, now in its sixth year, or with DeSantis’s original ambitions to stage a national campaign, leaning heavily on the airwaves, the Florida governor’s campaign right now looks small. (At the Iowa State Fair this past weekend, the Trump team hired a private plane to “strategically” fly overhead while DeSantis was flipping burgers, according to Semafor.) The qualities that recommended DeSantis six months ago are intact; Trump is in a strong poll position but a perilous legal one. When I followed DeSantis on the Iowa trail last week, at least, the challenge seemed to be the fundamental political matter of what, exactly, he was trying to say.

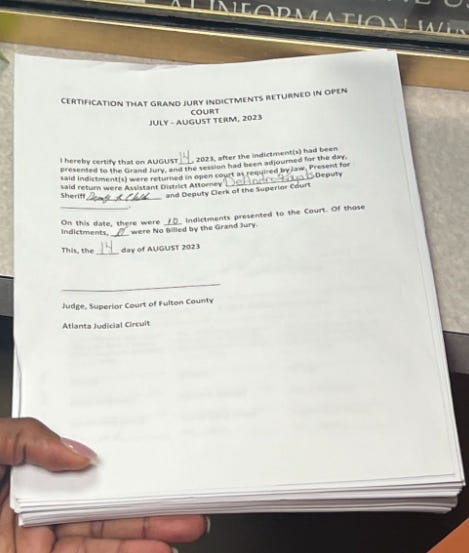

In a brewery on the outskirts of Decorah, DeSantis didn’t tell many stories, about others or himself, or give a capsule version of his biography; perhaps he assumed his audience already knew it. Instead, he sounded much like he does in the format in which he is most adept, the rapid-fire TV interview, ticking through a series of talking points that are familiar to those who follow conservative media closely but can be opaque to others; a line denouncing the excesses of E.S.G. was met with silence. He did not mention his conflict with Disney; the riff on “parental rights in education” was reserved for his wife, who took the mike after him. Was he abandoning the culture-war hard line? It was difficult to tell. I had the impression that he was hedging. During the Q. & A. session, he was asked what he thought about the latest indictment of Trump, this time for his role in the January 6th insurrection. DeSantis replied, “It’s politically motivated—absolutely. . . . They’ve been trying to get him since he became President.” He was more or less making his opponent’s points for him.

If the DeSantis campaign is changing, it isn’t yet obvious how. The source familiar with the campaign told me, “If you’re seeking to understand why this entire operation has been such a disaster, the problem has more to do with the fact that there isn’t any unifying theory of the case and certainly no unifying, coherent message—it’s a schizophrenic campaign with a schizophrenic message.” DeSantis, the source went on, had put himself in the impossible position of trying to be “more moderate than Trump and more conservative than him simultaneously.”

In recent weeks, the campaign had taken note of an anti-Trump message that seemed likely to have some traction with Republican voters: a sixty-second spot, “John,” cut by a pac. In it, a middle-aged man, seated on the steps of a suburban home and speaking calmly to the camera, says that he loves Donald Trump and saw him as a “breath of fresh air,” but that this got him disinvited from his sister’s for Thanksgiving. “The drama . . . he’s got so many distractions, the constant fighting, there’s something every day,” John says. “And I’m not sure he can focus on moving the country forward.” The country is heading in the wrong direction, he adds, “and we definitely need somebody that can freakin’ win. I think you probably lose that bet if you voted for Trump.”

But if this was the sort of message that DeSantis’s supporters hoped might dent Trump’s standing, there was an obvious problem: it did not so much as mention DeSantis. The first debate is on August 23rd, and the best message that the DeSantis campaign has found is not about the Florida governor himself. Like so much else about his candidacy, it exists in wary relation to Trump.

=========END————

Thank you, as always, for reading. If you have anything like a spark file, or master thought list (spark file sounds so much cooler), let me know how you use it in the comments below.

If you enjoyed this post, please share it.

______________

If a friend sent this to you, you could subscribe here 👇. All content is free, and paid subscriptions are voluntary.

——————————————————————————————————

-prada- Adi Mulia Pradana is a Helper. Former adviser (President Indonesia) Jokowi for mapping 2-times election. I used to get paid to catch all these blunders—now I do it for free. Trying to work out what's going on, what happens next. Arch enemies of the tobacco industry, (still) survive after getting doxed.

Now figure out, or, prevent catastrophic situations in the Indonesian administration from outside the government. After his mom was nearly killed by a syndicate, now I do it (catch all these blunders, especially blunders by an asshole syndicates) for free. Writer actually facing 12 years attack-simultaneously (physically terror, cyberattack terror) by his (ex) friend in IR UGM / HI UGM (all of them actually indebted to me, at least get a very cheap book). 2 times, my mom nearly got assassinated by my friend with “komplotan” / weird syndicate. Once assassin, forever is assassin, that I was facing in years. I push myself to be (keep) dovish, pacifist, and you can read my pacifist tone in every note I write. A framing that myself propagated for years.

(Very rare compliment and initiative pledge, and hopefully more readers more pledges to me. Thank you. Yes, even a lot of people associated me PRAVDA, not part of MIUCCIA PRADA. I’m literally asshole on debate, since in college). My note-live blog about Russia - Ukraine already click-read 4 millions.

=======

Thanks for reading Prada’s Newsletter. I was lured, inspired by someone writer, his post in LinkedIn months ago, “Currently after a routine daily writing newsletter in the last 10 years, my subscriber reaches 100,000. Maybe one of my subscribers is your boss.” After I get followed / subscribed by (literally) prominent AI and prominent Chief Product and Technology of mammoth global media (both: Sir, thank you so much), I try crafting more / better writing.

To get the ones who really appreciate your writing, and now prominent people appreciate my writing, priceless feeling. Prada ungated/no paywall every notes-but thank you for anyone open initiative pledge to me.

(Promoting to more engage in Substack) Seamless to listen to your favorite podcasts on Substack. You can buy a better headset to listen to a podcast here (GST DE352306207).

Listeners on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Overcast, or Pocket Casts simultaneously. podcasting can transform more of a conversation. Invite listeners to weigh in on episodes directly with you and with each other through discussion threads. At Substack, the process is to build with writers. Podcasts are an amazing feature of the Substack. I wish it had a feature to read the words we have written down without us having to do the speaking. Thanks for reading Prada’s Newsletter.

Wants comfy jogging pants / jogginghose amid scorching summer or (one day) harsh winter like black jogginghose or khaki/beige jogginghose like this? click

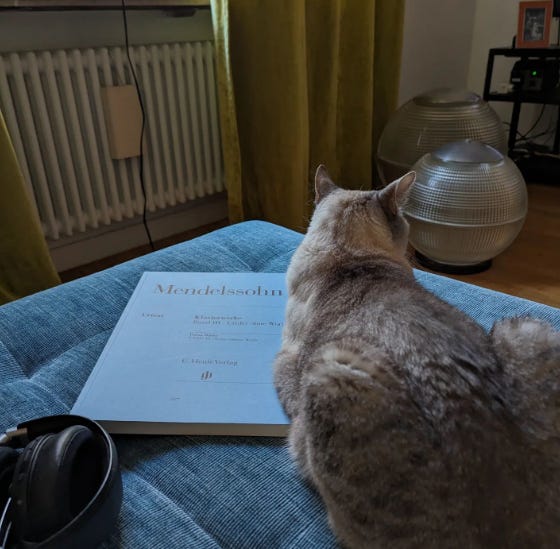

Headset and Mic can buy in here, but not including this cat, laptop, and couch / sofa.