Long time ago, Avril Ramona Lavigne insist to concert in Indonesia just 2 weeks after bomb in Australian Embassy (near KPK/Indonesia Anti-Corruption court trial). After bomb, and maybe already planned long time ago, Australia moved embassy to elite district Patra Kuningan Jakarta (just around 70 meters from the home of late BJ Habibie, former President of Indonesia), maybe the biggest ever Australian Embassy in the world. 2000-2008 Maybe “Peak Performance” Jamaah Islamiyah, branch / cell organization of Al-Qaeda in Southeast Asia. The biggest terror in Indonesia, until today, still Bali Bomb I (October 12nd, 2002).

Currently, nearly 30 defense chiefs and top officials (amid Shangri-La Dialogue 2023 in Singapore) have agreed that a crisis akin to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine must not happen in the Indo-Pacific region, as fears of a U.S.-China conflict grow. In the wake (concern) high tension between China - Taiwan and of course Russia - Ukraine, trackback again how Indonesia spy and Australia spy collaborate after Bali Bomb I. Australia's spies played a crucial part in catching the Bali bombers — but that story has remained mostly a secret.

For two long and intensely frustrating weeks after bombs tore through Bali's nightclub strip, investigators had no idea who was responsible for killing 202 people, including 88 Australians.

What happened next has remained a secret for two decades — but it involved the shard of an exploded Nokia phone, Australian spies and their secret supercomputer.

Three bombs had been detonated shortly after 11:08pm on Saturday, October 12, 2002. The first exploded at Paddy's Bar in Kuta, followed by a second massive blast at the Sari Club across the road.

The detonation of a smaller bomb outside the US consulate in Denpasar betrayed an anti-West motive.

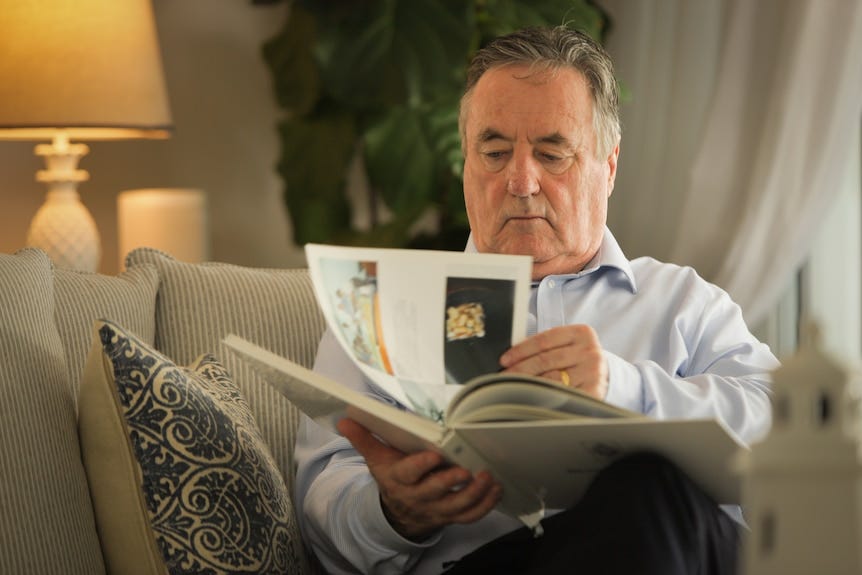

"The crime scene was what you'd expect from a bomb blast," remembers Mick Keelty, who was Australian Federal Police commissioner at the time of the Bali bombings.

"There were bits and pieces of human flesh blasted into walls. Most of the buildings had lost their roofs. There was an engine of a motor vehicle on the second floor of a building that was three blocks away from the blast."

"A bomb attack of that scale, it shocked every one of us," then-head of the Indonesian National Police (POLRI) General Da'i Bachtiar said.

"Even [Indonesian] president Megawati [Sukarnoputri] came to Bali to witness the extent of the damage firsthand."

On the Monday after the attack, the president held a cabinet meeting, where almost every minister criticised the Indonesian National Police for failing to prevent the bombing.

The Indonesian general fronted ministers and prepared himself to be sacked.

"Megawati gave me my chance to speak," Bachtiar told the ABC.

"I said, 'Police have two main tasks: to prevent a crime from happening, and secondly to investigate a criminal case until we find the perpetrators. As the chief of POLRI, I failed my first task, but there is a second one waiting for me.'"

The pressure on Bachtiar was immense. He vowed to resign if he did not bring the bombers to justice.

General Bachtiar phones a friend

The bombsite was still smouldering when then-commissioner Mick Keelty was woken by calls from Indonesia.

"[Bachtiar] asked me how soon I could get some people on the ground," said Keelty, who had already established a trusted relationship with the Indonesian general years before the Bali attack.

By sheer coincidence, AFP specialists were already en route to Jakarta to run a training course on the night of the Bali bombings, after Bachtiar had confided to Keelty over a round of golf in Perth, months earlier, that Indonesia lacked expertise in forensic investigation.

The specialists were quickly diverted to Denpasar, joining other AFP officers who were in Bali already.

Operation Alliance began, led on the Australian side by assistant commissioner Graham Ashton, and on the Indonesian side by Made Mangku Pastika, who Keelty also knew well, having trained with him in the 1980s.

'The answer will come from the skies'

Even with some of the world's best forensic investigators onsite, the Bali bombing was proving immensely difficult.

The Sari Club blast was so big it had left a deep crater that had filled with water. And there was also a question of culture: In keeping with the Muslim faith, Indonesian authorities wanted to remove the bodies for burial within 24 hours.

After a fortnight of frustration, the only solid leads that Pastika and Ashton had to offer were a white mini-van that was used to carry the Sari Club bomb — its chassis and engine numbers filed off — and the probable ingredients of the explosives used.

Pressure was mounting on investigators.

And after meeting with Indonesian spy chiefs in Jakarta alongside ASIS director-general Allan Taylor and ASIO boss Dennis Richardson, Keelty believed Pastika's team was being poorly advised by Indonesian intelligence.

"Their briefings did not match what we were getting from the crime scene, their briefings were way off," Keelty said.

It was clear this investigation required some special detective powers.

"Pastika knew this already — he'd looked in the skies and said, 'The answer will come from the skies,'" Keelty said.

"I knew that he was a practising Hindu ... he prayed every day. And I said, 'You mean from God?' and he said, 'No, no, no: from satellites.'"

Clues hidden in a seismogram and a Nokia

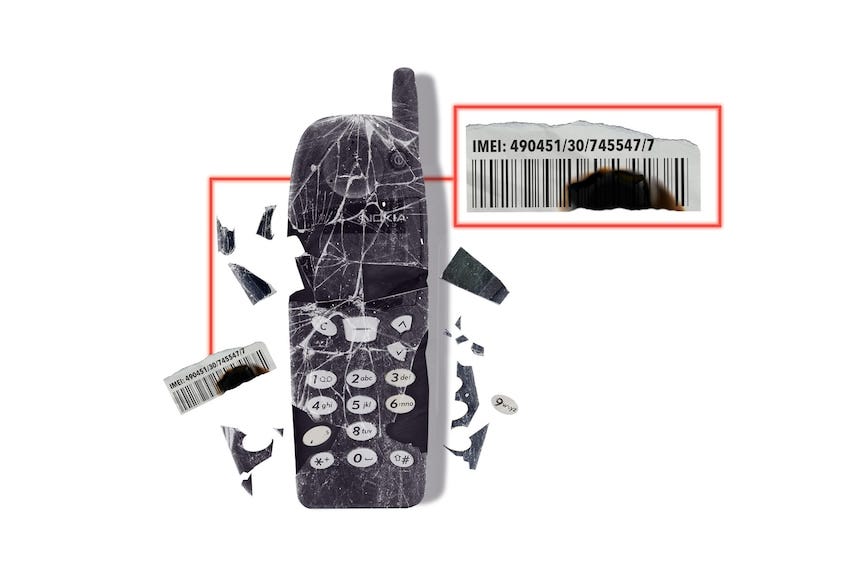

Luck changed for investigators when forensic crime scene examiner Sarah Benson found the tiny fragment of a Nokia 5110 mobile phone outside the US consulate. This was the smallest of the three bomb blast sites — and the most forensically clean.

Luckier still, that fragment contained the Nokia's 15-digit serial number, or IMEI number.

"The IMEI number is unique to each mobile phone," Keelty said. "You can change SIM cards on phones but the IMEI number remains the same."

Nokia 5110 phones had been used by terrorists elsewhere in the world because they were known to produce sufficient electric charge when they rang or received a text message to set off explosions.

Knowing who owned the Nokia phone, or who rang it to detonate the bomb outside the US consulate, were potential leads.

But these leads required the phone data held by Indonesia's government-owned mobile provider Telkomsel.

And another important clue had emerged: The Sari Club explosion was so enormous it had been picked up by seismic sensors, pinpointing the exact moment of its detonation: 11:08:31pm Bali time.

The AFP believed the Sari Club explosion, like the one outside the US consulate, had been detonated remotely.

"The organisers made sure that these suicide bombers didn't back out at the last minute. So the bombs were being detonated by mobile phones," Keelty said.

"We knew that if we overlaid the data from the seismic blast with the data from telephone records, that we would be able to pretty much precisely identify what the number was that was dialled that detonated the other bombs."

With the full understanding of Pastika's team, AFP and Telstra technicians went to the Jakarta headquarters of Telkomsel to request access to the company's mobile phone data.

"When we went with the Indonesian National Police and our Telstra colleagues to Telkomsel, we basically were explaining to the Indonesian National Police at the same time how we were using analysis of analogue phones and cellular phones in Australia, and the success we were having in criminal investigations."

Access was granted.

"The crime scene was one thing but in terms of the telephone network and the data that Telkomsel had, that was pretty much untouched, it was pristine. This was what I would call a goldmine," Keelty said.

But it was a goldmine too rich for the Indonesian or Australian police to mine.

Australia's most secretive agency joins the hunt

Australian law-enforcement agencies had never dealt with the scale of information that came from the Telkomsel data.

Police needed Defence or, more specifically, the super-secretive Defence Signals Directorate (DSD) based in Canberra.

DSD held one of the only supercomputers in Australia capable of handling the data, and the then-heads of DSD and Defence agreed that this immense computing power should be offered — discreetly — to scour the phone data.

Keelty and Australia's ambassador to Indonesia were also on board — after all, then-prime minister John Howard had ordered the Bali investigation be a diplomatic and intelligence priority.

Shockwaves of Bali bombings, 20 years on

But the rule of law in Indonesia was paramount: There was no point in having an investigative tool if it could not result in arrests that would satisfy the local justice system.

"We didn't want to know how [DSD] were doing it — or any of their methodologies — because if we did, we would have to give it in an open court," Keelty said.

"So we had to have this, if you like, Chinese whisper going on between Defence Signals Directorate and our own people on the ground and just point our people in a direction as to where to go."

DSD's big, 'daggy' supercomputer

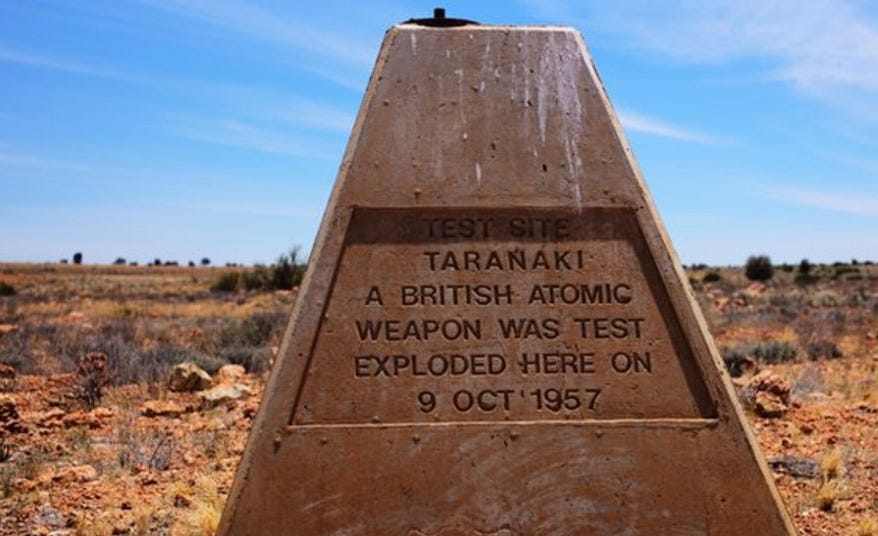

Long before the Bali bombings, DSD was sweeping up huge amounts of data through its satellite intercept station outside Geraldton as part of its role in the global surveillance network Echelon, operated by the Five Eyes intelligence partners: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States.

And to make sense of mass data, you need computers with grunt.

"Before big data was even mentioned, signals intelligence agencies like ASD were very much in the big data game and they had clever people who could analyse that and find the needle in the haystacks," former ASD director-general Mike Burgess, now ASIO boss, said.

"And that's the secret of the signals intelligence organisation. It's not just understanding how things are communicating, getting to the pinpoint of the communications by breaking codes. You know, there's a lot of data you need to target the right individuals."

DSD was the first Australian organisation to obtain a Cray supercomputer in the 1980s — bought by Jim Noble, the father of current ASD director-general Rachel Noble.

"It's a hilariously daggy-looking thing, I've got to say," Rachel Noble said of the agency's first Cray computer.

"Your iPhone has thousands of times more processing capacity than that supercomputer, but when we bought it in 1986, it was the first in Australia and the first in the southern hemisphere, and it was an absolute game changer for the organisation."

Neither Noble nor Burgess were willing to detail DSD's involvement in the Bali investigation.

Nokia's last call unravels the crime

DSD's supercomputers at HMAS Harman, on the outskirts of Canberra, got to work analysing Telkomsel mobile phone data generated by tens of millions of people on its national network, making hundreds of millions of calls and text messages.

"This was the biggest lead in the investigation, and the most important lead in the investigation, because it was a pristine piece of evidence that could be looked at and could give immediate results, which is what it did," Keelty said.

"Network analysis was not easy. It's extremely complicated," Bachtiar noted. "There were thousands of phone numbers involved, but we were able to identify and find the pattern."

The Nokia 5110 used to trigger the US consulate blast had received one final call from a number DSD identified in the Telkomsel data.

This helped Indonesian National Police trace the owner of that number, hunting him down through a Bali retailer.

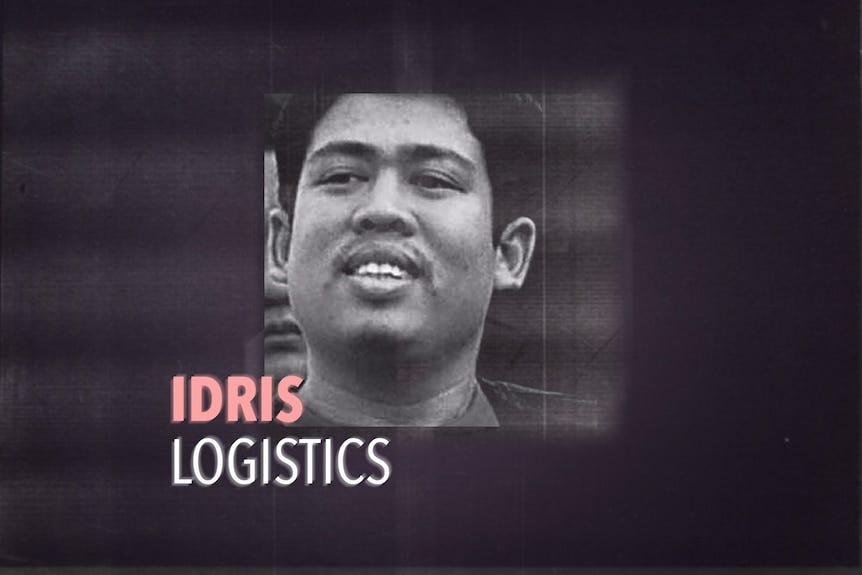

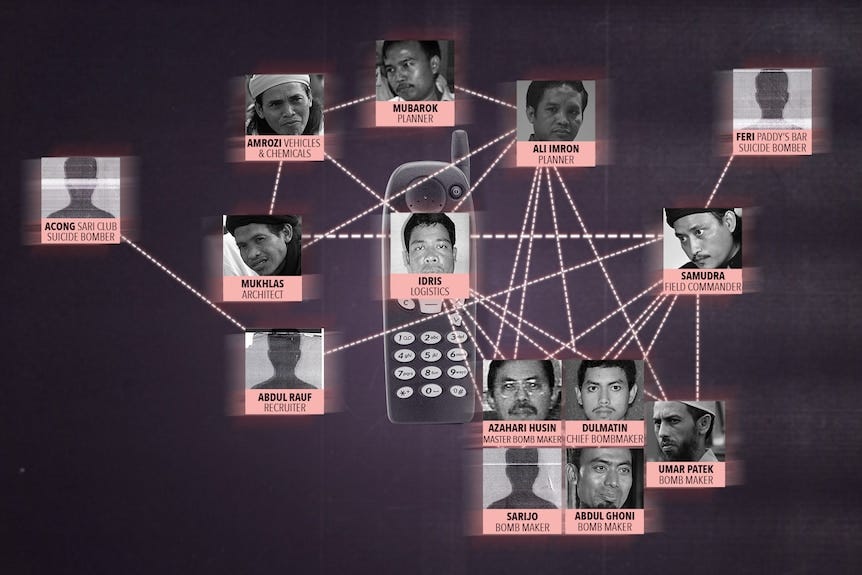

His name was Idris.

He was the logistics man who had not only called the Nokia 5110 but also bought SIM cards and arranged transport and accommodation for the Bali bombers.

"Idris was the hub, and the spokes went out from the hub to the rest of the wheel, and the rest of the wheel is what drove the bombings," Keelty explained.

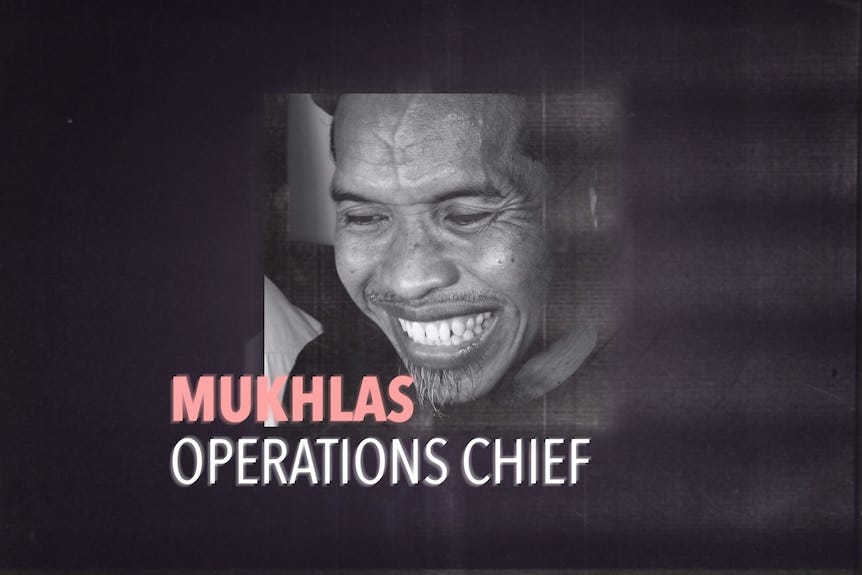

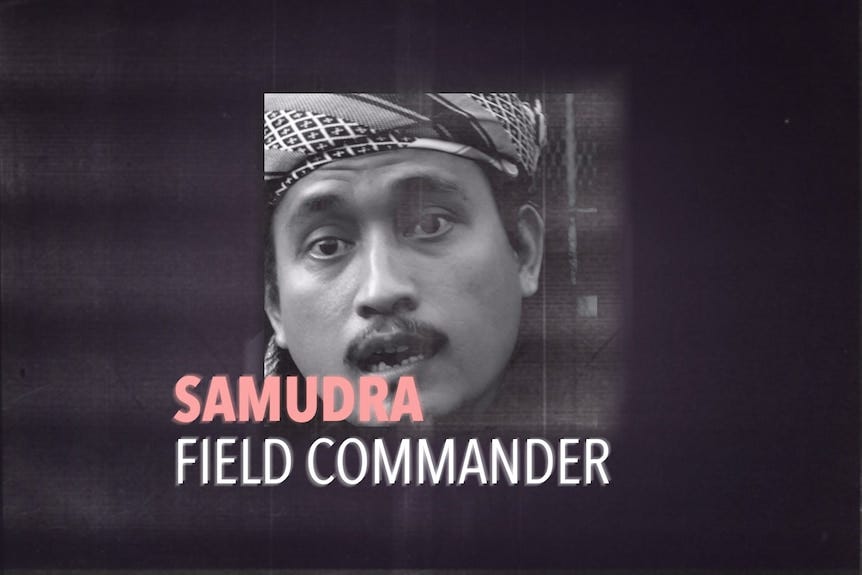

DSD's analysis of Idris's calls and texts, combined with phone data extracted from the precise moment of the Sari Club explosion, established the bomber's command team: Mukhlas, who was the operations chief for terror group Jemaah Islamiyah, and his field commander Imam Samudra.

Establishing the web of terrorists required an iterative process, with information passing back and forth between Canberra and Denpasar.

DSD would scour the phone numbers for good leads, allowing Indonesian and Australian police on the ground to follow them up. In return, DSD would receive tip-offs from investigators in Bali on numbers to check, and the process was repeated time and again.

"That reverse network analysis was critical to unravelling the network of terrorists," ANU's international security and intelligence studies professor John Blaxland said.

"And that was a real breakthrough, an extraordinary breakthrough, that saw trusted collaboration between Australia and Indonesia, the likes of which we've actually never seen before."

Investigators close in on terror cell

Meanwhile, the lead Indonesian investigator Pastika had been frustrated by the absence of forensic clues coming from the white mini-van that had exploded outside the Sari Club. He ordered his officers to take another look at the wrecked engine.

His gut instinct was spot on — and it further confirmed the cyber sleuthing being conducted 4,500 kilometres away in Canberra.

"We found another clue from a small Transport Ministry registration plate," General Da'i Bachtiar told the ABC.

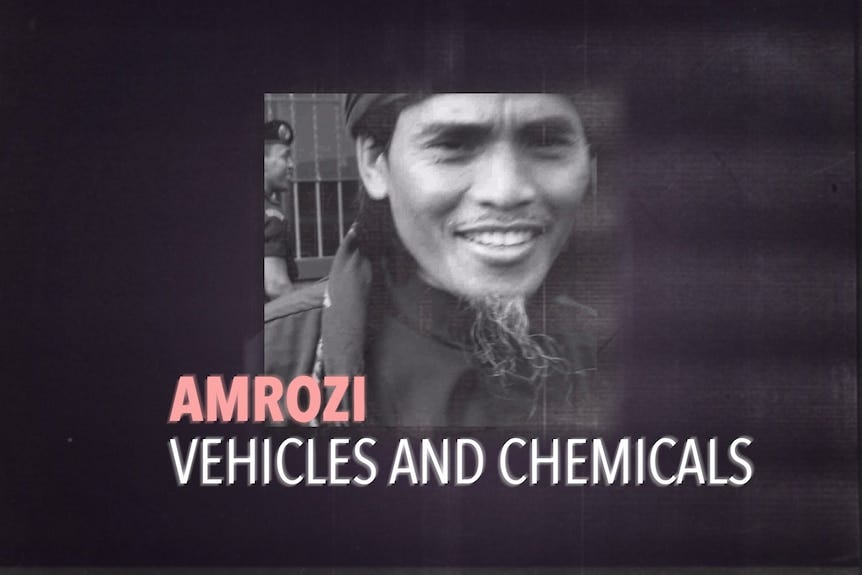

"We traced that plate and we found that the car had gone through six owners, one after another, and ended up with Amrozi who lived in the small village of Tenggulun in East Java."

Amrozi was the brother of operations chief Mukhlas.

DSD cross-checked the exceptional police work by POLRI and identified another one of the bomb plot lieutenants, Ali Imron, who was also a brother of Mukhlas.

With DSD's help, investigators next identified the bombmakers, who included Jemaah Islamiyah's explosives expert Azahari Husin, as well as recruiter Rauf Abdul and the suicide bombers who targeted Paddy's Bar and the Sari Club.

Triangulation of DSD's data allowed the Indonesian and Australian police to geolocate the suspects using equipment AFP took to Bali.

The 'smiling bomber' Amrozi coughs up

The first arrest was Amrozi, dubbed the "smiling bomber", who was quick to cough up his co-conspirators.

"Some of those people were arrested in towns where there are millions of people," Keelty said.

"But getting those first arrests was so crucial because some of those people cooperated. And we could test their cooperation because we actually had the data."

"This was AFP's role in the Bali bombing case," Bachtiar said.

"From one suspect, Amrozi, we could dismantle the whole network and we just found out that there was a group called Jemaah Islamiyah."

Bombing mastermind Mukhlas attempted to evade detection by regularly swapping SIM cards, not knowing that DSD was tracking him through his phone's unique IMEI number, leading to his arrest by POLRI in central Java.

Samudra was also swapping SIM cards and turning his phone off and on when he needed to text or call, which only aided Indonesian and Australian data analysts in identifying suspicious activity.

"Yes, it was interesting to learn what the terrorist considers 'hiding' their number," Bachtiar said.

"By turning off the phone and taking the SIM card out, it gave us clues to find them."

Armed with geolocation data accurate to a radius of 500 metres and a facial description given by Amrozi, Samudra was eventually arrested at the Merak ferry terminal.

"We found Imam Samudra sitting inside a bus waiting for the crossing, in the back row, after tens and tens of people had been arrested before him, within the 500-metre radius," the Indonesian general said with a wry chuckle.

"Thank God the technology could reveal him."

General Da'i Bachtiar, returning successful to the government ministers he had feared would sack him, advised President Megawati to invest in the same Australian technologies that had helped pin down the Bali bombers.

"I thank Mick so much for that support and even more," Bachtiar said.

"We want to show the world that joint Indonesian-Australian police cooperation made this all work."

Mick Keelty said without DSD's wizardry, the investigation might have foundered.

"What we got from DSD and the other Australian government agencies … it was just brilliant," Keelty said.

"It had to be handled with care because … behind DSD, sits the Five Eyes community and the capability for war."

Depending on who is telling the story, the Bali Bombing in Kuta, Indonesia on 12 October 2002, which killed 202 people and injured over 200 more, involved a cast of thousands.

There were the two brothers, Muklas and Amrozi, who were executed in 2008 for masterminding the plot. There was "field commander" Imam Samudra. There was Umar Patek, who said that all he had done was “mix chemicals” and, even then, only for church bombings in other parts of Indonesia. There was Abu Bakar Bashir, the spiritual leader of the Islamist extremist group Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) that took responsibility for the bombings, who had allegedly given his blessing to the bombers.

There was another “mastermind”, Hambali, now incarcerated in Guantanamo Bay, and “military commander” Zulkarnaen. There were explosives experts Dulmatin (“the Genius”) and Idris. There were Malaysian nationals Nurdin M. Top ("Money Man") and Dr Azahari ("Demolition Man").

And there was Osama Bin Laden, the frontman of the terrorist group Al Qaeda, who apparently presided over the proceedings and sent USD 30,000 to the bombers to pay for the carnage (who exactly the money went to is disputed to this day.)

Many of these men are now dead. Some died in hails of gunfire in police raids, while others faced a firing squad at the request of the state. Some are old and infirm, their memories and their power faded as the years have passed. Some are in maximum security penitentiaries from which they will likely never be released and where, if you believe their lawyers, they have been waterboarded and confined in false coffins. Some lie in unmarked graves, their bodies committed to the ground or the sea to rest eternal.

But there is another man about whom less is known. His role remains, even now, in the shadows, even though, he claims, he was the Sun around which the Bali bomb plot orbited.

“If terrorists are arrogant, then I’m the most arrogant of all,” he says. “I did everything. I was instrumental in the Bali Bombing. I made the plans, I sourced the locations, I picked the houses, and I set up the detonators.”

“The things I touched changed people’s lives forever. And many of them are no longer with us.”

Ali Imron is the younger brother of Muklas and Amrozi. He sends his story from his cell in a wing of Jakarta’s Police Headquarters. Imron has been in prison for almost 20 years for his role in the bombings and, barring a presidential pardon, he will likely never be released.

“I want my voice to be heard, but I know it’s difficult,” he says.

He shares the wing in the police headquarters with another convicted member of the bomb plot named Mubarok. Imron, now 51, spends his time playing table tennis with other inmates, reading his extensive book collection or running on his treadmill. Mubarok, an explosives and electronics expert, fixes broken mobile phones and computers belonging to the guards.

“In this cage, everything is limited by bureaucracy," says Imron. "It’s heavy inside. I think, ‘Why do others get to be outside while I’m in here?’ ‘How come my friends get to be outside?’ It’s because the government and the police have said so. And people believe them.”

A Message to America

The plans for the Bali Bombing were as follows: one bomb in a suicide vest to be worn by a bomber who would enter a packed nightclub; one larger bomb in a mini-van to be detonated by another suicide bomber; and another bomb targetting the US Consulate.

“We decided that a suicide bomber would go into Paddy’s Pub and detonate his vest when he saw our van pull up in front of the Sari Club across the street. The bomb at Paddy’s was just to fish the Westerners out, to get them on the road so we could blow up the van," Imron explains.

The codename for the attack: Operation Beach.

Imron first came to know of tentative plans to attack Bali in 2001 when he met Imam Samudra, Amrozi and Muklas in Solo in Central Java. The men were all members of JI, the group that claimed responsibility for the bombing, and which had been active in fighting in the civil conflict between Christian and Muslim communities in Poso in Sulawesi. While the men had toyed with the idea of setting off a large bomb in Poso or in Ambon on the island of Maluku, they had decided to turn their attention to Bali instead for maximum impact.

“It was because of America fighting in Afghanistan. We discussed that if we wanted to retaliate, we should blow up an American naval vessel at a port in Indonesia. Those on board would not have been without sin because they were American soldiers. We called them ‘fish’,” says Imron. “But then Muklas said that America’s war on Afghanistan had killed and injured civilians, so attacks against Western civilians were also permitted. Like Westerners in bars in Bali.”

In the minds of the bombers, the victims symbolically represented the atrocities committed by the United States against predominantly Muslim countries, although that rationale was flawed from its conception, as Bali is far more popular with Australian travellers due to geographic proximity. As it was, the majority of the victims, 88 to be exact, were from Australia, compared to seven from the United States. It would appear that the bombers were either unaware of the disproportionately higher numbers of Australians in Bali, or misinformed about the likelihood of any impact on US politics or foreign policy as a result of the attack.

By August 2002, Amrozi had rented a house with Samudra and Muklas, the latter of whom had relocated to Indonesia from Malaysia where he was actively wanted by the police for other suspected terrorism offenses. The house became the headquarters of Operation Beach, with Bali now fixed as the location, despite another vague idea to blow up part of Singapore using imported explosives from the Philippines (a plan that had previously been thwarted on a number of occasions by the local authorities). “Muklas had been convinced by Imam Samudra that Bali was a good idea and so three bombs there became our plan,” says Imron. He adds that he was hesitant about the idea from the beginning and asked two questions of Amrozi, Muklas and Samudra.

“Is this really jihad?”

“Yes,” came the reply. “Osama Bin Laden says so.”

Bin Laden was like the spiritual godfather of JI, and Al Qaeda’s organisational structure served as the blueprint for JI's military wing. The group adopted Al Qaeda’s military style, organising members in “battalions” and integrating farsi and pashto terminology for ranks like “colonel” and “major”. Both Muklas and Imron had trained in military combat and demolition techniques in Afghanistan under Al Qaeda, as had many other JI operatives, some of whom had met Osama Bin Laden in person. "He looked shorter than he did on TV," one current JI member tells Hukum. "And he was quite scrawny and quiet."

Notwithstanding the apparent blessing from Bin Laden, Imron’s second question focused closer to home. He wanted to know if JI as an organisation unanimously supported the plan.

“If we tell absolutely everyone, maybe it won’t be unanimous," one of the men replied. "So that’s not our business."

Yet despite its obvious flaws, the bomb plot bore all the hallmarks of the definition of terrorism in its most basic form: a political act of violence designed to create maximum physical and psychological damage. To the bombers, the optics of the attack were as important as the plan itself. Everyone would be watching, including high ranking members of JI who still claim they had little clue what was to come—having not been directly consulted about the plot. This rather coy attitude adopted by Muklas, Amrozi and Samudra meant that many JI operatives saw the carnage unfold in real time along with everyone else. “I couldn’t believe it when I saw it on TV,” one tells Hukum. “I thought ‘Operation Beach’ meant the promenade in Ambon which was popular with Westerners. I had no idea it meant Bali.”

In the beginning, Imron’s role was modest: he was tasked with accommodation arrangements so as not to be directly involved in the more nefarious aspects of the plan. Perhaps because he was younger than Muklas and Amrozi, and less experienced than Samudra, he was only judged suitable for light logistics work—a decision that rankled. Being put in charge of accommodation seemed to Imron a thankless role, and one well below his talents. As the youngest of the three brothers—forever in their shadows, even now—he made up his mind that he would show them what he was capable of.

Imron, Amrozi and Muklas grew up in Lamongan in East Java with ten other siblings. Their grandfather opened the first Islamic boarding school in the area, and their father believed in the Sharia state, vocally rejecting Indonesian laws and customs. With this start in life, the three brothers were typical of many other terrorists who joined and still join the ranks of JI. They were generational terrorists, imbued with radical ideology from the cradle to the grave.

Imron says that Muklas was always the star of the family: ambitious, charismatic and intelligent, while Amrozi was dim-witted and frequently in trouble at school. Imron skirted somewhere in between, having trained in Afghanistan from 1991 until 1996 following Muklas who had been there from 1985 to 1990.

Amrozi had never trained under Al Qaeda, choosing instead to follow a life of petty crime, drinking and chasing women, something his more devout brothers, particularly Muklas, strongly disapproved of. Muklas and Amrozi reunited later in life before hatching the Bali Bomb plot, with the older brother acting as a firm hand to his wayward younger brother and bringing him into the fold of JI along with other senior group members like Samudra.

Muklas and Samudra had lived together in Malaysia, where a number of JI members, including spiritual leader Bashir, had fled to evade capture in Indonesia and opened Islamic boarding schools that also fronted as JI recruitment centres. It was there that original plans for Operation Beach are thought to have germinated.

Back in Indonesia, on 8 September 2002, Samudra asked Imron to go to Bali with him on a fact finding tour of the island before the bombing. They stayed in a cheap hotel on Jalan Teuku Umar and rented a car to cruise around famous tourist hotspots like Jalan Legian where the majority of the bars and clubs were located. The group also consisted of bomb maker Dulmatin and tensions were high as the three men bickered about the possible logistics of the bombings. “Dulmatin and Samudra were both equally stubborn, and I was worried that they’d end up fighting on the trip,” says Imron, who tried to quell the tension.

In the black of night, the men drove up and down the Balinese streets as the neon lights of the bars and clubs scattered across the car’s windscreen, looking for the best place to strike.

“It was like we were hunting them,” says Imron. “We were looking for a fishing hole. There were so many Westerners. The Sari Club was obviously the busiest club on Jalan Legian, and Indonesians weren’t allowed to go inside. I tried, but they wouldn’t let me in if I didn’t pay. They were so arrogant and rude.”

Imron had never been to Bali before, and he had just come up against one of its most controversial practices that still exists to this day: dual pricing. Many of the bars and clubs on Jalan Legian are free to enter for foreigners, while locals are expected to pay a hefty entrance fee. The “justification” for this, is that foreigners are likely to spend more money inside in the venues than locals, although it is also hard not to see the door policy as anything other than deliberate racial segregation.

While the decisions made to carry out the Bali Bombing did not stem exclusively from the deeply rooted racism and white supremacy that stalks the island, and which Imron experienced firsthand that night, the door policy only made him more determined to execute the plan with maximum carnage inflicted. “We wanted the bombing to go right, so I knew it was important to get a suicide bomber actually inside one of the clubs,” he says. “It was my decision.”

Imron and Samudra stayed in Bali for two days and one night, driving to other parts of the island like Sanur and Nusa Dua to assess whether they could also be potential targets, but were disappointed by the lack of Westerners there compared the main arteries like Jalan Legian. In the end, they settled on two locations along the main street, in addition to an attack on the American Consulate in Renon Denpasar.

Operation Beach Begins

Originally, 11 September was chosen as the day the foreigners in Bali would die—to commemorate and celebrate Al Qaeda's attack on the World Trade Center in New York. But time was tight, and the bombers provisionally moved the date to 11 October, before Operation Beach finally swung into action on 12 October—a Saturday night, when the clubs and bars in Bali were busiest.

It started with planting the bomb at the American Consulate.

“We decided to take a motorbike to Renon, but when we set off, there were police everywhere. That scared us, but it turned out that they were just traffic police. I activated the bomb and put it on the pavement. It was a message to America. I waited in a small square and used a remote on a mobile phone to detonate it,” says Imron.

In ensuing media coverage, it was widely reported that bomb maker Dulmatin set off the device, which Imron denies. Whoever set it off, however, succeeded only in blowing up part of a tree next to the pavement.

From Renon, Imron transferred to a van stuffed with explosives. It had been bought back in Solo and miraculously already had a Balinese number plate which made it blend in with the other vehicles on the island. “It was perfect,” says Imron of the van.

Seven volunteers stepped forward to act as suicide bombers and two were chosen, named Iqbal and Jimmy. Imron and Jimmy dropped Iqbal off and then drove the van along Jalan Legian. It had been packed with small filing cabinets filled with TNT and flash powder made up of potassium nitrate and sulfur which weighed it down significantly. “It was so heavy because of the bomb that it was creaking the whole way,” says Imron.

“The second suicide bomber [Jimmy] was in the van with me and, unfortunately, he couldn’t drive."

The suicide bomber had been given a crash course the day before, just enough for him to keep the van in a straight line, but when Imron gave him the steering wheel, a miscommunication ensued. “I activated the bomb and the suicide bomber started screaming. He thought I was going to detonate it, and that it was going to go off in the van with me inside,” he says.

Imron got out of the van and was picked up on a motorbike by another bomb maker named Idris, before speeding off into the Balinese night. But then he discovered a problem: the bomb in Jimmy's suicide vest had a remote control to set it off and which Imron was meant to trigger. In the melee, he had left it in the van with the bomber.

Imron and Idris started to wonder if they should turn back towards Jalan Legian. But by this time, they suspected, in accordance with the plan, the first suicide bomber, Iqbal, had already walked into Paddy’s Pub and detonated his suicide vest, sending panicked patrons out onto the street in front of the Sari Club.

Imron and Idris started to dither.

“Then I heard a huge explosion.”

In addition to the remote control, the suicide vest worn by Jimmy had been fitted with a manual button in case of mishaps of this kind. Perhaps growing impatient, he had triggered it himself.

The suicide bomb ignited the TNT and flash powder in the van. The ensuing blast left a one metre wide crater in the road.

Imron says that he froze when he heard the explosion. “I couldn’t even smile. I was speechless. I couldn’t believe that we’d done it.”

Idris and Imron drove around Denpasar in a daze, looking for a place to leave the motorbike and hoping someone would steal it. “At 1.30 am, we left it in front of a mosque and went to meet Imam Samundra. But no one took it, instead they reported it to the police.”

Perhaps this miscalculation hints at the worldview of the Bali Bombers. Looking for a place to dump a motorbike in a tourist hub filled with the usual petty crooks and thieves, they gravitated to the most unlikely of places in the hope it would be stolen—a Muslim house of worship.

Perhaps they simply couldn’t conceive of anywhere else to go.

Success And Failure

Imron had mixed feelings about the relative success or failure of the bombings, even then. He says that the Sari Club was chosen as it was the busiest club on the main strip, but it also ended up being the perfect target for another reason: its thatched roof made of latticed palm fronds. Once the bomb exploded, the roof of the club caught fire causing a mass stampede. The roof collapsed, trapping victims inside where many died of smoke inhalation in addition to severe burns.

“When we saw the news reports, and found out we’d killed 202 people, I was amazed. I never thought we’d get that many,” says Imron. “But we were aiming for 600, and I still believe that the real number was higher.”

There is perhaps some basis to support this claim as, in the days that followed the bombing, it is thought that some of the Indonesian casualties returned to their home villages before succumbing to their injuries, meaning that their deaths were not recorded in the official death toll.

And while it may seem baffling that Imron was proud of having managed to kill more than 200 people, maybe achievement is relative. For once, he was a success in front of his brothers, even if only in the macabre and tightly drawn definition of a mass murderer.

Imron was arrested hiding out in East Kalimantan at the end of November 2002. Amrozi had been arrested a few weeks prior. “After his arrest I waited for 20 days in Kalimantan for fate to catch up with me too,” he says. “I ran into the forest, but they still caught me.”

Now, he says, he regrets the bomb and has used his time in prison to make amends and meet with families of the victims.

“One woman once asked me why her husband had to die. The first thing I always do is apologise. People always tell me that it is easy to say sorry, but what else can I do? I work with the police now because I respect the families and the victims. I don’t want to hurt them any more.”

“I could make bombs in here, but I don’t. I could still be active underground. If people still want to be active in jihad, they can go to the Philippines. I’m deradicalised now and I’ve deradicalised others as well. I’m not pretending. I don’t want to be free just for the sake of it, but to help campaign about deradicalisation. To my friends who still have radical thoughts or members of the public who want to join radical groups, I just have this to say: don’t join a terrorist network.”

Amrozi called Imron the night before his execution. He had been handed a death sentence for masterminding the plot and was executed on 9 November 2008. According to Imron, his older brother seemed in good spirits, just as he had been throughout his trial where he had beamed at the assembled media, frequently shouting out “Allah Akbar'' and giving a thumbs up. Once he sang a self-penned song to the cameras about “getting rid of the Zionists”, with his cheerful demeanour earning him the moniker, “The Smiling Bomber”.

In the Australian media, it was reported that Amrozi was “pale and shaking” before he faced the firing squad, which is something Imron disputes. “He said on the phone, ‘Well...it [the execution] seems like it’s happening’,” says Imron. “He was sure they were all going to go to heaven, so he just kept laughing. I’m sad Muklas and Amrozi were beaten down for opposing the state,” he adds. “I miss them.”

Amrozi, Muklas and Samudra were the only members of JI who received a death sentence in relation to the Bali Bombings.

Nurdin M. Top, who apparently supplied money for the plot and was once Indonesia’s “Most Wanted Terrorist”, was killed in a police raid in 2009. Suspected “technical mastermind” Dr. Azahari died of a bullet wound to the chest in another police raid in 2005 and bomb maker Dulmatin died in a similar raid in 2010. Fellow bomb maker Idris was acquitted of his role on a technicallity and sentenced for other terrorism offenses before being released from prison in 2009. Explosives expert Umar Patek was captured in Pakistan in 2011 and extradited to Indonesia where he was sentenced to 20 years in prison for bomb making.

JI's spiritual leader Abu Bakar Bashir (now 82) was released from prison in January 2021 having served 11 years of a 15 year sentence for financing terrorist camps in Indonesia, having never been found guilty of any involvement in the Bali Bombing. Zulkarnaen, the military commander of JI at the time of the bombings, was arrested in December 2020 and is awaiting trial, having been on the run for 19 years. Hambali, who allegedly provided the critical link between JI and Bin Laden, was arrested in Thailand in 2003 and is now thought to be housed in the infamous "Camp 7" of Guantanamo Bay where he awaits trial in a military court.

Imron met Hambali once, before a set of church bombings in 2000, and describes him as “laid back and encouraging about the Christmas church bombing programme.” He adds that, as far as he was aware, Hambali had no involvement in the bomb plot, and follows up with a question. “Has the Pentagon said when the trial will be?”

Bin Laden, who Imron says sent the money to finance the plot directly to Mulkas, was killed in Pakistan and his body buried at sea in 2011.

When his turn came, Imron sobbed in front of the judges at his trial and only escaped a death sentence after expressing remorse and apologising profusely. “I knew what I was doing when I got involved with JI. I knew the risks of the Bali Bombing plot if I didn’t die,” he says. “I was ready to accept my fate.”

“I will never plant another bomb again. Whenever I have the opportunity, I always say that to people. That is all I can do. And look at Bali...are there no more Westerners in bikinis on the beach because of what we did? Of course not. To the next generation, I say, let God guide you.”

He elaborates by describing the Bali Bombing as “an explosion that went off” because he followed the wrong path.

“The plan was flawed. So many people died who’d never done anything wrong. I had said to Muklas, ‘Let’s cancel it. Is this really jihad?’ I always doubted the plan, but it was already in place. Even if I hadn’t gone that night, it would still have happened.”

“But I feel that me being there had a purpose too,” Imron says.

“Who would tell you all of this, if I wasn’t here now?

The story of the Bali investigation is featured in BREAKING the CODE: Cyber Secrets Revealed which airs at 7:30pm on June 4 on the ABC News Channel and at 10:30pm on June 5 on ABC TV. You can also watch it on ABC iview.