Everybody wants peace. That’s not the issue. The issue is how to get to that point. Zelensky thinks he can do it cleanly: beating Russia militarily and getting it to surrender like Imperial Japan in Aug 1945. Now, Japanese PM Kishida Fumio thinks he will beat Xi Jinping, and (if he thinks like this) it's dangerous.

Prime Minister Kishida Fumio will meet Biden in DC, January 13rd (finally happens). The leaders will have much to talk about, including Japan’s plans to bolster its armaments with purchases of Tomahawk missiles from the U.S. Japan earmarked more than $2 billion to buy and deploy U.S. Tomahawk missiles on its naval destroyers, enough for several hundred of the weapons as it seeks to deter China and North Korea. The spending is part of a record defense budget approved by the cabinet Friday, equivalent to $51.4 billion for the fiscal year starting in April. Tokyo last week signaled one of its biggest military buildups since the end of World War II with plans to nearly double military spending over the next five years.

Japan’s shifting security policy, highlighted in a series of key documents revised late last week, has put the spotlight on what will be its top priority in the coming years: reinforcing its far-flung southwestern islands, which would be uniquely exposed in the event of a conflict with China.

More troops, new units, enhanced military capabilities and better medical provisions are just some of the elements laid out by Tokyo in the three documents, with Japan beefing up defenses on and around the Nansei Islands amid concerns that a crisis akin to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could occur in the area.

Japan is not yet buying another “special weapon”: HIMARS. But another ally in QUAD, Australia, does. The Australian Army will soon be acquiring HIMARS missile systems - these have been absolutely crucial in the fight to defend Ukraine. This is great for the national security and defence of Australia. To imagine distance, one fired by HIMARS from Bamaga (Australia) may hit an object in Merauke (Indonesia). If HIMARS fired from Kalumburu (Australia), may hit an object in Kupang (NTT Indonesia).

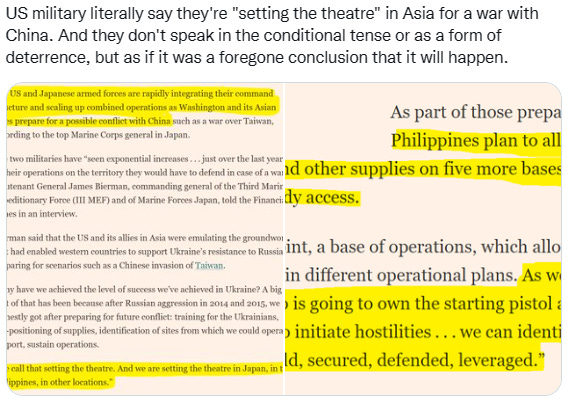

Protesters in Japan demand to stop negotiations with the U.S. to purchase weapons like Tomahawk & F-35s,as it’s widely used as a first-strike weapon, which violates the Constitution. Japan's long range missiles make no sense unless they're to be used for attack, smart citizens oppose this.

Awkward: The late (former PM) Abe Shinzo, via his Defense Minister Taro Kono, scrapped THAAD plan in 2020. But yes, in 2020, no sign Russia - Ukraine will conflict. No sign that China is more hawkish about Taiwan.

Japan’s Defense Ministry said in June 2020 that it has decided to stop unpopular plans to deploy two costly land-based U.S. missile defense systems aimed at bolstering the country’s capability against threats from North Korea.

Defense Minister Taro Kono told reporters that he decided to “stop the deployment process” of the Aegis Ashore systems after it was found that the safety of one of the two planned host communities could not be ensured without a hardware redesign that would be too time consuming and costly.

“Considering the cost and time it would require, I had no choice but to judge that pursuing the plan is not logical,” Kono said.

The Japanese government in 2017 approved adding the two missile defense systems to bolster the country’s current defenses consisting of Aegis-equipped destroyers at sea and Patriot missiles on land.

Defense officials have said the two Aegis Ashore units could cover Japan entirely from one station at Yamaguchi in the south and another at Akita in the north. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s government will now have to reconsider Japan’s missile defense program.

Kono said that Japan had already spent 180 billion yen ($1.7 billion) for the systems, but that not everything will go to waste because the system is compatible with those used on Japanese destroyers.

It was ultimately the inability to guarantee the safety of the community in Yamaguchi that was the deal breaker. Defense officials had promised that any boosters used to intercept a missile flying over Japan would fall only on a military base there, and ensuring a safe fall of boosters to the base was proving impossible with the current design of the systems, Kono said.

Japan chose Aegis Ashore over a Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense, or THAAD, system because of its cheaper cost and versatility. The deployment of THAAD in South Korea triggered protests from China, with Beijing seeing it as a security threat.

The United States has installed the land-fixed Aegis Ashore in Romania and Poland, and Japan was to be a third country to host the system.

THAAD dilemma actually not only in Japan, but also South Korea. Yoon is straddling somewhere between a hawkish South Korean nationalist and a pragmatic technocrat. During the campaign, he wrote an article condemning the Moon government's approach to Beijing, which he called so docile and wimpish that it jeopardized South Korea's national interest. Yoon was referring to Moon's "three no's" policy, designed to accommodate China after a year of hostile relations spurred by Seoul's decision to accept a U.S.-supplied THAAD missile defense system on its territory (the "three no's" included "no additional THAAD deployment, no participation in the U.S.' missile defense network and no establishment of a trilateral military alliance with the U.S. and Japan"). The decision put South Korea-China relations into a downward tailspin and prompted Beijing to curtail the China-based activities of a large South Korean retail conglomerate—costing Seoul $7.5 billion in revenue losses. The economic pain was enough of a jolt for Moon, who offered concessions to stabilize the relationship. But for Yoon, the concessions themselves were nothing short of humiliating.

Since February 24th, 2022, everything has dramatically changed. And, no one can deny that every country spends more money, after the Russia - Ukraine war. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine altered the world in 2022.

Another awkward: before Pelosi visited Taiwan, the U.S. reduced by half its FONOPS in S. China Sea in 2022, apparently to reduce tensions with China. For another example of the effect of “Pelosi Trip”, the Biden administration is plowing ahead with plans to re-open the U.S. embassy in the Solomon Islands in a bid to counter China's increasing assertiveness in the Pacific.

The State Department has informed Congress that it will soon establish an interim embassy in the Solomons' capital of Honiara on the site of a former U.S. consular property. It said the modest embassy will at first be staffed by two American diplomats and five local employees at a cost of $1.8 million per year. A more permanent facility with larger staffing is eventually envisioned, it said.

The department notified lawmakers nearly a year ago that China's growing influence in the region made re-opening the U.S. embassy in the Solomon Islands a priority. Since that notification last February, the Solomons have signed a security pact with China and the U.S. has countered by sending several high-level delegations to the islands. The U.S. closed its embassy in Honiara in 1993 as part of a post-Cold War global reduction in diplomatic posts and priorities. But it has since determined that China's rise as a regional and global power demands American attention as part of its Indo-Pacific strategy to counter Beijing, particularly in the Solomon Islands, which were a key battleground in the Pacific theater during WWII and where pro-American sentiment had been high.

Everyone, especially QUAD (US, Japan, Australia, India) plus South Korea, really worried about China.

On December 8th 2022, the Japanese government led by Fumio Kishida is considering sending advanced F-35s and other fighter aircraft on rotational deployments to Australia and expanding the scope and complexity of joint exercises, as the two seek to deepen not only bilateral ties, but also trilateral security ties with the United States.

During “two-plus-two” talks held in Tokyo (last December), the nations’ foreign and defense ministers agreed to step up both military cooperation and exchanges, announcing that Tokyo is considering welcoming Australian Air Force F-35s in Japan next year for the first time to participate in Exercise Bushido Guardian.

Building on the Reciprocal Access Agreement signed earlier this year, the special strategic partners are also considering options to conduct bilateral submarine search-and-rescue training as well as amphibious operations and guided weapon live-fire drills as part of efforts to increase interoperability and advance the scope and forms of the defense cooperation.

On December 16th, 2022, the Japanese government led by Fumio Kishida also issued new “defense guidelines” that will give the country the ability to launch offensive attacks on enemy bases overseas for the first time since its Asian empire was crushed in 1945 by the combined might of the United States and the Soviet Union.

The guidelines, fervently backed by the U.S. government and the DC think tanks representing the military industrial complex, are the last nails in the coffin of Japan’s Peace Constitution, which only allows Japan to take military action in self-defense. That document was imposed by U.S. Occupation forces after the war and has been in the cross-hairs of both the Pentagon and Kishida’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party since the 1970s.

Faced with an increasingly fraught security environment, Japan is set to beef up its military capabilities in the coming years. But its plans are being undermined by a perennial issue: recruitment.

Unable to hit its quotas since 2014, the Japan Self-Defense Forces have resorted to a variety of tactics to increase their appeal to potential new recruits. These include pop culture-based advertising campaigns, improved living conditions for recruits and efforts to create a better work-life balance.

Nevertheless, the SDF faces an uphill battle as it struggles with Japan’s falling birth rate and increased competition with the private sector over a shrinking pool of applicants.

Exacerbated by perceptions of a poor quality of life within the SDF and a postwar pacifist tradition, these personnel shortages pose a major challenge for the country’s de facto military, particularly as regional tensions surge and Tokyo sets the stage for dramatic shifts in its strictly defense-oriented policy amid growing concerns over China and North Korea.

“The enlisted corps is the backbone of the military, and the SDF feels the pain by not having enough of the soldiers, sailors and airmen needed to manage supply chains, repair aircraft and vessels, and conduct the shift work needed to operate and maintain a viable, resilient fighting force,” said a former U.S.-Japan alliance manager who requested anonymity to speak freely about the issue.

While the government recently announced its intent to double defense spending by 2027, increases in capabilities with static or shrinking personnel numbers will simply result in the SDF demanding its troops to do more with less, the former alliance manager said.

“Such an approach is unsustainable, making recruitment all the more important for actualizing Japan’s broader defense designs.”

The SDF’s current personnel target is 247,154, but as of the end of last March, the level stood at 230,754, or 16,400 short of that goal. The Ground Self-Defense Force — by far the largest of the armed services — is the most affected, with a shortfall of about 11,000 personnel.

SDF personnel planners do not benefit from a national conscription system like other advanced Asian economies such as South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore, nor a modern tradition honoring military service like in the United States.

But the main problem has been finding enough young people to fill the ranks, with the number of Japanese between the ages of 18 and 26 — long the core of the SDF’s recruitment pool — shrinking from 17 million in 1994 to 10.5 million as of October 2021, a trend that is likely to continue over the coming decades.

This pool has been further reduced by the fact that some simply do not meet the physical, psychological and educational recruiting standards for the force.

Another key factor is that Japan’s comparatively low unemployment rate has allowed high school and university graduates to be more selective about their job prospects.

While this is good for the Japanese economy, it poses a further challenge for SDF recruiters, who have to compete with private companies that often offer young adults much better incentives, be it pay, benefits, stability or more comfortable working environments.

Especially in a booming economy, the motivation to choose the SDF as an employer is lost on those who can compete in the civilian job market, said Hitotsubashi University professor Fumika Sato, who researches recruitment.

Many view SDF work as akin to a hard and dangerous “blue-collar” job that is hard to fill in the employment market, said Andrew Oros, a professor of political science and international studies at Washington College in the United States.

One of the factors contributing to recruitment in other countries is that military service tends to be a family tradition. While this has also been the case in Japan, some of that tradition has been disrupted by the falling birthrates and cultural aversions rooted in Japan’s experience in World War II, Oros noted.

That said, while the SDF had been viewed with suspicion in the postwar period — which would explain some past recruitment issues — the military is widely regarded in a different light today. Many see it as a useful institution, particularly its numerous disaster relief activities, including the SDF response to the Great East Japan Earthquake and the the ensuing crisis at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

This is why experts point to salary, working conditions and the level of public understanding of the SDF’s national security role as more decisive factors in the personnel issues.

“While the SDF is now among Japan’s most trusted organizations and can sell itself on values, values do not pay for a house, develop marketable skills or preserve employee autonomy,” the former alliance manager said.

“There is little information out there to convince a young college graduate that joining the SDF is better than getting a job at Toyota.”

Although they are national public servants with stable jobs, SDF personnel earn less than many of their military counterparts in other advanced economies, said John Bradford, a former country director for Japan at the Office of the U.S. Defense Secretary.

“This is true when comparing raw salaries, but the difference is even starker when one looks at the quality of housing, food and recreation facilities provided to them,” he added.

Perhaps more importantly, the SDF does not provide the lifetime employment opportunities associated with the larger Japanese companies, noted Bradford, who is also a senior fellow at the Singapore-based S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

Another issue lies in how many Japanese perceive the SDF’s role.

“Opinion polls show that a vast majority of Japanese have a positive view of the SDF,” said Koichi Isobe, a retired GSDF lieutenant general. “However, this does not automatically translate into more recruits.”

A key reason for this, he said, is that many still view the SDF’s main task as responding to natural disasters, not of national defense.

“People can easily imagine the role of policemen or firefighters, but when it comes to the SDF, many still have difficulties understanding what role it plays in national defense, so we need to help change that,” said the former commander of the SDF’s Eastern Army.

“A country cannot be defended by its military alone,” he added. “This can only be achieved as a joint effort with the rest of society, so the government should do more to help promote the SDF’s role and mission to the general population.”

The Defense Ministry is aware of these issues and says it has been working to tackle them.

A salary increase was implemented in 2020 and another is under consideration. The defense budget for this fiscal year, which began in April, also took aim at the issue, with the government allocating funds to improve the quality of life for SDF personnel by providing better meals, enhanced base infrastructure and improved accommodations, including child-friendly housing with playgrounds.

It has also increased support for spouses, re-employment programs and financial assistance for higher education after recruits complete fixed terms with the SDF.

The ministry is also considering adopting SpaceX’s Starlink high-speed internet communications system on some Maritime Self-Defense Force vessels to enable crew members to better communicate with their families while on long-term deployments.

Another strategy has been to carry out reforms to promote work-life balance, with the Defense Ministry saying in its latest white paper that it anticipates a “significant increase” in the number of SDF personnel with time and location restraints, including those that have child care, nursing care or other responsibilities.

“In light of these changes, the SDF is required to evolve from a conventional organization with an emphasis on homogeneity among the members, into an organization that is capable of incorporating diverse human resources in a flexible manner,” the white paper said.

These steps are also intended to help recruit more women, who currently make up about 8.3% of total SDF personnel. This year’s defense budget also includes funds to renovate the working and living sections for female soldiers in barracks and on ships, provide temporary child care services in case of emergency operations, improve workplace nurseries and promote anti-harassment measures.

Beyond continuing its recruitment activities through high schools, the force has been ramping up ads and information campaigns online, including on social media, and working closely with university career centers and local governments. It has also been targeting people looking to change jobs after raising the maximum enlistment age from 26 to 32.

At the same time, the SDF is seeking to retain personnel, raising the mandatory retirement age of colonels, captains and lower-ranking personnel by one year for each rank. It has also expanded re-enrollment after retirement — up to the age of 65 — and raised the maximum age for recruiting lower-ranked SDF reserve personnel from 36 to 54.

Nevertheless, even with the best public relations campaign and more flexible job offers, the SDF can’t reverse fundamental demographic trends.

This is why it is increasingly relying on a mix of manpower-saving measures, automation and technological innovations such as artificial intelligence-enabled systems.

In the shorter term, there are two primary effects of the SDF’s recruiting challenge, said Washington University’s Oros.

“It is going to cost more to successfully hire and retain core personnel and thus there will be an increased incentive to replace human labor where possible with new technology and more efficient processes,” he said.

Both effects are one reason Tokyo feels pressure to increase defense spending, he said, noting that Japan would otherwise simply not be able to maintain current capabilities at the present level of spending, much less increase them.

The SDF is gradually introducing AI into various fields to help with information processing and decision-making, and the force has seen an increase in the use and development of drones. In addition, future radar sites, ships and submarines and other key defense systems are being designed to reduce manning requirements.

Experts point out, though, that further automation will only be part of the solution, as the ultimate problem is not solvable through piecemeal measures.

In the meantime, the personnel shortages will continue to affect the SDF’s operational capabilities.

“Like in any business or organization, the consequences of the understaffing are that some goals must be put off and existing staff must work longer hours to cover essential shortfalls,” Oros said.

Grant Newsham, a research fellow at the Japan Forum for Strategic Studies, said SDF members tend to be overworked because they don’t have enough people in the services.

“This can make training, and especially realistic training, difficult to accomplish,” he said, noting that even carrying out essential operations is difficult since there aren’t enough personnel.

“Suppose you’re fighting a war and people get killed or injured. You need replacements. If you have too few people to start with, you have a hard time replacing casualties,” added Newsham, who was the first U.S. Marine liaison officer to the GSDF.

“Without quality officers and soldiers, the military cannot accomplish its mission, which is why we need to do more to attract more servicemen and -women and prepare them for the characteristics of modern warfare,” Isobe said.

RSIS’s Bradford agrees, saying Japan will need to invest a significant portion of its planned defense budget increase in recruitment and retention.

“Otherwise, it’s going to find itself with a high-tech but hollow force just when it needs to be hardening itself against rapidly expanding regional threats.”

The new “National Security Strategy of Japan” was spelled out in three key defense documents, and departs from the past in three critical areas. First, it declares that China is now Japan’s number one threat and poses “the greatest strategic challenges ever seen” in Tokyo. North Korea, which has traditionally been mentioned first as a hostile state, now represents a “severe and imminent threat.”

Second, it doubles Japan’s spending on its military – already one of the largest in the world – to over $350 billion, two percent of the GNP, over five years. It includes plans to strengthen the firepower of the Japanese Maritime and Air “Self-Defense Forces” (SDF) and upgrade Ground SDF units to prepare for emergency scenarios (meaning war) on Taiwan.

Third, it adopts a “counter attack” ability to hit enemy bases in China, North Korea, and elsewhere that could be applied if Japan is ever attacked.

“With the security environment surrounding Japan becoming unstable amid threats from China, North Korea and Russia, Tokyo, which has rejected warfare for the past 77 years, will be able to directly attack another country’s territory in case of an emergency,” Kyodo News explained. While the Constitution only allows Japan to act in self-defense, the National Security Strategy says the nation now needs the ability to “make effective counterstrikes in an opponent’s territory as a bare minimum self-defense measure.”

The NSS also includes controversial language that would allow Japan’s SDF to take offensive measures against any enemy force that threatened the United States. That change is “especially significant,” South Korea’s progressive Hankyoreh said, noting that the Kishida government has specified that its enemy strike capabilities could be applied not just in cases when Japanese territory is threatened but also in situations “where the U.S. is under attack.” Hankyoreh added:

For example, a North Korean attack on a US warship in the East Sea in an emergency on the Korean Peninsula could be deemed an “existential crisis,” where the JSDF would be able to strike against the North according to its “collective self-defense” rights if the US wishes. This means the possibility that peace on the peninsula could be instantly shattered by the decisions of Washington and Tokyo and Japan’s use of force, as the JSDF comes to insert itself in the peninsula’s affairs.

By further undermining the Constitution, the new policies expands the militaristic vision of the late Shinzo Abe for “collective self-defense,” a phrase that made Japan’s longest-serving prime minister a heroic figure in the eyes of Washington and leading politicians of both parties. In 2015, with strong U.S. backing, he pushed through legislation that now allows Japan’s SDF to take part in overseas military operations for the first time since World War II.

Abe’s victory transformed Japan – with its surprisingly large, tech-driven military-industrial complex – into “America’s new proxy army.” Kishida’s new policy takes that another step further, and will vastly increase US arms sales to Japan.

Before the ink was dry on the latest counter-strike documents, the Kishida government announced it will purchase hundreds of Tomahawk cruise missiles, the “flying torpedoes” that are among the most powerful and lethal weapons in the U.S. arsenal. The missiles, which are made by Raytheon Missiles and Defense, are launched from ships and submarines and “can strike targets precisely from 1,000 miles away, even in heavily defended airspace.”

The new policies were wildly applauded by the Biden administration, which dispatched its top security officials to Twitter to announced the change. First came the president: “We welcome Japan’s contributions to peace and prosperity,” he posted, calling the U.S.-Japan alliance “the cornerstone of a free and open Indo-Pacific” – a term originally coined by Abe himself. Jake Sulliven, his national security adviser, tweeted that Japan has taken a “bold and historic step.”

“Japan’s new documents reshape the ability of our Alliance to promote peace and protect the rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific region and around the world,” Secretary of State Tony Blinken declared in a special statement released by the State Department. “We applaud Japan’s commitment to modernize our Alliance through increased investment in enhanced roles, missions, and capabilities and closer defense cooperation with the United States and other Allies and partners, as outlined in these new documents.”

Just take a stroll through Twitter any day, and it’s easy to see that both the left and the right have zero interest in Japan’s new stance. And with few exceptions, the “monumental” events in Tokyo last week were barely mentioned in the mainstream media and virtually ignored by CNN and MSNBC.

The newspapers of record for the national security establishment, the New York Times and Washington Post, did run major features, but painted the changes as purely a defensive (and overdue) move by Kishida and the LDP. And in a cover-up of major proportions, they failed to mention the decades-long campaign by US military strategists to persuade Japan’s conservative government to rearm and enlist in America’s forever wars.

The Times described Kishida’s decisions as “the latest step in Japan’s yearslong path toward building a more muscular military and reducing its dependence on U.S. forces. After decades of resistance to the idea, recent polls show that over half of the country now supports at least some military buildup, amid China’s growing aggression toward Taiwan and Russia’s war on Ukraine.”

It does take a stab at outlining US pressure, but paints it as a reflection of Japan’s “maturity” as an alliance partner. The new strategy, the newspaper intoned, “was met with approval from Washington, which has long pushed Japan to take more responsibility for its own defense. Japan hosts the largest contingent of American troops overseas. Raising military spending to 2 percent of G.D.P. would bring Japan into line with pledges made by the members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.”

This is not how Japan’s military expansion was seen in Asia, however. Kishida’s new policies are not in synch with the views of many Japanese and are strongly opposed by all sides of the political spectrum in South Korea, which Biden and Blinken have been pressing to join its regional “Indo-Pacific” alliance aimed at China.

In the days following Japan’s announcement, protesters hit the streets in both countries. In Tokyo, hundreds gathered outside Kishida’s offices to lambast the LDP’s new enemy base strike capability, calling the move unconstitutional. As reported by the Mainichi:

“Military power does not create peace” were among chants that rang out from the morning in Tokyo’s Nagatacho district, as were those claiming the move goes against Article 9 of Japan’s Constitution, which renounces war…”The limits of the arms race are disappearing and danger of war is growing,” said 79-year-old Takehiko Tsukushi of Tokyo’s Kita Ward. “The United States, China and other countries concerned should find ways to compromise.”

Also protesting was a coalition of 15 groups called Heiwa Koso Teigen Kaigi, or Council on Peace Initiative proposals, which was established in October by Akira Kawasaki, the co-director of the NGO Peace Boat and other prominent activists. “There is an overwhelming lack of debate” about Kishida’s changes, Miho Aoi, a professor at Gakushuin University, declared. “We must take the issue of peace back into our hands. I strongly hope that this document will provide an opportunity for us to move forward toward building peace.”

In a stinging editorial, the left-leaning Asahi, one of Japan’s largest dailies, called Kishida’s plan a “radical and dangerous departure” from the past, and accused the LDP of “rushing headlong into beefing up the nation’s military muscle without developing plans or taking actions to improve the environment for building peace.” It also took issue with the new counterstrike capabilities, saying they would “eviscerate the nation’s long-established principle of sticking to a strictly defensive security policy. Doubling the nation’s defense spending could lead to an unrestrained military buildup.”

None of this was reported in the U.S. press.

The reaction in South Korea, now led by the ultra-conservative hawk Yoon Suk-yeol, was one of disbelief and anger. “We condemn Japan’s militaristic rearmament!” a coalition of civic groups chanted in a December 20 rally at the Japanese Embassy in Seoul. Newspapers from right to left were particularly concerned about Japan’s claim that it could unilaterally launch a counter-strike against North Korean missile launch sites without any consulation with the South.

A “counterattack by Japan of targets on the peninsula could potentially be seen as a hostile act by South Korea given the wording of the constitution, whereby all of the Korean peninsula is seen as sovereign territory,” said the conservative JoongAng Daily. It noted that Article 3 of South Korea’s constitution declares that “The territory of the Republic of Korea shall consist of the Korean peninsula and its adjacent islands.”

The Korea Times echoed that sentiment. ” The South Korean government is advised to explore ways with the United States to stop Japan from deciding on its own to carry out an attack against North Korea, an act that could infringe on the South’s sovereignty.”

The Hankyoreh, in the story quoted earlier, zeroed in on the sovereignty issue as well. “How are we supposed to accept this reality in which Japan designates the Korean Peninsula — constitutionally, our sovereign territory — as a target for preemptive strikes?” it asked. “This is especially so for the Yoon administration, which talks more about freedom and solidarity than any government.”

Not surprisingly, both North Korea and China condemned Japan’s military buildup. The Chinese Embassy in Japan said the policy change will “only stoke regional tensions” and urged Japan to reconsider that “China and Japan are partners, not threats to each other.”

The DPRK’s foreign ministry, now led by the veteran negotiator Choe Sun-hui, declared that Japan had effectively formalised “the capability for preemptive attack” with its new strategy that would bring a “radical” change to East Asia’s security environment. It also criticised the U.S. government for “conniving and instigating Japan’s rearmament and reinvasion scheme.”

In fact, behind its flowery rhetoric, North Korea is correct about the US role. The “new” Kishida policies partly originated in Washington, which has been pushing Japan to become a bona fide military power for over 40 years.