Of all of the examples of Indonesian civil disobedience on street in last 2 weeks, hanging a protest banner on the riots shields of Indonesian police cordon.

Power, or the fear of losing it, can change a leader—as argue in last 3 weeks [or actually in last 15 months] that it has changed Jokowi. But too often public are slow to recognize it, still celebrating as liberals those leaders who have long ago turned authoritarian.

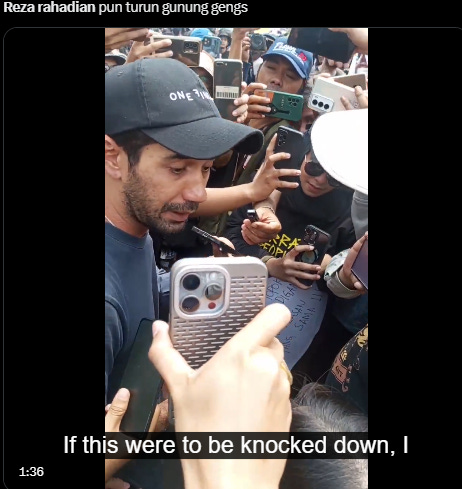

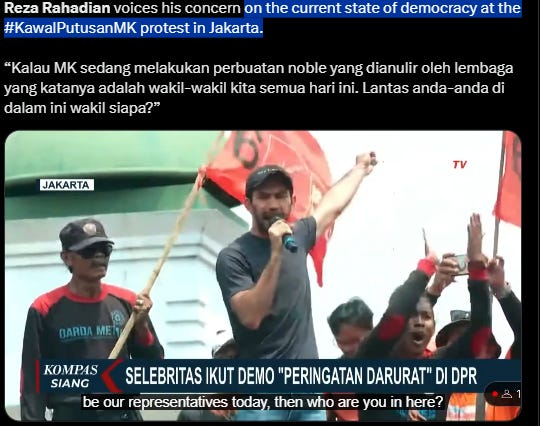

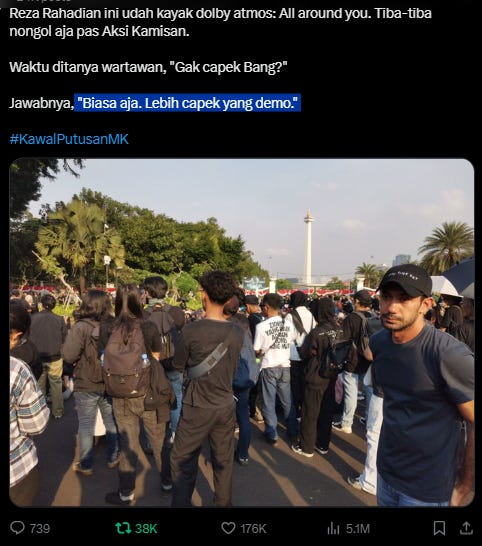

[translating actor Reza Rahadian: “Kalau MK sedang melakukan perbuatan noble yang dianulir oleh lembaga yang katanya adalah wakil-wakil kita semua hari ini. Lantas anda-anda di dalam ini wakil siapa?” [Indonesian] »> [English] Nobility of Constitution, then today we get the message that is trying to be annulled by [DPR / Parliament] institution that is said to be our representative today, the who are you in here [Indonesian Parliamentary building]?]

5.1 million views. Arguably ‘Tom Hanks of Indonesia’ and in real number of revenue, highest paid actor in ASEAN / Southeast Asia — currently the most popular Actor in Indonesia, Reza Rahadian Matulessy, join a nationwide protest in Indonesia. Reza explained that he voluntarily [in secret / unpublished, but he told to very senior Indonesia journo Rosiana Silalahi] in NGO for empowered poorest people, and also [trip secretly] to multiple secluded area in Indonesia

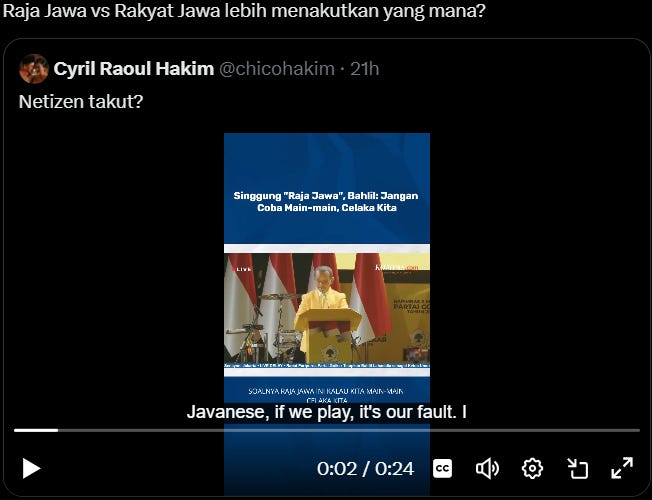

It was the kind of move that Suharto, a strongman who ruled Indonesia with an iron fist from 1967 to 1998, would have admired. Joko Widodo, Indonesia’s president, staged a hostile takeover of the late dictator’s party, Golkar, on August 21st, when its members elected Bahlil Lahadalia, the president’s fixer [aside the strongest Jokowi’s fixer, Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan] and Indonesia’s energy minister, as its chair. No one dared run against Mr Bahlil.

In a smug victory speech, the new chair warned his charges “not to play around with the King of Java”—a clear reference to Jokowi, as the president is known—adding that it would end badly for them.

[Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, one of Jokowi close ally, dubbed ‘the right-hand King of Java’, the Jokowi fixer]

Jokowi recently staged a hostile takeover of Golkar [dubbed as Indonesia’s GOP], the party of the late dictator Suharto. Bahlil Lahadalia, an ally of the president, was elected as the party’s new chair. No one dared run against him. Why did President Jokowi want to seize control of Golkar [dubbed as Indonesia’s GOP]? You have to go back to 2014, and to the near-death experience that has haunted his presidency. With no party of his own, he needs a vehicle to secure his and his family’s interests after he leaves the presidency. The chaos in DPR [Indonesia Parliamentary], as I, since October 1st, 2014 [inauguration of MP] in inside Parliamentary Building since 4am [Jakarta - local time].

Setya Novanto, former treasurer of the Golkar Partys central executive board (has been sentenced to 15 years in prison because graft), was appointed as the house speaker during a plenary session held from Wednesday (Oct. 1st 2014) until early Thursday (I remember: 5.03 am, Oct 2nd 2014, I’m present in the Plenary Room).

Like C-Span (created/installed inside the House chamber since 1979, enabling once-obscure members of Congress to reach a national audience with combative monologues that dragged on into the night) in the U.S., Indonesia Parliament has an internal media. But in a brawl (October 2014), Parliament urged every media, and even included internal Parliament media, out of the plenary room. Why am I still trapped in the plenary room just because I have ID card special guests, not “media”. So, when the brawl happened in the Capitol last night, I remember what I witnessed nearly 9 years ago in Jakarta.

Setya stepped down from his post on December 16th 2015, less than 2 years. Setya alleged multiple graft, violation of ethics.

During the ballot session, fierce debates, brawl, broke out among the politicians representing the Red-and-White Coalition of political parties and their rivals from the PDIP-backed coalition. The ballot session began on Wednesday Oct. 1st 2014, (around 4 pm, after all parliament members had sworn) and stretched on until close to dawn the next day (October 2nd, 2024, 5.03 am), after hours of fractious bickering, brawl, shouting, storming the podium and a mass walkout by nearly a fifth of those present.

Their appointments consolidate the Red-and-White coalition’s grip on the legislature as it tries to outmuscle the parties loyal to President-elect Jokowi Widodo, who faces an increasingly hostile Parliament and an uphill battle to govern.

Widodo suffered his first major political defeat, just two months before he steps down, when a popular revolt denied him the chance to field his youngest son to run in the November polls to elect the leaders of regional governments. Until last week, it looked like nothing could stop Jokowi from building his political dynasty. He controls all major political institutions, from the executive and the legislative branches to the judiciary and the police.

Public opinion was also very much behind him, going by his approval ratings in the dying weeks of his reign, with most surveys putting it at above 70 percent.

Last week, spontaneous protests by students and workers in Jakarta and other major cities took the nation’s political elite by surprise, foiling the House of Representatives’ plan to endorse a revision of the Regional Elections Law that would have allowed 29-year-old Kaesang Pangarep, the President’s youngest son, to run in one of the local elections. Kaesang’s name had been mentioned as a candidate to contest a gubernatorial election, either in Jakarta, a job his father held in 2012-2014, or in Central Java, the home province of the Jokowi clan.

Kaesang is also chair of the small Indonesian Solidarity Party (PSI), which his father secured for him last year only two days after he joined. The planned law revision would also have shut down the chance of former Jakarta governor Anies Baswedan, Jokowi’s political nemesis, to contest the elections.

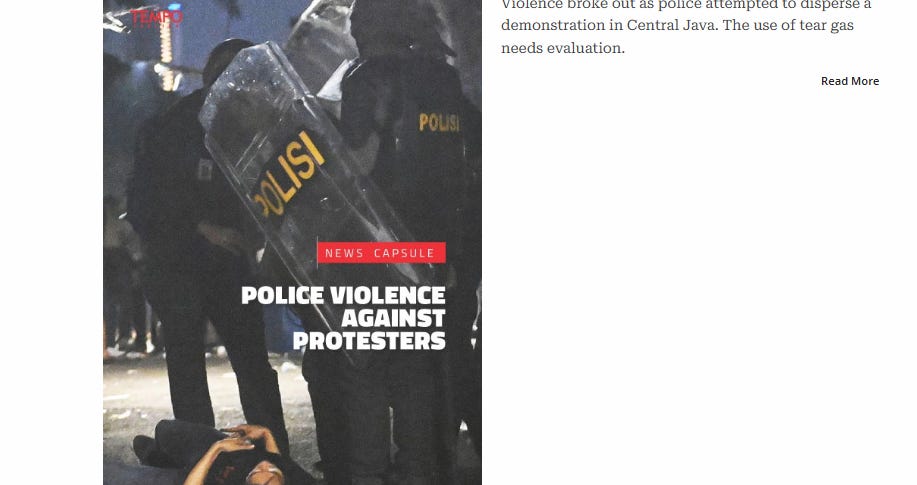

The Aug. 22 protests, some marred by violence between protesters and police, were massive, forcing the House to reverse its plan less than 24 hours after the majority factions had given support for the amendments. The House plenary meeting for the formal vote was canceled. But the real message from the protesters, openly supported by some of the country’s top universities, was not so much the planned changes to the electoral law as attacking President Jokowi’s maneuvers to use of his power to build his political dynasty that would ensure that he remains powerful after Oct. 20 when he formally ends his second five -year term.

Jokowi’s meddling included getting the Constitutional Court (MK) last year to come up with a ruling that allowed his oldest son Gibran Rakabuming Raka, despite his young age at 36, to contest the February presidential election as running mate to the eventual winner Prabowo Subianto Djojohadikusumo, who is his defense minister. The General Elections Commission (KPU) and the Elections Supervisory Agency quickly got themselves in on the act to ensure that the regulations were changed in time.

None of these institutions were found to have violated the law, but they were all reprimanded for breaches of ethics. MK chair, Anwar Usman, who is married to Jokowi’s younger sister, lost his position, although he was allowed to remain on the bench; the KPU chair Hasyim Asyari was later fired for sexual misconduct. With the MK no longer in the hands of the Jokowi clan, last week it came up with a ruling reversing an earlier ruling by the Supreme Court that set the minimum age of 30 for a new governor to be sworn in.

This move was clearly designed to accommodate Kaesang, who will turn 30 only in December. The inauguration is scheduled for January. The earlier ruling set the minimum age of 30 at the time of registering for the election, which would automatically disqualify Kaesang from running. The MK decided that the earlier ruling applied for the November election. Kaesang can still run for mayor or regent positions, which have a minimum age of 25. As part of the dynasty building, Jokowi’s son-in-law Bobby Nasution is contesting the North Sumatra gubernatorial election. A handful of other close friends and associates of the outgoing president are also contesting the November elections. Last week, Jokowi also secured control of the Golkar Party, the country’s second-largest party, by forcing its chairman Airlangga Hartato to resign, paving the way for his right-hand man Bahlil Lahadalia to take over.

Control over Golkar will wield Jokowi some influence in the next administration under his successor Prabowo, whose coalition government includes the party. But reality has sunk in that much of the power conferred on a president is slowly waning as Jokowi nears the end of his reign. The MK ruling paved the way for last week’s massive protests.

Some of the students had been prepared to occupy the House building, but they backed off after the House said it would not change the electoral law. But the episode shows that Jokowi is no longer as invincible as he has been before. It also shows that the House, in which eight of the nine parties are members of his coalition government, is no longer fully under his control. Previously, whatever legislation he wanted, he got it.

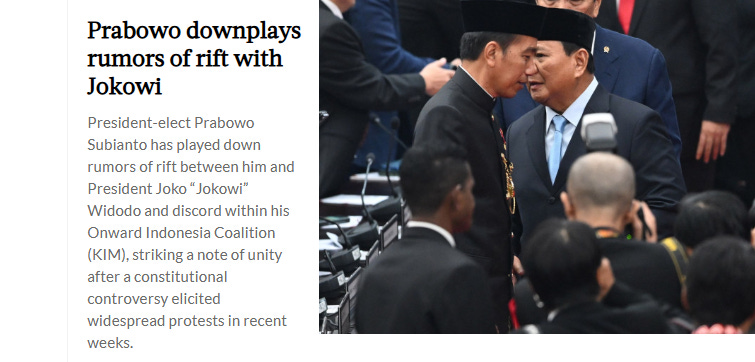

This time, Prabowo’s Gerindra Party, which had pushed for the changes in the electoral legislation, pulled the proposal. The Prabowo camp and the Presidential Palace this week were forced to come out with a statement denying any rift between the outgoing and incoming presidents. Prabowo has repeatedly pledged his loyalty to Jokowi, and promised to continue many of his predecessor’s policies. In recognition of his waning public support, Jokowi in a speech this week said, “Usually, [support] comes in droves [at the start of a presidency]. But, once it’s almost over, it also leaves in droves.”

A source in the House said one of the key figures who maneuvered to expedite the completion of this revision was deputy speaker Sufmi Ahmad Dasco. Sufmi, who is also Gerindra’s executive chairman, led the House Legislation Body (Baleg) meeting to pass the revision of the Regional Elections Law without consulting Speaker Puan Maharani of the PDI-P and another deputy speaker, Muhaimin Iskandar of the PKB. Dasco also brought Habiburohman, a member of the House's Commission III from Gerindra, into Baleg on Aug. 22 to strengthen the revision plan. The source said Dasco also asked members of the grand coalition supporting Prabowo to quickly finalize the revision of the law.

A Gerindra source said Prabowo, who just arrived from his overseas trip, was angry with Dasco for the maneuvering, which was against his wishes. “Some generals around Prabowo also disliked this maneuvering,” said the source. The source said Prabowo said he did not mind a competition among the Onward Indonesia Coalition (KIM) in the regional elections.

![Why Jokowi Shattered Our [Indonesian] Hope](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1300,h_650,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fdf1faced-3ec8-4adc-bee9-154a31568f9c_482x546.png)

![Falsehood Jakarta Method [CIA] and Toppled 'Marie Antoinette Families' in Jakarta Due to Increased Inequality, Nepotism: Tale of Regret from Indonesia and U.S.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1300,h_650,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc06628bf-5eec-4c7b-a058-99d549132dcb_565x534.png)

![Prabowo, Jewish Ally, SecDef. Austin [Ill, Critical since NYE] Best Allyin Pacific, and King Abdullah Ally - long time Palestinian Arafat friend [Review 2nd Indonesia Presidential Debate]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1300,h_650,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F306f6213-c396-4d3e-ae5f-b32d795f79cf_764x446.png)