Cost Lack of Maintenance Housing? US$1.54 billion or 4,000 times the amount builders saved, 72 lives, and thousand mental health issues.

After 6 years, no-one had been held to account for the 72 deaths. Cost cutting costs lives, costs more.

London 10.10am / DC 5.10am

Cost cutting costs lives, costs more. After the fire, the exterior was covered in a protective wrap to assist the outstanding forensic investigations. The Government, the Kensington and Chelsea Council, and the Grenfell United survivors' group, have agreed that at the conclusion of the Grenfell Tower Inquiry the demolished tower will be replaced by a memorial to the victims. Now, financial cost of the Grenfell Tower disaster has reached nearly US$1.54 billion or £1.2bn – 4,000 times the amount that was saved by replacing fire-retardant cladding with a cheaper combustible alternative during the disastrous refurbishment. In same time, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak was grilled before flying by private jet to Scotland to announce his new energy plan. Another same time, US$25.7 billion or £20bn spent, spades are in the ground but now HS2 (High-speed railway) is ‘unachievable.’ The Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA) gave the high-speed rail project a “red” rating for the construction plans for the first two phases, from London to Birmingham and then to Crewe in Cheshire. IPA’s annual report released last week states: “Successful delivery of the project appears to be unachievable. HS2 was meant to open in 2026 but it has been pushed back to between 2029 and 2033 due to difficulties with construction, numerous Government-imposed changes and mounting expenses.

Really wasting money from taxpayer.

NHS recovery unit’s response to the fire is said to be the biggest of its kind in Europe – more than £10m has been spent on treatment of the mental health of those affected. In the year after the fire, 2,674 adults and 463 children were screened for symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. Last year the St Charles Health and Wellbeing Centre was opened so that those affected by Grenfell could be treated in dedicated therapy suites. Virtual reality headsets have been used to aid in assessing ever greater numbers of people involved and hundreds of people are still coming forward for treatment. The website explaining the options available – which range from bereavement counselling to cognitive behavioural therapy to psychiatric interventions – is available in dozens of languages.

Taxpayer

The bulk of the cost is being met from the public purse, dwarfing the compensation to bereaved and survivors paid by companies involved in wrapping the west London council’s block in combustible materials before the fire in June 14th, 2017 that killed 72 people. Brexit made going to the EU a more difficult experience for UK citizens, but it didn't change anyone else's experience of the EU. Brexit made coming to the UK a more difficult experience for 450 million EU citizens. No-one had been held to account for the 72 deaths. Grenfell tragedy (June 14th, 2017) only less 1 year after the fate of brexit, UK-wide referendum on 23 June 2016, in which 51.89 per cent voted in favour of leaving the EU and 48.11 per cent voted to remain a member.

The £1.17bn known to have been spent or allocated so far is enough to fund more than 10,000 new social homes. The figure is certain to be an underestimate because several organisations involved in the disaster have not disclosed their costs.

Deborah Coles, the director of Inquest, a charity that provides expertise on state-related deaths, said: “The human cost of preventable tragedies is always paramount, but this staggering sum shows how failing to enact change when it is called for has a significant cost to the public purse because death is expensive.

To compare with West London, and to show how tragic:

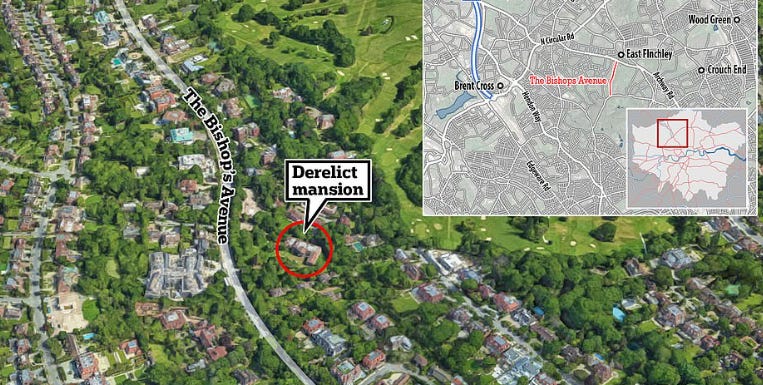

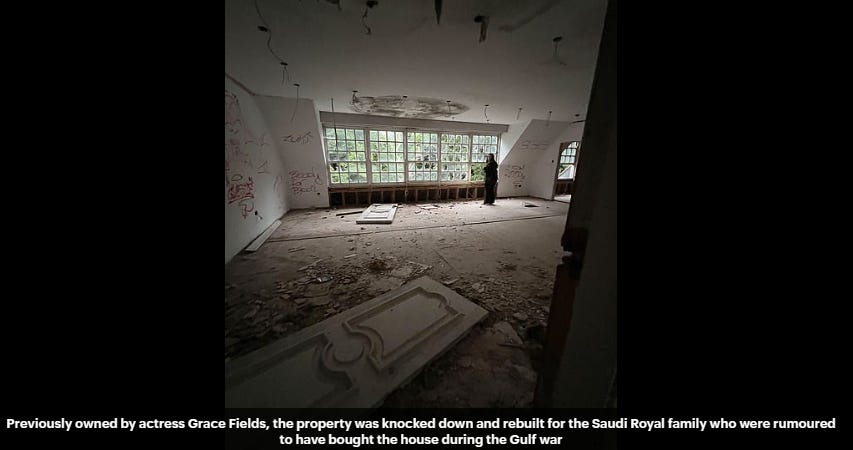

Student 'urban explorers' snuck into a dilapidated Georgian mansion on north London's Billionaire's Row - where homes have a combined worth of around £511million, one of the wealthiest streets in the world. Bishops Avenue, located between the north side of Hampstead Heath and East Finchley, consists of 66 mansions whose former inhabitants have included the super-rich Sultan of Brunei and the Canadian pop superstar Justin Bieber.

The site of the property, which is known by locals as 'The Towers' and is thought to have been abandoned for decades, was first owned by British actress and music hall legend Gracie Fields before it was knocked down in the 1970s.

The current mansion then took its place, and was reportedly snatched up by the Saudi royal family during the Gulf War for an estimated £25million.

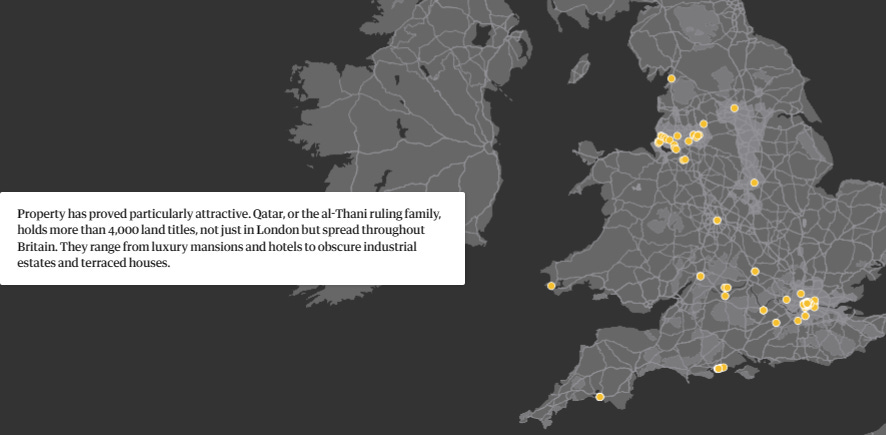

Qataris’ British (not Saudi) property empire has ballooned since then into a sprawling portfolio likely to be worth in excess of £10bn.

Qatar and the vast al-Thani clan that rules it have played a real-life game of Monopoly, scooping up trophy assets such as hotels on Mayfair and Park Lane – not to mention properties on Pall Mall, Oxford Street, Bond Street and Vine Street. Prize purchases include ultra-high-end hotels such as the Ritz and Claridge’s, the international finance hub at Canary Wharf, not to mention luxury personal retreats, including rural idylls and London mansions.

The state of Qatar alone, not counting individual royals’ personal holdings, is the 10th largest landowner in the UK, according to analysts at MSCI Real Assets. The emirate owns nearly 2.1m sq metres (23m sq feet) of property in Britain, more than 1.5 times the area of London’s Hyde Park.

Many of the properties are owned through Jersey, the British Virgin Islands or the Cayman Islands, meaning ownership is often difficult to determine via public disclosures.

It's hard to walk round London and admire the sights without admiring something paid for by Qatar.

From some of the most famous hotels and landmarks to the cranes arcing over the South Bank, Qatar has a substantial finger in a huge number of pies.

The UK is Qatar's single largest investment destination, with £35bn in place and another £5bn on its way in the next five years.

Taxpayer

Back to Grenfell.

Retired firefighters from across the country have reported mental health problems despite not even attending the Grenfell fire disaster.

The Fire Fighters Charity revealed that the harrowing TV images alone had been enough to trigger mental health episodes and force retirees outside London to seek their help.

It comes as the charity launches a new video to highlight the scale of mental health problems for firefighters after dealing with extreme and repeated traumatic situations.

A recent report by the Chief Fire Officers' Association found 41,000 shifts a year were lost in England and Wales due to mental health issues suffered by firefighters.

Dr Jill Tolfrey, of The Fire Fighter's Charity, explain: "These are invisible injuries, often carried by firefighters in silence.

"However, they can have far reaching, long term consequences, affecting families and family life and, if ignored, potentially leading to depression, self-harm or even suicide."

The chief executive added that the Grenfell Tower inferno has had an enormous impact beyond the London Fire Brigade.

Taxpayer

She said: "We had retired firefighters telephoning us, saying the events they had seen on television had stirred memories from when they were working... so the memories they take with them in their firefighting career actually go into retirement as well."

Nabil Choucair, who lost six members of his family in the fire, described the difference between the overall costs so far and the £150m settlement to bereaved and survivors as a disgrace.

“If they had spent a fraction of this money before the fire and listened to us families, this disaster wouldn’t have happened,” he said. “They tried to make savings at the price of our families and now we are paying that price through our suffering. We all pay for their mistakes at the end of the day.”

£469m has been spent or budgeted for its Grenfell response by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, which owned the tower and authorised cost-cutting decisions that contributed to the scale of the disaster. A large part of this was required to buy new homes for survivors.

£291m has been allocated by central government for costs associated with its ownership of the site, which will become a memorial.

The public inquiry and police investigation, neither of which have yet concluded, have so far cost a combined £231m.

Arconic, which made the combustible cladding, has spent £35m on lawyers and other advisers, and it recorded a liability of £47m in its accounts for settling civil claims.

Close to 900 bereaved and survivors have so far received £150m in compensation through civil court proceedings, a figure confirmed in the latest annual accounts of the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities.

The figures come as high court compensation negotiations continue involving dozens of firefighters, police officers and other claimants. A £50m “restorative justice” programme is under way using money obtained from Arconic, the council and others. The council says this “will take the form of the delivery of services to the bereaved and survivors and the immediate community”.

The Grenfell Memorial Commission, which is steered by 10 community members, will this autumn announce its preferred plan for the future of the burnt-out tower. A memorial garden is considered a likely part of the outcome. Meanwhile, companies and organisations that are likely to be criticised in next year’s final public inquiry report have been formally asked for their responses.

The financial consequences of the fire stand in contrast to the money saved in 2014 when the council’s landlord body chose the cheapest contractor’s bid and then shaved £700,000 off that in a “value engineering” exercise. It saved £293,368 by swapping zinc cladding for an aluminium alternative with a combustible polyethylene core. The council has told the inquiry that “cabinet members were never advised that additional expenditure was necessary for safety reasons”.

“Think what this money could have done in terms of preventing deaths,” said Coles, who is calling for a national oversight mechanism to ensure official recommendations for change after contentious deaths are enacted. “We could have proper escape protocols for people living with disabilities, which were rejected by the Home Office partly over cost; removing dangerous cladding and building safe housing.”

The police investigation, which Scotland Yard describes as one of the largest and most complex it has undertaken, has cost more than £60m to date. Operation Northleigh has taken more than 11,000 witness statements and detectives are still working through 130m documents, a Met police spokesperson said.

In total, 40 people have been interviewed under caution as 180 investigators examine possible corporate manslaughter, gross negligence manslaughter, fraud and health and safety offences. No one has yet been charged.

Asked to comment on the cost of the disaster to the council by contrast with the saving from the cladding switch, the council’s leader, Elizabeth Campbell, said: “Our continuing priority is to support the bereaved, survivors and the local community, from providing the help and support people need to the recent resolution of the claims process – an important juncture for those affected … We are committed to learning from the Grenfell tragedy and doing right by the bereaved and survivors.”

The council said it planned to pursue claims “against the other parties also responsible for this tragedy for a share of the costs incurred from the public purse”.

The public inquiry alone has so far cost £170m, not including the legal costs of the companies and organisations involved in the refurbishment that led to the fire.

Rydon, the main contractor, has set aside up to £27m for civil claims, its latest accounts suggest. The London fire brigade has spent £14.5m on legal bills.

In a statement, the Met police said if detectives concluded there was sufficient evidence to consider criminal charges after they had fully examined the findings of the public inquiry’s final report, due next year, a file would be submitted to the Crown Prosecution Service. That suggests charges, if they follow, could come in late 2024 or even into 2025, with trials following later.

“We can only imagine the impact on families of a long and complex investigation and public inquiry and we do understand their frustrations,” a spokesperson said.

Ministers face further setbacks over their plans to house migrants as all three mass accommodation sites are beset by problems.

The Bibby Stockholm barge, which was to accept its first 25 asylum seekers tomorrow, has yet to receive approval from the local fire service amid fears it is a “death trap”. It is one of three large-scale sites at which the government intends to accommodate migrants, to cut the cost of housing them in hotels, which is running at more than £6 million a day.

Another site is RAF Scampton, the former Dambusters headquarters in Lincolnshire, which also faces problems. Plans to move in 2,000 people have been delayed until October because the Home Office failed to find people to survey 14 buildings that it wants to use.

Tomorrow the Home Office will move 50 more migrants into the former RAF Wethersfield site, despite scabies, tuberculosis and scurvy among the first 46 who arrived this month.

Up to 506 migrants will be housed on the Bibby Stockholm barge, which is docked in the Port of Portland in south Dorset, despite it being built for only 222 people. An additional 40 staff will also be on board when the barge is at full capacity.

A whistleblower in the local authority said fire safety checks last week led to serious safety concerns. They described the barge as having the potential to become a “floating Grenfell” due to the lack of fire safety protocols. The barge has 222 cabins of long, narrow corridors over three decks, with only two main exits.

Another local source said Dorset & Wiltshire Fire and Rescue Service was “very critical on a number of safety issues” after inspections last week. The source expressed fears that the Home Office would “suppress” the safety concerns raised to progress its plans to move migrants on board.

A protester stands outside RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire. The Home Office has failed to find people to survey the buildings it wants to use

MARTIN POPE/GETTY IMAGES

Landry and Kling, the management company, told The Times that it would not be carrying out fire drills because it did not want to upset migrants on board as they may have faced “traumatic situations” on their journey to Britain.

The evacuation point for those on board is a compound on the quayside, described as “completely inadequate” for 550 people by someone who has worked at the port. There have also been warnings of a “Hillsborough-type crush” as it is behind two sets of locked security gates.

Councillors who visited the barge last week were told there are no lifejackets on board, and refurbishment was required to repair rotting on the hull.

Graham Kewley, the fire safety manager at Dorset & Wiltshire Fire and Rescue Service, said it had provided “advice and comment” on fire safety to the Home Office and the vessel’s operators after inspections last week, adding that the service would use enforcement powers to address “any significant areas of non-compliance where necessary”.

The Home Office has confirmed that fire safety checks were continuing but said that all safety regulations would be met before asylum seekers moved on to the site. The Times understands that the department is still planning to put the first 25 migrants on board tomorrow.

Officials are confident that fire safety procedures will not be breached when a small number of migrants are on board because the fire service’s concerns related to when the barge reaches full capacity.

This month the Home Office said it was on course to move 2,000 asylum seekers into repurposed buildings on the RAF Scampton airfield by the end of next month. However, the first migrants will not move in until October at the earliest because of a failure to carry out required “intrusive surveys” on the 14 buildings it plans to use.

There have also been delays in finding qualified workers to assure gas, water and electricity connectivity to the site. This shortfall has delayed the transfer of the site from the Ministry of Defence to the Home Office.

It has left the Home Office with only one functioning mass accommodation site, at the former RAF site of Wethersfield in Braintree, Essex. A further 50 migrants are due to be moved into the site tomorrow despite scabies, tuberculosis and one case of scurvy being found among migrants who were moved there on July 12.

Nicola David, from the One Life to Live charity who has been tracking the progress of the Home Office’s plans to use the Bibby Stockholm barge to accommodate asylum seekers, said the vessel was a “disaster waiting to happen”.

She said: “All of my research, and everyone I’ve spoken to, indicates that the overcrowding on the barge, and the rot found in the hull during its time in dry dock, render the barge entirely unsafe from the point of view of additional weight and inherent fire risks. Add to this the extremely narrow corridors, windows that can’t be used for escape, no lifejackets, no fire drills, and a tiny and inescapable evacuation compound surrounded by insurmountable fencing and locked gates.

“In an emergency, the sense of panic could only be heightened by smoke, potentially dim emergency lighting, disorientation, and — for those without sufficient English — an inability to respond to verbal instructions. I just don’t see how everyone could get off the barge, or be immediately safe once of the barge, in the event of a serious fire or a sudden ingress of water. Bibby Stockholm feels like a disaster waiting to happen.”

Priti Patel, the former home secretary who represents the neighbouring seat of Witham, has called for further arrivals to be halted, adding: “The Home Office has ignored local concerns over health screening, and this has led to scabies and TB being found.”

A Home Office spokesman said: “The Bibby Stockholm is undergoing final preparations to ensure it complies with all appropriate regulations before the arrival of the first asylum seekers.

“The Home Office is working with stakeholders on a carefully structured plan to increase the number of asylum seekers at Wethersfield.”

November, Amina Thomson, who describes herself as a faith-based psychotherapist, was having lunch in the kitchen cafe at the al-Manaar Muslim cultural heritage centre in north Kensington. After the fire at Grenfell Tower half a mile away in June 14th, 2017, the basement kitchen had become recognised as the heartbeat of the local community, as it tried to cope with the ongoing aftershocks of the tragedy in which 72 people died. Meghan Markle had helped to launch a bestselling charity cookbook with the women who volunteered there each day.

The kitchen may have become a byword for resilience and compassion, but that lunchtime Thomson, 55, a quietly spoken and bright-eyed presence, was listening to a conversation at a neighbouring table and feeling that something was not quite right. A woman bereaved in the Grenfell fire was sobbing and her friends, sitting with her, though sympathetic, were insisting she dry her eyes, saying that the time for tears had passed.

Thomson, who had been counselling some of the bereaved, was prompted by watching that exchange to offer a new type of group therapy at the mosque, the basic message of which was that it was “OK for Muslim women to cry in public”. The group of about 30 women who started to come along, all directly or indirectly traumatised by the fire, has now met every Friday for six months. One of the regular attendees, who lost her home in the shadow of Grenfell and still lives in a hotel, explained to me how it had been considered taboo among some women to admit to psychological problems in the two years since the fire. “So many people are in need of help, but they don’t know what they need,” she said. “In my community they do not always understand mental illness or depression. It is seen as not normal.”

Thomson started the first session by reading with the group a story from the Qur’an in which the prophet Yaqub cried until he lost his eyesight after his son was taken from him. “Some people here think that being a Muslim means that you should accept suffering and not complain about your distress, but that is not right,” Thomson told me. “The prophet was asked why he was crying, and he said, ‘I’m crying because I’m a human being’. He had lost his son. If prophets can cry, then we can cry too.”

Thomson calls her model of therapy “heartfulness” because it insists that a balance of mind begins to be restored by the “tranquillity of the heart”: to be induced by good breathing, diet, rest, exercise and prayers – dhikrs — that help “remembrance of Allah”. She subsequently uses Qur’anic texts with which the women are familiar to open discussions about trauma. Talking about the detail of this practice Thomson, Moroccan by birth, jumps quickly between noted psychologists and Islamic prophets, between attachment theory and Allah. “Women have started coming here out of their homes,” she says, “where before they were quite isolated. Some are psychiatric patients. Some have directly lost people – in one case a whole family has gone and the mother comes.”

At the end of last month, Thomson invited me to join one of those sessions in the upstairs library at al-Manaar. The women did not feel comfortable with a man being present while they went through the initial exercises that involved breathing and prayer and massage. By the time I came in they had moved on to the day’s story, which concerned the death of Muhammad’s uncle, Abu Talib, and “the year of grief”. In the early sessions the women had apparently been reluctant to open up to the group about the feelings a story gave them, but now, at Thomson’s encouragement, they first talked in small groups and then to the room.

I was surprised to note that the traumas they dwelt on were mostly rooted not in the here and now of their lives after Grenfell, but more often in the countries many of them had left behind: Syria, Libya, Eritrea, Somalia. In relating the text to wars that they had escaped, in which their families were lost or still suffered, several of the women wept and no one suggested that they should stop.

“Jean Piaget, [the developmental psychologist] calls those moments the schemas,” Thomson said to me later. “They are the moments when you can change the narrative. We collect them and build on them each week.”

The session in the mosque offered a tiny window into what, two years on, is the ever-growing legacy of the Grenfell fire. When the flames had finally been extinguished following that terrible night, the aftermath first looked like a crisis of governance and organisation, then one of care and housing; it now registers increasingly as a mental health disaster. The scale of that trauma – impossible to fathom among those who escaped from the tower or lost loved ones – has been greatly amplified by the fact that many people who lived in the vicinity of Grenfell had in childhood fled from conflict or terror. For those one-time refugees, the unavoidable sight of the inferno, and the chaos and displacement that ensued, made all sorts of buried nightmares resurface.

For many of the people Thomson deals with, Grenfell was only the latest disaster to befall them. “A lot of people have come from different traumas and the fire is the last straw if you like. It has come in a place where they thought they were finally safe,” Thomson says. She smiles a little wearily. “Each day, I find myself now in the middle of the Somalian civil war, the war in Lebanon and Iraq and Eritrea and Sudan.”

For a few hours in Thomson’s company as she made her round of visits I felt first-hand what she meant. The first two of her patients that we met, whose stories are told at greater length below, had both escaped from Somalia during the civil war. Ifrah Abdiguled, 53, had lost her two infant children in that conflict. Mourad Haad Hussin, 45, had seen his whole family murdered. Now here they were, 20 years later, trying to piece back together once again their shattered emotions. Others we spoke to remain too traumatised to be identified by name. One young man, who lost his wife in the fire, decided he did not wish to tell his story to me; instead he laid out in front of me page after page of drawings he had made obsessively in his wife’s memory. Another woman, who at the time of the fire was in hiding from her abusive husband, still lives in fear of him finding her. She explained how, after arriving in London as a refugee she had married a man who routinely beat and choked her and finally threatened her with a gun. She showed me the scars on her arms and neck. Her place of refuge had been in a flat next to Grenfell. After the fire she had slept for four nights in a car, before being housed in a series of hotel rooms which she was frightened to leave at night. She lives in hope of a permanent place so that at some point she might be able to resume her work running a team of carers. Her therapy with Thomson, she believed, was slowly rebuilding her broken confidence. “I used to earn £3,500 a month,” she said, crying quietly. “Now I have £200.”

Thomson shoulders a lot of these people’s problems herself. Though all of them have used, and often been grateful for, the services offered by their GPs and by the therapies at St Charles hospital, they say they find more relevance, and more trust in a model based on the faith that sustains them. As a result, Thomson has also found herself helping with the range of issues – housing, income, residency – that for two long years have exacerbated all of her patients’ anxieties. “I have never written so many letters,” Thomson says. “Letters to lawyers, letters about housing, letters to the MP, particularly Emma Dent-Coad, who has been very helpful.” While we drive between bedsits, Thomson explains that she comes from a long line of healers. She herself eventually came to the work after experiencing all the stages of trauma as a 15-year-old, when three family members, including her father, died in a car accident.

Thomson’s work not only appears effective as a solace for the people I meet, however; it also – like so many issues starkly highlighted by the tragedy – raises complex questions about the relationship between local authorities, national government and community organisations, and their responsibilities to the most vulnerable. The charity Muslim Aid has been funding Thomson’s programme, though that money is set to run out in September. The charity, whose staff were among the first responders on the ground at Grenfell, published a telling report last year on the disaster, called Mind the Gap. It made the case for a far greater involvement of local community groups in planning for such tragedies and for effective collaboration between secular and faith-based organisations in responding to them.

A year on from that report, the charity sees the mental-health crisis that has flowed from Grenfell Tower as a case in point. One of the report’s authors, Lotifa Begum, was among the first on the ground at Grenfell on the morning of the fire. She recalls how the flailing local authorities failed to ask for the help of humanitarian agencies to deal with the problems – though clearly an organisation like Muslim Aid, with experience of disaster response elsewhere in the world, and with deep links to this particular community, could have been invaluable.

In the event, Begum helped to establish, along with representatives of three other charities, the Grenfell Muslim Response Unit, which worked alongside the authorities. “The council key workers were a bit lost in knowing how to help these families,” she says. For a start, they had limited knowledge of Muslim burial practices, which were an urgent, heartbreaking issue; language was, and remains, a problem. “One incident will stay with me for the rest of my life,” Begum says. “News had been delivered to an Afghani lady that her husband had passed away in the fire. She was wailing in the corridors of the relief centre and beating herself up, literally, because in Afghani culture, that is how they grieve. The council workers were astonished, they had no idea what to do. I eventually found a Farsi translator and we got her a room.”

Two years on, Begum believes that the reluctance of the local authority to properly engage with what their citizens need is seen in the response to Thomson’s Heartfulness project. It obviously, and correctly, lies beyond the secular remit of the NHS to use religious frameworks to deliver therapy. However, there is a strong case for working with any such programme that can be shown to meet a complex need. In the next council funding round, however, Kensington and Chelsea has cut its grant for counselling services to al-Manaar by 10%, even though it has played such an expansive and pivotal role in supporting the Grenfell community. That cut will make it all but impossible for the centre to take on the cost of Thomson’s programme as she had hoped, when the current funding runs out. “I think there has to be an understanding that NHS and faith-based, community-based therapies need to be working hand in hand,” Thomson herself argues. “Faith and culture are clearly extremely important to these people and that is the language and the context which they understand.”

At the end of our day sitting in bedsits and hotel lobbies meeting those people still adrift in Grenfell’s great disruption, Thomson suggests that she doesn’t know how she will carry on providing her support to those desperate souls, though she knows she must. And for the first time she wipes away a tear herself.

Mourad Haad Hussin, 45, met us outside his studio flat. He has been receiving counselling from Amina Thomson for six months. While we talked his television was tuned to a channel in Arabic in the background. His English was heavily accented, but he was very anxious to make himself clear, so he repeated phrases until I understood them. After the Grenfell fire he was diagnosed with schizophrenia and given medication.

“My story begins when I was 14, in Somalia. One day I was playing football and four or five army cars come to my house. My family was in the house so I ran there and I hear ‘Boom! Boom! Boom!’ I come in and see my cousin, my brother, my uncle’s body. Blood everywhere. My father is by the window and he throws me through it, like that, and he says ‘Run! Run! Run!’ Later we have to come back to the house and I see my father dead in the road. They shoot him in the leg and they run him over. My mum is there crying and our whole family is gone.

“That was 30 years ago. We stayed two nights at the house and then me and my mum walked to Ethiopia, 10 days. We walked at night because the days were too dangerous. One night the war came to the place we have stopped and they kill 400 people, 500 people. I lie in a hole and they start throwing bodies on top of me and I am trapped like that until they pull me out.

“My mum and I stayed in Ethiopia for four years. Somalia became a little bit more normal and my mother sold our house and used the money to send me here. She says: ‘Run! Run! Run!’ I worked in different jobs in London. Sometimes a kitchen porter, Claridge’s kitchen. Sometimes in laundry, operating washing machines. I am alone, but when my mum is alive I don’t need anyone. We call each other every night and every morning. But now last year she is gone too. If I was not a Muslim I would kill myself, but the Qu’ran says I cannot do that if I want to meet my family again - and I want to meet my family.

“The night of Grenfell I got up early for my pre-dawn Ramadan meal at two o’clock. My pasta was ready when I saw the fire and I ran out there. The police are pushing, pushing, pushing. And the fire just goes up the side of the tower, whoosh like water. I looked up and I saw three boys at the window up there with the fire. People are shouting ‘Run! Run! Run!’ but they cannot run. I am there two days, two nights trying to help people. I can’t go home. I can’t sleep. I see the fire and I see the boys at the window.

“I sleepwalk every night; I have to hide my key in the washing machine. I wake up in the shower. My GP was kind; she says, your family were in the tower. She knows my story. And after I went to Amina and now I pray for Fridays when I see her. She is good with psychology, she knows the Qu’ran. I want to get back to who I was before. They tell me to cry. Allah wants me to cry.”

On the morning I met Ifrah, 53, she had just – after a two-year struggle since she left her home beside Grenfell Tower – been housed in a basement flat in Earl’s Court with her daughter, Fatema, 12. They were yet to unpack. Ifrah had come to the UK as a refugee from Somalia in the 1990s – her first two children, one six months old, and one aged two, had died during the bombing and famine of the civil war.

“I have lived in London for 25 years. I always had lots of jobs, as a carer and as a cleaner. I lived in Whitechapel to start with then nine years ago I moved to a place right opposite Grenfell Tower. My daughter was at primary school there. We saw our friends at the swimming pool the previous day, we went to sleep that night and we wake up and it was just unbelievable that they were gone. My daughter had a friend who lived in that tower. She was shouting ‘Hafsa! Hafsa!’ over and over. We saw the people falling and everything and that started my stress and all the memories. It was the same as in Somalia: one minute you were sleeping and then you wake up and you had no idea what was going on. All my windows were facing the tower. I could not go back.

“We were put in a hotel near Waterloo for seven months. Then they found us a place in Shepherd’s Bush, but the antisocial behaviour was so bad. Seven people had moved out before us, I was told. It was music all night and people dealing drugs and swearing right up to your face. They threw dog’s excrement through my window, lighted cigarettes. That was the worst time. I went to hospital, I was sectioned. Fatema went to live with my sister and I went to hospital for seven weeks with post-traumatic stress disorder.

“We still had nowhere to live. They offered us a place in Hounslow, then one in Wembley, but they were too far from school for my daughter. They wanted me to sign something to say that they had offered two places and I had refused so that was it. Amina helped us a lot. She put me in touch with the MP Emma Dent Coad. And eventually we got this place.

“When I come to this country my mind was always going on back home to my children. It took me years to get past that. But at least I felt safe here – until that night. My daughter lost her friend Hafsa. She had two classmates that lived in the building. I take her to school, she doesn’t like going on her own. It is maybe 40 minutes from here. When I get off the bus I always go around so I don’t have to see the tower.”

If you are having thoughts of suicide, call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, or go to SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for a list of additional resources. Bit different but still related/potential to suicide, the domestic violence hotline is 1-800-799-SAFE (7233). In the UK, call the national domestic abuse helpline on 0808 2000 247, or visit Women’s Aid, or can access help and resources via www.rapecrisis.org.uk or calling the national telephone helpline on 0808 802 9999. In Australia, the national family violence counselling service is on 1800 737 732. Other international helplines may be found via www.befrienders.org.

=========END============

Thank you, as always, for reading. If you have anything like a spark file, or master thought list (spark file sounds so much cooler), let me know how you use it in the comments below.

If you enjoyed this post, please share it.

If a friend sent this to you, you could subscribe here 👇. All content is free, and paid subscriptions are voluntary.

—————————————————————————

-prada- Adi Mulia Pradana is a Helper. Former adviser (President Indonesia) Jokowi for mapping 2-times election. I used to get paid to catch all these blunders—now I do it for free. Trying to work out what's going on, what happens next. Arch enemies of the tobacco industry, (still) survive after getting surreal-sophisticated doxed. For me, justice is a difficult dream, because (ex) my friend, hundred, cooperate each other, to kill me and my mom. Don't let the bastards get you down, Prada, some my close friend support me. If Kevin Spacey and Johny Depp finally free from accusation, maybe next is my chance. i refuse to sacrifice my peace and comfort just to keep someone in my life. i refuse to allow consistent disrespect from someone just to keep them in my life.

Now figure out, or, prevent catastrophic situations in the Indonesian administration from outside the government. After his mom was nearly killed by a syndicate, now I do it (catch all these blunders, especially blunders by an asshole syndicates) for free. Writer actually facing 12 years attack-simultaneously (physically terror, cyberattack terror) by his (ex) friend in IR UGM / HI UGM (all of them actually indebted to me, at least get a very cheap book). 2 times, my mom nearly got assassinated by my friend with “komplotan” / weird syndicate. Once assassin, forever is assassin, that I was facing in years. I push myself to be (keep) dovish, pacifist, and you can read my pacifist tone in every note I write. A framing that myself propagated for years.

(Very rare compliment and initiative pledge. Thank you. Yes, even a lot of people associated me PRAVDA, not part of MIUCCIA PRADA. I’m literally asshole on debate, since in college). Especially after heated between Putin and Prigozhin. My note-live blog about Russia - Ukraine already click-read 4 millions.

=======

Thanks for reading Prada’s Newsletter. I was lured, inspired by someone writer, his post in LinkedIn months ago, “Currently after a routine daily writing newsletter in the last 10 years, my subscriber reaches 100,000. Maybe one of my subscribers is your boss.” After I get followed / subscribed by (literally) prominent AI and prominent Chief Product and Technology of mammoth global media (both: Sir, thank you so much), I try crafting more / better writing.

To get the ones who really appreciate your writing, and now prominent people appreciate my writing, priceless feeling. Prada ungated/no paywall every notes-but thank you for anyone open initiative pledge to me.

(Promoting to more engage in Substack) Seamless to listen to your favorite podcasts on Substack. You can buy a better headset to listen to a podcast here (GST DE352306207).

Listeners on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Overcast, or Pocket Casts simultaneously. podcasting can transform more of a conversation. Invite listeners to weigh in on episodes directly with you and with each other through discussion threads. At Substack, the process is to build with writers. Podcasts are an amazing feature of the Substack. I wish it had a feature to read the words we have written down without us having to do the speaking. Thanks for reading Prada’s Newsletter.

Headset and Mic can buy in here, but not including this cat, laptop, and couch / sofa.