Kompas, Tempo, Media Indonesia, Jakpost, Jawa Pos, and also all online media are not even published again about the May 12nd, 1998 riot today. My friend Riri celebrate birthday today — and even I joked to her that I really CANNOT FORGET her birthday because.. “a riot.”

To “commemorate” May 12nd 1998 riot, 10 years after riot, UGM with alot universities, set a mass protest in Jakarta, May 12nd, 2008. Assume we from UGM reaches 1,100 students, from Yogya to Jakarta, not counting several universities in Yogya and Central Java joining us.

Batavische tribe (Betawi), Java, Sunda, Minang, some Madura, burned in a lot mall in Jakarta and several cities in Indonesia. “Kraton” (Palace) in Surakarta has burn at least 30%. Because Soeharto Inc (Cendana family) PLUS Soedono Salim, combined 2 families, conquered almost 60% Indonesia GDP, Chinese overseas get attacked across Indonesia. Chinese overseas are identically with elite-(crazy) rich since a long time ago, not only 1990s, and not only today. But again, the poorest, mid-low income, Betawi, Java (Jawa), Sunda / Sundanese etc in Jakarta had been burned in several malls and traditional markets. Shops were looted and goods burned on the streets in Jakarta and several cities. I still remember Pasar Johar (I’m in Semarang when the riot happened) also burned, plus “Matahari Johar” (across Pasar Johar/Traditional Market Johar) got looted too.

Jakarta descended into violent chaos and destruction overtook the city. At the conclusion of the May 1998 riots, thousands had been burned or beaten to death, over a hundred ethnically Chinese women had been raped, and a large part of the city had been destroyed. All non-essential U.S. personnel were evacuated by US Marine (*The US Marine site in Jakarta is beside Aryaduta Hotel — around 400 meter from the US Embassy). The US government has a fetish to make sure the Embassy must be “too near” with the Presidential / Prime Minister / Chancellor / Kingdom / Sultanate / Emirate office. Students occupied the parliament building in a series of protests that brought about the resignation of then-President Suharto.

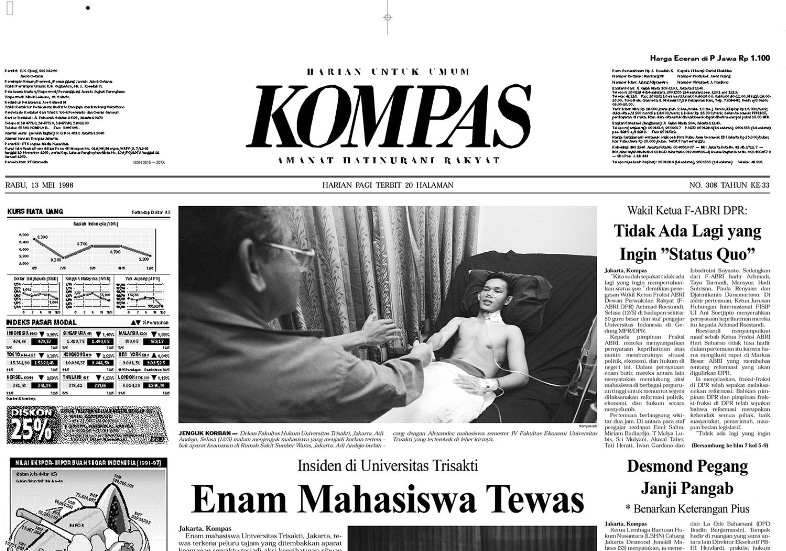

(Very hard to repair credibility after riot ——Sulit Pulihkan Kredibilitas Pasca Kerusuhan. Newspaper May 13rd, 1998, one day after May 12nd, 1998)

(photo for frontpage/headline by Pak/Mr Arbain Rambey, veteran journalist)

(via Pak/Mr Arbain Rambey)

(via Mr/Pak Arbain Rambey)

(via Pak/Mr Arbain Rambey)

(Firdia Lisnawati)

The people of Indonesia had been suffering from the Asian Financial Crisis. Suharto’s regime “The New Order,” which had remained strong for 32 years, was severely damaged by rampant corruption and its inability to maintain economic stability. Nationwide student demonstrations in support of democracy called “Reformasi” (reform) spread rapidly.

(Promoting to more engage in Substack) Seamless to listen to your favorite podcasts on Substack. You can buy a better headset to listen to a podcast here (GST DE352306207). Listeners on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Overcast, or Pocket Casts simultaneously. podcasting can transform more of a conversation. Invite listeners to weigh in on episodes directly with you and with each other through discussion threads. At Substack, the process is to build with writers. Podcasts are an amazing feature of the Substack. I wish it had a feature to read the words we have written down without us having to do the speaking.

On May 12, the death of four protesters at Trisakti University provoked mass rioting and looting targeted at ethnically Chinese individuals and businesses. Allegedly instigated by the Indonesian military, this violence was largely separate from the student movement that resulted in Suharto’s resignation a week later. The Indonesian Revolution was a success, but Suharto’s successor Vice President B.J. Habibie was not the reformer the protesters had wished for and violence against the Chinese left a lasting legacy of pain.

Students Protest Against KKN. This was the Suharto era. He’d been in power for 30 years. We didn’t know what was going to happen, but it felt like it could be getting close to the end of that era. . . . [F]rom late 1996, it seemed that the students were starting to get politically active.

. . . . Indonesia had numerous legal youth and student “mass organizations”. . . . They’d issue statements and they’d hold meetings and conferences and they would talk about and call for political reform, openly. That’s what they were pushing for. And they were protesting against “KKN”— corruption, collusion and nepotism. . . . By the spring 1998, you could get t-shirts that said things like “No Suharto, No Habibie, No KKN.” People were talking, and the students were protesting in larger and larger numbers on and off campuses around the country.

The Kopassus (Special Forces) had a special group, Team 6 or something like that, that was involved in “disappearing” student activists. That was a term that was used a lot. . . . Most of those activists who disappeared in Jakarta were later released following interrogation. Most activists in 1998, but not all, affiliated with (political party) PDI — then rebirth with new name PDIP, led by Megawati.

. . . . What struck me, I have to say, when I got to Indonesia, was finding how close the U.S. government, and our military especially, was with the Suharto regime and the Indonesian military. That had kind of been how it was for a long time. Stability was good, the economy there had been doing well, there were U.S. business interests; that was the way people approached it, and I don’t think anyone was looking for trouble or for things to fall apart.

I came in not knowing that much about Indonesia, and was really surprised by the relationship. . . . . I couldn’t understand why we were so friendly with the Indonesian military when I kept hearing about cases of human rights abuses perpetrated by the Indonesian military. . . . Maybe because of traveling and spending time with young people, but it seemed obvious that the population wanted change.

“May 12 was the spark that led to the end of the Suharto regime.”

The Fall of Suharto: By early May, student demonstrations were going on around Jakarta and around the country pretty much every day. Student protesters were calling for democracy, reform and for Suharto to step down.

May 12 was the spark that led to the end of the Suharto regime. That day, four students were shot and killed at Trisakti University following a large demonstration and stand-off with the police/military there. Two other students were also shot but survived. Others were wounded. A large number of students were trying to take the demonstration off campus and got stopped in the road. That’s where the standoff went on for several hours.

Trisakti had been known as a university for reasonably well-off kids of politicians and civil service people, not a center for student protest and activism. I had gone over to Trisakti that morning (unless it was the day before, I can’t recall exactly) and witnessed a peaceful demonstration there. They had speakers addressing the crowd and it was a big but not chaotic event. As word that students had been shot spread, anger mounted. We were hearing that it was military snipers who shot the students, but the situation was not clear.

“It felt like Jakarta was on fire.”

Riots and Chaos: It was the next day that riots got started, and instead of students protesting peacefully on campuses, crowds took to the streets. I say got started because I would hear later, as did my colleagues in POL, that the riots may have been instigated by forces in the military, that it was not purely spontaneous. And it wasn’t the students doing the rioting. It felt like Jakarta was on fire. From the embassy, we could see smoke plumes going up in different parts of the city.

As we learned later, it was the ethnic Chinese who became the primary victims of the day of rioting. Chinatown was wrecked—fires, looting, businesses destroyed. We would hear later reports that ethnic Chinese women had been raped. Terrible things happened on that day. In one shopping center being looted, many Betawi, Java, Sunda, Madura, Minang were trapped inside and died in a fire there.

“The road to home to my 2-year-old, was blocked by fires and disturbances. [T]hat was one time I was afraid, not being able to reach my child.”

Confronting the Military: I remember late morning the day of the riots (May 14) going out with a Canadian diplomat colleague, a woman, and a driver from her embassy, to see if we could get a sense of what was happening. That was scary, and we could feel the chaos in the city. We would come upon crowds, saw burning tires in streets. At one point we were on a bridge and got out of the car to see what a nearby small crowd was doing. All of the sudden, a military formation appeared on the bridge.

There was a moment of wondering, do we run and take cover? Instead we approached the military, said we were diplomats from the American and Canadian embassies, and they let us pass. I made it back to the embassy, where I stayed until about midnight. The road to home, to my 2-year-old was blocked by fires and disturbances, and that was one time I was afraid, not being able to reach my child.

. . . . That day is what triggered the evacuation. . . . [The Emergency Action Committee] met that next morning and decided the embassy would go on ordered departure, meaning the evacuation of all non-essential Americans from the embassy and consulate in Surabaya, for what I think was that night.

“There were tanks on the streets, there were blockades up everywhere. We had to go through all these checkpoints and the city was just dead.”

University Students demonstrate (November 1998) Indonesian Government | Wikipedia Commons

City on Lockdown: The situation remained tense, and I was relieved to have my family out of there. . . . When we tried to get to the embassy the next day, we found the city was in lockdown. Basically. There were tanks on the streets, there were blockades up everywhere. We had to go through all these checkpoints, and the city was just dead. I mean, there were no people out. Amien Rais had called for the people to hold a mass protest march to the presidential palace and the military was trying to prevent that from happening. Everyone was worried about what would happen if it went ahead. In the end, Rais seemed to recognize the danger and called it off.

Instead students had begun to head to the DPR, the parliament compound. They started to arrive in buses to this huge fenced-in compound that was an area not in central Jakarta. The students were permitted to enter by the hundreds. And over a couple days some thousands of students wearing their different colored university jackets converged on parliament and essentially they set up camp there. That went on for a couple days with more and more students arriving by bus.

I went over there two or three times. The few of us left in the political section would go and check in and see what was going on there. And other embassies were sending people in and I was getting calls a lot from people inside. There were times when it got very tense, when you’d hear that there were instigators coming in to try to make trouble. And there were rumors that the military was going to come and start shooting; it was a very contained area, surrounded by high metal fencing. . . . And the military was massing outside the fence; they were there with their guns but keeping on the outside.

“I went over and it was just like a big party.”

Suharto Resigns: And then it was the morning of May 21 when Suharto announced he was stepping down. That evening there was this big celebration at the DPR compound. I went over and it was just like a big party. I remember seeing groups of military guys, inside the compound now, celebrating, dancing. It was a very festive atmosphere. But Suharto immediately named B.J. Habibie, his vice president, to be the new president. The students were looking for regime change and the vice president was not what they were hoping for, so it sort of took the wind out of the sails of this great excitement. He was seen as, well, he was Suharto’s guy. But he was talking about bringing democracy, and did start to take actions in that direction pretty quickly. That was the resolution.

. . . . I don’t think things get any better for a political officer than that time in Jakarta, being able to witness history from the front lines, to see the fall of a repressive regime and the beginning of a new road to democracy that the people—and especially the students—were demanding. It was inspiring.