Nuclear Consultative Group (NCG), or “Washington Declaration”, South Korea (Can) Own Nuclear Weapon, Explained

IMHO, the most upset (I feel) about the nuclear pact between U.S. - South Korea in the middle bilateral reception Biden - Yoon Seok-yeol is, …. a lot of people are talking (high tension) from Pyongyang so U.S. hurry to send nuclear to SK to deterrence, but too few to say (bitter) fact: Beijing, less than 600 km from Seoul, may (feel) threatened by nuclear. Threatened with (how U.S.) encircling China, indirectly. Biden and his militaristic advisers are pushing an extremely dangerous policy in Korea Peninsula, also may create seismic reaction from China. Once a hawk, always a hawk.

What if China developed a “rapid, massive” nuclear weapon to respond to this nuclear pact? Tit for Tat by Beijing after Seoul - DC agreement. Washington’s increasingly heavy-handed management of its one-sided relationship with South Korea is causing it to lose the battle for the hearts and minds among the South Korean public, and of course “thumping drum”, drumbeat to war with China. Likely provoke, not deter, simultaneously North Korea and China.

Pushing nuclear confrontation on all fronts is the path of lunacy, not a fight for the "soul of a nation" - unless the bombing another city like Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The U.S. has agreed to give Seoul a greater voice in consultations on a potential American nuclear response to a North Korean attack in return for swearing off developing its own nuclear weapons. The U.S. will also deploy more strategic assets, in addition to the periodic B-2, B-52 and nuclear-capable aircraft carrier, to the Korean Peninsula. This will reassure Seoul but do nothing to manage the wider problem (I say “manage” because there is no solving it).

Establishment of a new Nuclear Consultative Group (NCG), or “Washington Declaration”, are meaningful new steps. This, too, is welcome: US can’t be compelled to use nuclear weapons, but consultation channels with allies matters. “Washington Declaration" designed to reaffirm U.S. deterrence commitments to ROK. Seoul to maintain non-nuclear status but will have a greater voice in the deliberations of U.S. weapons deployment. In the event of North Korea's nuclear attack, Biden, only 8 hours after announcing his campaign 2024, has promised to respond overwhelmingly and decisively using the full force of the Alliance, including US nuclear weapons - President Yoon Suk-yeol of South Korea said of the new Washington Declaration. Biden reiterated that US will not be stationing nuclear weapons in the region, just visits by nuclear submarines.

The problem: South Korea may just one step again like Israel, India, or Pakistan: non-UN Security Council permanent member but having a nuclear weapon itself.

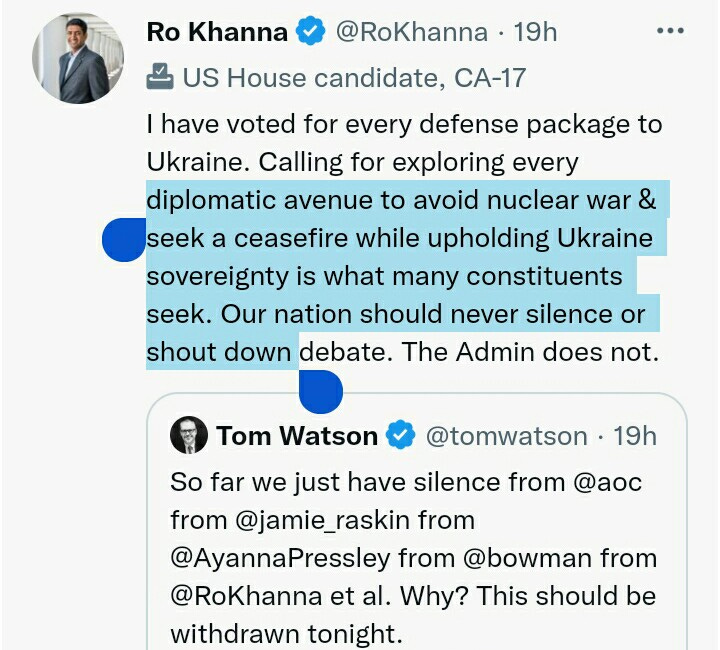

To truly prevent war, Yoon and Biden should replace the 1953 armistice with a peace agreement to officially end the Korean War — the root cause of tensions. A peace agreement would help build trust, normalize relations, and remove NK’s stated justification for nuclear weapons.

The US-ROK alliance should be built on mutual benefit, not waging war. Instead of drawing Seoul into a new Cold War with Russia, China, & North Korea, the US should de-escalate tensions, stop joint military exercises with ROK, & resume diplomacy to build peace. It’s time to end the arms race on the Korean Peninsula. The US must stop conditioning peace on North Korea’s denuclearization and instead put peace at the beginning of the process. Peace will improve the security of both Americans and Koreans.

Actually Japan, not South Korea, started the idea about nuclear weapons in the Pacific, in the wake of the Ukraine - Russia war. The late Abe Shinzo, only after Day-6 Russia - Ukraine (March 2022), announced the idea that Japan have a nuclear weapon itself, to deter China if “Ukraine-Russia typical war” really happens in the Pacific. But his capacity to speak-and-share ideas about nuclear weapons is civilian - former Japanese PM. The serious idea, unsurprisingly, came from Seoul, and even not because China but because (of course) North Korea’s Kim Jong-un.

Since 2017, according to Michael S. Schmidt, Trump “cavalierly discussed the idea of using a nuclear weapon against North Korea, saying that if he took such an action, the administration could blame someone else for it to absolve itself of responsibility.” This week, the Blue Palace team (Presidential Team of South Korea) under President Yoon stated the idea in principle that the North Korea nuclear threat should be addressed in a strict manner, there is no change to the principle that we abide by the NPT, and in order to effectively deter North Korea threats, the SK government has been focusing on strengthening South Korea - U.S. extended deterrence.

Regardless of clarification, President Yoon Suk-yeol is more enthusiastic about having nuclear weapons, rather than PM Kishida, President Tsai Ing-wen, or even President Biden himself. Yoon thinking about it in this way, especially since he was not one of the pro-nuke conservatives during the primaries, is revealing the contrary. Or because he’s very low rating (especially after the Itaewon stampede), President Yoon repeatedly tries to increase his rating to throw the North Korea issue on the spotlight.

In an Associated Press exclusive interview, Yoon explained North Korea’s spike in missile tests, growing nuclear ambitions and other provocative acts pose a “serious threat” that could lead to a dangerous miscalculation and spark a wider conflict. Rules of engagement allow for self-defense but not revenge, and knowing difference is key for international support. This is Yoon’s gambling for his (low) rating at home. If the CSIS 2026 scenario war happens, no doubt that North Korea will help China, and nuclear weapons, (if) South Korea successfully creates itself, not only owns itself, and will effectively help Taiwan and US to push back China back to mainland, not around Taiwan Straits. With Samsung, Hyundai, LG, etc, like Yoon said, it’s (actually) easy for SK to have (our) own nuclear weapons pretty quickly.

Park Chung-hee wanted nukes by 1977. Eventually, the U.S. found out about the effort and shut the thing down. Maybe U.S. facing a overwhelmed, scrambled situation in Iran, Vietnam, and Latin America in 1977 (or detail: 1970-1977, of course including Oil Embargo), so U.S. immediately say no to South Korea about nuclear weapon, because if Korean War repeated in 1977, U.S. can’t better prepare.

The U.S. State Department got wind of the scheme in November 1974, when it sent an “alert report” to then-secretary of state Henry Kissinger detailing that Park “privately told Korean newsmen last August that he had ordered Korean scientists to develop ‘atom bombs’ by 1977.” The Ford administration took the intelligence to heart and outlined general directions to the US Embassy in Seoul the following year: “our basic objective is to… inhibit to the fullest possible extent any ROK development of a nuclear explosive capability or a delivery system.”

South Korea continued experimenting in the nuclear realm post-Park. This came out during an IAEA investigation. September 2004, the International Atomic Energy Agency conducted a second round of inspections at South Korea's nuclear facilities. Former Chief IAEA, Mohamed Mostafa ElBaradei has described the tests as matters of "serious concern." South Korean officials have played down their importance, insisting that they amounted to simple research tests.

Unsurprisingly, if Seoul has a nuclear weapon and is already vigilant to use in 2025-2026, it will be significant to help Taiwan (and U.S.).

South Korea joins a small club of countries, again, like Israel, India, and Pakistan, who used the mere threat of acquiring atomic weapons to wrest concessions from the United States. Let's first illuminate ROK's bargaining strategy. The basic contours have been on vivid display over the past four months. Back on Jan 11, Pres. Yoon kicked off the gambit by publicly (AP exclusive interview, like I said) musing about South Korea acquiring its "own nuke."

But Yoon also made this not so subtle threat of proliferation conditional on the outcome of negotiations with Washington D.C. This strategy is not new. During the Cold War, for example, West Germany used investments in nuclear energy technology to put pressure on Washington for stronger security commitments. Bonn managed to wrangle a perm seat on NATO's Nuclear Planning Group. As the German case illustrates, allies can prey upon American fear of nuclear proliferation by moving, or threatening to move, closer to the bomb until Washington complies with requests for additional political, economic, or military support. Former President Lyndon B. Johnson’s reassurances to West Germany on NATO nuclear matters in the 1960s: US meeting demand signals from allies with a quid pro quo on nonpro commitments.

South Korea faces some hard constraints on mobilizing its nuclear energy program to make this threat more credible (it basically needs prior consent from Washington to enrich uranium or reprocess plutonium at commercial scale). Instead, ROK leaders appear to have made several moves at home. First, elite stakeholders have long been empowered with resources to sustain small scale work on ENR tech. This maintains the knowledge base to build larger facilities later, thereby bolstering threat credibility.

The second move involves cultivating broad public support for nuclear endeavors. This tactic lowers domestic barriers to the bomb while increasing the political costs of backing down over nuclear issues in negotiations. Add in ROK's longstanding development of conventional strike capabilities (with US encouragement) that could be converted into nuclear delivery systems, and Seoul was playing a decent hand to push for stronger security reassurances. For this gambit to work, however, Yoon would need to offset the growing concern about ROK proliferation with a stronger commitment of nuclear forbearance. And initial reporting indicates that this is precisely what ROK put on the table.

Allies & partners are increasingly likely to seek greater protection from the US. Toying with the bomb can be a useful way to shore up such security commitments. But the problem: Beijing only less 600 km from Seoul. And Sunday, April 16th, Putin met Chinese Defence Minister Li Shangfu in Moscow (just 10 days ago before Xi Jinping - Zelensky call), and both men hailed military cooperation between Russia & China. 2 Permanent Members of UN Security Council, and own nuclear weapons.

The concern I have is that leaders often find it difficult to put the nuclear genie back in the bottle. Domestic politics could distort the incentives South Korean leaders face when it comes to limiting their nuclear options over the long run. For instance, South Korean public support for the bomb was already alarmingly high before Yoon's gambit, as polling research February 2022, before Ukraine-Russia war started. April 22, 2023, Yoon’s approval rating only 27%.

Perceptions of Korean public very much not the issue. Polls repeatedly find Korean public broadly thinks US is credible. Perhaps too credible. This is reassurance of the elite. And if Trump wins GOP nomination there won't be enough declarations in the world.

Strengthening extended nuclear deterrence may have unintended consequences on this front. Highly credible US security commitments can stoke fears of entrapment among allies, leading them to consider independent nuclear arsenals. The take home is that ROK pulled off the rare feat of making its proliferation threats and nonproliferation assurances credible. This is a fine line to walk. But it remains to be seen whether the deal cut in the Washington in last December 2022 will dampen domestic drivers of proliferation in ROK.

At the summit, there's a doubling down on rhetoric about ending the North Korean regime if it were to ever use nuclear weapons. Is this credible? Would the U.S. and ROK really risk a deadly war to "end" the regime after, say, DPRK tactical nuke usage on a small West Sea island?

Biden reiterate again "Look, a nuclear attack by North Korea against the United States or its allies or partisans — partners — is unacceptable and will result in the end of whatever regime, were it to take such an action." Yoon also reiterating "Our two countries have agreed to immediate bilateral presidential consultations in the event of North Korea’s nuclear attack and promised to respond swiftly, overwhelmingly, and decisively using the full force of the alliance including the United States’ nuclear weapons."

US-ROK NCG is likely to be duplicative of existing intra-alliance consultations on US nuclear policy, but stands to elevate ROK perceptions of input into US process. Over long-run, potential for NCG or an NCG-like mechanism to be trilateralized with Japan, too, or of course (another) QUAD but specific East Asia: (with) Taiwan, very sensitive for China.

Now, while it’s great to see Yoon administration reaffirm ROK’s nonpro commitments, steps will have to be taken back home to reassure Seoul’s pro-nuclear armament strategic elites that existing cocktail of conventional deterrence + alliance extended deterrence is sufficient. ‘Washington Declaration’ may be insufficient because it doesn’t go far enough in putting ROK hands on the proverbial nuclear button.

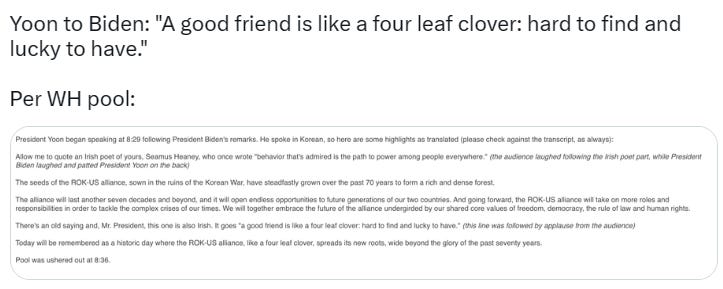

But Yoon’s visit is more than just ceremonial. The backdrop for his week in Washington is a sense of uncertainty surrounding the relationship between longtime allies, even as both Yoon and President Joe Biden stress the alliance is as strong as ever.

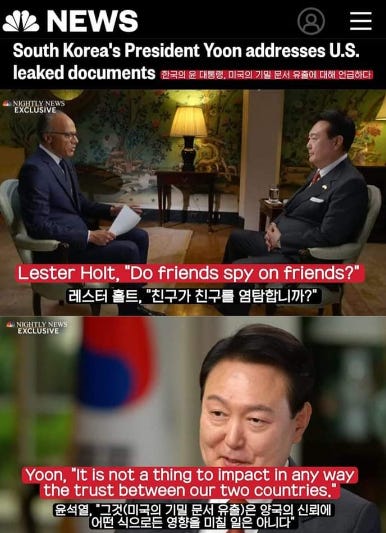

The relationship was tested by the recent Pentagon leak of classified information on the war in Ukraine, where leaked intelligence documents suggested the U.S. was spying on South Korea. Yoon dismissed those claims and his government did not air any public complaints, an approach that came at some political cost as it drew public criticism in South Korea as an act of obedience and submission towards the U.S.

“There’s increasing doubts and distrust about whether or not the U.S. is actually trustworthy to deliver on a commitment to defend South Korea from a potential nuclear attack by North Korea,” Scott Snyder, senior fellow for Korea Studies and director of the U.S.-Korea policy program at the Council on Foreign Relations, said in an interview with Nightly.

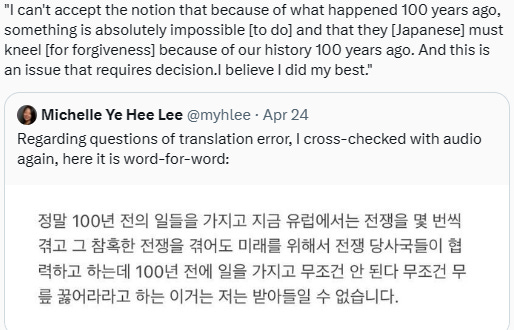

While Yoon has focused on strengthening relationships with allies abroad, back home the South Korean public has also expressed growing displeasure with his handling of domestic issues, such as inflation and record high energy prices. During his summit with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida on March 16 — a nation with which South Korea has a strained relationship due to Japan’s brutal history of colonial rule in the Korean Peninsula during the early- to mid-1900s — Yoon announced a plan that no longer demands Japanese companies compensate South Korean forced labor victims. That plan, which 60% of South Koreans oppose, generated a swift backlash. Following his summit with Kishida, Yoon’s approval rating dropped to 30 percent. April 22, 2023, Yoon’s approval rating only 27%

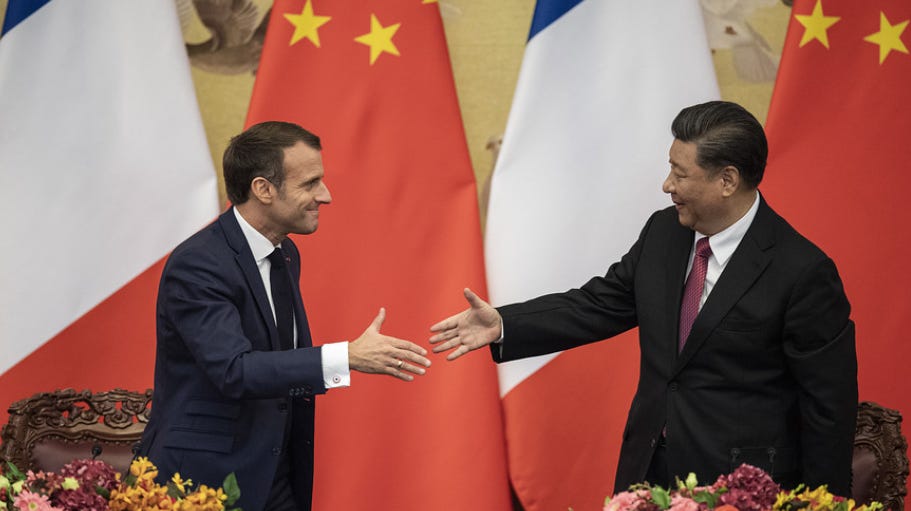

As for Biden, his Indo-Pacific strategy is largely reliant on maintaining strong relationships with both Japan and South Korea. And despite longstanding tensions, the three countries have made it clear that a trilateral partnership is a priority in the face of China’s growing economic and militaristic competitiveness, Russia’s war on Ukraine and increasing threats from North Korea.

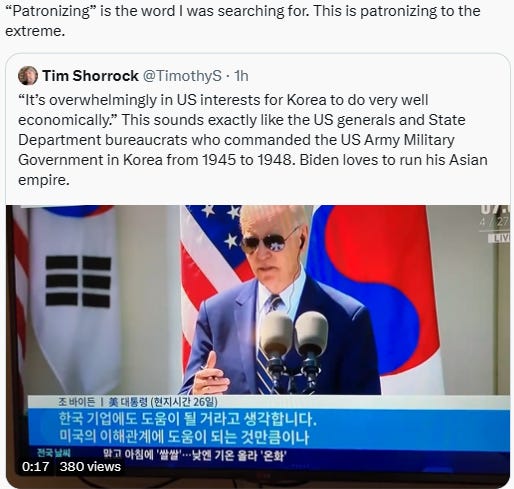

One of the Biden administration’s asks from Yoon includes a block on filling shortfalls on chips, anticipating Beijing’s possible ban on sales by U.S. company Micron, according to the Financial Times. South Korea remains one of the most China-dependent economies, with exports making up 40 percent of the country’s national income.

“South Korea has been, prior to Yoon’s alignment, identified as kind of the weak link for the U.S. because it had been so exposed to China economically despite the security alliance to the United States,” Snyder said. “And that means that there is something that South Korea has to lose.”

Biden is also asking Seoul to provide munitions to Kyiv, a move that would force Yoon to override its Foreign Trade Act that blocks the sale of weapons to countries at war and the re-export to third-party countries. South Korea has previously supported Biden’s push for Ukraine aid and provided $100 million to Ukraine last year.

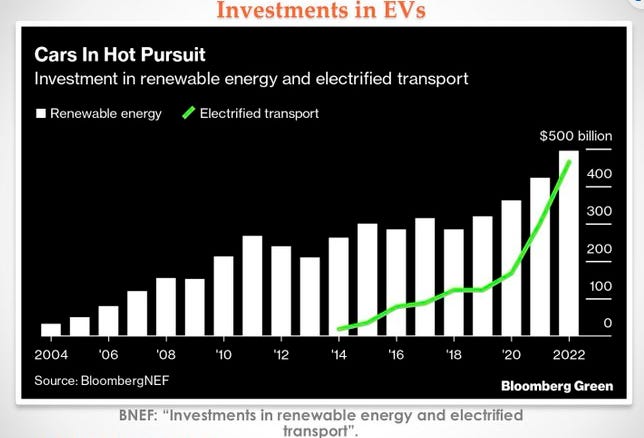

Notably, the deals will see South Korea’s presence in the U.S. electric vehicle (EV) battery market continue to grow.

But the flurry of announcements has also served to paper over major challenges in the countries’ economic ties, as Washington’s push to contain China has impacted ROK firms as well. And the resultant feelings of discontent now simmering in South Korea risk causing more problems for the alliance down the road.

During the state visit, a consortium of American high-tech firms unveiled plans to invest a combined $1.9 billion in South Korea, targeting areas such as clean hydrogen fuel, semiconductors and environment-friendly facilities. One planned joint project — small modular reactors (SMRs) — has the potential to revolutionize the energy industry and contribute to decarbonization efforts.

These investments aim to strengthen supply chain collaboration and facilitate eco-friendly energy transitions.

Further, Netflix’s pledge to invest $2.5 billion in Korean content over the next four years following a meeting between Yoon and its co-CEO Ted Sarandos will provide a significant boost to the Korean entertainment industry.

South Korean businesses have also pledged to invest in the U.S. market. In response to the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), companies like SK On and Hyundai Motor and their affiliates plan to invest $5 billion in an electric vehicle (EV) battery plant in Georgia. Additionally, Samsung SDI and General Motors are collaborating on a $3 billion battery plant in the U.S.

These substantial investments demonstrate South Korea’s dedication to the EV battery market and its strategic positioning within the U.S. supply chain.

Despite these encouraging signs, the numerous memorandums of understanding (MOUs) that South Korean and American businesses have signed recently mask Seoul’s deep-seated concerns about Washington’s intentions and fears of competitive disadvantage.

In Sept. 2022, the ROK banned L&F Company, a domestic battery materials producer, from building a new plant in the U.S. L&F planned to shift some of its production in response to the IRA, which favors electric vehicles using materials processed in the U.S.

The energy ministry cited the possibility of key technology leaks that could damage Korea’s national security when issuing the ban. The Prevention of Divulgence and Protection of Industrial Technology Act designates dozens of technologies as national core technologies, including battery-related innovations such as mid- to large-sized lithium secondary batteries for electric vehicles and high-nickel anode materials.

Even so, the South Korean government cannot simply erect its own economic barriers, as doing so will inflict long-term damage to ROK businesses as they lose out to their Chinese competitors.

The IRA only provides subsidies and tax credits for batteries that do not depend on “foreign entities of concern” for their minerals and components. The initial assumption was thus that the IRA would also force U.S. firms to cut out Chinese manufacturers in favor of South Korean companies.

However, Ford Motor Company’s decision to license lithium iron phosphate (LFP) technology from China’s Contemporary Amperex Technology Company Limited (CATL) presents a formidable threat to South Korean battery makers. Ford’s EVs will still be eligible for IRA tax breaks because CATL’s batteries are manufactured in Michigan.

The Ford-CATL agreement represents a particularly detrimental development for South Korean manufacturers, and it is largely due to Washington’s failure to narrowly define the IRA’s “foreign entities of concern” clause.

Consequently, South Korean companies may not opt to keep their production facilities within the ROK due to concerns about losing market share if they maintain their operations domestically.

Before Yoon Suk-yeol traveled to the U.S. for his summit with President Joe Biden, the White House requested that South Korea encourage its chipmakers, Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix, not to fill any market gap in China if Beijing bans U.S.-based Micron Technology from selling chips.

Beijing launched a cybersecurity review of imports from Micron, America’s largest memory chip-maker, citing its need to “ensure the integrity of its information infrastructure supply chain, prevent network security risks and maintain national security.”

The White House’s request is a sore subject, as it marks the first known instance where Washington sought an ally’s assistance in enlisting its companies to counter China. Further, South Korean businesses have already suffered significant losses partly as a result of the U.S. CHIPS and Science Act.

The U.S. bars recipients of $53 billion in CHIPS Act subsidies from engaging in “certain significant transactions” involving expanding chip manufacturing capacity in China, or “countries of concern,” for 10 years.

South Korea’s main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung implied in a statement that the U.S. is treating South Korea as if it were a vassal state, making unreasonable demands and behaving disrespectfully. “Our country does not have the authority to ask our businesses what to export or not,” Lee added.

“Our national interests, as well as the lives and livelihoods of our people, must always come before any alliance. It is essential to safeguard our semiconductors, the backbone of our economy, from discriminatory practices.”

Yoon Suk-yeol’s approval rates have fallen in the past few months, and a leading cause for that has been voters’ disapproval of his foreign policy. His approval rating dipped to 27% before slightly rebounding to 31% shortly before his departure to Washington. Yoon’s friendly approach toward Japan and the U.S. has also been described as humiliating and submissive.

The MOUs being announced this week, for all the benefits they aim to create, risk fostering resentment in the long run if alliance managers don’t deftly handle the percolating discontent about how U.S. policies have impacted South Korea.