There's No Way To Make Everyone Happy: Lockdown Is Over, WFH Ended

Some people enjoyed WFH 35 months. Concierge refuses entry to a mortally ill man, a courier, a rider, never ever in his life gets a privilege namely “WFH.” In Indonesia, courier died because fatigue.

No, not only the 1 year Ukraine - Russia war this week.

5 Days ago, February 19th, three years after Bergamo Italy watched the news coverage about a worrisome situation in China about “some virus”, then we called it “coronavirus.” Then, later weeks, Bergamo introduced the first nationwide lockdown of the pandemic, much of the world remains in the grip of what economists Jose Maria Barrero, Nicholas Bloom and Steven Davis have called “Long Social Distancing”.

It’s hard to believe we will return to 95 per cent attendance at the workplace in my lifetime. But still a lot of people, even since the pandemic began, never received privileges, namely “Work From Home”. There's always an exception to every rule.

This note-newsletter is my tribute to, at least, 25 persons-couriers I had. I care about him/her.

Most WFH aren’t software engineers or video game developers, they're accounting, HR, customer service etc and many are working in small to medium sized businesses, not fun for a small business when the secretary or other is working from home. Netflix, Twitter, Microsoft, Facebook, Google are already cut off because they are losing valuation 20-40%. A weakened labour market will embolden business leaders to be more explicit about their pro-office messaging.

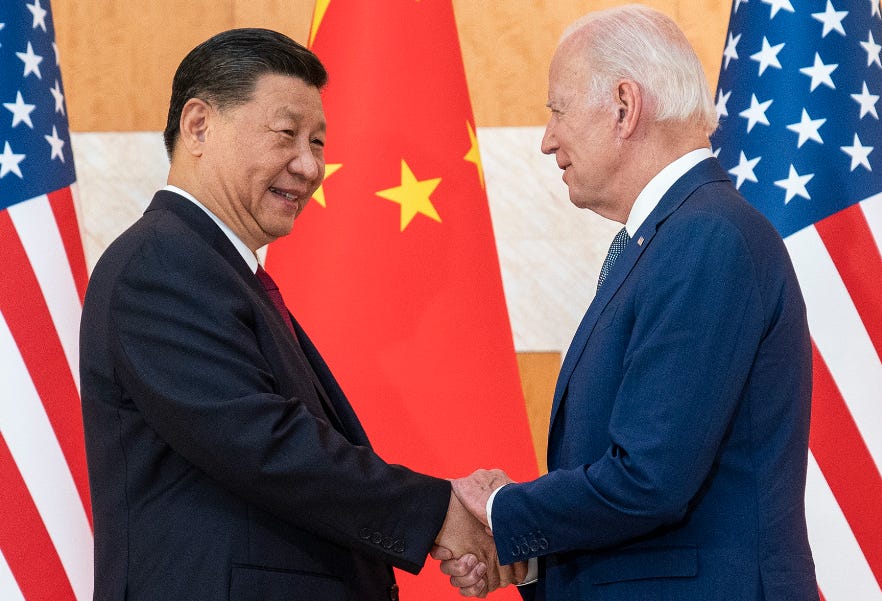

Just one awkward example. Last year some people complained their schools did not allow them to Zoom from home and asked them to go back to office to Zoom. They should take comfort that U.S. Climate Change Envoy John Kerry just flew all the way to Tianjin to Zoom with Wang Yi and Yang Jiechi instead of doing it in his basement. A good gesture, even better gesture rather than a canceled Blinken trip to Beijing over a balloon spy.

CDC researchers finally admit natural immunity is superior to protection from COVID vaccines, in a new study. The natural immunity happens if there is no more brutal lockdown, like China, or Indonesia’s PPSB - PPKM. Lockdown is over, WFH ended. In the wake brutality of PPSB, I was delivering package-birthday, alone, to someone I was care about.

It’s match night in Bergamo, Italy. The local football team, Atalanta, is playing an important game in the Coppa Italia against Lazio, a team from Rome. Atalanta's stadium sits in a neighborhood alongside the Citta Alta, the upper city, the historic part of Bergamo ringed by Venetian plaster walls from the 16th century. The floodlights twinkle, glittering in a cold January sky.

Down the hill, there is a bar in Bergamo. It has dark wood paneling and long, rectangular tables. The bar is named Hog, short for hedgehog. The menu at Hog features a cartoonish animal with playful eyes drawn on its cover.

The owner, Igor Prussiani, is a local, a true Bergamasco. He is from Longuelo, the neighborhood next to his bar. He loves Atalanta. He loves its players and its coaches. He loves its songs and chants. Mostly, though, he loves how it represents the dogged determination of his city. Nearby Milan may be the fashion capital of the world, but Bergamo is blue-collar, Igor says, and Bergamaschi know how to work, how to sweat, how to toil. On the inside collar of Atalanta's jerseys the phrase "La maglia sudata sempre" is written. Roughly translated, it means, "The shirt is always wet."

On Atalanta match nights, Hog overflows with people. It has beer taps that hang from the ceiling. It has a list of original hamburgers, including the "Hipster," which features half a pound of beef, an artisanal bun, egg, cheese, bacon, onions and barbecue sauce. It is a meal that stays with you for days. The Hipster is so adored it is normally made in batches, then delivered to the hundreds of customers crammed into the tables in the dining room. During games, the singing never stops at Hog except for when Atalanta scores and everyone shrieks in ecstasy.

Atalanta's fans watch their team beat Lazio from home. Igor watches from his restaurant. It is how it has been for months, through lockdowns and quarantines and, of course, the staggering coronavirus death toll that this city has endured. You might think the pandemic began in the Western world with Rudy Gobert and the NBA, also NFL, MLS, NHL, MLB shutting down on March 11; you might think that was the tipping point. It wasn't. It was in Bergamo, where three weeks earlier, everyone went to sleep thinking they had just experienced the best day of their lives and woke up to a nightmare.

Feb. 19, 2020, and Igor opens his bar for lunch. There is a decent rush in the afternoon, but the dining room really starts filling around dinner. Igor has had reservations on every table in the place for months. Atalanta is playing in the Champions League round of 16. For a small team whose only significant trophy came in 1963, Atalanta's game against Spanish club Valencia, a two-time finalist in the competition, is something historic.

The game itself is in Milan, about 40 miles down the road. Atalanta's stadium is tiny and built in 1928. It hasn't been modernized to Champions League standards. So Atalanta plays Valencia in the famed San Siro instead, one of soccer's grandest stages.

The city of Bergamo's entire population is only 125,000, but some 40,000 Atalanta fans make the trip. Those who don't go to watch in person pack into bars like Igor's; those who do find plenty of company on the road. Normally, it takes 45 minutes to drive to Milan; on this night, the ride from Bergamo takes up to three hours.

At this point, to repeat: This was Feb. 19, 2020. So while now we are inured to the frantic pace of coronavirus news, at that moment it was still something new, something foreign. Should there have been an inkling? Maybe. But it is only human to look away from something scary for as long as possible, to imagine, to hope, it won't come near.

On Feb. 19, 2020, the people of Bergamo see the virus as something in China, telling each other, "OK, it's 15,000 kilometers away from here and that's not our business," says Andrea Losapio, a journalist who has covered Atalanta for years. On Italian television on Feb. 19, Andrea says, the ratio of news stories about Atalanta in the Champions League to stories about the coronavirus is "at least 10 to 1."

That ratio, obviously, flips fairly quickly in the aftermath of the game, and Gori does not hesitate to say that "the week following the game was one of the strangest weeks of my life." On Feb. 20 -- the day after the match -- Gori learns of the first reported COVID-19 case in a nearby town. On Feb. 21, 14 more positives are reported in the Lombardy region, including the doctor who was treating one of those initial cases. On Feb. 23, the first two cases in Bergamo are identified.

"Then every day?" Gori says. "More and more."

At first, Bergamo mayor Giorgio Gori and other Bergamo officials are unfazed. They continue with discussions about the outdoor watch party for the next Atalanta game. Bergamo mayor Giorgio Gori had no idea a public health crisis was about to hit his city when he attended Atalanta's Champions League game with his son. He even started making plans for a public viewing of the return leg in the city's main square.

Then on March 5, Gori checks his email at 11 p.m. and sees a note from a regional public health official whom he does not know: "Mayor I have to explain what's really happening -- you have to realize what's really going on."

Late at night, nearly ready for bed, Gori feels chills as he reads in this email about exponential spread and a possible shortage of PPE and the potential for hospitals to be crippled by overwhelming demand. Within weeks, it all happens, just as predicted. Rising positives. Resource issues. Overflowing hospitals.

By March 24 -- about a month after the game -- nearly 7,000 people in Bergamo have tested positive and more than 1,000 are dead. On March 27, The New York Times publishes a story detailing Bergamo's devastation as, essentially, the first city outside of Asia to be completely enveloped by COVID-19. The headline quotes a local funeral director: "We Take the Dead from Morning Till Night." One local newspaper is overwhelmed by death notices. As COVID-19 ravaged Bergamo, questions arose about the role Atalanta's game played in spreading the virus. And spread throughout Europe. And the world.

The significance of the Atalanta-Valencia Champions League game in spreading the coronavirus in Bergamo quickly becomes a divisive point. Fabio, the fan who grew up just a few hundred yards from the stadium, says that early on, some "people from Italy look at us like bad people, like the people that go around and spread the virus." A pulmonologist in Bergamo is quoted in the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera describing the Atalanta-Valencia game -- with 40,000 people together in the stands -- as "a biological bomb."

Amidst all the fear and loss, that sort of description gains traction. Some see the match as a symbol for what has gone wrong in Bergamo, if not its primary symptom. The Associated Press publishes an article labeling the Atalanta-Valencia match as "Game Zero." More than a third of Valencia's team and staff turn up with positive tests after returning home, and the second leg is played at an empty stadium.

The science is complicated, and not entirely definitive. According to Dr. Seema Lakdawala, an expert who studies the transmission of viruses at the University of Pittsburgh, there are complex analyses still to be done on aerosol dispersion patterns in an outdoor environment. Fans jumping all over each other at the San Siro, she says, poses a risk of transmission, but in her opinion, on a game night, restaurants and bars like Igor's would be even "more of the disaster scenario," because "every time you talk, breathe [and] shout, you're expelling viruses and aerosols ... [which] are going to stay in the air for longer, especially in poorly ventilated spaces."

Buses and trains and subways that Atalanta fans took -- again, indoor, contained spaces -- were likely environments rich for spreading the virus as well. While the match itself might well have been an "accelerant" in Bergamo's deterioration, it was "not the only mass event that could have influenced the situation."

What is certain is the spread. Twenty percent of the people from Bergamo who attend the match in the San Siro ultimately show symptoms of COVID-19 within a few weeks, according to one study. That includes Fabio. His fever is high but, fortunately, his symptoms do not become dire. As he recovers in isolation, he follows the anguish on his phone.

Every morning, he says, he wakes up and checks a group text with friends from Bergamo. And every morning for 16 straight days, he says, "I was obliged to make condolences to someone" for the death of a parent or in-law or uncle or aunt.

Even amidst an unprecedented crisis, Bergamaschi Mayor Giorgori Gori says, Bergamaschi are always able to fall back on the thing they know best. They organize. They volunteer by the thousands. They distribute masks. They deliver groceries and medicines to seniors. They build, within weeks, a makeshift hospital in Bergamo's fairgrounds to help ease the overload.

They work. Through lockdowns and quarantines, through school closings and business restrictions, through spikes and valleys in infection rates, they work. They work to hold their city together.

Igor watches, too, and talks with other restaurant owners about when, finally, the COVID-19 vaccine will be so widespread that he might open Hog's doors again. He has lost nearly 700,000 euros during this crisis, but his faith in Bergamo has never wavered. As the restrictions lift, he says, he is thinking of opening a second location. "It would be nice to have a full bar and eat a lot of Hipster burgers," he says.

One thing you don't hear very often from Bergamaschi is a desire to "get back to normal." There is no such thing. Not here. Not in a place that has lost so much. Nearly 28,000 have died in Lombardy, the region that contains Bergamo. Too much has happened to this city, to these people, for there to be a return -- a resumption -- of anything.

Get back to normal. Afterwards, for some people, who survive under covid, too enjoyed working from home, say goodbye to work from the office. Survey in January 2023, A majority of London’s workers, 3-in-4 Londoners, would rather quit their jobs than return to the office full-time, and many are demanding inflation-busting pay hikes to give up their right to flexible working.

June 2022, Elon Musk’s Ultimatum to Tesla Execs, Return to the Office or Get Out. (Was) World’s richest man demands at least 40 hours a week in office. September 2022, General Motors walked back plans to require employees to return to a company office several days a week, delaying a change to its remote-work policies until next year, according to an internal memo. Nearly 2 years ago, August 2021, reports most Americans would take a pay cut to WFH.

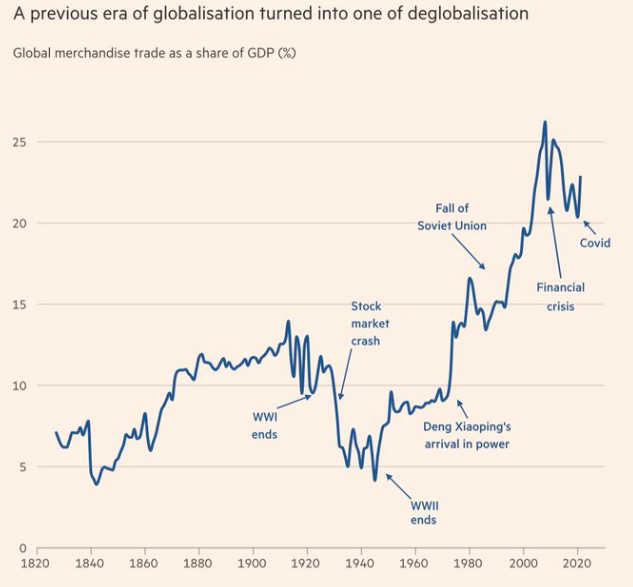

Although the acute phase of the pandemic has passed in the western world, working patterns have not returned to normal. Barrero et al have been running a survey of working-age Americans since May of 2020, targeting those with a history of paid work.

They find that before the pandemic, less than 5 per cent of working days were spent working from home — the result of a long slow climb from less than 0.5 per cent in the 1960s through 1 per cent in the early 1990s. In the first wave of the pandemic, that figure jumped to more than 60 per cent before quickly ebbing.

But again, not everyone gets a privilege, namely “WFH.” Rider, Courier, must be in the field, on the road. 2 Weeks ago, an Indonesian rider / courier of some start-ups, died in front of the home of a receiver package, because very hectic-fatigue.

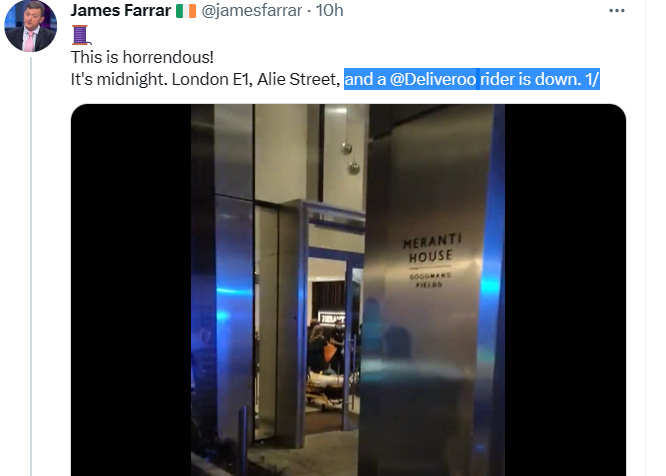

18 Hours ago, Mohamed, a rider / courier from Deliveroo, abruptly fell ill in front of Meranti House, an apartment in London (London E1, Alie Street). Mohamed was making a delivery at the front door of the swish Meranti House when he collapsed at about 1030pm.

He never made it inside the concierge controlled lobby. Some people at the Boom Battle Bar came to his aid and were calling an ambulance. People who were watching Mohammed abruptly fall, asked Meranti House security if we could move Mohamed off the cold ground outside and onto the sofa inside. They said no although much later they relented.

Mohammed seemed over heated so we took down his hood. Then he became cold and the bar brought out a foil recovery blanket. It was absurd that he could not be brought inside the Meranti so the people near Meranti House (who were watching Mohammed abruptly fall) asked again and they agreed he could enter. All the while the Deliveroo app kept alerting Mohammed to complete the delivery. Although his gps records would indicate there is a problem,nobody from Deliveroo management called to check if Mohammed was ok. This (app) kept alerting nearly the same case in every country with very dominant start-ups in big cities, including Indonesia. Mohammed’s wife was desperately worried. An ambulance eventually arrived to treat Mohammed more than an hour after the first call.

What have we come to with this gig economy across the world?

1. A building concierge refuses entry to a mortally ill man collapsed outside (this case not only in London, but in Indonesia)

2. An employer incessantly pings to demand delivery but fails to make a welfare call

3. A consumer steps over the mortally ill to get to their purchases

Imagine: some people enjoyed WFH for 35 months. Some people must work outdoors, even get refused. Concierge refuses entry to a mortally ill man, a courier, a rider, never ever in his life gets a privilege namely “WFH.”

It pays to be smart, or so the saying goes. A lot of startups have made major progress on unit economics (UE). Likely involves enduring pain. You will be tempted to get back to higher growth, and reduce focus on UE. Don’t get satisfied with improvement relative to your past, benchmark to best in class, don’t stop at 70% of the way. But the biggest earners may not be the workers who are the brainiest, according to one recent Swedish study.

The research, published in the European Sociological Review in January, found that higher general intelligence was correlated to higher wages — but only up to a threshold of about 600,000 Swedish krona ($57,300) a year. Beyond that point, the study found that ability plateaus as wages continue to rise. And earners in the top 1% score slightly worse than those in the income tier directly below them.

“We find no evidence that those with top jobs that pay extraordinary wages are more deserving than those who earn only half those wages,” wrote the authors of the study, which was led by Marc Keuschnigg, a senior associate professor for analytical sociology at Linkoping University in Sweden.

“Extreme occupational success is more likely driven by family resources or luck than by ability,” the authors added.

Still, Keuschnigg sees the lack of a correlation between intelligence and salary at high levels as a warning sign about growing income inequality between the most wealthy and the rest of society. Given that Sweden has a relatively narrow income gap, “we can speculate that we might see this even more in places like Singapore or the U.S.,” he said.

“The decisions that top earners make are consequential for a lot of people,” he added. “So we as a society might want to have the right people in these top positions.”

Much of the world remains in the grip of what economists have called ‘Long Social Distancing’ But what is striking is that the number has plateaued at levels that would have seemed unimaginable before the pandemic. In January 2021, more than 35 per cent of paid working days were from home.

By January 2022 — after a spectacular vaccine rollout and the infection of a large proportion of the US population — 33 per cent of days were still worked from home. That number stayed around 30 per cent throughout last year before dipping to 27 per cent in the survey for January. Maybe that recent dip is statistical noise; maybe it reflects new habits and policies for a new year. Either way, even 27 per cent is a radical shift from the 5 per cent of 2019. And working from home is particularly prevalent in the largest US cities — which may explain Amanda Aronczyk’s inability to give away a dozen doughnuts in midtown Manhattan. Data from the UK’s Office for National Statistics, while not directly comparable, suggests a similar picture: between 30 and 40 per cent of workers say they’ve worked from home “in the past seven days”, and there is little sign of that number falling. It is hard to believe that we will return to 95 per cent attendance at the workplace.

It’s no surprise that Elon Musk (after bought Twitter Inc.) is ordering Twitter staff back to the office within a month of taking the keys to the social media company. Workers at Tesla are fully familiar with their billionaire boss’ strict preference for being present since June 2022.

A disembodied Elon Musk looms out of darkness via videolink to laugh off Twitter crumbled chaos and explain why tunnels rather than flying cars will beat congestion.

Elon Musk may be the world's richest man but when he appeared by videolink before a business conference in Indonesia he admitted he was sitting in the dark, lit by candles after suffering a power cut.

'Really, we just we had a power outage three minutes before this,' he said, as his disembodied faced loomed above the B20 audience in Bali.

'That's why I'm like bizarrely in the dark.'

Organizers said he canceled his trip to the island at the last minute because of a scheduling clash.

Instead he used a videolink to discuss his Twitter travails, Tesla and why tunnels are a better solution to congestion than flying cars.

He was asked how it felt to have become a media mogul, and made reference to the furious response to his performance as Twitter owner so far.

'It's a little uncomfortable,' he admitted.

'Twitter is sort of media but it's not exactly media. It is a medium as opposed to media.

'But I mean, there's no way to make everyone happy, that's for sure.'

Elon Musk has been subjected to an avalanche of criticism since completing the $44 billion takeover of the Social media platform.

He fired much of its full-time workforce by email soon after the deal was completed, and then got rid of thousands of contractors, hollowing out teams that battle misinformation.

He also rolled out an $8 subscription service for the platform's blue checkmarks but had to suspend it after a slew of imposters appeared - including some posing as him or his products.

On Monday, November 14th, 2022, he addressed delegates to the B20 summit (sideline meeting, specific for businessman/woman, in G20 Summit), which aims to bring together business leaders and world leaders ahead of the Group of 20 meeting the begins on the tropical island Bali, Indonesia on Tuesday (Nov 15th, 2022).

He wore a batik shirt sent by organizers.

Musk said he would have liked to have attended the conference in person.

'I mean, that sounds fantastic,' he said. 'But, you know, my workload has recently increased quite a lot.

'I have too much work on my plate.” Elon added.

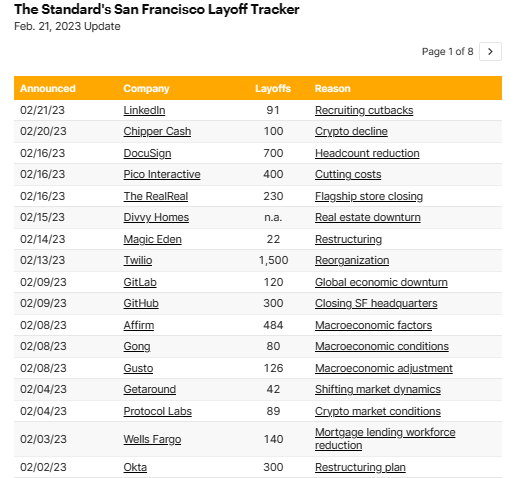

(Tracker laid off, click here)

Thanks to (stubborn) Elon forcing employees back to the office (both in Tesla and Twitter). Elon Musk, alongside Trump, play leading roles in recent San Francisco Office market distress. Columbia Property Trust’s building portfolio has another major anchor weighing it down: Twitter, which allegedly began skipping out on rent payments after Elon Musk took over the company last year.

Despite all its challenges, San Francisco remains a national leader in worker pay. After announcing a 6% increase for 2023, SF’s new $18.07 wage will rank it second among the nation’s largest 25 cities when it takes effect on July 1.

With a pay rate of $18.69 per hour, only Seattle guarantees its workers more than SF.

Many top U.S. cities still match their pay to the $7.25 minimum wage required by the federal government, an hourly rate that has not been increased since 2009. All of the big metros in Texas as well as Charlotte, Nashville and Philadelphia fall into this category of minimum minimum-wage cities.

Twitter is one of the biggest tenants across the seven properties in the portfolio, leasing space at 650 California St. and 245-249 W. 17th St. in New York. Columbia has already filed suit against the social media company for failing to pay rent.

The mortgage issues faced by Columbia are part of a larger shift within the commercial real estate industry due to remote work, meaning lower demand for leases and hollowed-out office buildings. That puts landlords in a tenuous financial position with declining cash flow as their loans come due.

Bloomberg, which first reported on the default, noted that Columbia’s mortgage has “floating-rate debt,” meaning interest rates that are variable. As federal interest rates have risen in an effort to tamp down inflation, these loans become much more expensive to maintain.

That puts the Tesla-Twitter-SpaceX boss in line with investment banks on the issue. Finance execs have generally made clear their expectation that office-based working is the norm and hybrid arrangements the exception.

In industries that rely on intellectual capital, that stance does make sense. Nearly three years since the emergence of COVID-19, the reasoning should be well understood. In the know-how profession, being in the same space gets the job done better: Casual enquiries are easier, information flows faster, serendipitous encounters spark opportunities.

Co-location retains institutional knowledge. Cultural cohesion just happens, whereas remote-only firms must resort to off-sites to replicate the effect.

Amazon employees are petitioning CEO Andy Jassy to cancel his return-to-office mandate and calling out his about-face on remote work. In a petition to Jassy sent late Tuesday (Feb 21, 2023), Amazon workers decried that their trust in the company’s leaders had been “shattered.”

After Jassy told workers in a memo last Friday that workers would be expected to return to the office for at least three days a week beginning May 1, employees began to mobilize in an effort to get him to change his mind. Since October 2021, Amazon had allowed managers to determine how often employees needed to be in the office. According to CNBC, frustrated employees are currently drafting a petition to Jassy and other members of the Amazon executive team asking for remote work and flexibility to be protected, underscoring that the RTO policy would impact the lives of employees who had planned on location flexibility.

In the memo, Jassy said that Amazon’s executive team had changed its mind over what it thought was “optimal” over the course of the pandemic. Being in the office allowed workers to “absorb” Amazon’s culture and collaborate in easier and more effective ways, the CEO stated. It also enabled people to learn from each other and fomented greater team connections, he said.

“It’s not simple to bring many thousands of employees back to our offices around the world, so we’re going to give the teams that need to do that work some time to develop a plan. We know that it won’t be perfect at first, but the office experience will steadily improve over the coming months (and years) as our real estate and facilities teams smooth out the wrinkles,” Jassy said.

Not everyone will be required to be in the office three days a week, he pointed out, but the exceptions will be limited. Overall, Amazon didn’t provide many details about how its return-to-office would work, and told employees it would be finalizing plans in the coming weeks.

Amazon was laid off more than 10,000 months ago, because of a crumbling down of valuation.

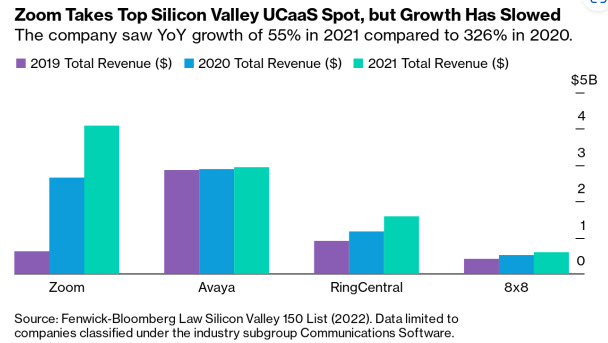

Zoom Video Communications Inc. ZM 1.61% is laying off 1,300 employees, or 15% of its staff, becoming the latest technology company to trim its workforce as it adjusts to more normalized trends after a pandemic-fueled growth spurt.

Chief Executive Eric Yuan said Tuesday he was also reducing his salary and forgoing his bonus, joining other corporate leaders across finance and tech to take pay cuts this year. He made just over $300,000 in salary for the fiscal year ended Jan. 31, 2022, and about $13,000 as part of a non-equity bonus plan. Hong Kong Tycoon Li Ka-shing Cut Zoom Stake as Shares Tumbled.

Li’s holding in the software company now represents only about 5% of his fortune, down from one-third at the stock’s peak.

Shares of the San Jose, California-based company closed at $84.66, a nearly 10% gain in Tuesday (Feb 21, 2023) trading. Over the past 12 months, the stock has fallen more than 40%. As of Jan. 31, 2022, the company had nearly 6,800 employees, up from about 2,500 employees at the same time in 2020, according to regulatory filings.

“We didn’t take as much time as we should have to thoroughly analyze our teams or assess if we were growing sustainably, toward the highest priorities,” Mr. Yuan said in a message to employees. “I am accountable for these mistakes.”

Mr. Yuan said he is reducing his salary for the coming fiscal year by 98% and forgoing his fiscal 2023 corporate bonus. Members of his executive leadership team will also forfeit their bonuses and reduce their base salaries by 20% for the coming fiscal year.

The company is slated to report its fiscal fourth quarter results on Feb. 27 (3 days from now). After surging to a high million users, Zoom has since lost over a million users because of ease restriction covid and back to office, meet - up physically to coworker again.

Zoom joins a wave of technology companies, including Dell Technologies Inc., International Business Machines Corp. and others, that have moved to trim their staffs amid rising interest rates and a leveling off of pandemic-related growth. Business-software companies have also said customers are paring back spending as they look to reel in costs.

Various companies have laid off thousands of employees in a round that was led by large technology companies, including Microsoft Corp. and Amazon.com Inc. Large companies from other sectors have made similar moves, with FedEx Corp., 3M Co. and Dow Inc. all announcing layoffs in recent weeks.

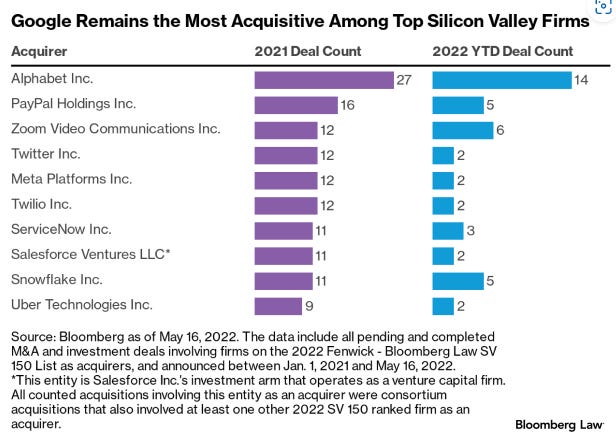

The growth of cybersecurity companies, M&A and investment activity among top firms and newcomers to the list. Although Zoom has become the top-ranked communications software company on the Fenwick–Bloomberg Law SV 150 List, its meteoric ascent stalled, and has slowed as workers returned to the (hybrid) office. Fenwick–Bloomberg Law SV 150 List data showing increased annual growth among cybersecurity providers reflects a cross-sector focus on safeguarding corporate IT systems from serious threats.

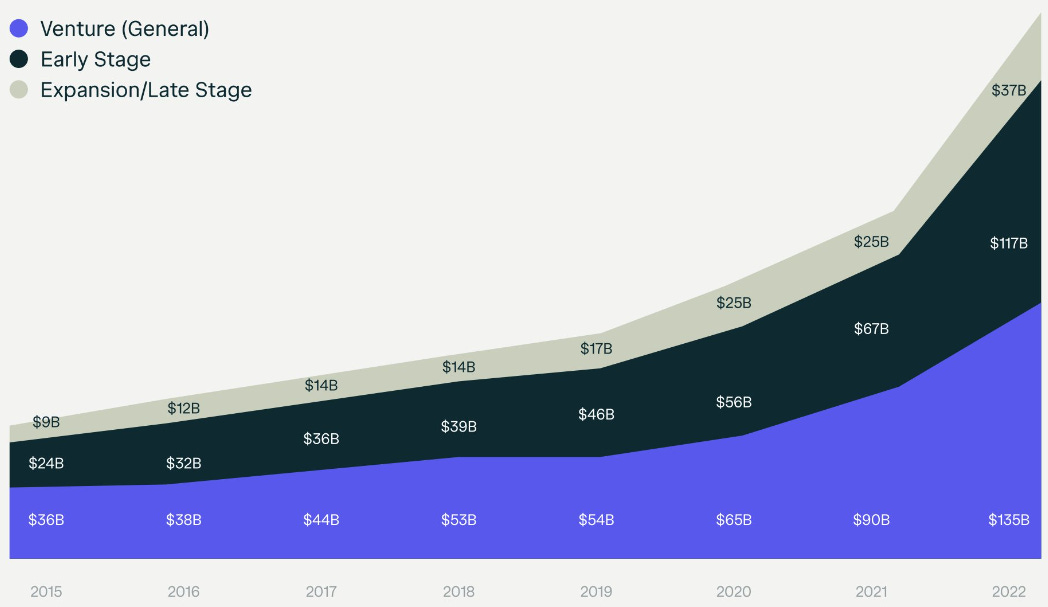

Last year, overall M&A and investment activity involving Fenwick–Bloomberg Law SV 150 firms climbed even higher than in the pandemic-defying, record-setting year of 2020. 2021 marked the fourth consecutive year that Google has been the most active acquirer and investor of all firms on the Fenwick–Bloomberg Law SV 150 List. Zoom in 3rd. Alphabet Google remain top.

17 companies made the 2022 Fenwick-Bloomberg Law SV 150 list for the first time. 66% of the newcomers' total deal activity since their formation were investments, and in 84% of those transactions, the newcomers were on the receiving end of the funding

Is brute force the best way to get people back? As the pandemic abated in the US and Europe, the banking industry went from using workplace perks as carrots to a more coercive read-between-the-lines approach based on bosses’ pro-office messaging.

A weaker labour market will embolden leaders to be more explicit about their preferred solution to the equation. The last few weeks have seen thousands of job losses announced in tech; the omens for finance are bad too. But in any industry that relies on talent, employers should not overestimate their bargaining power.

Some workers, most obviously those with family care responsibilities, need flexibility of either location or hours, or both. You can’t negotiate with need: They will take their skills elsewhere. Bosses risk narrowing candidate pools.

Combine this with a weakening economy and pressure from Wall Street leaders for office working, and it helps normalise the use of force rather than nudging to get people back to HQ.

Any advocacy for the primacy of office working in the tech sector is significant. Remote working is enabled by technology, so the industry as a whole has a vested interest in promoting it – just as real estate developers want their own staff in offices singing the merits of shiny glass buildings.

The Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes shows hybrid working is popular across all demographics. And tech workers appear particularly accustomed to remote work. The pandemic even led to tech startups in San Francisco seeing staff decamp to other cities.

It’s been hard enough for tech employers to formalise attending the office on a majority of days – Apple delayed such a policy earlier this year – let alone full-scale office-hood.

And that’s seemingly what Musk wants. He expects workers to spend at least 40 hours a week on site, subject to case-by-case exceptions.

Many people could – and do – cram that into fewer than five days. But the ordinary observer will translate the edict as: Don’t work from home, live in the office. (Quite how Musk himself would spend 120 hours a week in the offices of his three main ventures in another matter.)

Why is that, and what might the implications be? Some people still fear infection, but for most, the change reflects a lasting shift in how we view remote and hybrid working. That shift has several elements behind it.

Recommended Global Economy Office workers embrace hybrid working as post-pandemic norm The first is that we’ve learnt that working from home works better than we had expected. In a now-famous 2015 study, Bloom and colleagues had found that workers at a Chinese travel agency were substantially more productive after being randomly assigned to work remotely.

At the time, few people seemed to believe that this conclusion would carry over to most office work. They were wrong. Having been forced by the pandemic to give remote working a try, many people have discovered it works perfectly well. The second element is investment: we’ve stumped up for new webcams and comfortable office chairs at home, and replaced patchy WiFi with wired broadband connections.

We’ve also taught ourselves to use Zoom and Teams, Dropbox and Google Docs. Attending a video conference or giving a virtual presentation once seemed a Herculean task with inadequate equipment. Now it feels barely more complex than writing an email. And the third pillar supporting this permanent shift is that it’s a shift we’ve made together. That changes the social dynamic, by destigmatising those who choose to work some or all of their days from home. It reduces the benefits of commuting: why would someone even bother going to a Manhattan office if everyone else is dialling in from Brooklyn, upstate New York or even Mexico?

These events would rarely be streamed in the past. It would have seemed strange to do so. Now it seems strange not to. Some implications of all this have been well-explored: the property market will have to adjust, perhaps with more apartments and less office space in previously prime locations; restaurants, shops and gyms in smaller towns are likely to enjoy the benefits of providing to residents working remotely in distant cities; managers will have to figure out how to manage at a distance, and how to navigate the complexities of hybrid working arrangements. Yet there is another lesson to be learnt — a lesson about our own inertia.

Most of the people working from home are no longer doing so out of caution or social responsibility. They’re doing it because they like it. They could have been working from home back in 2019, but most of them weren’t. It raises the question: what other personal and cultural habits have we acquired that we should be rethinking? It shouldn’t take a global pandemic for us to find better ways to live our lives.