Reno Nevada 7.48am / Beijing 10.48pm / DC 10.48am / 8.18pm New Delhi

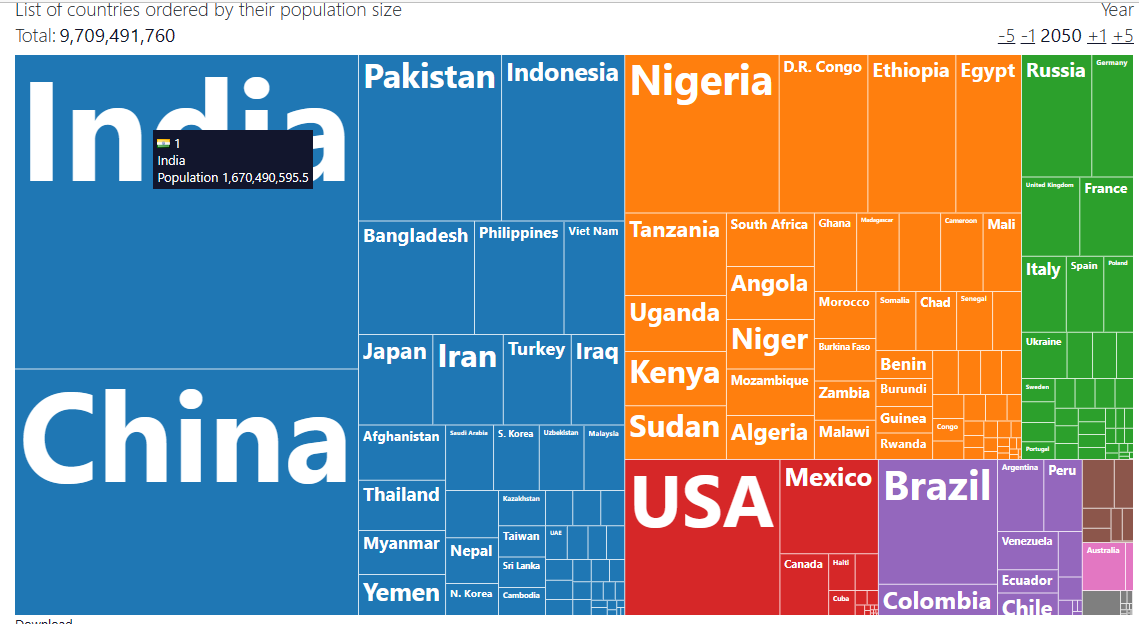

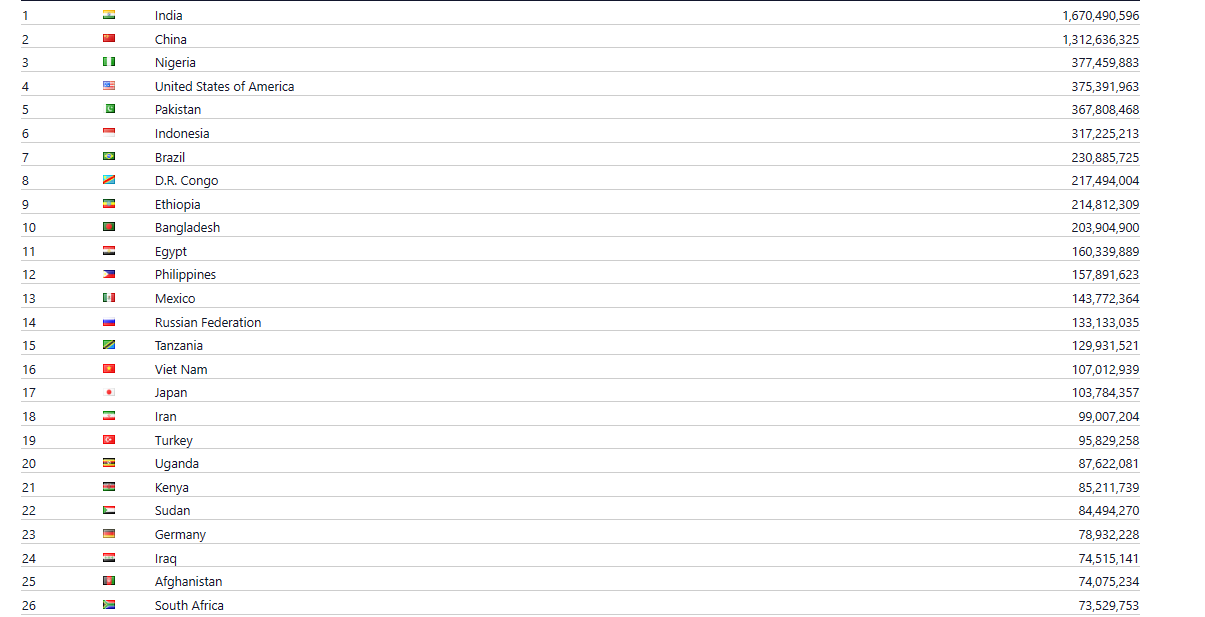

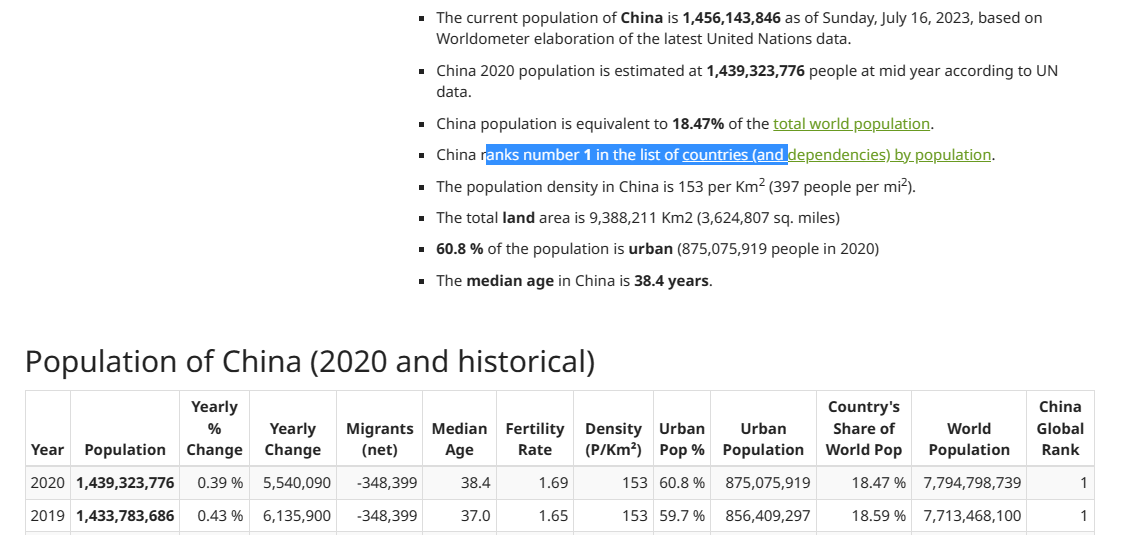

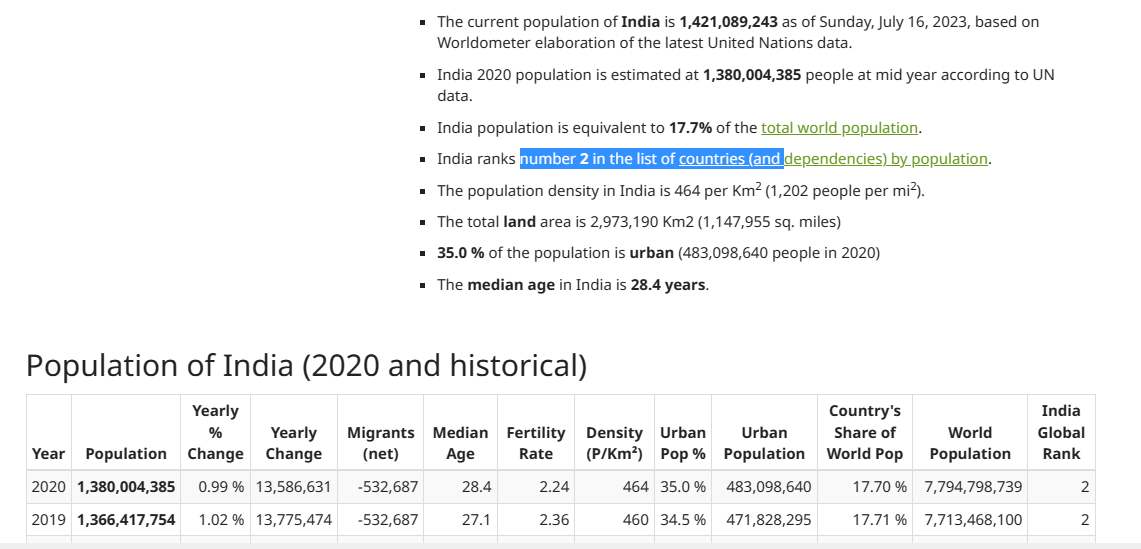

The world’s demographics have already been transformed. Europe is shrinking. China is shrinking, with India, a much younger country, overtaking it this year as the world’s most populous nation. Still debatable India already surpassed China or not. The current population of India is 1,421,052,203 as of Saturday, July 15, 2023, based on Worldometer elaboration of the latest United Nations data, and China is 1,456,143,846 —- China still bigger.

But what we’ve seen so far is just the beginning.

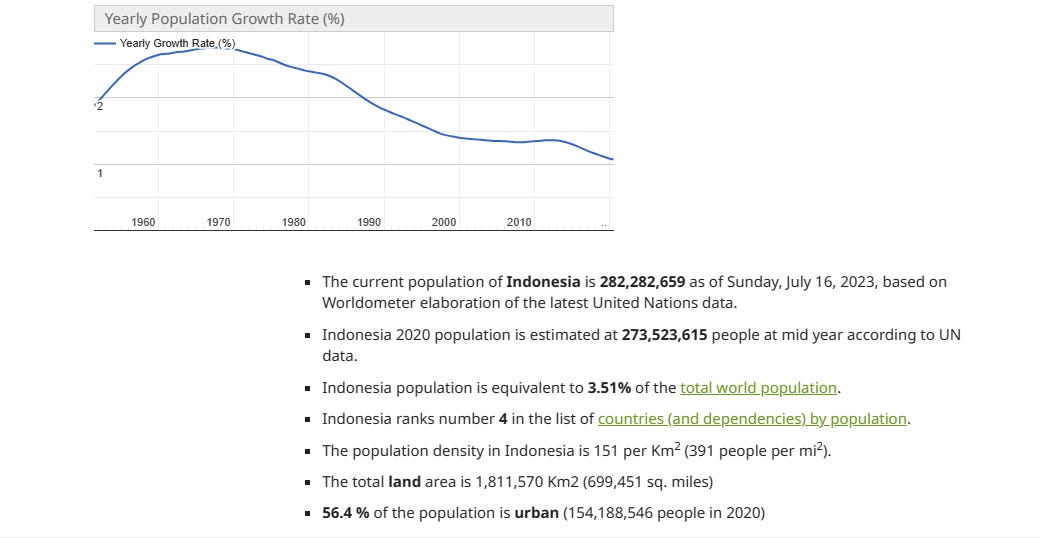

According to (same) Worldometer, Indonesia already has 282,282,659 as of Sunday, July 16, 2023 —- actually bigger than estimation by Indonesia election and Statistic Board Agency (around 275 million). But in 2050, estimate 317.2 million population, Indonesia dropped from 4th most populous to be just 6th, and countries with bigger population than Indonesia beside India and China are (estimated) Nigeria (3rd), U.S. (4th, currently 3rd but in 2050 maybe dropped to be 4th), Pakistan (5th).

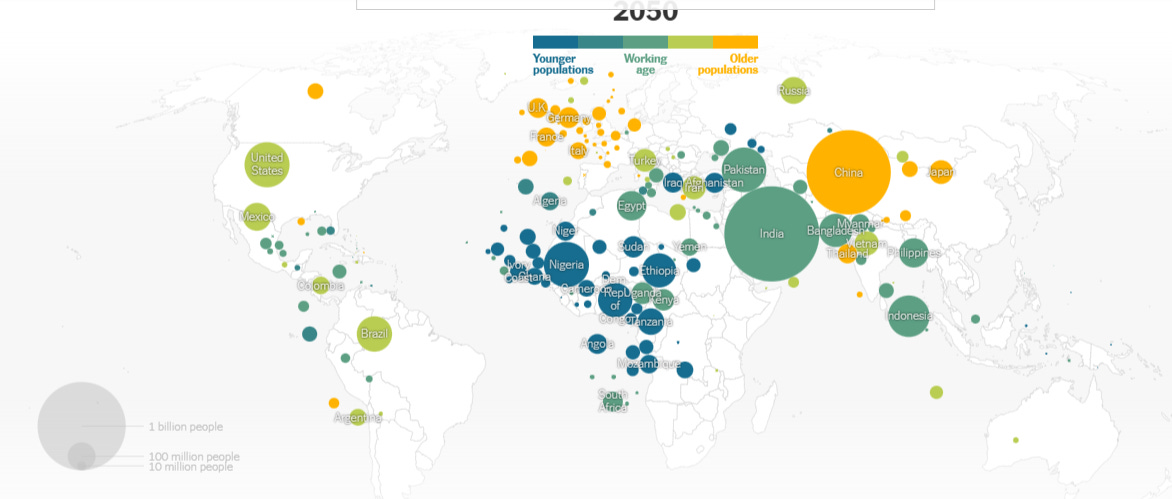

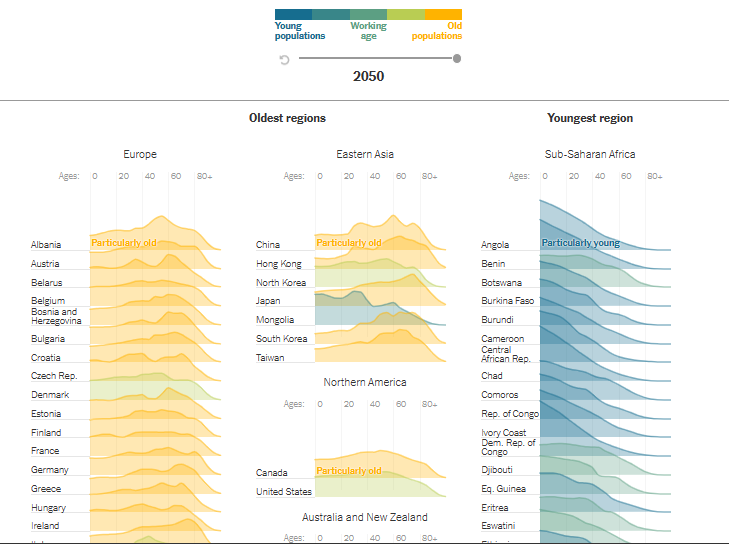

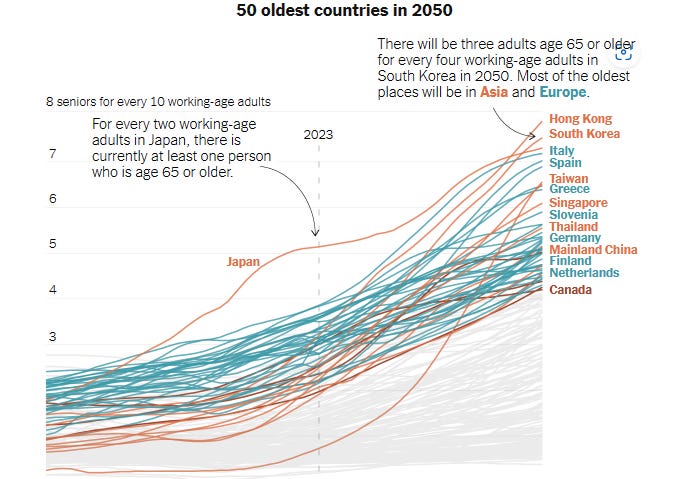

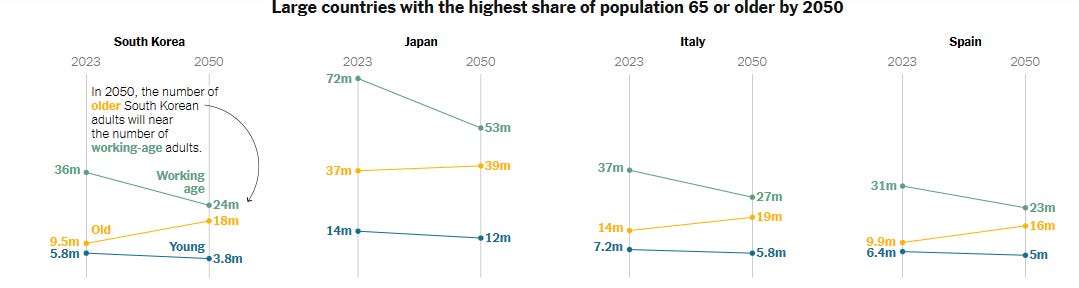

The projections are reliable, and stark: By 2050, people age 65 and older will make up nearly 40 percent of the population in some parts of East Asia and Europe. That’s almost twice the share of older adults in Florida, America’s retirement capital. Extraordinary numbers of retirees will be dependent on a shrinking number of working-age people to support them.

In all of recorded history, no country has ever been as old as these nations are expected to get.

As a result, experts predict, things many wealthier countries take for granted — like pensions, retirement ages and strict immigration policies — will need overhauls to be sustainable. And today’s wealthier countries will almost inevitably make up a smaller share of global G.D.P., economists say.

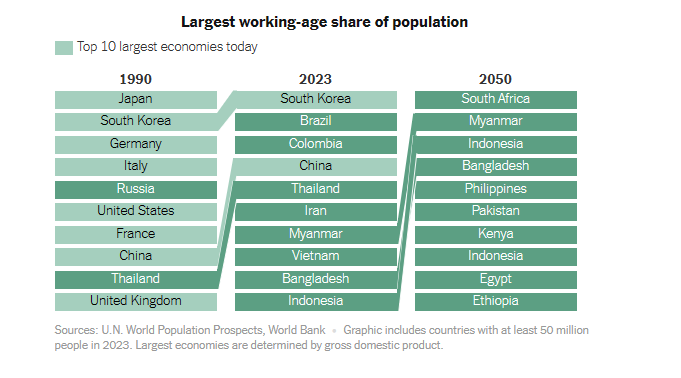

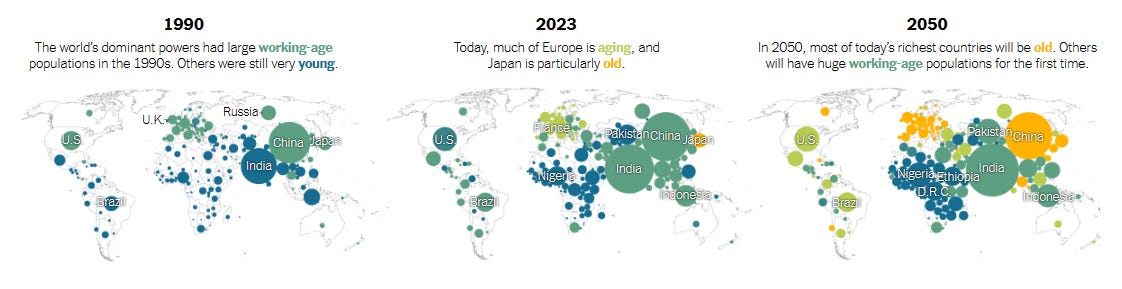

This is a sea change for Europe, the United States, China and other top economies, which have had some of the most working-age people in the world, adjusted for their populations. Their large work forces have helped to drive their economic growth.

Those countries are already aging off the list. Soon, the best-balanced work forces will mostly be in South and Southeast Asia, Africa and the Middle East, according to U.N. projections. The shift could reshape economic growth and geopolitical power balances, experts say.

In many respects, the aging of the world is a triumph of development. People are living longer, healthier lives and having fewer children as they get richer.

The opportunity for many poorer countries is enormous. When birth rates fall, countries can reap a “demographic dividend,” when a growing share of workers and few dependents fuel economic growth. Adults with smaller families have more free time for education and investing in their children. More women tend to enter the work force, compounding the economic boost.

Demography isn’t destiny, and the dividend isn’t automatic. Without jobs, having a lot of working-age people can drive instability rather than growth. And even as they age, rich countries will enjoy economic advantages and a high standard of living for a long time.

But the economic logic of age is hard to escape.

“All of these changes should never surprise anyone. But they do,” said Mikko Myrskylä, director of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research. “And that’s not because we didn't know. It’s because politically it’s so difficult to react.”

The Opportunity of Youth

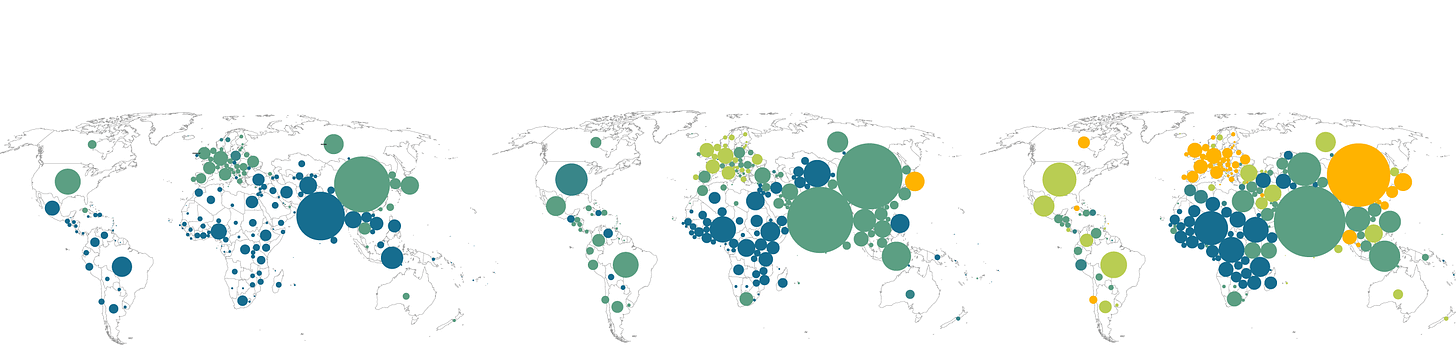

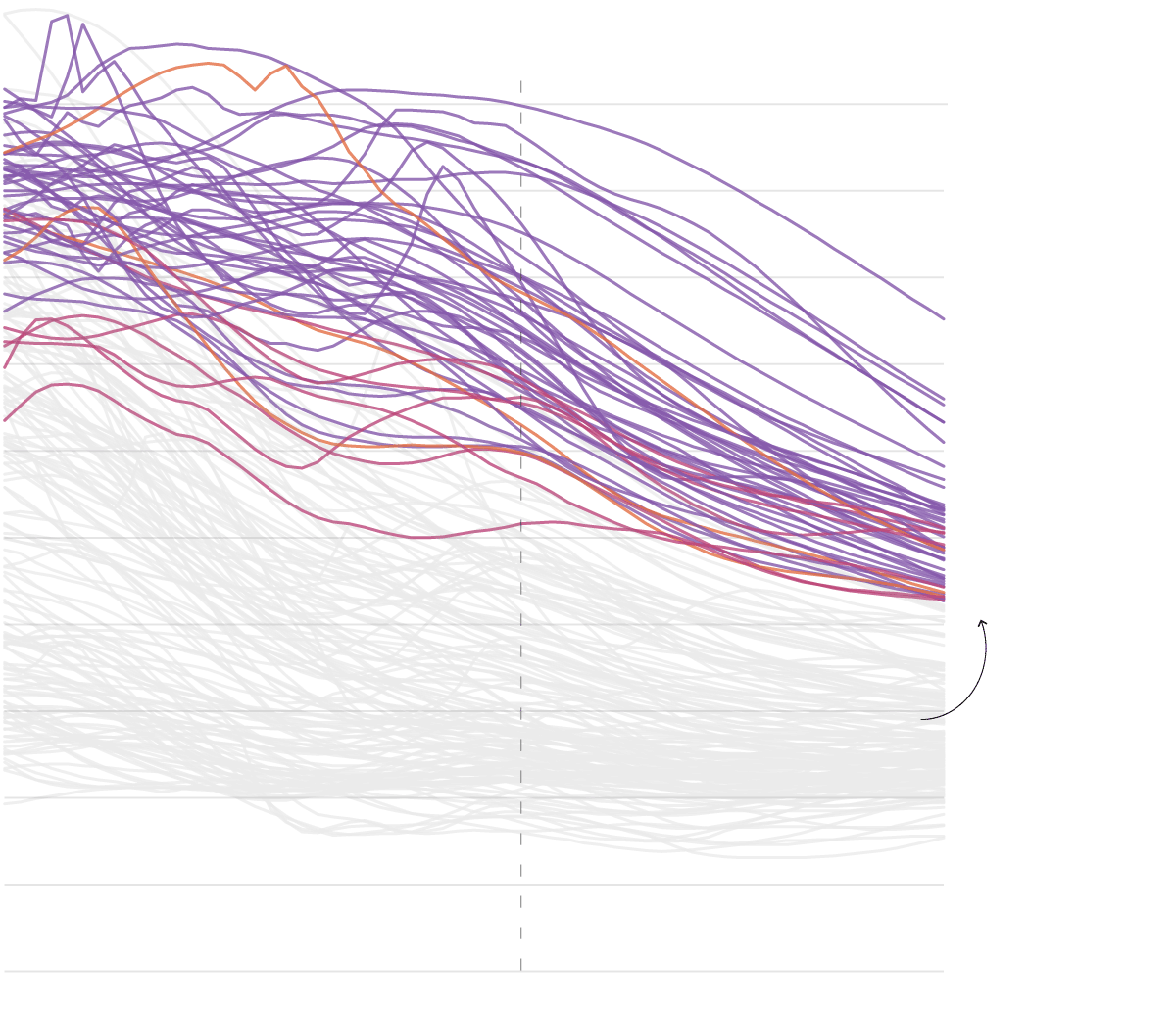

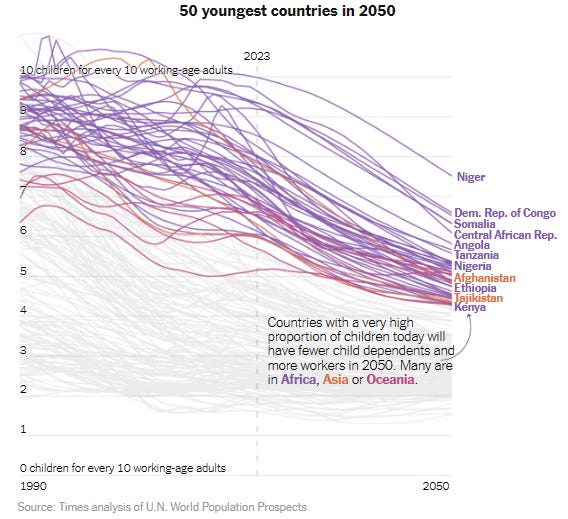

50 youngest countries in 2050

As in many young countries, birth rates in Kenya have declined drastically in recent years. Women had an average of eight children 50 years ago, but only just over three last year. Demographically, Kenya looks something like South Korea in the mid-1970s, as its economy was beginning a historic rise, although its birth rate is declining somewhat more slowly. Much of South Asia and Africa have similar age structures.

The upside is enormous.

A similar jump in the working-age population may explain about a third of the economic growth through the end of the last century in South Korea, China, Japan and Singapore, according to the best estimates — an enormous amount of economic growth.

Countries shown are those projected to have a population of 1 million or more by 2050, according to U.N. projections. Ages are shown as five-year averages. Regions are based on U.N. classifications.

Many of these demographic changes are already baked in: Most people who will be alive in 2050 have already been born.

But predictions always involve uncertainty, and there is evidence that sub-Saharan African countries’ fertility rates are dropping even faster than the U.N. projects — meaning that those African countries could be even better positioned in 2050 than currently expected.

But without the right policies, a huge working-age population can backfire rather than lead to economic growth. If large numbers of young adults don’t have access to jobs or education, widespread youth unemployment can even threaten stability as frustrated young people turn to criminal or armed groups for better opportunities.

“If you don’t have employment for those people who are entering the labor force, then it’s no guarantee that the demographic dividend is going to happen,” said Carolina Cardona, a health economist at Johns Hopkins University who works with the Demographic Dividend Initiative.

East Asian countries that hit the demographic sweet spot in the last few decades had particularly good institutions and policies in place to take advantage of that potential, said Philip O’Keefe, who directs the Aging Asia Research Hub at the ARC Center of Excellence in Population Aging Research and previously led reports on aging in East Asia and the Pacific at the World Bank. IF… and if war never happens, especially between China and Taiwan.

Other parts of the world – some of Latin America, for example – had age structures similar to those East Asian countries’ but haven’t seen anywhere near the same growth, according to Mr. O’Keefe. “Demography is the raw material,” he said. “The dividend is the interaction of the raw material and good policies.”

The Challenges of Aging

50 oldest countries in 2050

Today’s young countries aren’t the only ones at a critical juncture. The transformation of rich countries has only just begun. If these countries fail to prepare for a shrinking number of workers, they will face a gradual decline in well-being and economic power.

The number of working-age people in South Korea and Italy, two countries that will be among the world’s oldest, is projected to decrease by 13 million and 10 million by 2050, according to U.N. population projections. China is projected to have 200 million fewer residents of working age, a decrease higher than the entire population of most countries.

Large countries with the highest share of population 65 or older by 2050

To cope, experts say, aging rich countries will need to rethink pensions, immigration policies and what life in old age looks like.

Change will not come easy. More than a million people have taken to the streets in France to protest raising the retirement age to 64 from 62, highlighting the difficult politics of adjusting.

Immigration fears have fueled support for right-wing candidates across aging countries in the West and East Asia. Less 2 weeks ago, Dutch Government PM Mark Rutte toppled by farmer and right wing. 4 Days ago, ery ambitious Nature Resources Law by EU already decrease and or deleted (some points of) significant target, again, thanks to pushes by farmers and rightwing.

(Some deleted article from Nature Resources Law/Regulation by EU)

“Much of the challenges at the global level are questions of distribution,” Dr. Myrskylä said. “So some places have too many old people. Some places have too many young people. It would of course make enormous sense to open the borders much more. And at the same time we see that’s incredibly difficult with the increasing right-wing populist movements.”

The changes will be amplified in Asian countries, which are aging faster than other world regions, according to the World Bank. A change in age structure that took France more than 100 years and the United States more than 60 took many East and Southeast Asian countries just 20 years.

Not only are Asian countries aging much faster, but some are also becoming old before they become rich. While Japan, South Korea and Singapore have relatively income levels, China reached its peak working-age population at 20 percent the income level that the United States had at the same point. Vietnam reached the same peak at 14 percent the same level.

Pension systems in lower-income countries are less equipped to handle aging populations than those in richer countries.

In most lower-income countries, workers are not protected by a robust pension system, Mr. O’Keefe said. They rarely contribute a portion of their wages toward retirement plans, as in many wealthy countries.

“That clearly is not a situation that’s going to be sustainable socially in 20 years’ time when you have much higher shares of aged population,” he said. “Countries will have to sort out what model of a pension system they need to provide some kind of adequacy of financial support in an old age.”

And some rich countries won’t face as profound a change — including the United States.

Slightly higher fertility rates and more immigration mean the United States and Australia, for example, will be younger than most other rich countries in 2050. In both the United States and Australia, just under 24 percent of the population is projected to be 65 or older in 2050, according to U.N. projections — far higher than today, but lower than in most of Europe and East Asia, which will top 30 percent.

Aging is a tremendous achievement despite its problems.

“We’ve managed to increase the length of life,” Dr. Myrskylä said. “We have reduced premature mortality. We have reached a state in which having children is a choice that people make instead of somehow being coerced, forced by societal structures into having whatever number of children.”

People aren’t just living longer; they are also living healthier, more active lives. And aging countries’ high level of development means they will continue to enjoy prosperity for a long time.

But behavioral and governmental policy choices loom large.

The wishful thinking that dominates the worldview of Western green elites. They are determined to believe that there are quick and easy routes to decarbonising the economy. That it’s possible to meet people’s energy needs today without using fossil fuels or nuclear power. That the transition to clean, green energy is just around the corner, and the only thing standing in its way are the evil fossil-fuel companies.

This is a dangerous, infantile outlook. And it’s not just confined to the likes of groups like Just Stop Oil. It is the outlook of a large part of our political and media elites, too. They talk up the transition to clean energy and set grandstanding Net Zero targets. And they encourage the demonisation and cessation of fossil-fuel use. But all their green schemes will come at a huge human cost.

The truth is that our societies are still massively dependent on fossil fuels. For all the talk of the advances made in renewable energy, the proportion of our electricity production reliant on fossil fuels has barely changed over the past 40 years. In that time, only nuclear power has declined as a source of electricity.

None of this is to say that an energy transition is impossible. A target of Net Zero by 2050 could well be met. But the rapid abandonment of fossil fuels that this demands would inflict misery and hardship on billions of people.

Turbines of the Burbo Bank offshore wind farm in the mouth of the River Mersey in Liverpool, England.

How fossil fuels power the world

Of course, Western elites will claim that the energy transition is absolutely necessary if we’re to avert catastrophe from climate change. King Charles III and London mayor Sadiq Khan even unveiled a ‘National Climate Clock’ last month, just to show how little time we supposedly have left to stave off the apocalypse.

In truth, Western politicians themselves don’t really take their own doom-mongering that seriously. They know that talk of ending fossil fuels appeals to parts of the electorate. Plus it looks good on the global stage. It’s something to posture over at the annual COP junket. But they also know that most people would be unwilling to bear the consequences of an actual end to fossil fuels.

US president Joe Biden, for example, is well aware that gasoline prices have a direct impact on his re-election prospects. This is why he has shown no hesitation in draining America’s Strategic Petroleum Reserve to keep prices down.

The same bad faith is at work among European politicians, too. They hype up the ‘climate emergency’ and posture over Net Zero targets. But when push comes to shove, they relent. Germany, for example, likes to present itself as a leader of the global energy transition. Yet as soon as the energy crisis started to bite last year, the German government brought coal power plants back online to power the electricity grid. And it did so by burning lignite, the dirtiest type of coal.

Then there’s Norway, the fifth-richest country in the world, which is blessed with abundant natural resources and hydropower. It has become the poster child for the introduction of electric vehicles, and we’re told it is showing the world how to manage the energy transition. But is it really? Domestic oil consumption in Norway today is about as high as it was in 1985. Despite the hype, Norway’s energy transition is going much slower than the headlines let on. Norwegians themselves know which side their Smørrebrød is buttered. Indeed, Oslo has just approved $18 billion in funding to help develop another 19 oil and gas fields.

Western governments’ green hypocrisy is revealing. They posture endlessly about Net Zero and indulge in fantasies about the energy transition. Yet they can’t escape the fact that fossil fuels are integral to their societies’ wellbeing.

Canadian political scientist Vaclav Smil lists cement, steel, plastics and ammonia as the four ingredients that make the modern world possible. For example, modern healthcare systems need enormous amounts of plastic (for everything from flexible tubes to sterile packing), making it yet another crucial ingredient in the wellbeing of humanity. And without steel and cement, nothing could be built – no roads, no houses, no harbours, no airports. Plastics, steel and cement also require fossil fuels for their production.

The same goes for modern agriculture. It depends on synthetic fertilisers, which massively increase yields and allow farmers to use smaller areas of arable land. Without these fertilisers, half the current global population would go unfed.

The production of these fertilisers depends on something called the Haber-Bosch process, a method of producing ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen, which was invented in the early 20th century. Given its contribution to feeding the world, Smil has justifiably called it the ‘most momentous technical advance in history’.

The problem for those demanding the phasing out of fossil fuels is that the hydrogen required for the production of ammonia, and therefore synthetic fertilisers, is almost entirely derived from fossil fuels. So all of Smil’s building blocks for the modern world are dependent on the very materials that Western elites say they want to keep in the ground.

It’s not just fertilisers that require fossil fuels, either. Seventy-five per cent of all farm equipment in the US runs on diesel. It dominates the entire farming supply chain, from planting to harvesting to bringing food to market.

A green optimist might suggest simply replacing all these diesel-powered machines with industrial EVs. Yet to build the batteries for all these EVs would require a massive expansion of energy-intensive mining for metallic minerals, such as cobalt, lithium, manganese and nickel. EVs would also require clean electricity sources to charge them.

In fact, every step of the proposed energy transition is itself dependent on fossil fuels. You cannot build a wind turbine without lubricants from oil, a concrete foundation and copious amounts of steel. Just as you cannot make solar panels without polysilicon, a component that is immensely energy intensive to produce because it requires temperatures beyond 1,150 degrees Celsius.

The expansion of mining activities needed to build EVs and wind turbines is particularly problematic for the clean-tech crusaders. According to the International Energy Agency:

‘A typical electric car requires six times the mineral inputs of a conventional car and an onshore wind plant requires nine times more mineral resources than a gas-fired plant. Since 2010, the average amount of minerals needed for a new unit of power generation capacity has increased by 50 per cent as the share of renewables in new investment has risen.’

The mineral-mining sector is also energy intensive, producing a huge amount of carbon emissions. It is already responsible for 38 per cent of total global industrial energy use. This means that even if the electrification of all vehicles were possible, it wouldn’t eliminate carbon emissions. It would just raise them at other points in the supply chain.

Moreover, the environmental movement already wants to clamp down on mineral mining. Mining permits in Europe and the US have already been restricted. This means that the minerals for the production of EVs and wind turbines will likely come from poor nations with fewer restrictions on mining and with atrocious labour conditions. We can already see this happening in the cobalt mines of the Congo.

Young boys play at the bottom of a cracked, dried reservoir in western Guangdong Province, southern China.

Western nations have long enjoyed the benefits of industrialisation. Now, by clamping down on fossil fuels, they are trying to pull up the ladder. German foreign secretary Annalena Baerbock even had the audacity to lecture South Africa on its use of coal recently, while her own government has been burning it at record rates. Not without reason, parts of the developing world are beginning to accuse the West of engaging in ‘green colonialism’.

Make no mistake, the West’s prosperity rests on fossil fuels. The Industrial Revolution was fuelled by the exponential growth in available energy. In 1870, British steam engines generated four million horsepower, the equivalent amount of work done by 40million men. Feeding such a workforce would have required three times Britain’s entire wheat output. But in 1870, all it took to generate one horsepower was a pound of coal.

Coal was just the beginning. Soon oil was added to the fuel mix and eventually gas, too. This massive increase in energy production allowed a tremendous increase in living standards. The average Briton in 1960 was six times richer than his great grandfather in 1860.

Industrialisation transforms societies. The industrialisation of agriculture, for example, enables higher outputs with less labour, freeing humans for other endeavours. In the US, the labour needed to produce a kilogram of grain fell by 98 per cent between 1800 and 2020. The share of the population working in agriculture fell by a similar margin during that period. Not every country will have to follow this development path exactly – coal, for example, could be replaced by gas and nuclear. But what is certain is that no country will be able to industrialise and develop without fossil fuels.

The developing world needs what the West already has. It needs roads, railways, housing, transmission lines and factories. In many parts of the globe, such infrastructure is all but nonexistent. Around 940million people (13 per cent of the global population) do not have access to electricity; and three billion people are forced to cook with dung, wood or other solid fuels – all of which create health risks due to indoor air pollution.

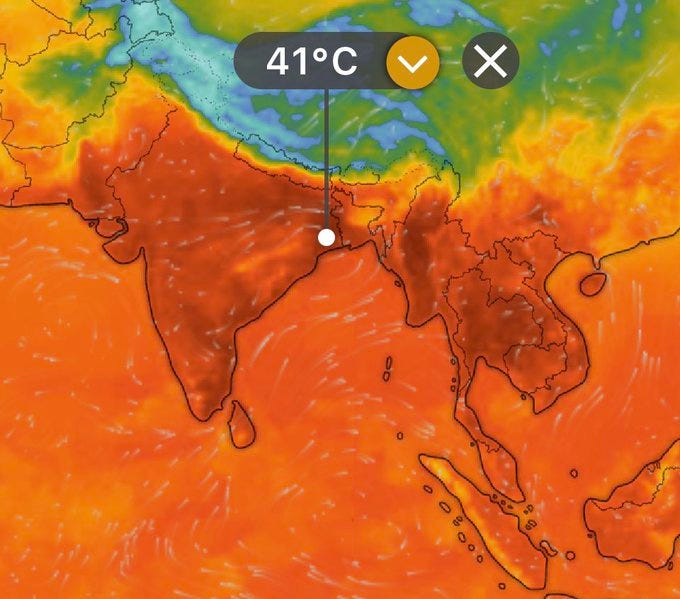

These parts of the world need the elements of modern life that are taken for granted in the industrialised world. If we are really worried about heat waves in India, we should support the production and dissemination of air conditioning. And if we want to increase life expectancy in Sub-Saharan Africa, we should expand access to electricity and natural gas so that people no longer need to burn dung. All of these steps will call for the use of fossil fuels. Denying them to the poorest on the planet would condemn billions to shorter life expectancies, worse health conditions and higher child mortality.

The talk of leaving fossil fuels behind is not based in reality. It’s fuelled instead by a mixture of apocalypticism, hypocrisy and sheer wishful thinking. In the future, perhaps we will be able to power hospitals using kinetic energy. But right now, the costs of abandoning fossil fuels will likely do far more harm than climate change itself.

“You can say with some kind of degree of confidence what the demographics will look like,” Mr. O’Keefe said. “What the society will look like depends enormously on policy choices and behavioral change.”

==========END————

Thank you, as always, for reading. If you have anything like a spark file, or master thought list (spark file sounds so much cooler), let me know how you use it in the comments below.

If you enjoyed this post, please share it.

If a friend sent this to you, you could subscribe here 👇. All content is free, and paid subscriptions are voluntary.

————

-prada- Adi Mulia Pradana is a Helper. Former adviser (President Indonesia) Jokowi for mapping 2-times election. I used to get paid to catch all these blunders—now I do it for free. Trying to work out what's going on, what happens next. Arch enemies of the tobacco industry, (still) survive after getting doxed. Now figure out, or, prevent catastrophic situations in the Indonesian administration from outside the government. After his mom was nearly killed by a syndicate, now I do it (catch all these blunders, especially blunders by an asshole syndicates) for free.

(Very rare compliment and initiative pledge. Thank you. Yes, even a lot of people associated me PRAVDA, not part of MIUCCIA PRADA. I’m literally asshole on debate, since in college). Especially after heated between Putin and Prigozhin. My note-live blog about Russia - Ukraine already click-read 4 millions.

=======

Thanks for reading Prada’s Newsletter. I was lured, inspired by someone writer, his post in LinkedIn months ago, “Currently after a routine daily writing newsletter in the last 10 years, my subscriber reaches 100,000. Maybe one of my subscribers is your boss.” After I get followed / subscribed by (literally) prominent AI and prominent Chief Product and Technology of mammoth global media (both: Sir, thank you so much), I try crafting more / better writing.

To get the ones who really appreciate your writing, and now prominent people appreciate my writing, priceless feeling. Prada ungated/no paywall every notes-but thank you for anyone open initiative pledge to me.

(Promoting to more engage in Substack) Seamless to listen to your favorite podcasts on Substack. You can buy a better headset to listen to a podcast here (GST DE352306207).

Listeners on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Overcast, or Pocket Casts simultaneously. podcasting can transform more of a conversation. Invite listeners to weigh in on episodes directly with you and with each other through discussion threads. At Substack, the process is to build with writers. Podcasts are an amazing feature of the Substack. I wish it had a feature to read the words we have written down without us having to do the speaking. Thanks for reading Prada’s Newsletter.

Headset and Mic can buy in here, but not including this cat, laptop, and couch / sofa.